Which is a better investment: Property or shares?

In this wire, Andreas Lundberg Senior Analyst at Montgomery Investment Management, tackles the question of how an investment property would measure up if analysed using an equity analysis framework:

"To start off, I would like to point out a fundamental difference between a company and an (existing) investment property:

- A company generating excess operating cashflow above the cost of servicing its debt and the cost of replacing the assets that does not have an infinite life has the choice whether to pay out a dividend now and provide its investors a direct return on their investment or to reinvest the excess cash into the business and eventually pay its shareholders a higher dividend. If the incremental return on such investments is in excess of the cost of equity for the company, shareholders should be supportive of the company doing so as the additional amount of cash they will receive at a later date is high enough for them to forgo the immediate receipt of a smaller amount of cash (i.e. the discounted value of future cash receipts is higher than the current value of the cash).

- Conversely, for an existing investment property, there is not much reinvestment that can significantly increase the value of the property directly (a renovation like a new kitchen or bathroom should in my mind be compared to maintenance capex for a company). The reason for this is that a property is not a productive entity in the sense that it does not take an input, adds value to it and then sells it for a higher price that reflects the value added and is hence not able to deploy incremental capital in the same way as a business, but is a stable asset providing a basic need that does not change over time (shelter).

- What an investment property provides is instead an income stream in terms of the rent it can generate plus any potential change in its value which is driven by investors’ increasing appetite for income and/or their anticipation that someone else will be prepared to buy the asset from them in the future for a higher price than they paid (greater fool theory).

From this follows that an investment property should really be looked more at through the lens of a fixed income security (an inflation fixed income security adjusted as rents can increase over time to reflect the overall price levels in the economy) but with an overlay of the potential for capital gains if either external conditions change that makethe asset more attractive (e.g. interest rate reduction or lack of alternative investments etc.).

For simplicity, lets compare an investment in an investment property to buying an index fund investing in the S&P500 (the available data for S&P500 is much longer than for ASX but the principle is the same).

THE SCENARIO

The scenario I have assumed is that you are investing on a 10-year horizon and that you need to access the capital at the end of the period for some reason (i.e. fund your children’s education, buy a nice boat to sail the world etc).

