Why do most acquisitions fail?

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are often pitched with flashy PowerPoints and lofty promises, but a lot can go wrong. In this piece, we put M&A to the test. We find out the main reasons that acquisitions fail, and how to stay on the right side of M&A as an investor.

It’s impossible to judge the success of an acquisition by a single financial metric. Every deal is different, and there may be strategic reasons for a deal that aren’t obvious in the financials. Instead, we make a subjective case-by-base assessment over whether the largest 1,000 M&A deals over the last 50 years have been successful or unsuccessful.

An initial observation as we started to comb through the data was that the scale of M&A is mind-boggling. Over the last five years, there have been an average of 50,000 acquisitions completed per year around the world – that’s one deal every 10 minutes!

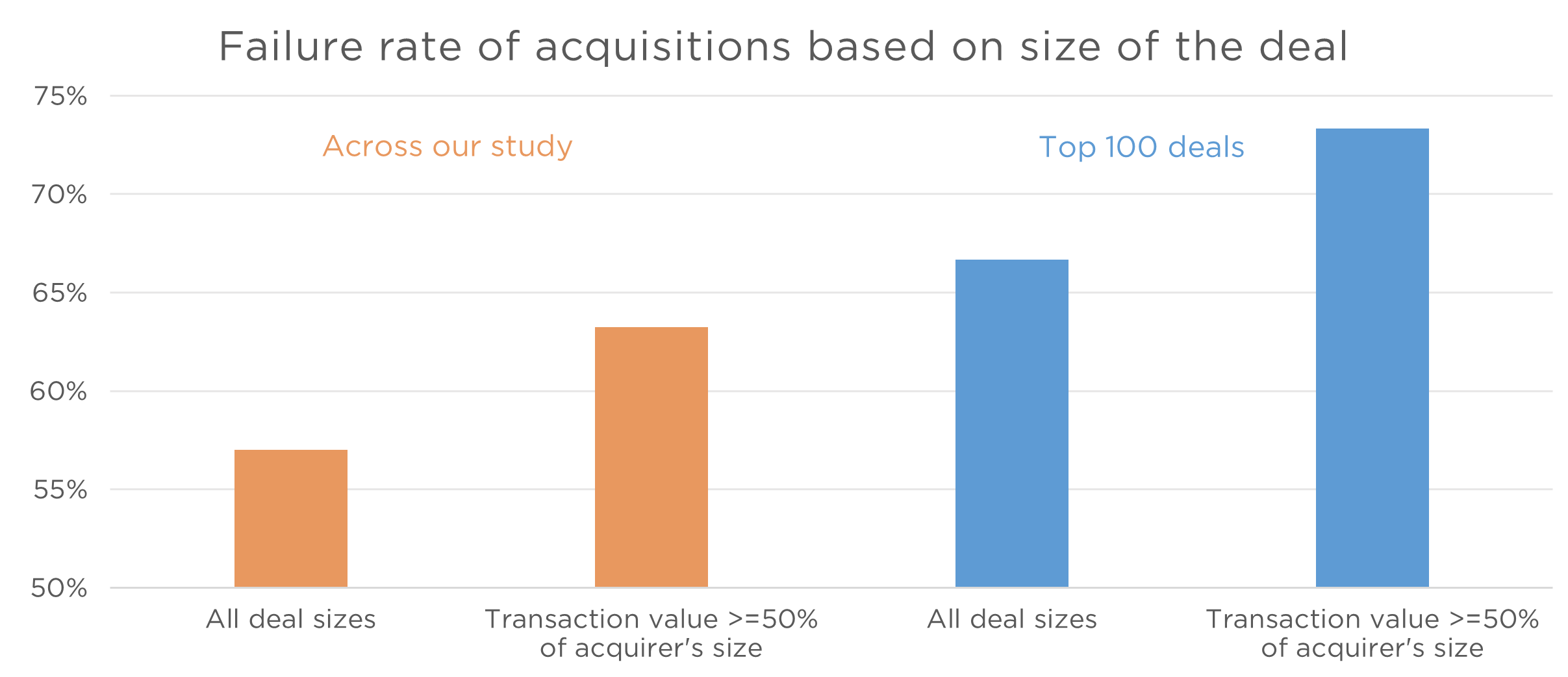

The failure rate of M&A in our study was 59%, and there were two main characteristics that we found to affect the probability of failure.

Bigger isn’t always better

We found that larger acquisitions are more likely to fail. The failure rate for the largest 100 deals in our study (67%) was higher than for the average deal. In both instances, the failure rate was higher again when the acquirer was buying a business at least 50% as large as itself (e.g. a $10bn firm making a $5bn+ acquisition).

Why might this be?

- Acquisitions are difficult undertakings on any day of the week. There are often significant complexities and challenges in integrating cultures, accounting and IT systems, and organisational structures. The larger the deal, the more there is that can go wrong.

- In the meantime, the integration effort is a distraction that can compromise the performance of the acquirer’s core business.

