Why Gerard Minack believes we've been playing the Chinese reopening all wrong

China is cheap, under-owned, and boasts terrific opportunities for EPS growth over the next 12 months. And while famed former Morgan Stanley strategist Gerard Minack believes investors should be "tactically bullish" on Chinese equities, it seems his insights would suggest that investors have been approaching the reopening trade all wrong.

"We talk about the reopening in China, but the fact is, China was never really completely closed," Minack remarked.

"So it's worth noting that the industrial side of China actually had a terrific pandemic."

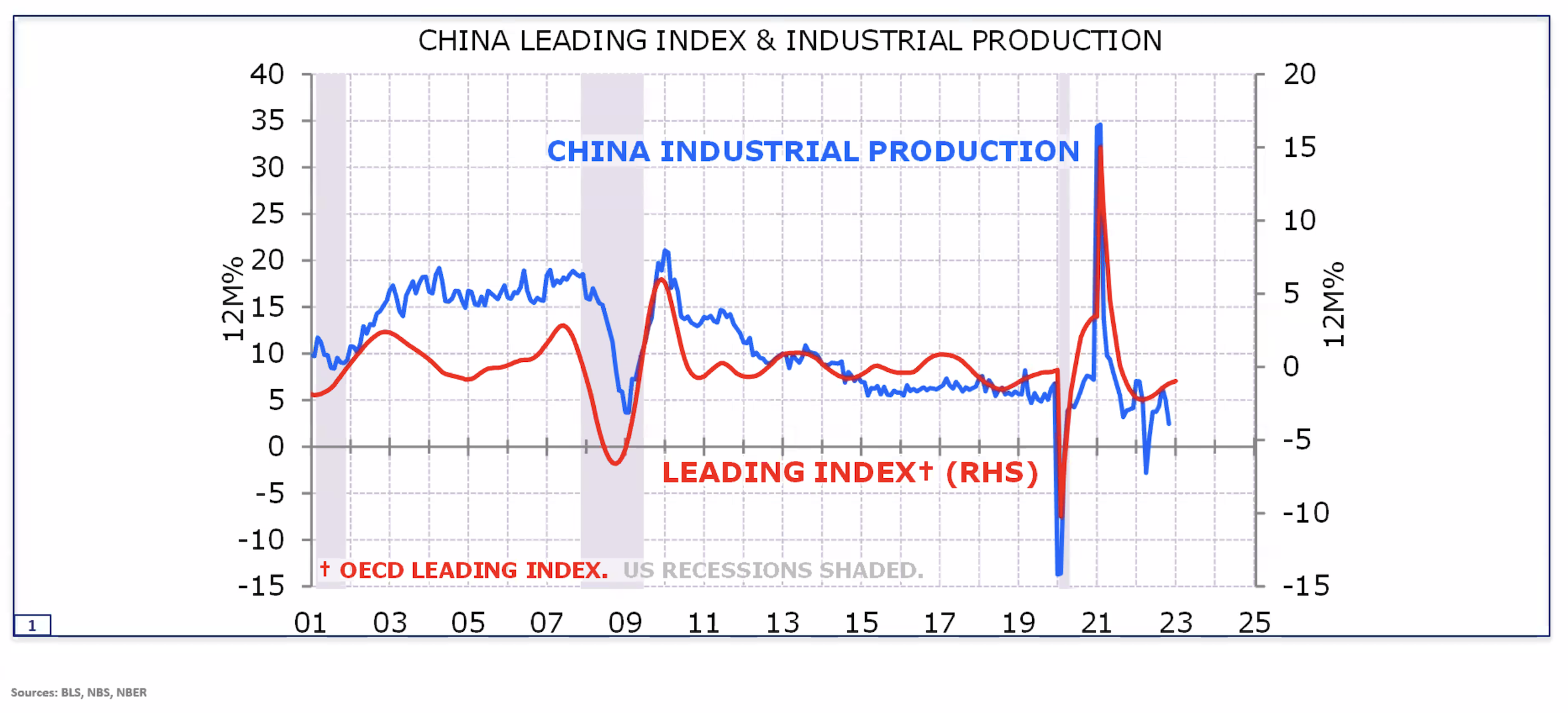

In fact, industrial production in the country saw a significant uplift during the COVID-19 period - with all that online shopping we did at the time turning out to be a boon (see chart below).

"So in terms of what the reopening means for the industrial sector, and therefore, the commodity side of the story, it's a relatively muted outlook," Minack added.

"The really big delta in China is going to be in services and consumer spending... Put very simply, if I was to play the reopening trade, I'd much rather own a bar in Bangkok than I would an iron ore mine in Australia."

For those that don't know, Minack started out in the industry back in 1987, and would later go on to lead Morgan Stanley's macro strategy where he built a reputation for his candid observations of markets, monetary policy and global economics. Here, he penned the 'Downunder Daily' note, which he would later self-publish when he launched Minack Advisors in 2013.

