Why global bonds are in their first bear market in 70 years

It may have been former US President Gerald Ford who once remarked "our long national nightmare is over", but bond traders are finding all too quickly their nightmare has just begun. Records are being shattered in most countries, most instruments, and most time horizons. It's wreaking havoc on other asset classes like equities and currencies. And it's given the 60/40 portfolio a year to forget.

The bear market of 2022 comes after a multi-decade bull run for prices. The MarketWatch-compiled index has the global bond market wiping out a decade's worth of returns in less than nine months. To put it another way, the yield on these traditional safe-haven assets has been low for some time - as the next chart shows:

And while Australian investors love (and I do mean, love) their stocks, you cannot invest in markets without some basic understanding of how the bond market operates. It's where all the big money trades are made, and the first place to see the market's reaction to breaking news. Sometimes, it even provides the odd famous headline.

In this, the first of our latest collection into all things global bonds, I'll take a look at the statistics and the environment that is the global bond market. We'll also get some insights into the turmoil from Jay Sivapalan of Janus Henderson, Michael Korber of Perpetual Asset Management and John Likos of BondAdviser.

So sit back and enjoy as we take you through the state of the fixed-income world.

Fast Stats, Fast Calls

Before we get into the experts' views, I thought it'd be worthwhile throwing some fast statistics at you. The aim is to demonstrate how remarkable - and unprecedented this year has been for bond observers.

- Bank of America, Deutsche Bank's data suggests global bonds are in their first bear market in 70+ years

- The Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index is seeing its first bear market since the index was initiated in 1990

- Vanguard's total bond market index is down 14% year-to-date

- The 2s/10s curve has now been inverted (as of writing) for more than three months, and recently, the 10-year/3-month curve in the United States inverted for the first time ever.

...and my personal favourite, if only because of the sheer size:

What happened and what's changed?

As has been repeated ad nauseum, global central banks are in a race to fight inflation and are doing that by hiking interest rates. The hikes will curb demand, increase the cost of servicing debt, and (hopefully) encourage some level of leniency in the job market naturally. This goal hasn't changed for the most part.

As recently as this week, Federal Reserve officials in the US have repeatedly said they will be resolute - not pivoting from their current policy path until inflation is substantially under control. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank continues to openly discuss whether the next hike needs to be a 50 basis points hike or a 75.

Jay Sivapalan, portfolio manager at Janus Henderson, argued that the problem isn't the process but the timing.

"While the policy normalisation process was always going to be complex, this cycle has coincided with highly correlated drawdowns in equity, property, credit, and government bond markets," Sivapalan says.

