Why has value investing been underperforming and how should it work

Avenir Capital

Value investing is one of the oldest and most intuitive styles of equity investing. Often more formally defined as an investment strategy of aiming to pick stocks that are trading at a discount to their intrinsic value, the commonly understood short-hand is investing in stocks that have a cheaper statistical valuation ratio/s such as price-to-earnings (P/E) or price-to-book (P/B) than the broader market.

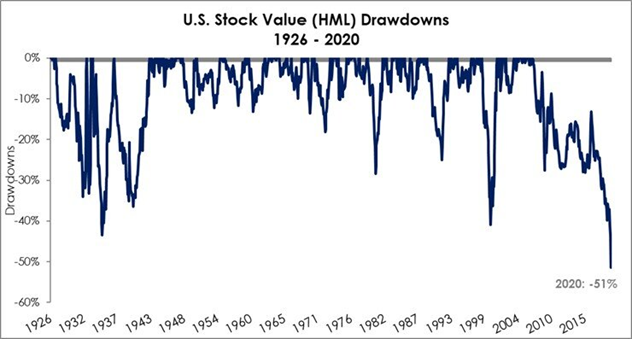

However, there is no doubt “value” has underperformed “growth” or “momentum” styles in recent times and this has been exacerbated by the outperformance of US mega cap tech stocks during the early stages of the Covid-19 equity market selloff. Before tackling some of the reasons for value’s underperformance as an investment style – at least when defined quantitively by traditional value investment metrics like price-to-book (P/B) and price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios – it is worth noting just how severe this underperformance is in a historical context.

As of March 2020, Value factor is down -51% from the peak reached 14 years ago.

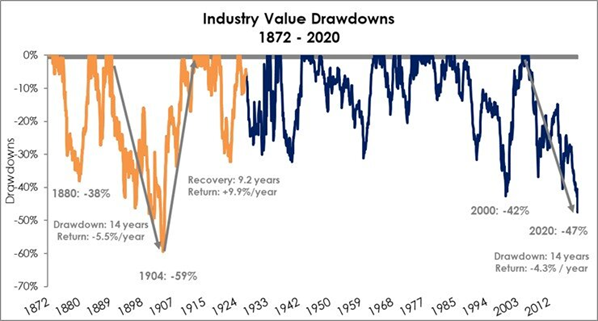

Drawdowns of the value portfolio return in excess of the risk-free rate going back further to 1872. Source: Cowles at Yale.

As we see it, there are 4 key narratives around the underperformance of value stocks compared to growth stocks that we will outline below.

1) Winner-take-all economics (“monopolies”)

To many, the principal reason for value’s underperformance can often be summed up as ‘this time it’s different.’ That so called ‘old’ economy stocks don’t justify a return to previous valuation levels and revenue growth rates when compared to the new breed of capital light business models epitomised by ‘big tech’. This narrative ultimately hinges on the belief that big, monopolistic technology and e-commerce platforms (i.e. winner take all) firms will continue to grow market share in the future at the same rate as in the past and continue extract rents from their ‘ecosystems’ without a meaningful competitive or substitution response. It also often assumes that traditional business models in many other industries are under threat from these businesses or general obsolesce, do not innovate, integrate these platform-style businesses into their existing business practices in a value accretive way and/or mount an effective competitive response.

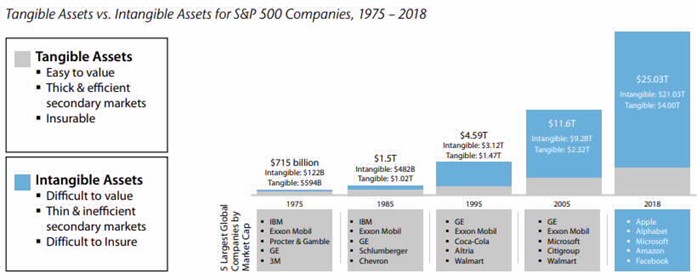

2) Tangible versus intangible assets,

One argument put forward is that new economy ‘glamour’ stocks with fast revenue growth and highly scalable business models with ‘winner take all’ (read: monopoly) characteristics, particularly in the business and communications services, software-as-a-service (SAAS) and biotech sectors, don’t capitalise their heavy, but valuable, spending on brand, IT, human resources, and R&D. This skews their book values downward compared to their share price, making them appear expensive on a price-to-book value basis compared to cheaper, low-growth ‘old economy’ firms that have lots of tangible assets like property or plant and equipment. This ties straight back to the most traditional, academic definition of value being price-to-book (P/B).