EXPECTED RETURN FOR A FUND INVESTMENT

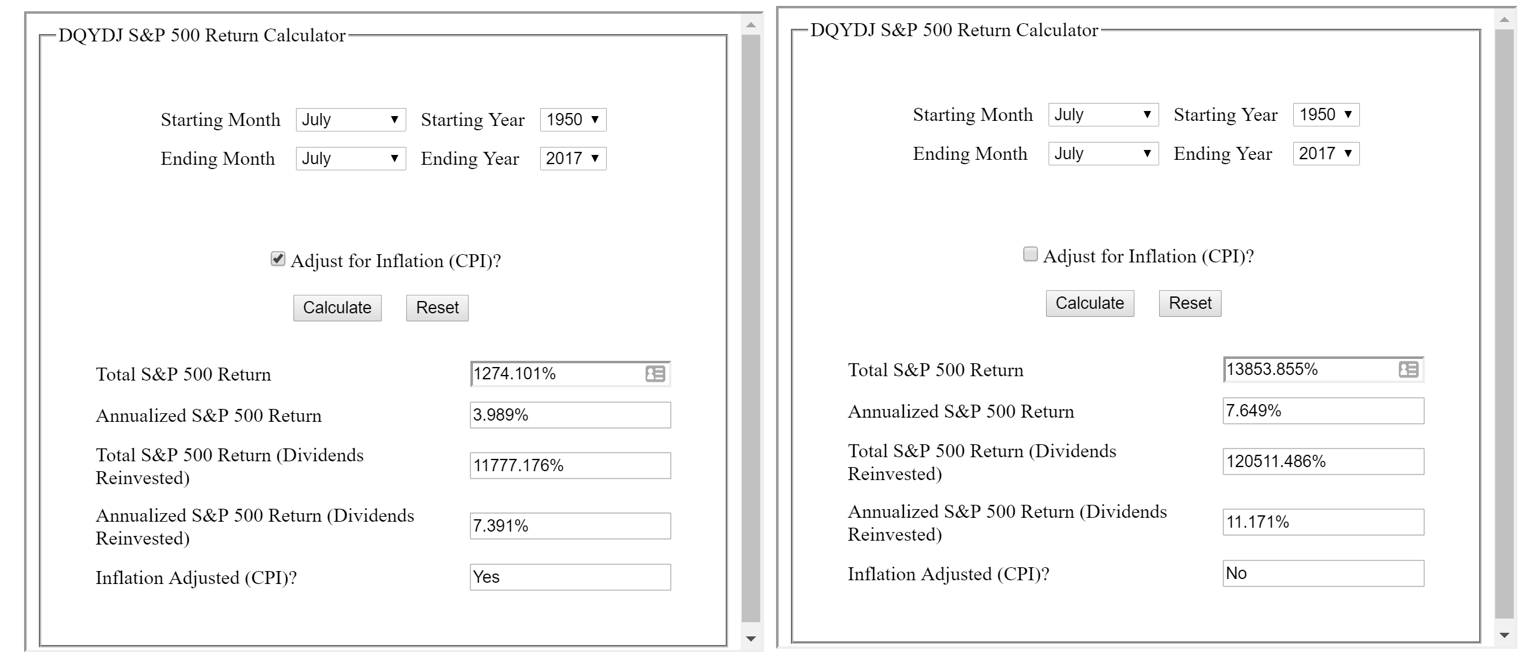

Over a long time (say since 1950 to take away the effects of WW2), the S&P500 accumulation index (which assumes reinvestment of dividends) has returned 7.4% adjusted for inflation and 11.2% if we do not adjust for inflation.

On top of this, we have to adjust for fees as an individual investor most likely cannot replicate the S&P500 by himself due to not having enough money to invest in all the companies included in the index; but for this analysis, let’s assume that you are able to, by picking a fund which slightly outperforms the index to compensate for fees, so the net expected return going forward is equal to the gross returns.

Now, during this period we have had interest rates on average falling significantly making stocks more attractive than bonds and this will not be repeated going forward (as interest rates are already close to zero in many places) so we should most likely not expect that the future will be as strong as history but let’s say that we should probably expect to, over the long term, make a nominal return of about 9% per year (i.e. including inflation) from investing in the stock market.

A special feature of investing in the stock market is that there are virtually no transaction costs apart from capital gains tax when you exit your investment, which, in Australia, depends on your overall income. Assume that you have a 30% marginal tax rate (which we will assume for the rest of this example) and the post-tax return you can expect over time from investing in the stock market is near 6.3% per year.

EXPECTED RETURN FOR AN INVESTMENT PROPERTY

The expected return for an investment property is a bit more complicated to calculate but let’s give it a try! Let’s start by dividing the return into two parts:

- Yield – the direct return you get from owning the property

- Capital gain – The potential gain you get if the price of the property increases by the time you sell it.

Let’s start with yield:

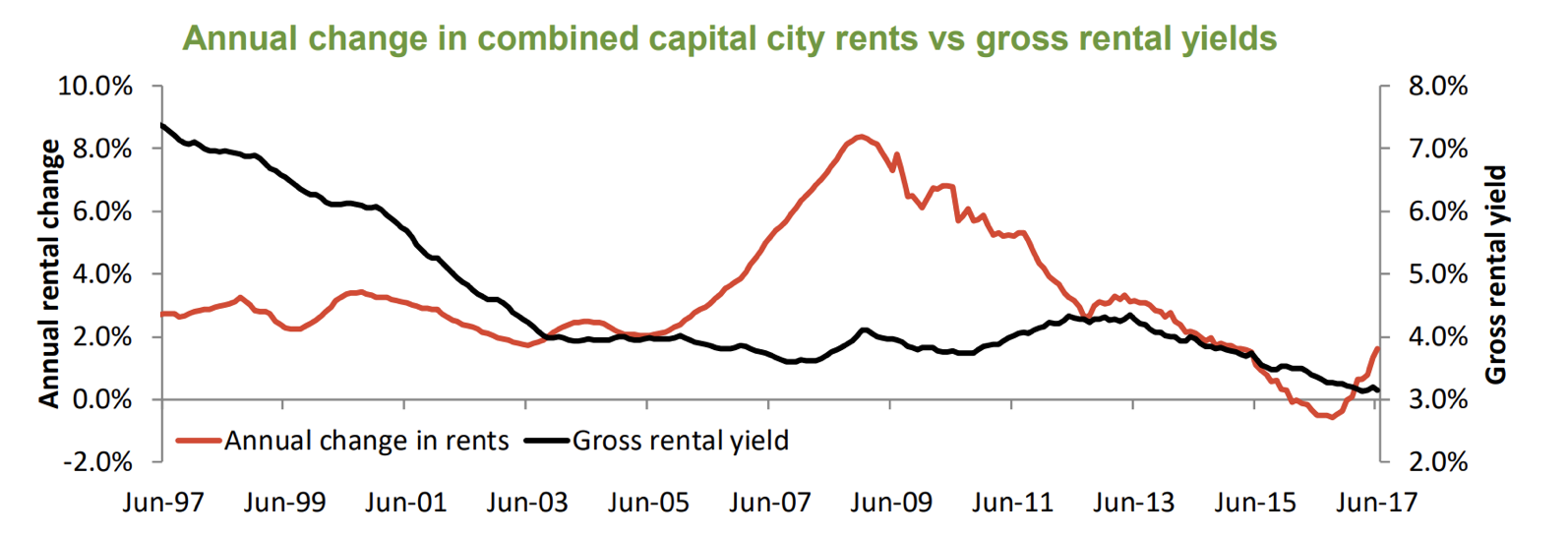

Gross rental yield is currently (according to Corelogics property monitor), on average across the combined capital cities in Australia 3.1% and is current growing by about 1.5% per year but for this example I am going to assume that rent grows in line with overall inflation that I assume will be 2.0% per year.