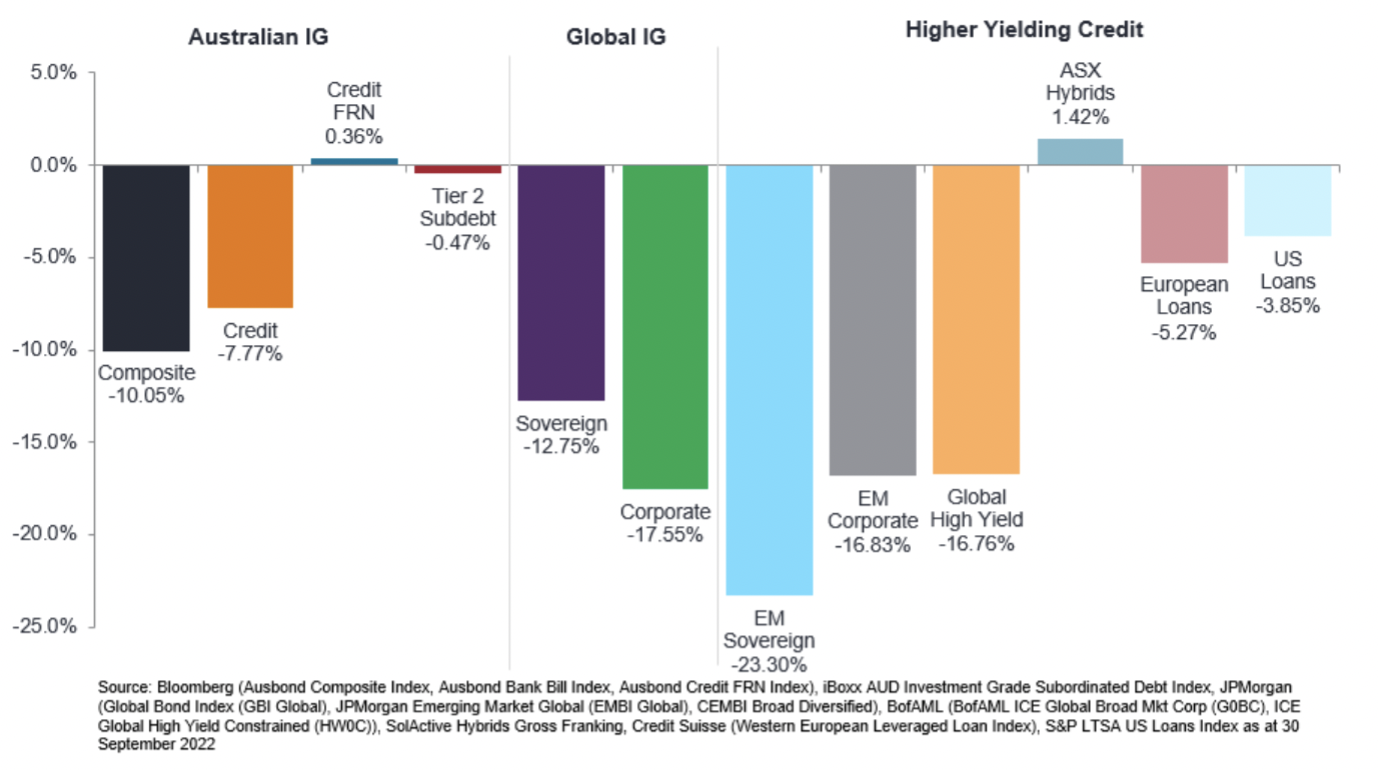

The coordination of this "talk tough" program, as Sivapalan describes it, has been reflected in every asset class - and it's in the bond market where the moves are arguably most drastic, as this chart shows:

While everyone got this coordinated message, some like Michael Korber at Perpetual argued the message was not always clear.

"I would contend that the narrative was not always “well flagged beforehand”. In 2021, central bank rhetoric pushed out tightening expectations which have contributed to the aggressiveness of rate increases and the severity of the selloffs in bond markets," Korber says.

Then, there's the data. While it can be backward-looking, it is the best measure (at present) of tracking the state of the global economy. So far, most of the inflation surprises have generally been negative in G10 countries - and any negative surprise is more than enough for John Likos at BondAdviser to explain the moves we've seen.

"Material surprises, be they data or policy, can lead to rapid price moves across asset prices - especially government bonds. Most recently, a higher-than-expected inflation number in the US has led to a sharp upward repricing of inflation expectations and, in doing so, boldened the resolve of the hawks in their running stand-off against the doves," Likos says.

What does this mean for the RBA?

Australia has always been a different case from the rest of the world. Our mortgages are on variable rates, our commodities are the envy of the world, and the Reserve Bank's yield curve control experiment of 2021 was not repeated by every other major economy except Japan. We also don't have what the Americans have - major yield curve inversions across the fixed-income spectrum. And that's a relief worth celebrating, says Korber.

"We do believe that the Australian economy can be resilient. While the economic backdrop looks similar, the RBA faces arguably a more favourable set of challenges with a potentially more powerful mechanism," Korber says. "From the perspective of a credit investor, a lower terminal rate and avoiding – or engineering a shallow – recession would be supportive for domestic corporate bonds."

Likos shares the view that the RBA will not likely hike as far or as fast as its global counterparts, but did note there is a big risk by not moving in lockstep.

"While the RBA doesn’t want to risk going too fast and breaking anything, they also run the risk of falling further behind the global rate hiking cycle while domestic inflation hits long-term highs. The real risk is the inflation can is being kicked down the proverbial road only to confront us again in a much more combative manner in the future," Likos says.

Whatever your view, central to this entire process is the need to anchor inflation expectations. When consumer opinions on inflation run out of control, so do demand and prices. Sivapalan says the RBA needs to be very cognisant of that risk.

"The desire to anchor inflation expectations shouldn’t be underestimated as the alternative can be more damaging over the medium term. The RBA will likely cap out on the tightening path earlier than in other countries, due to a pivot towards financial stability concerns and the impact on heavily indebted households," Sivapalan says.

What's next?

The answer to this question will likely depend on the US Federal Reserve, as it's their rate hikes that change the shape of global rates. Even if you have no exposure to the bond market as an investor, you still have to pay attention. High yields make it more expensive for companies to borrow money, and that extra cost could lower earnings expectations. Combine that with a strong US Dollar and those earnings could look a lot worse than when you started.

In part two of this series, we will take a look at the case for Australia. Specifically, how and in what ways Australia might have a different experience from the rest of the world. Plus, we'll unleash our experts' top trade ideas.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

I'll be in charge of asking the questions to Australia's best strategists, economists, and fixed income fund managers. If you have questions of your own, flick us an email: content@livewiremarkets.com

2 topics

2 contributors mentioned