Now, he delivers these same insights to institutional clients, and on Thursday, to lucky viewers of VanEck Australia's 2023 China Investor Symposium.

In this wire, I'll summarise Minack's insights from the webinar, as well as how he himself would invest in China's reopening.

.jpg)

Note: These quotes were taken from a VanEck webinar on Thursday 16 February 2023. You can check out a video recording of the webinar here.

Minack's short-term view: It's an EPS bonanza

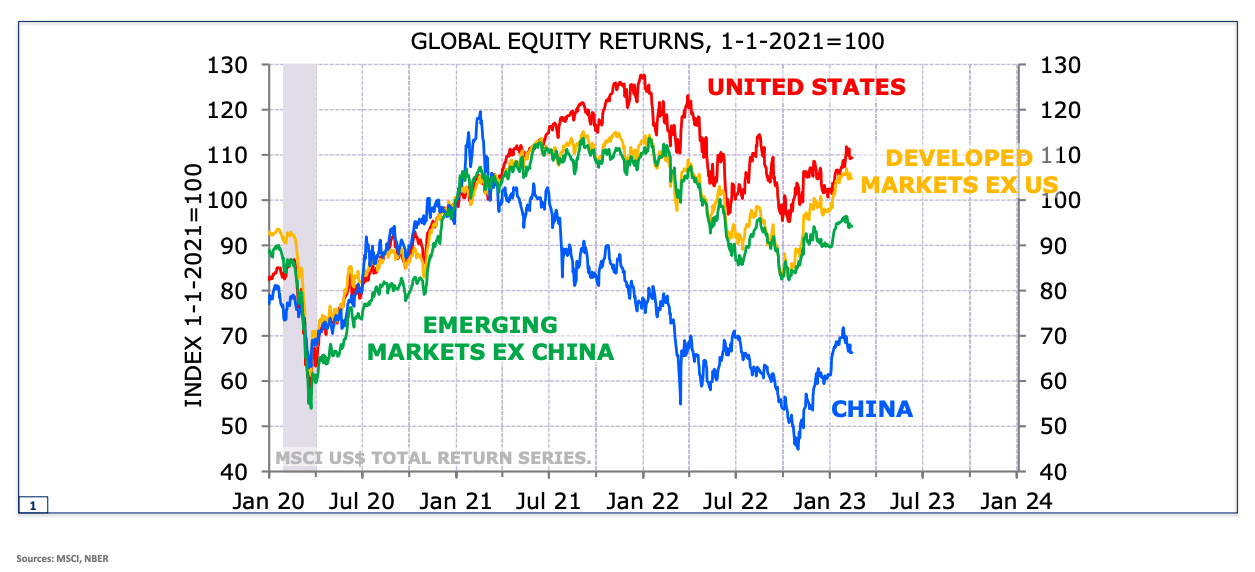

Since the beginning of the year, The MSCI China Index has rebounded nearly 10%, but it is still lagging behind the rest of the world's emerging and developed markets. That's because, as Minack put it, the benchmark suffered from a truly "horrific bear market" (more than a 60% peak-to-trough decline).

"It has since had a 60% bounce, but such is the magic of percentage changes - it is still a long way from the peak," he said.

So what's changed given the 60% rally? Minack pointed to the changes in the CCP's policies, the ending of some restrictions in the property sector, a changed attitude towards tech, friendlier market policies and of course, the COVID reopening as reasons for the bounce.