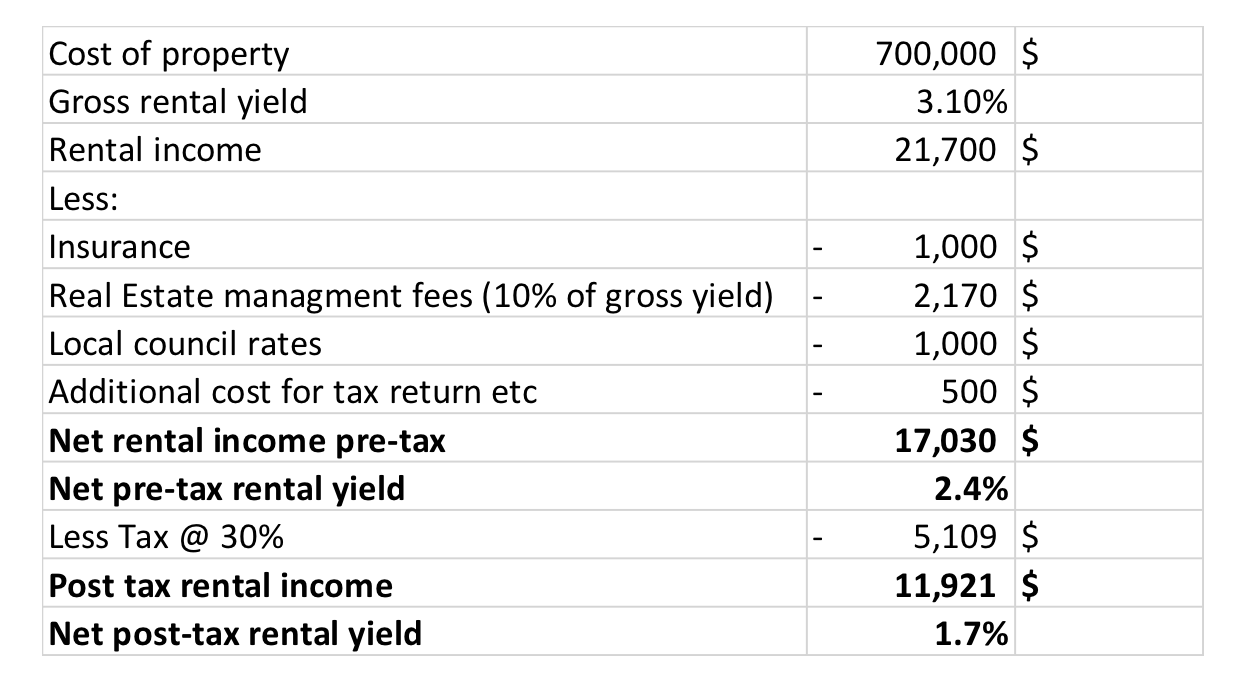

We do need to take away several costs associated with owning the property (assume we buy a property valued at $700,000):

- Insurance – You are not going to let this expensive property be uninsured so let’s assume $1,000 per year.

- Real estate management fees – Generally about 10% of the rental income

- Local council rates – Water and sewerage etc. Assume $1,000 per year

- Additional cost for tax return – Your tax return is suddenly much more complicated and your accountant will likely charge you more to prepare the tax return (or see it as an opportunity cost on your own time). Let’s assume $500 per year.

- Tax – As per above, we assume that your marginal tax rate is 30% and that the rental income is taxed at that rate.

Your net rental yield on a $700,000 property is therefore about 2.4% or ~$17,000 per year which we can grow with inflation (which we have assumed is 2.0%):

Capital gains

In addition, you’ll have a few one-off transaction costs associated with buying and selling the investment property:

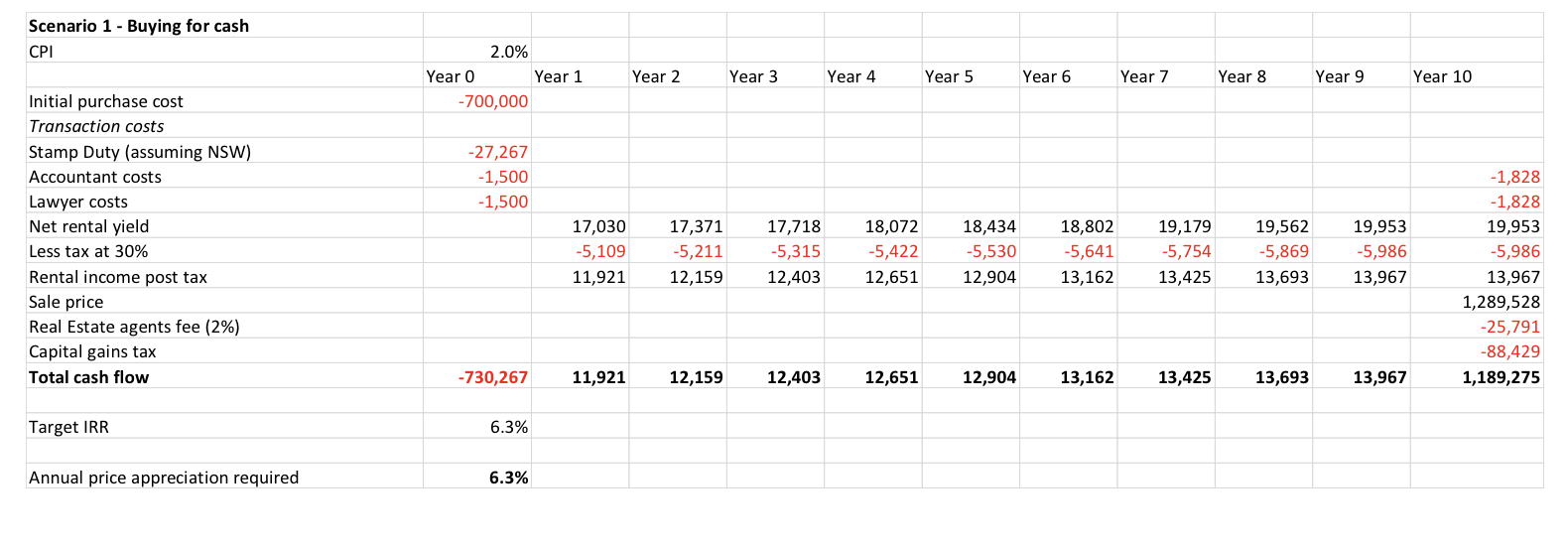

- Stamp duty – Assuming that the investment property is in NSW (it would be much higher in VIC and slightly cheaper in QLD), the stamp duty for a $700,000 property would be about $27,000 and this is payable at the purchase of the property.

- Agent commission – This is ~2% of the transaction and the seller pays this so for our purposes, we apply this at the end of the 10-year period.

- Other transaction costs – You will likely have some accountant and lawyer costs associated with the transaction which I have assumed will be $3,000 in total both on the way in and on the way out (the cost when selling has been adjusted for inflation as it is 10 years into the future).

- Capital gains tax – I have assumed that the current 50% discount on CGT is still in place by the end of the 10-year period despite the current political talks about removing it.

In the tables below, I have for two different scenarios looked at what level of nominal (i.e. including inflation) annual price appreciation would be needed to match the 6.3% post-tax return that we assume a long-term investment in the equity market should give you (technically, we are solving the annual price appreciation that gives us an internal rate of return (IRR) of 6.3% over the 10-year period). The scenarios are:

- You buy the property for cash.

