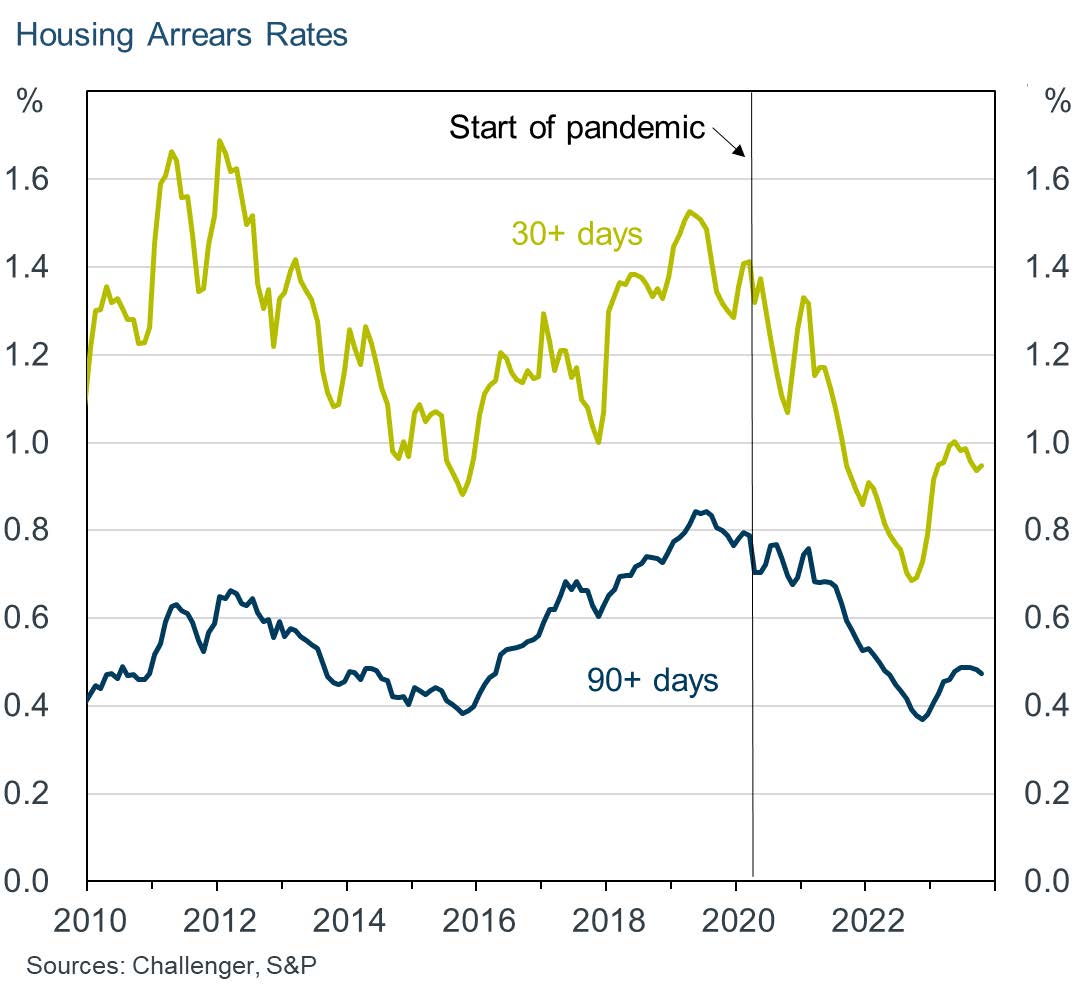

Why didn’t housing arrears increase in the pandemic?

Is the lesson we take away that housing arrears won’t increase even in a recession?

Two factors stand out in driving declining arrears: the widespread provision of repayment holidays and the substantial fiscal support which specifically boosted the incomes of households.