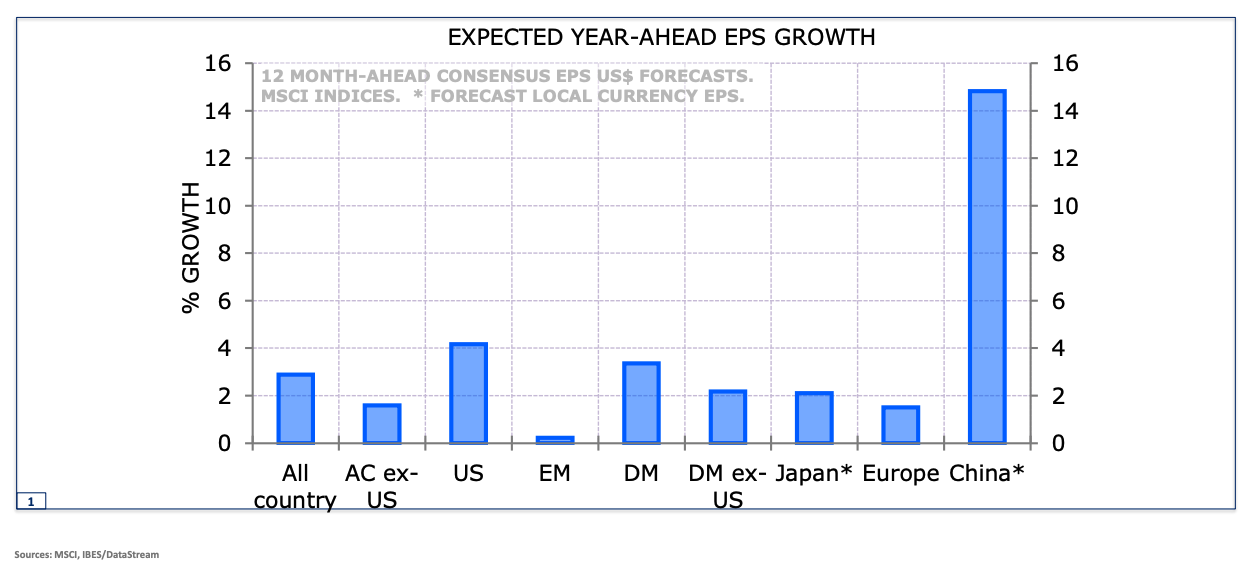

"In terms of the outlook, people have been caught underweight. We've seen big downgrades to earnings in China," he said.

"There have been relatively trivial downgrades to most developed markets but double-digit downgrades to China. The good news looking ahead is that the money is now cheap, and it's clearly under-owned."

In fact, China is the standout rebound prospect according to analysts' forecasts for EPS growth over the next 12 months (see below), Minack added.

Minack's long-term view: China needs to improve the efficiency of its capital allocation

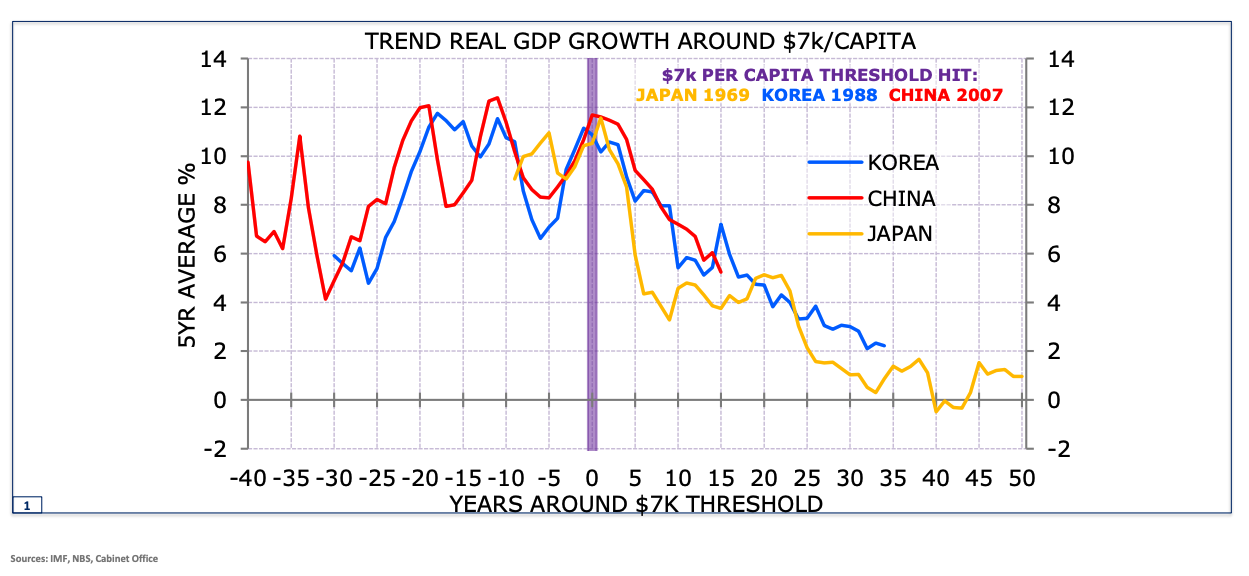

While China has been the world's growth engine over the past thirty years, Minack warns that period is finally coming to an end.

As seen in the chart below, China has followed a very similar path to Korea and Japan - once they hit $7,000 per person in GDP, growth begins to slow.

So is China any different? Minack certainly thinks so... And it all comes down to its reliance on investment.

"Through the fast growth phase, we did see the share of investment in GDP pick up in Korea and Japan as they did in China. However, the CapEx share of GDP has gone higher in China and stayed higher for longer," he said,

This is really a symptom of a different problem, Minack explained.

"The consumer hasn't picked up its role in the recovery story or the structural growth story," he said.

"China's consumption share of GDP is way below what we have seen in Japan and Korea, and it shows very little signs of picking up now."

According to Minack, this gets to the heart of China's real structural problem - it has enormous levels of excess savings.