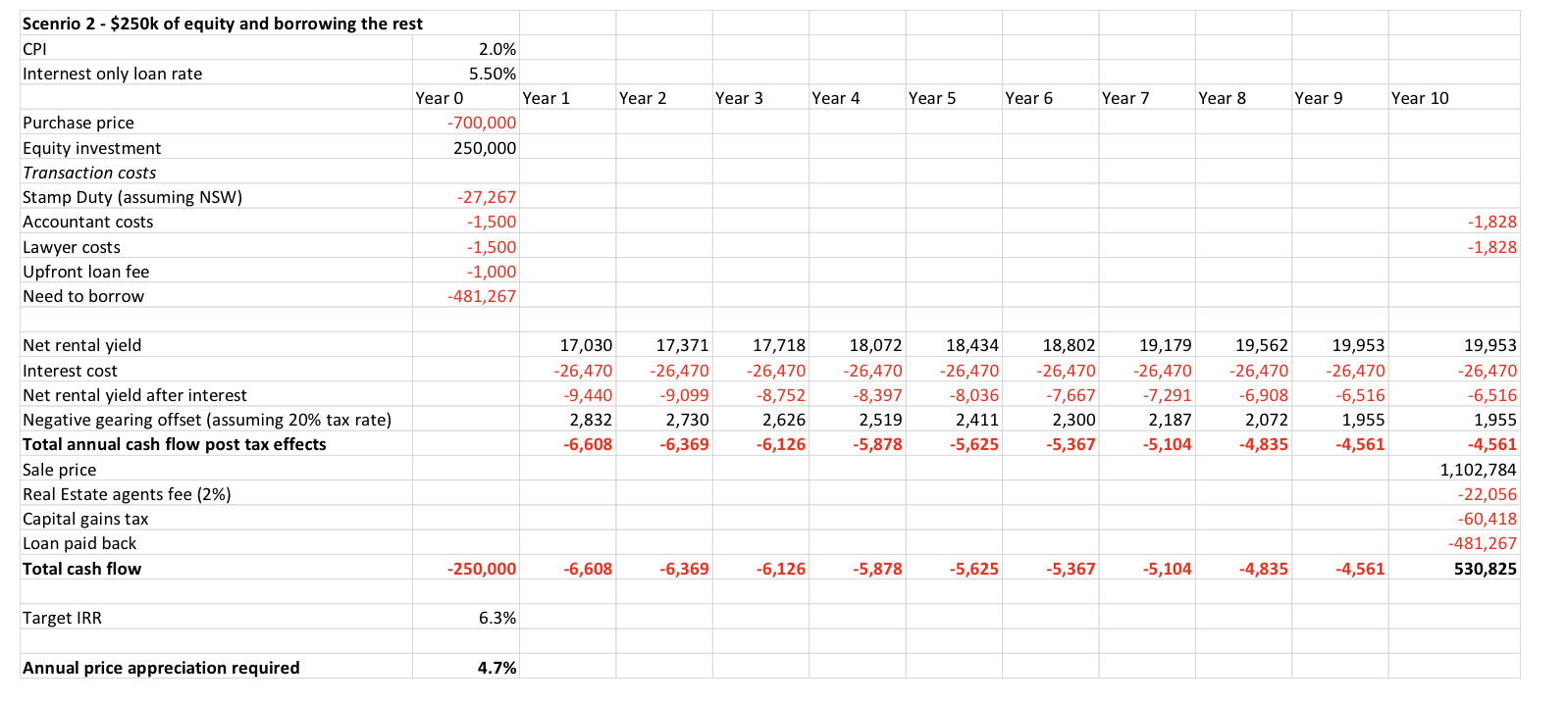

- You invest $250,000 of equity and borrow the rest:

a. We assume a non-amortising loan (interest only) variable interest loan with an interest rate of 5.5%.

b. We also assume that there are $1,000 of set-up fees for the bank loan.

c. We also assume that you have a constant tax marginal rate of 30% during the 10 years for the purposes of negative gearing offset as with a pre-tax net rental yield of 2.4% and borrowing costs of 5.5%, you are clearly going to be experiencing ongoing negative cashflow.

Scenario 1

As can be seen from the table below, we need to assume an annual price appreciation of 6.3% per year to achieve a post-tax IRR of 6.3%.

Scenario 2

Thanks to the leverage effect, the required annual price appreciation needed to achieve a 6.3% post tax IRR is a little bit lower than in scenario 1 at 4.7%. We should though remember that due to the leverage we have taken on, our investment hurdle rate should be much higher due to the additional risk we are taking on (remember that you have a subordinated interest in the property, the bank has the first priority and will outrank you in case the value goes down and if you wanted a higher expected return from an investment in equity markets, you could gear your investment there through a margin loan) but for this analysis we are ignoring that.

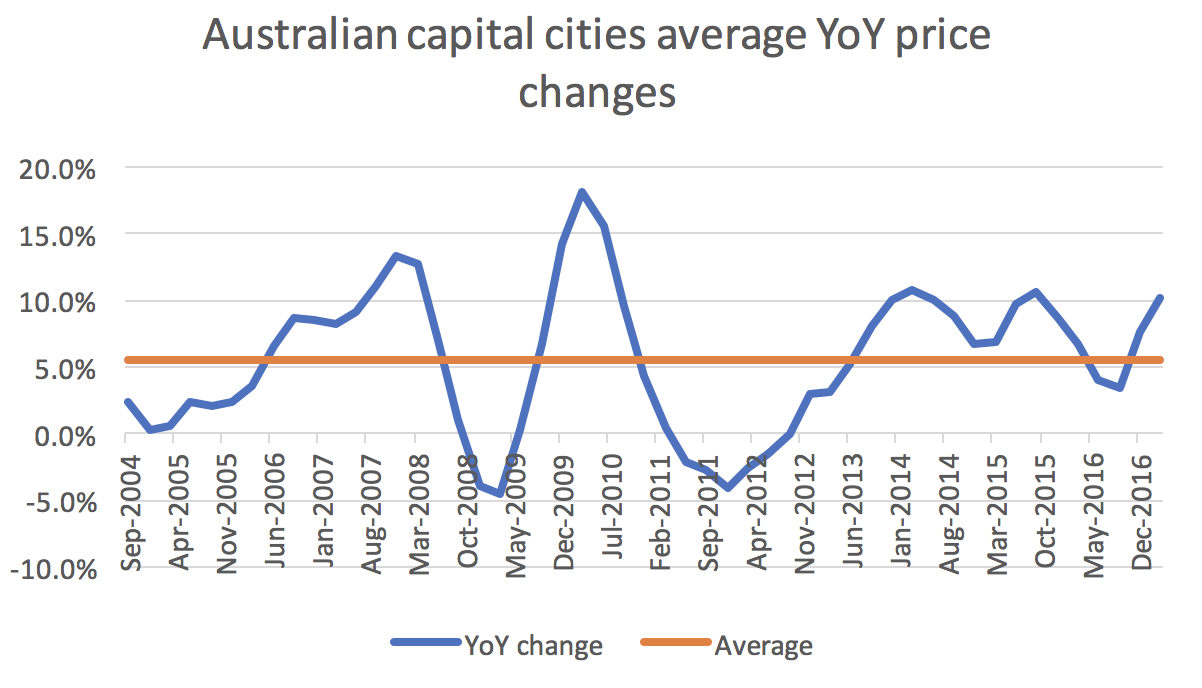

Looking at historical price appreciation of property in Australia for the last 13 years (this is the length of the data ABS supplies) we can see that the average has been 5.5% which means that you would have underperformed the expected returns from investing in the S&P500 if you had bought the property for cash and only slightly outperformed an ungeared stock market investment by taking on a lot of leverage.