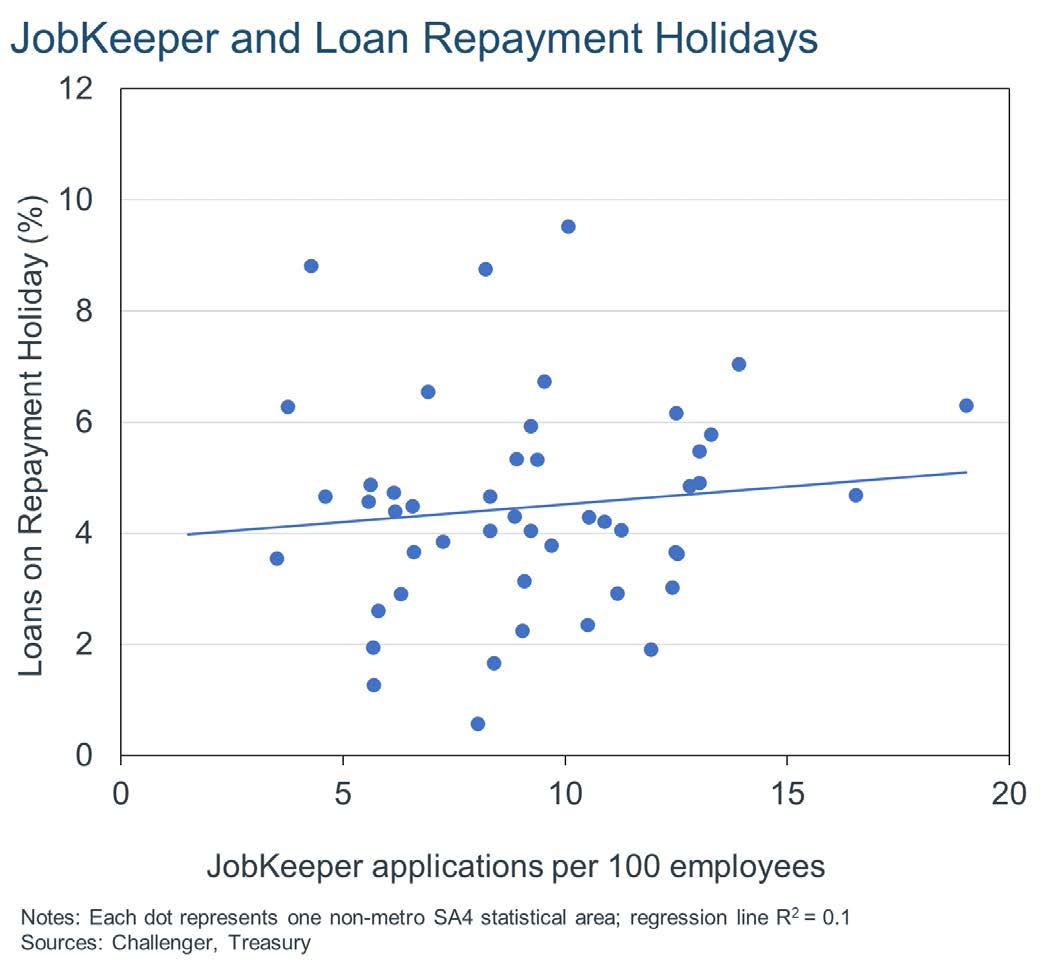

- Repayment holidays enabled borrowers to suspend their mortgage payments (principal and interest)without penalty for around 3 months if their loan was not already in arrears. While around 15% of borrowerstook out repayment holidays, for many this was precautionary and they subsequently made voluntarymortgage payments. In fact, there isn’t much of a relationship by the regions that experienced a largereconomic shock (as shown by a larger take-up of JobKeeper) and those with more repayment holidays (Figure 2). Not surprisingly more self-employed and investor borrowers took out repayment holidays.

- Two major parts of the fiscal stimulus benefited the types of households with mortgages.