A great example is AOL’s era-defining US$165 billion acquisition of TimeWarner in 2000, which marked the top of the dot-com boom. The idea was to connect AOL’s 30 million Internet subscribers with TimeWarner’s media content, but instead there was a massive cultural clash between AOL’s new economy pioneers and TimeWarner’s old media mavericks. The integration of the two businesses was such a large distraction that it precipitated a decline in AOL’s subscriber base.

At Aoris we have a natural aversion to firms that have made meaningful acquisitions relative to their size. Our investment process favours businesses whose acquisitions are the bolt-on, easily integrated type.

Straying too far

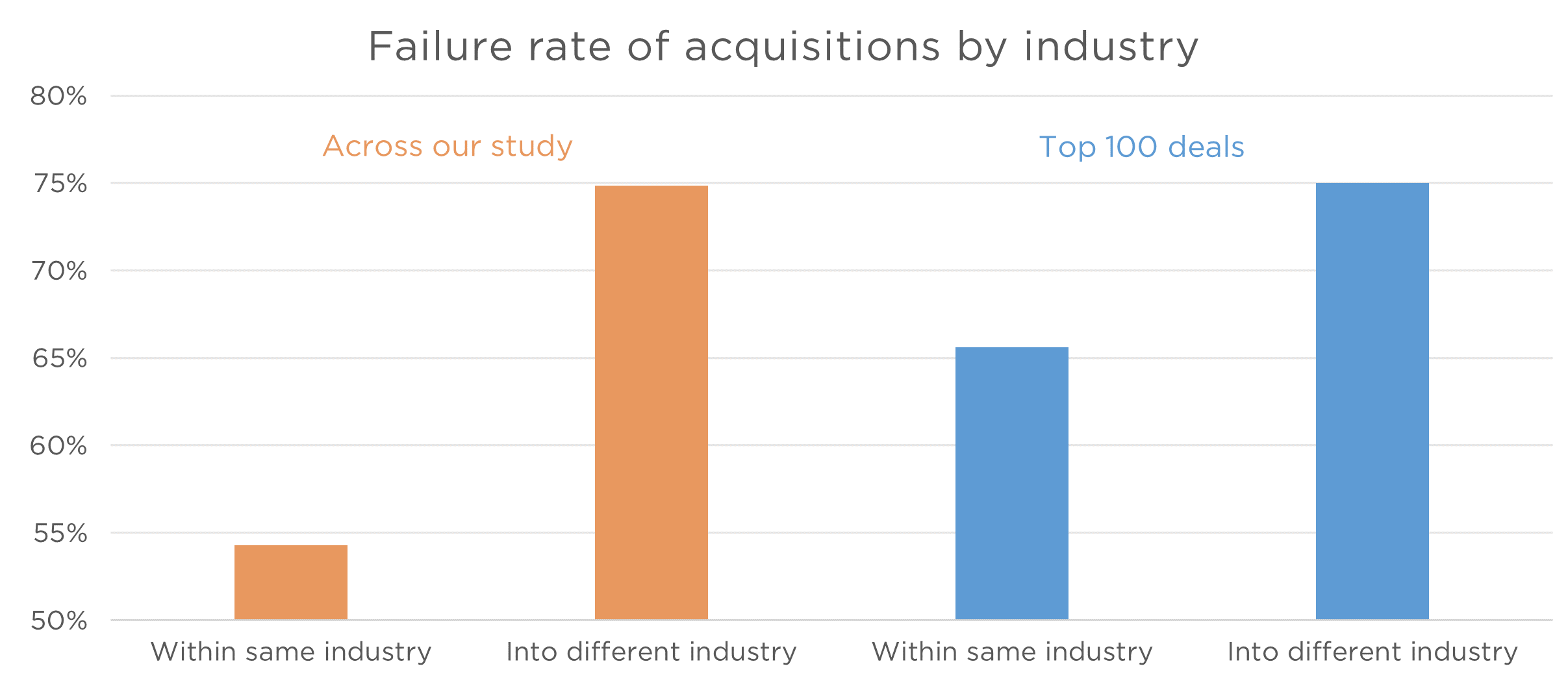

Although M&A is often assessed through a financial lens, cultural and strategic fit are also crucial to the success of any deal. We found that M&A that takes the acquirer beyond its core line of business is much more likely to fail.