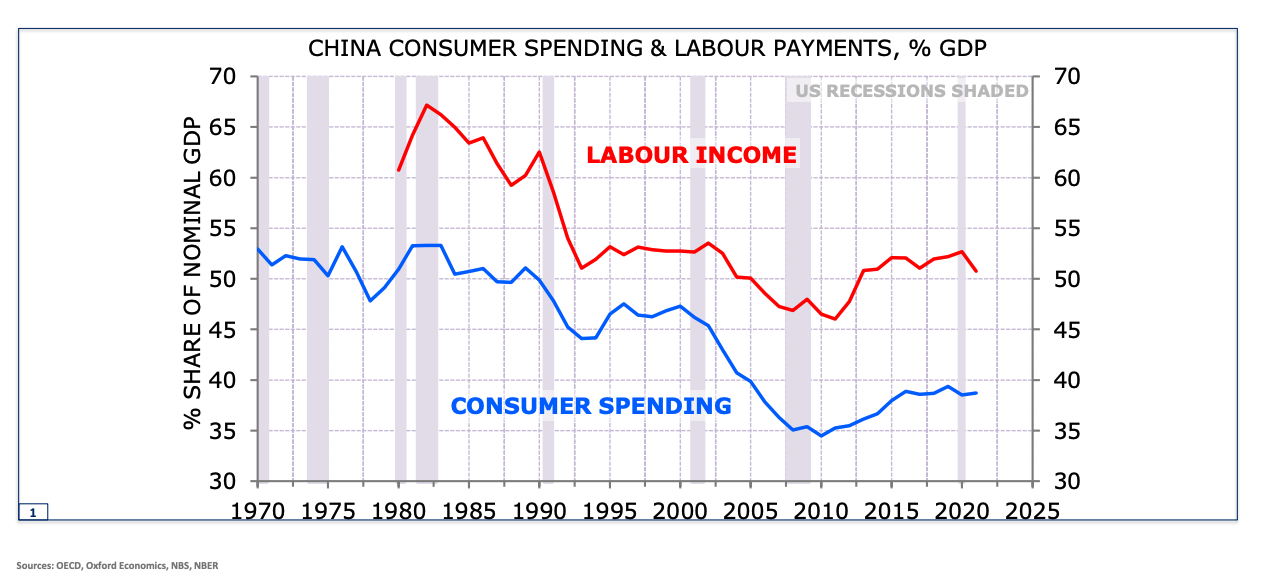

"Remarkably, in China, consumer spending is less than 40% of GDP, even though labour income is about half of GDP," he explained.

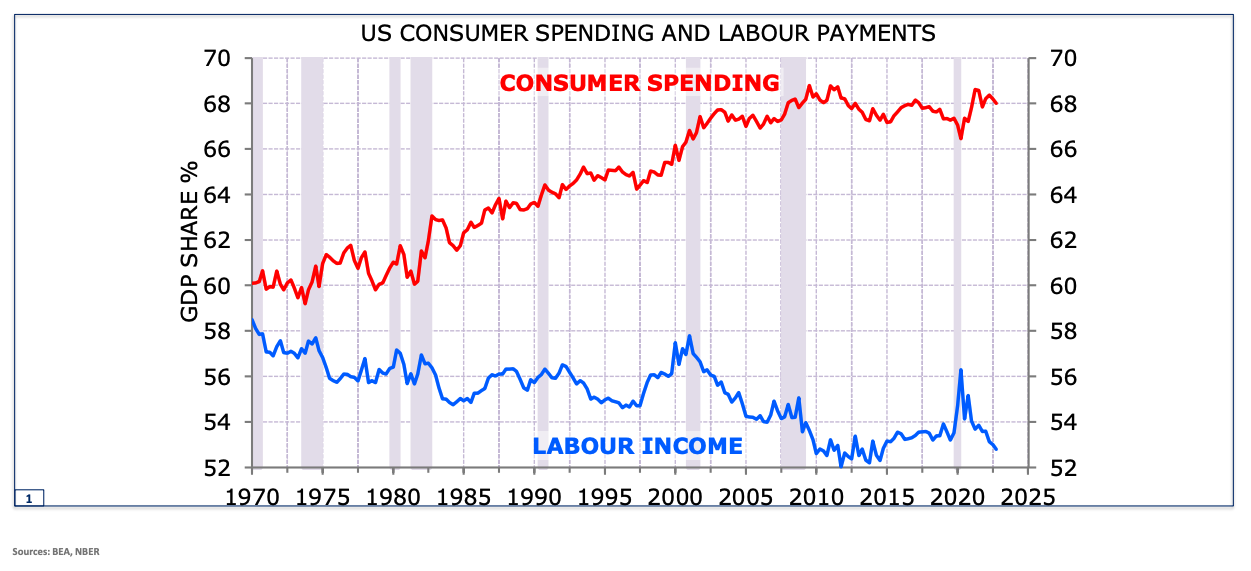

In comparison, in the US where labour income is also around 50% of GDP, consumer spending is closer to 70%.

"The Chinese consumer saves a lot. The American consumer doesn't," Minack said.

These high savings rates have created "a real problem" for the CCP. So what did they do with all this excess savings?