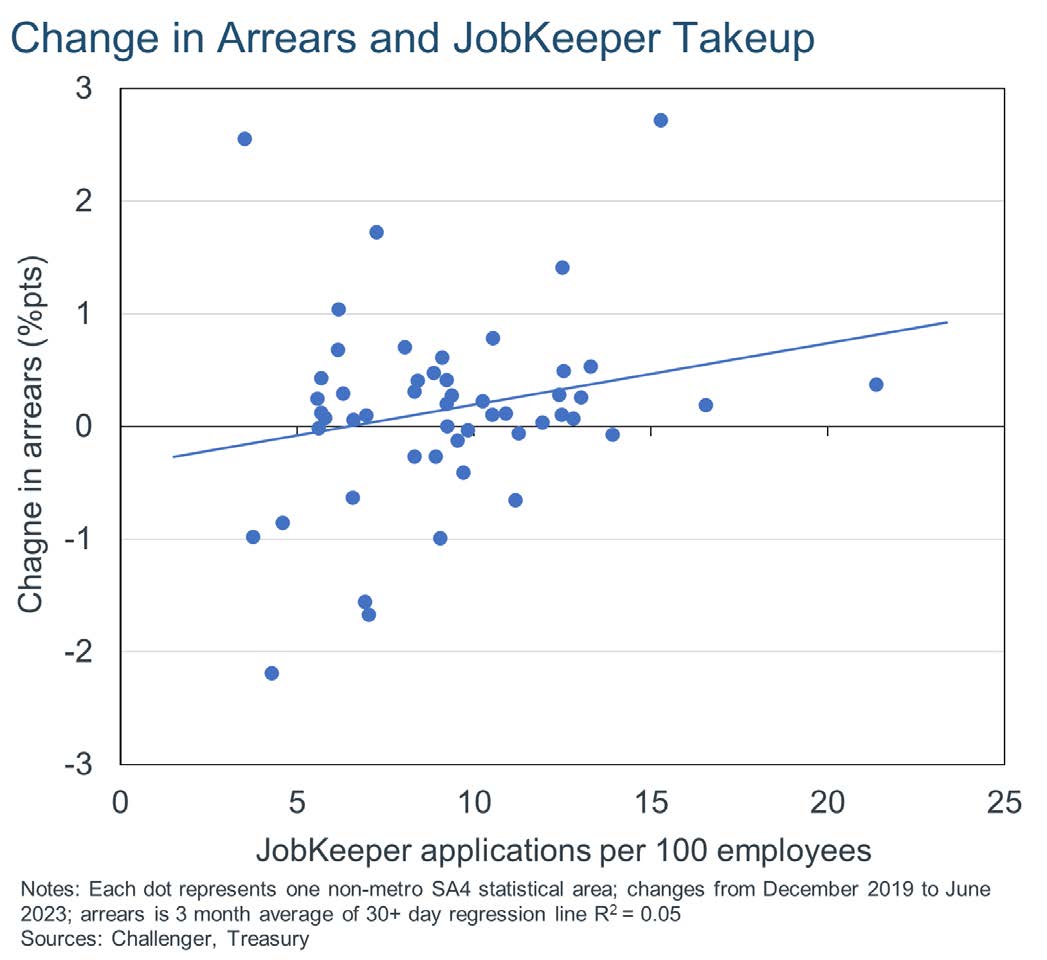

- JobKeeper ($88 billion, 6.6% of household disposable income) substituted for the wages of thosewhose work was impacted by the pandemic, income with which they could make mortgagepayments. Indeed, over half of households reported using JobKeeper payments to pay theirmortgage or rent. There isn’t much of a relationship between the regions that experienced a largereconomic shock (and so had larger JobKeeper take-up) and those with a larger increase in arrearsafter the pandemic, presumably because the stimulus helped to cushion the economic blow (Figure 3).

- Allowing lump-sum withdrawals from private superannuation ($38 billion, 2.8% of householddisposable income) of up to $20,000 also likely contributed as households with a mortgage tend tobe old enough to have built up at least some super. We don’t have precise data to link superwithdrawals to mortgage payments, but just under half of payments went to people aged 36-55, thecohort that owes most mortgage debt, so the circumstantial evidence is strong.