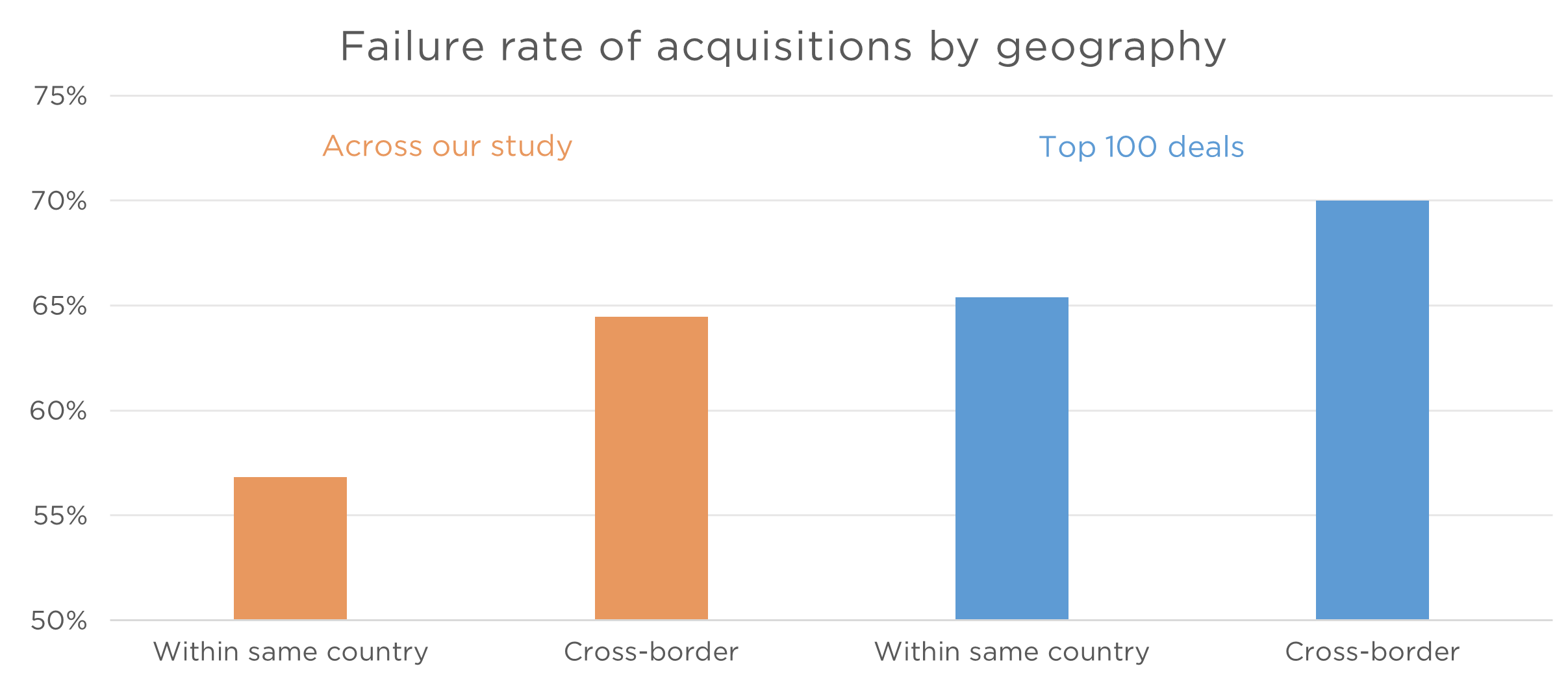

In our study, cross-border M&A had a much higher likelihood of failure than those within the same country. The risks associated with cross-border deals were also magnified for larger deals, as represented by higher failure rates in the top 100.

Our research also suggests challenges with expanding into a new industry through acquisition. A whopping 75% of deals failed when the acquiring firm was buying a business in a different industry, which was consistent across all deal sizes.

Why might this be?

- Firms that are finding life difficult in their existing lines of business might be more tempted to venture overseas or into other industries for a solution.

- Some business models are simply not as relevant in different parts of the world, or the competitive strengths of the acquirer may not be relevant to the new industry.

- When entering a new country or industry it can take time for a business to understand and adapt products to the different cultural, regulatory and customer needs.

The Australian sharemarket is riddled with cautionary tales of companies unsuccessfully looking to expand offshore or into new markets. Wesfarmers had perfected the formula for home improvement stores locally with Bunnings, but its attempt to bring that store model into the UK with its Homebase acquisition were disastrous. Rio Tinto is an incredibly successful iron ore miner, but under-appreciated the different characteristics of the aluminium market when it acquired Alcan for A$44 billion, and has since written off the purchase price by two-thirds.

At Aoris we want to own businesses that are already market leaders, with strong existing businesses that can grow for a long time. In cases where a company is expanding into a new business area, we prefer to see a more considered approach rather than bet-the-house transformative acquisition.

Is there a repeatable model for M&A success?

Studies by Harvard and McKinsey have shown that there is a much higher likelihood of M&A success for companies that make many regular but small bolt-on acquisitions, rather than betting the house on episodic and transformative ‘big bang’ transactions. Companies with this approach tend to make more considered decisions around whether to proceed with an acquisition and have fewer integration issues with these smaller-sized deals.

There are two great examples of this repeatably successful M&A strategy in the Aoris portfolio:

- Amphenol is a world-leading producer of electronic connectors and sensors. It operates in a very fragmented industry, and a key element of the company’s strategy has been to acquire leading connector businesses operating in particular niches, often purchased from the founding family.

- Accenture is the world’s largest IT consulting and outsourcing company. It helps its clients deal with change and complexity, and has done an admirable job of remaining relevant and continuing to grow market share amid rapid technological change. One way it does this is by making regular but small acquisitions that build on the range of problems that it can solve for clients.

You can find our full feature article on the subject attached below.

1 topic

2 stocks mentioned