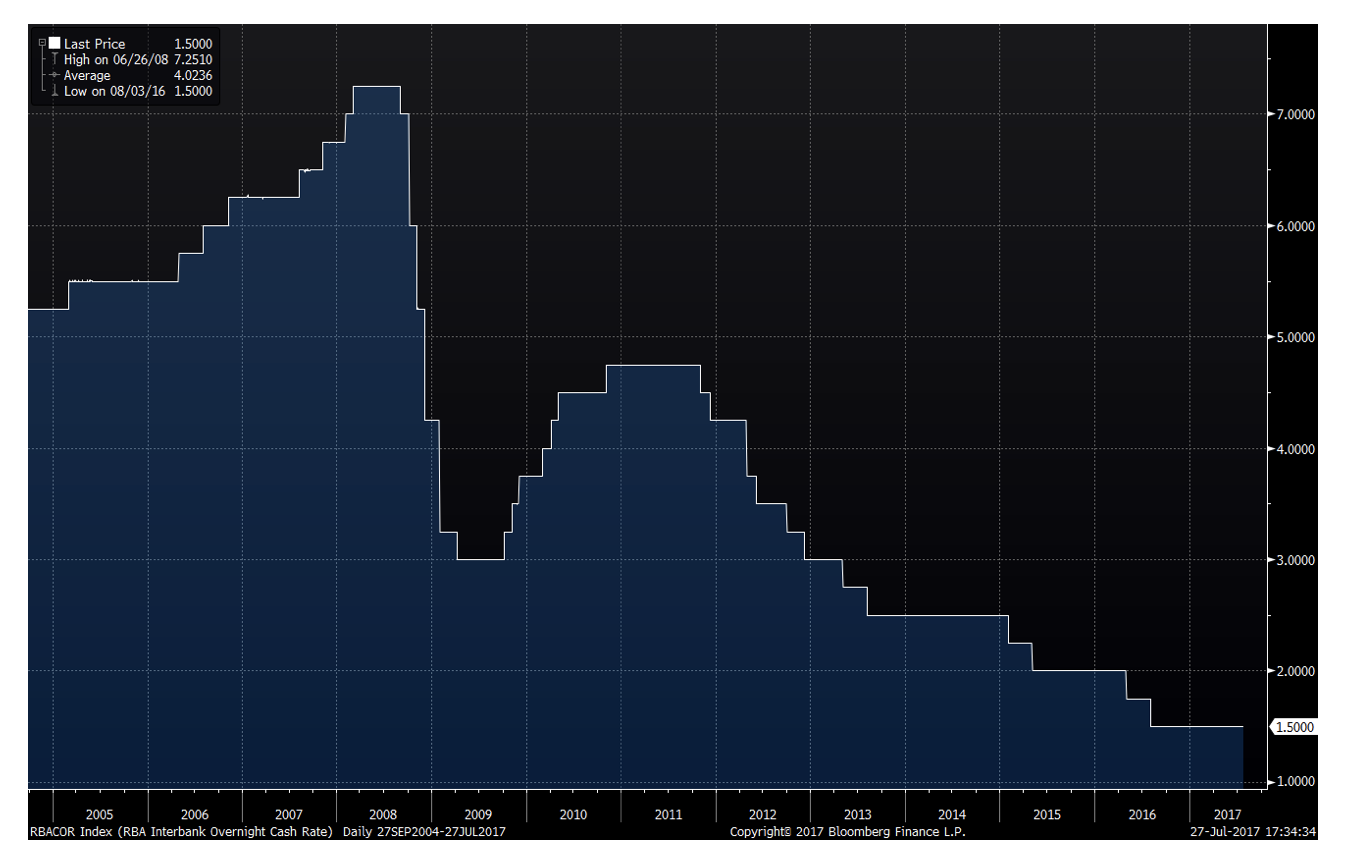

We should though note that during this period, the cash interest rates in Australia declined from 5.2% to 1.5%, increasing the affordability of borrowing…

