Why fixed income yield looks mouth-watering now

After another wild month in markets, some clarity to the outlook has been restored as the US Fed held interest rates steady in its November meeting, helping asset markets recover slightly from a bruising period of underperformance. After reaching the lofty heights of 5.00% and beyond in many high-quality Government Bond market yields (including Australian 10-year bonds), this extended pause in global benchmark interest rate hiking will likely mark the top of the interest rate cycle for rate hikes, with markets now considering the evolution for the US Federal Reserve Funds Rate into 2024.

On average, the time from the last interest rate hike to the first interest rate cut is only eight months, however, there has been little that remains average about this unique post-COVID cycle. Should the averages hold, that would suggest rate cuts as early as March 2024.

While it is easy to get caught up in the day-to-day speculation, for long-term investors, the setup is compelling. We continue to see many clients building laddered exposures to fixed income to remove the day-to-day noise and average in over time.

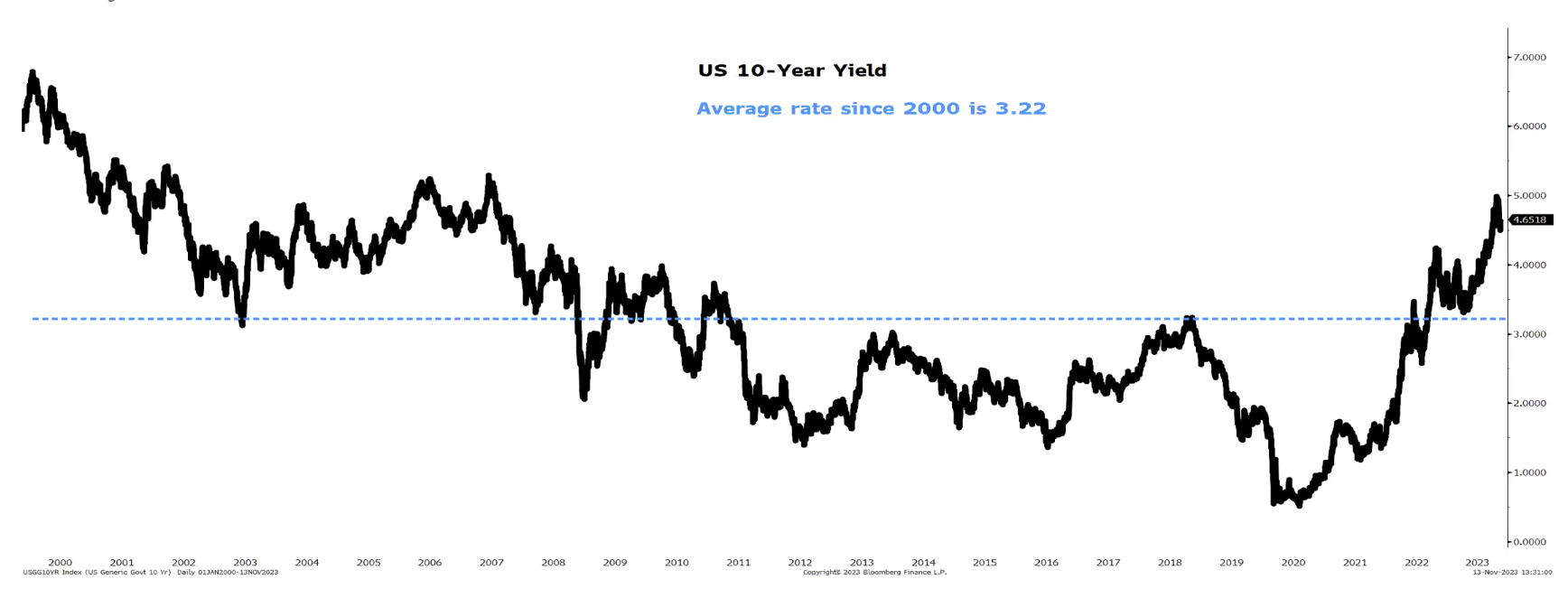

To that regard, the yield available on fixed income looks mouth-watering when compared to the post-COVID average – currently close to 5% in many Government Bonds, when compared to post-GFC averages of around 2.5% or a pandemic low of 0.4% in the benchmark US Treasury 10-year bond yield.

US 10-year Treasury yields

Amid elevated yields that outpace cash returns, it’s only the short-term volatility that is precluding many investors from adding more to their fixed-income allocations, as speculators continue to whipsaw the market.

With medium- and long-term valuations significantly restored, the short-term remains challenging to predict, given the extraordinary spending of the US Government and the different options it must consider to fulfil its borrowing requirements.

US Government spending remains extremely elevated and with an election year coming into 2024, running significant budget deficits – despite being very late in the economic cycle, looks set to continue. This generates an increasingly difficult funding program for the US Government, that now requires enormous issuance of Government Bonds and Government Treasury Bills to satisfy its cashflow requirements.

This program, and its composition between short-dated Treasury Bills or long dated Bonds, has been the subject of much discussion in markets, leading to higher US Bond yields making supply concessions to absorb the higher funding issuance needs.

As yields have risen over October, they have swept many other markets to weaker outcomes as the global cost of capital rises, (benchmarked off the US 10-year bond yield), changing valuation metrics and investor appetite for risk the world over.

There are highly credible alternatives within high-quality fixed income, such as Government Bonds at 5% and many high-quality corporate bond names at between 6.5% - 7%. Given there are also high-yield assets, albeit with added credit risk, it’s clear that not all bonds are created equal.

The hurdle rates for other more traditional asset classes are now very high. Anticipating economic weakness into 2024, we expect a flow of funds rotation aimed at capturing these elevated fixed-income yields. It is important to remember the ’fixed’ nature of the cashflow streams, which provide portfolio certainty for retirees, as opposed to company dividends which can be variable throughout the economic cycle.

The Australian perspective

While the US and European central banks have maintained a steady stance following significant rate increases in 2022/23, Australia saw another recent rise in the official cash rate on Melbourne Cup Day. This increase is expected to add to the challenges for those already facing mortgage stress, leading to a decrease in demand and discretionary spending in the economy.

Unfortunately, this adjustment is unlikely to alleviate the factors driving inflation acceleration, primarily driven by:

- increases in petrol prices (linked to global oil markets),

- utility bills (where wholesale markets have already softened), and

- insurance costs (reflecting higher climate change risks).

1 topic