"For 15-20 years, the answer was very straightforward - use the saving to build capacity to make stuff for Western consumers," Minack said.

"And as a result, that fed the massive expansion in Chinese export growth, as you can see from [the slide below]. However, the curtain came down on this story after the GFC when we saw a collapse in Chinese export growth."

However, if policymakers continued to deploy cash in this way, eventually it would result in excess capacity and price deflation. And surprise, surprise - it did.

"If you look at the slide, which shows broad economy-wide prices, as well as producer-level prices, that's exactly what we saw after the GFC - outright price declines," he said.

"That was a toxic mix for Chinese policymakers because it had a corporate sector that was very highly indebted."

Over the last 15 years, Chinese policymakers have had to resort to CapEx to stimulate the economy - as Chinese consumers have continued to save instead of spend.

"They did a massive CapEx expansion in the aftermath of the GFC and then you can see them tapping on the accelerator in each subsequent downturn, but quickly lifting it off the accelerator again because they wanted to try and get off this addiction to investment," Minack explained.

"The biggest macro consequence of this excess CapEx has been diminishing returns - diminishing returns in both an economic sense and a financial sense."

You can see China's diminishing economic returns on this CapEx in the chart above. As the line lifts, more investment is required to generate returns for corporates, the government and households.

"That deteriorating payoff means that really CapEx is being wasted and returns are falling," Minack said.

So what does this mean for investors?

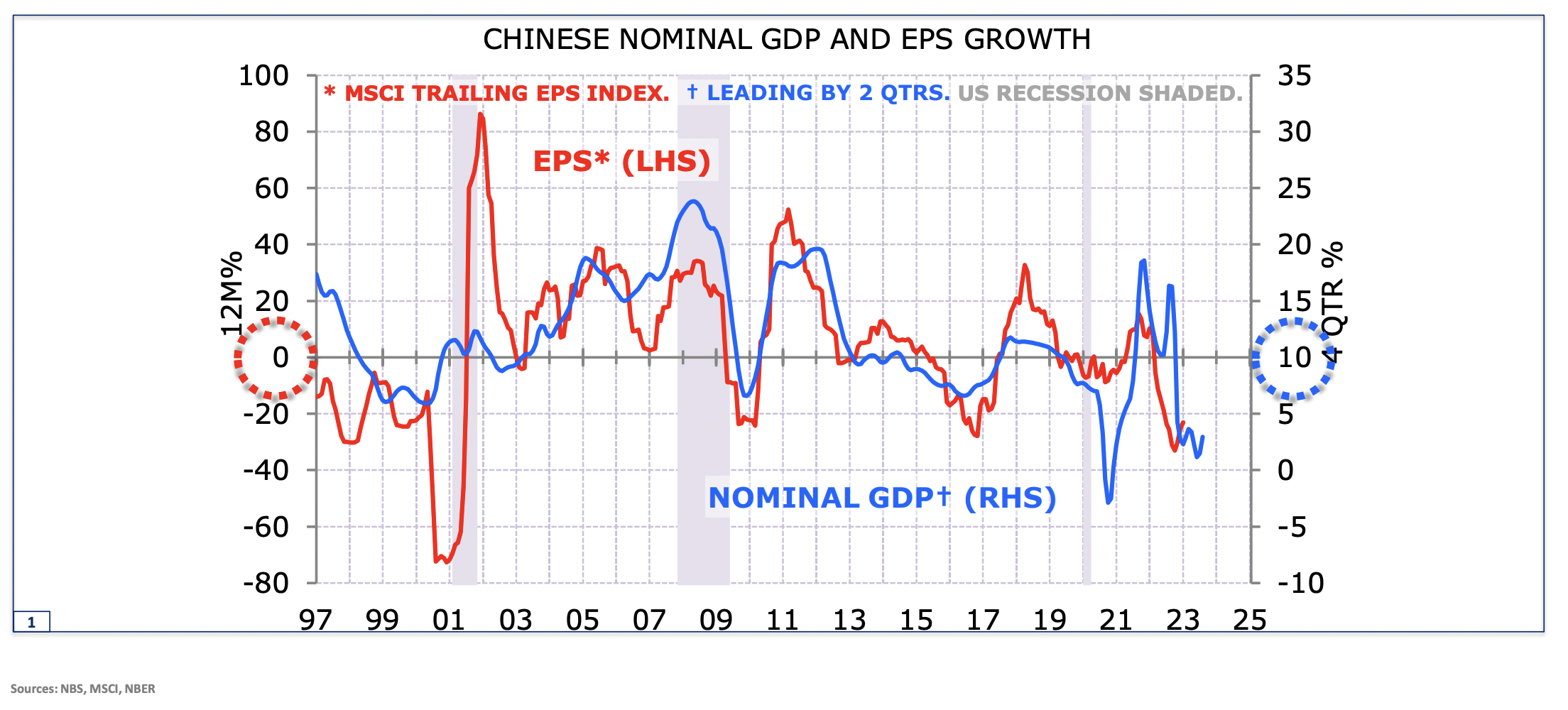

"What differentiates China from other markets is the axes I've needed to use to make the correlation work," Gerard explains (see chart above).