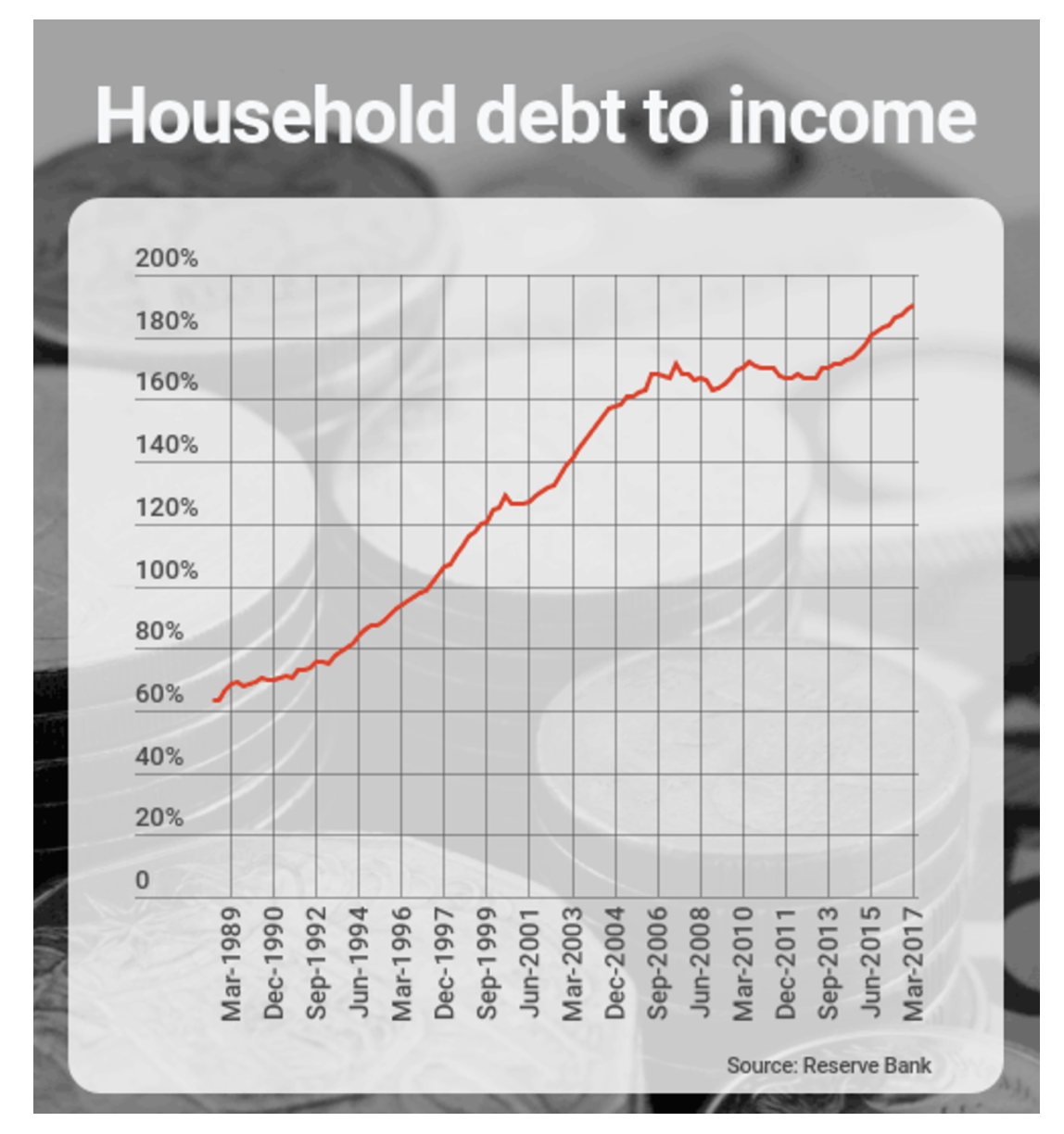

and that households have responded to this and taken on significant amounts of debt, resulting in the average debt to income ratio increasing from roughly 125% in 2004 to 190% currently which is one of the highest levels in the world.

CONCLUSION

It seems that during the last 13 years, investing in Australian property has produced a return that is slightly less than the expected return from investing in the S&P 500 over the long term (unless you significantly geared your property investment). We should though note the fundamentals for property prices have been extraordinary during this period with falling interest rates and easy access to credit through very expansionary policies by central banks. Property is, by its very nature of providing an easily accessible security to the lender, the easiest way that a “mum and dad” investor can get access to leverage and it seems like Australian investors have taken full advantage of this.

If we, during a period of unprecedented interest falls and domestic debt expansion have not been able to match the long term expected equity return by investing in the property market (on an ungeared basis), we would not expect the relative attraction of investment properties to increase in a rising interest rate environment which we are likely to see over the coming years. If banks are actually forced to reduce the growth in lending due to tightening money supply by central banks, it is very hard to see property prices increasing and, as direct rental yields are very low, returns from an investment in an investment property are likely to be very low going forward.