One study quotes data that suggests that investment in intangible assets is running at twice the rate of tangible assets in the US. This has caused a systematic ‘misidentification’ of what value truly is, and adjusting for this intangible asset investment by capitalising it so it appears in the ‘book value’ of assets on balance-sheet means that new economy firms actually start to look like better value when using traditional value metrics compared to old economy firms.

Source: Aon, (VIEW LINK)

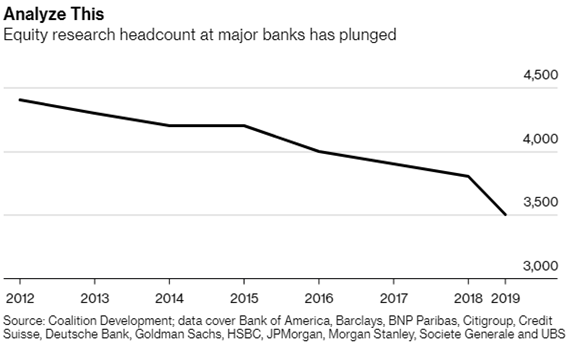

3) Lack of analyst coverage,

It has also been argued that the trends outlined above are compounded by a declining number of professional equity analysts covering stocks outside of the mega-cap growth names that generate meaningful capital markets revenues for investment banks. This concentrates investor attention on these large cap stocks at the expense of less well-known stocks. Whilst we believe this decline in research coverage in many ways presents opportunity for active managers who do their own in-depth fundamental research, the overall reduction in in-depth equity research of less well-known companies arguably reduces the efficiency of the price formation by the market in less well known and/or smaller market capitalisation companies.

Source: Bloomberg (VIEW LINK)