"The left-hand axis is the earnings axis, zero there corresponds to 10% on the right-hand axis, the GDP axis. So in other words, Chinese corporates, in aggregate, have been unable to grow their EPS except in the environment of double-digit nominal GDP growth."

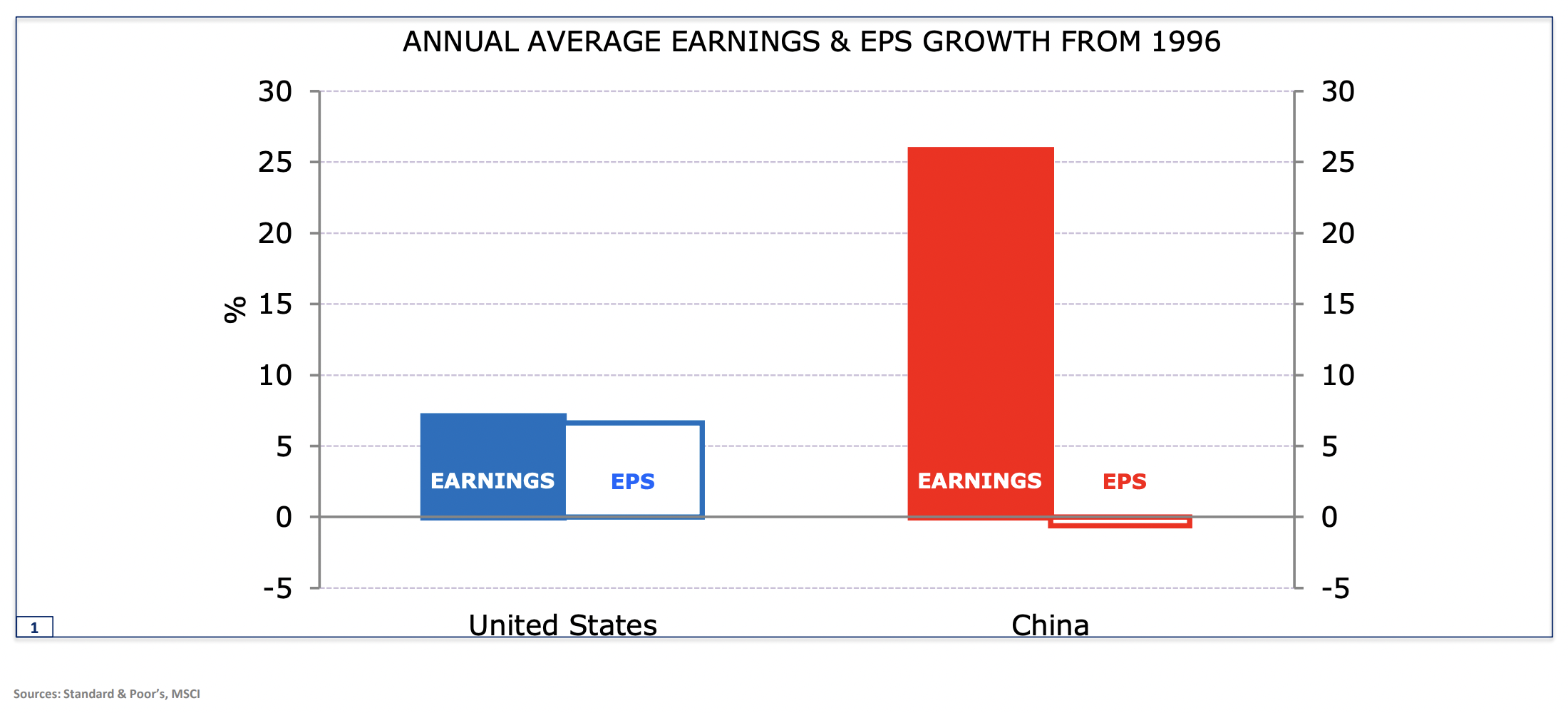

That said, China has grown much faster than its second global superpower peer - the US. The annual growth rate for China has been 11.5% since the mid-90s, while the annual growth rate for the US has been around 4.5% - translating to faster aggregate earnings growth.

Earnings growth for the S&P 500 has been approximately 7% over the past two decades, for the Chinese Index, aggregate earnings growth has been 26% (and closer to 11% for companies), far faster than the US.

However, this has not translated into returns for investors.

"The S&P 500 has returned around about 9% per annum since 1996. Whereas China is just 2.5%," Minack said.

"So what's going on here? Well, the trick is, it's not earnings that drive equity performance, it is earnings per share. And if I compare earnings per share between the US and China there is a massive gap." (see chart below)

For China to be a decent long-term investment destination for global investors, the country needs to improve the efficiency of its capital allocation, he added, as Japan has done over the past 25 or so years.