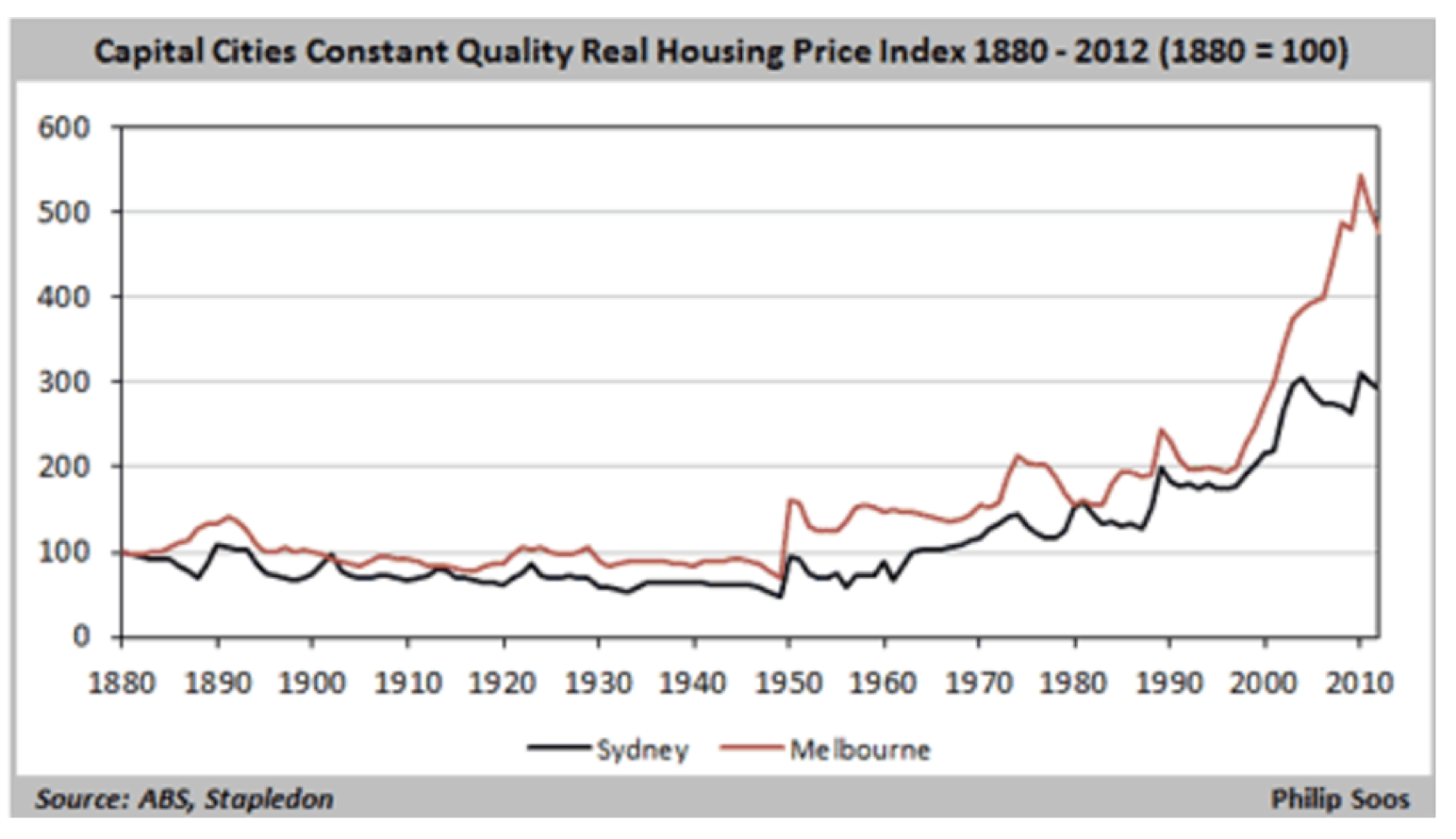

After all it is not a law of nature that property prices always go up even though that has been the case for the majority of time that anyone in Australia below the age of 47 has seen in their working life. If we look at a very long-term chart of Australian property prices, we can see that there have been several occasions of property prices going down by significant amounts. Most notably after the crash in 1896 when it took about 60 years before property prices recovered to their previous levels in real terms…

Please note that we are not arguing that investing in the S&P500 over the coming years will produce a much better return as we are likely to see a low return environment overall once central banks start to tighten credit policies (see Stuart Jackson’s blog post).

At Montgomery, we are at the moment defensibly positioned with a large cash position in reserve to take advantage of opportunities that the market presents over the coming months/years and we also offer a market neutral equities product domestically and a long/short equities product internationally.

Please note that we are not arguing that an investment property necessarily doesn’t make sense for some people as part of a diversified portfolio of investments or if you have particular needs (for example you want to buy an apartment your kids can use in the future etc.). What we are saying is that we see a high risk that the potential returns from an investment property in the future will be significantly below what they have been in the recent past.

Please also note that the above analysis is a bit simplified as it disregards potential depreciation tax benefits that might be available with an investment property investment but also disregards that it might be possible to get a higher expected return from an equities investment if you are willing to take on slightly higher risk by having part of your portfolio in, for example, an emerging markets fund.

If you would like to read more article by Andreas please click here.

Andreas is a Senior Analyst at Montgomery Investment Management. Andreas joined from Navigo Partners, a M&A advisory firm in Stockholm, Sweden where he was a Director responsible for origination and execution of Scandinavian projects. Before this, he worked for three years in corporate strategy at Alinta Energy in Sydney.

1 topic