4) Interest rates and valuation discount rates

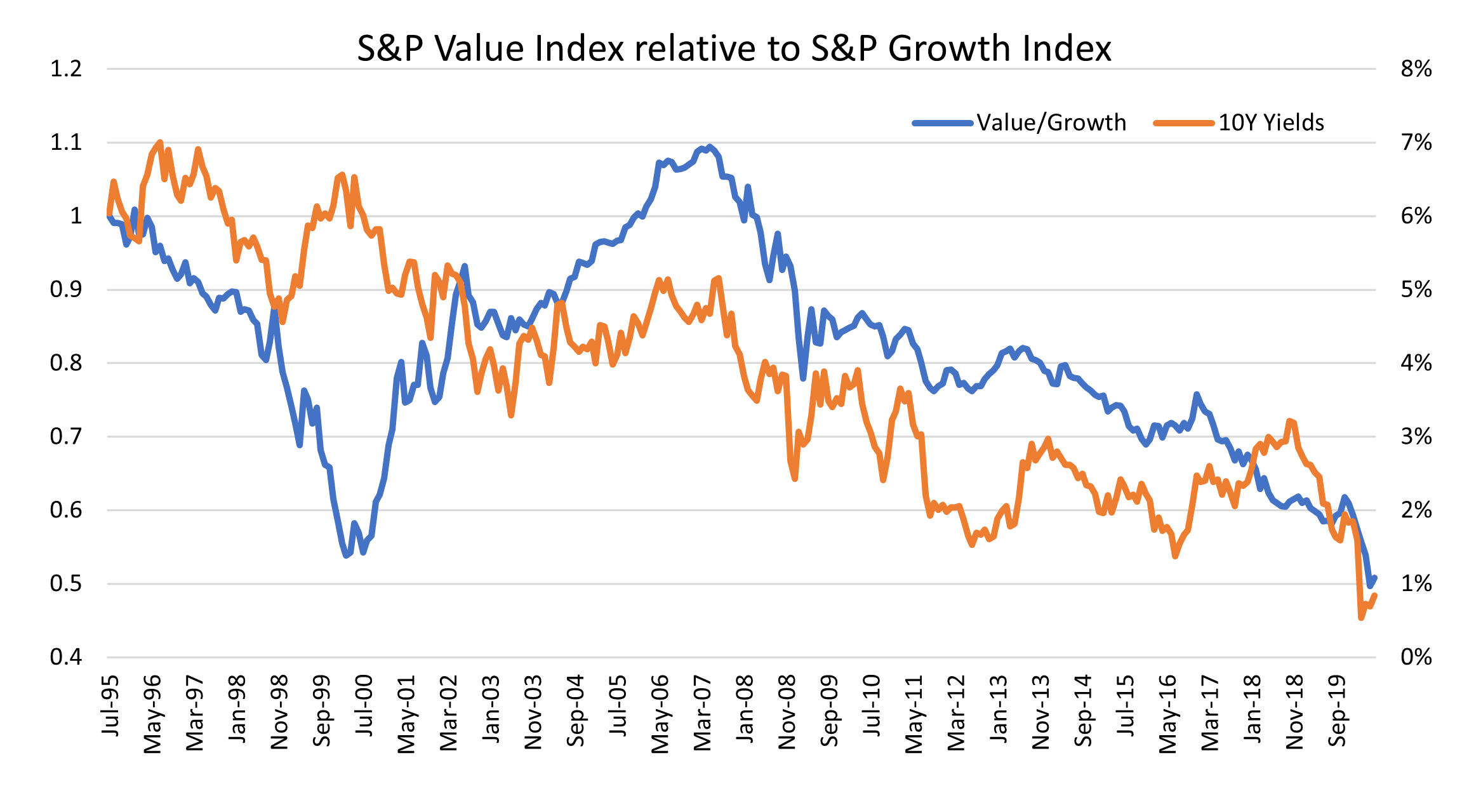

Another central argument is that low interest rates, and the associated lower hurdle rate of return (known as the discount rate) that investors need to invest in riskier assets, exacerbates demand for ‘long duration’ stocks. That is, investors seek stocks with potentially large, but less certain and more distant profits, at the expense of firms with historically proven business models and more predictable near-term cashflows.

It follows then that investors have been less willing to supply capital to these proven companies at the expense of financing the expansion of high growth firms, increasing their market capitalisations and access to financing at the expense of their ‘short-duration’ brethren. This has manifested itself in the massive outperformance of growth stocks compared to value stocks - which are at extreme levels of valuation dispersion.

Source: Avenir Capital, S&P Capital IQ

So how should Value investing work?

But all of this doesn’t answer the question, what is value?

The simplest, and best explanation in our view can be found in a dictionary, not a finance textbook. The Oxford dictionary defines value as

“The worth of something compared to the price paid or asked for it.”

It then follows that active investors are trying to find stocks that are worth more than the current price (i.e. value greater than price), and passive investors buy everything, assuming all prices are correct (that is, value equals price).

For this to be true, passive investors rely on active investors to set the price. And to incentivise active investors to do this, they must believe that there are securities where value is greater than price.

To crystallise this, they must get in early, find the bargain and wait for other investors to realise this and buy the investment until such time as value equals price. This basically describes the process that every long-only investor undertakes, irrespective of how they define ‘value’.

It is important to remember that the value of an asset in finance is meant to be the discounted value of future cashflows returned to investors. Assets whose statistical valuation metrics are higher (growth stocks) have larger future expectations of profit growth built into their present valuation than value stocks.

As such, it is reasonable to expect that growth stocks whose future expectations don’t materialise will naturally suffer sharp price reversals.

According to renowned tech commentator, tech entrepreneur and academic Scott Galloway, Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook need to add more than $USD 500bn in revenue to their income statements in the next 5 years to justify their current revenue multiples if their implied promise to investors is to double the stock price over that time period . That is a staggering amount of money, around a third of Australia’s GDP, and will inevitably result in them competing aggressively against each other in industries like search, education, healthcare, financial services, cloud computing, retailing and advertising more broadly.

Sometimes the market forgets these principles in the way it prices companies, but fundamentals usually rule over the long term, as the management and private market investors in fast growing ‘unicorns’ like WeWork and Uber have discovered in recent years. That is not to say that some growth companies, notably US tech “FANMAG” companies (whose collective market capitalisations exceed all stock exchanges globally except the US market itself and Japan ) have not wildly exceeded the expectations of early investors. It’s just that the entire market recovery after the first stage of the COVID-19 sell down was driven by the performance of these stocks.

Cliff Asness of AQR Capital sums up why value works at all with this quote:

“It does not depend on getting the big events or trends right. It does not depend on having perfect accounting information. Certainly, it does not require a lack of massive technological change over time. No matter what the situation, it simply needs investors to overreact. Companies that are cheap tend to be a bit too cheap for whatever set of facts exist at the time, and expensive companies need to tend to be a bit too expensive” (Asness 2020)

With the media and many investors being fixated on the ‘death of value’ investing, our fundamental belief that making investment decisions guided by a firm understanding of the intrinsic, cash-generative value of companies over the long term is like gravity – you may be able to resist it for a while, but it will always bring you back to earth eventually.

Learn more

Avenir Capital is an Australian based investment manager, specialising in value-oriented global equity investments. You can find out more by visiting our website.

Stay up to date with all our latest insights by hitting the follow button below.

3 topics

Adrian Warner is the Managing Director and Chief Investment Officer of Avenir Capital and is responsible for the portfolio management of the Avenir Global Fund. Prior to founding Avenir Capital, Adrian worked in private equity investment in...