"It's not impossible, but we need to see it. And so far in China, there's no sign of a structural shift that would improve the medium-term outlook for Chinese equities," Minack said.

China and Australia: The reopening trade is in services, not commodities

According to Minack, the real way to play the China reopening is through services and consumer spending, not through commodities and locally listed miners.

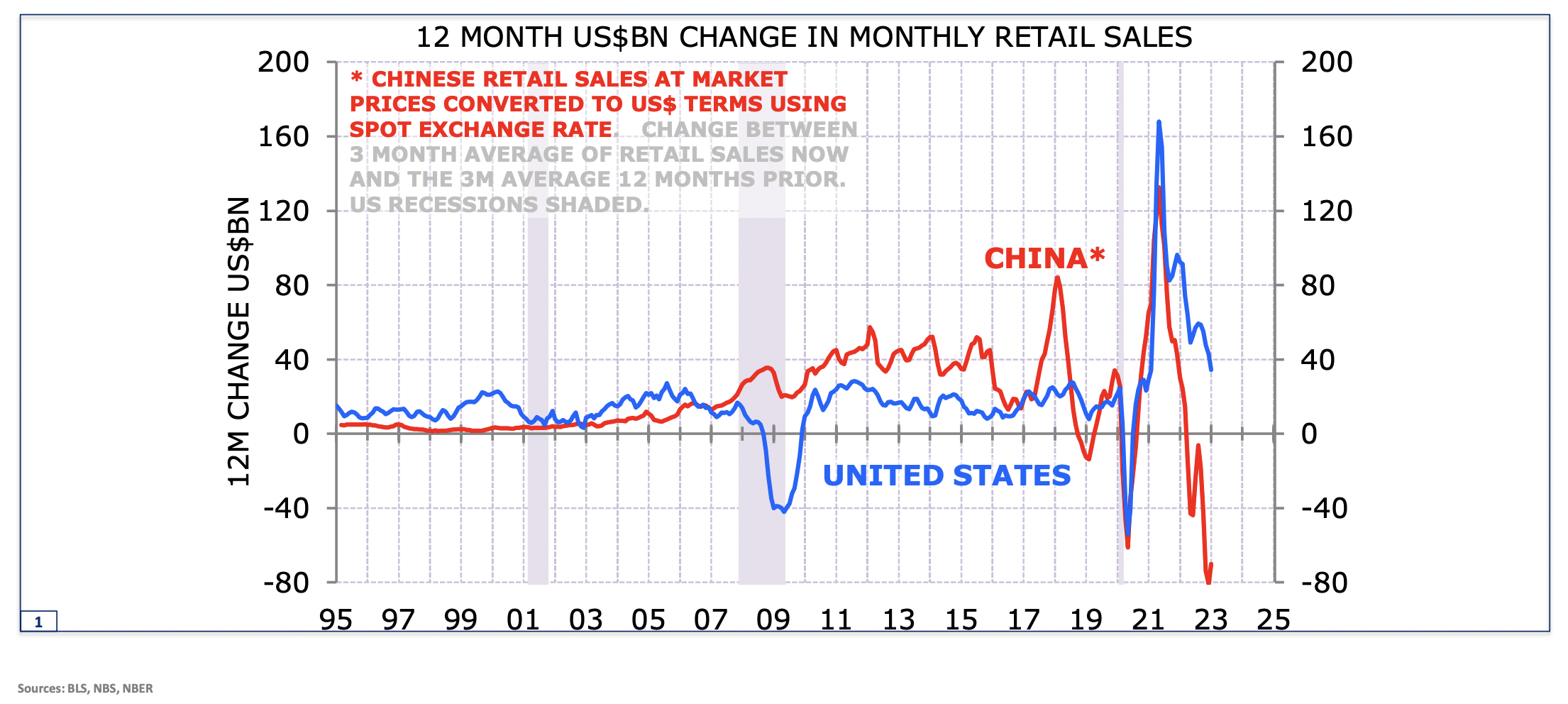

The slide below highlights the 12-month change in monthly retail sales in the US and China. For the US, the rebound has seen retail sales running $100 billion higher than they were last year. Even now, sales are still $40 billion per month higher than where it was, Minack explained.

"The Chinese consumer, of course, has been locked down last year. That will rebound and that will ripple out across service industries and wherever good Chinese consumers spend their money," he said.

"Put very simply, if I was to play the reopening trade, I'd much rather own a bar in Bangkok than I would an iron ore mine in Australia."

But China is our most important trading partner? And aren't the vast majority of our exports to China commodities? Well, yes, Minack said. However, amid the trade embargoes of the last 18 months to two years, Australia's aggregate export growth has never been faster - we have been able to sell those commodities to other parts of the world.