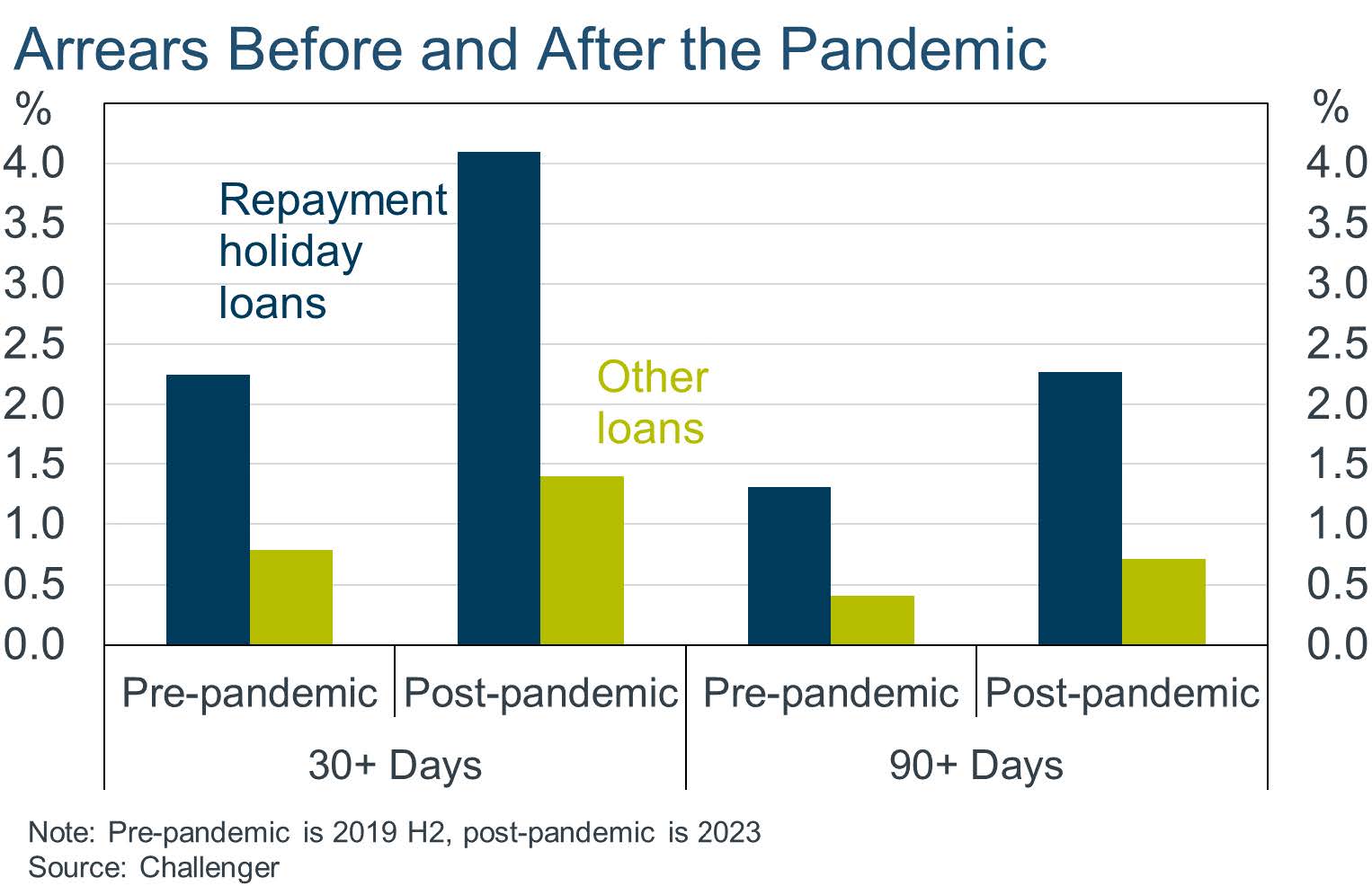

One interesting element is that it was mostly at the borrower’s discretion to take out a repayment holiday, and most did so early in the pandemic before they knew for sure the financial cost it would impose on them. In some ways, taking a repayment holiday may highlight those borrowers who were most concerned about their own financial position. There’s some evidence for this in that loans that took a repayment holiday had higher arrears both before and after the pandemic (Figure 4).

But we should not assume arrears will never increase. The pandemic was special, in that a health crisis was seen as a terrible and random event and so there was strong willingness by governments and lenders to help anyone suffering financially, and vaccines allowed a rapid economic recovery. So, we should not assume housing arrears will never increase. For further details, see the full version of this paper.

3 topics