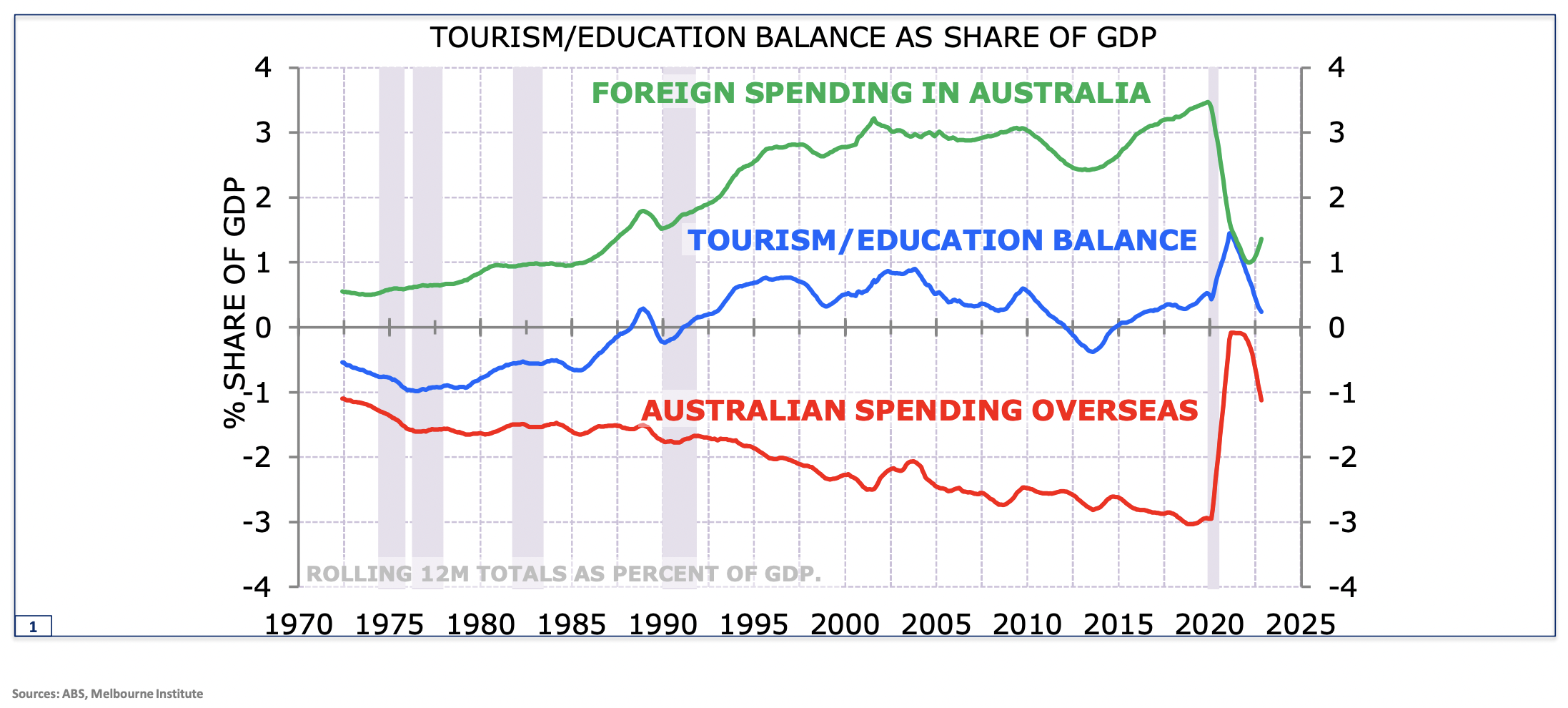

The chart below highlights trade flows. The green line shows how foreign spending in Australia has collapsed, Minack explained.

"That's going to pick up, but what's also going to pick up is the red line, which is our spending overseas, which is going to become more of a negative balance," he said.

"So net-net, there's not a huge upside here, but there will be regional differences. The places where Chinese tourists and Chinese students live will clearly see some upside from this reopening trade.

"Yes, we're seeing a reopening in China after the political problems that caused lockdowns and several anti-market measures. These are being reversed. That means we will see a rebound. I suspect it's got further to go. But in my view, it's a trade, not a fundamental sector or position."

So, beyond the bar in Bangkok, how should you invest in the China reopening?

Don't overthink it, Minack said.

"People are hugely underweight just the key Chinese benchmark, so I'm happy to buy the market in aggregate," he said.

"We clearly are going to see a rebound in listed sector earnings growth from what has been very depressed levels. And the policy changes towards the individual sectors, such as the tech sector, means that they will also enjoy a rebound."

That said, he warns this is not a long-term trade.

"My point, however, is don't overstay the welcome either," Minack added.

"There is substantial further upside, I would say on a two to three-quarter view, but once we recoup two-thirds of the losses that we've seen over the last 18 months, then I'd reassess on how the world's looking and how Chinese policies are looking."

2 topics