Why I am frustrated by the state of ESG

This will be a missive wire on an important topic I feel very strongly about. This is the current state of progress towards (truly) sustainable investing in respect of the trend towards the evaluation of portfolios using Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) metrics.

The short version of what I have to say is this:

I do not think that the present focus on ESG investing is delivering portfolios that represent anything approaching a sustainable prescription for global capital allocation. What is worse, it may actually be very damaging.

That is a pretty damning point of view to offer, and I daresay controversial.

If you want to see the example, skip straight to the end. There I show how the hidden biases of one popular ESG scoring system would lead us to invest in supermarkets but not food production, food processing, or distribution.

In this business, of funds management and financial advisory services it is generally thought that there is complete alignment between the views of corporate management, business development, the research and portfolio management teams, and legal and compliance.

While much of what I am about to relate would be considered controversial, the most controversial element would likely be this:

In my twenty-five years' experience of professional funds management, the most damaging recurring business phenomenon is the need for those whose job it is to deliver on the client expectation to reclaim, from fund marketing, the illusory client expectations that were specifically created in order to win new business in the competitive game of funds management.

Obviously, that is a contentious statement, and probably considered divisive in some circles.

However, in my defense, I will present a very simple and easily understood conundrum that I faced, this week, in serving one of my clients, as best I can, within the limitations of industry standard ESG frameworks that give little thought to the realities of the world we live in.

I do not know how to be professional and not say what I am about to say.

It is going to irritate many people, but some leadership has to be shown on this point.

It is time to drop the industry ruse and get serious about the nuanced nature of investing to supply what society actually needs, while remaining committed to a sustainable future.

Let me now relate the crux of the problem.

The global economy is an interrelated system where the supply of any one finished good or service very often depends on myriad inputs, some of which may not be readily substituted. While net zero carbon emissions represent a worth goal, the existing production, necessary inputs and distribution channels and services exist to serve end demand.

When prices for important current commodities, like oil and gas, are disrupted through natural supply interruptions, due to poor weather, lack of available resources, or war disruption, there are follow on effects in the markets for many goods and services that are not easily fixed.

What happens, in the real economy, is that development of new supply is rarely frictionless. The supply of cloud computing services may appear frictionless, but even a large increase in capacity would be subject to availability of computer hardware, network equipment, skilled personnel, and suitable construction sites for any new facility.

Conditions are way more complicated in relation to long lead time items like copper mines. The general rule of thumb is that it takes at least five years and typically ten to fifteen years to take a new resource discovery into a permitted, constructed and fully operating mine.

When we create client expectations, for the self-interested purpose of fund marketing, that are at odds with the time constants and delays typical of the real world the result is predictable.

Clients will be disappointed, and the measures taken to deflect attention from the failure to properly set expectations, will likely translate into rear-guard political action and cover-ups.

That is where I think we have gotten today with ESG.

Everybody would like to see the energy transition completed quickly, at least possible harm to the global economy and environment. However, in my life experience, reason is rarely the dominant force of political action.

Politics, in practice, will likely solve for how to please the most people through imposing whatever harm may seem justified on whomever is seen to be the most popular culprit for any present problem.

That is politics, and I am not naive enough to try and change it.

However, I will state that investors are not obliged to behave in this destructive fashion. It is the job of the professional capital allocator to weigh carefully the likely benefit versus harm of any particular investment decision. Since I am nearly sixty years old, I do not, personally view such ethical decisions as being susceptible of any formulaic solution. Furthermore, I think that any decision I might make would not, as a general matter, be in full accord with the decision another investor might make. Acknowledging that we each view the world in a different way, and bring different perspective, knowledge and life experience, I doubt very much that one could ever arrive at a systematic consensus to only do this and never do that.

Perhaps, when I was younger, I might have considered complex questions to be best served with simple answers. I no longer think or feel that way. The implicit social conundrum, that is posed by manifestly irreconcilable difference of opinion, is solved, for me, in practice, via the social institution of the marketplace. It is an old saw of market wisdom to state:

Markets run on difference of opinion

For every seller there is a buyer, and outside of markets for contraband, which we do outlaw, there is a place for buyers and sellers to legitimately meet and conduct trade.

Of course, some today contend that fossil fuels are properly contraband.

That is a point of view some will hold, but it is not a legal fact. On that basis, there remains a marketplace for fossil fuels, and clear demand for them. Given that a fossil fueled car, ship, aircraft, or truck can only run on said fuel, and not electricity, we clearly need to replace the current capital stock with new capital stock. That has always been my avowed strategy to combat climate change from carbon emissions. The investment task is simply framed:

Identify, at the margin, which component of capital stock to replace first, and then next. Once committed to this path, rinse and then repeat.

You will appreciate, from that statement, that I am not much impressed by overt political statements of the need to punish this or that economic actor for their alleged crimes.

There are people who bought fossil fueled cars who need gasoline, or diesel, to get to work. I may not be overtly politically minded, but I am not stupid. Case in point:

The current fleet of Australian fire trucks and ambulances run on fossil fuels.

That is simply a fact, and so I cannot countenance statements of policy as absolutes. That will change one day, but it has not changed (yet). That is the crux of the eternal dillemma.

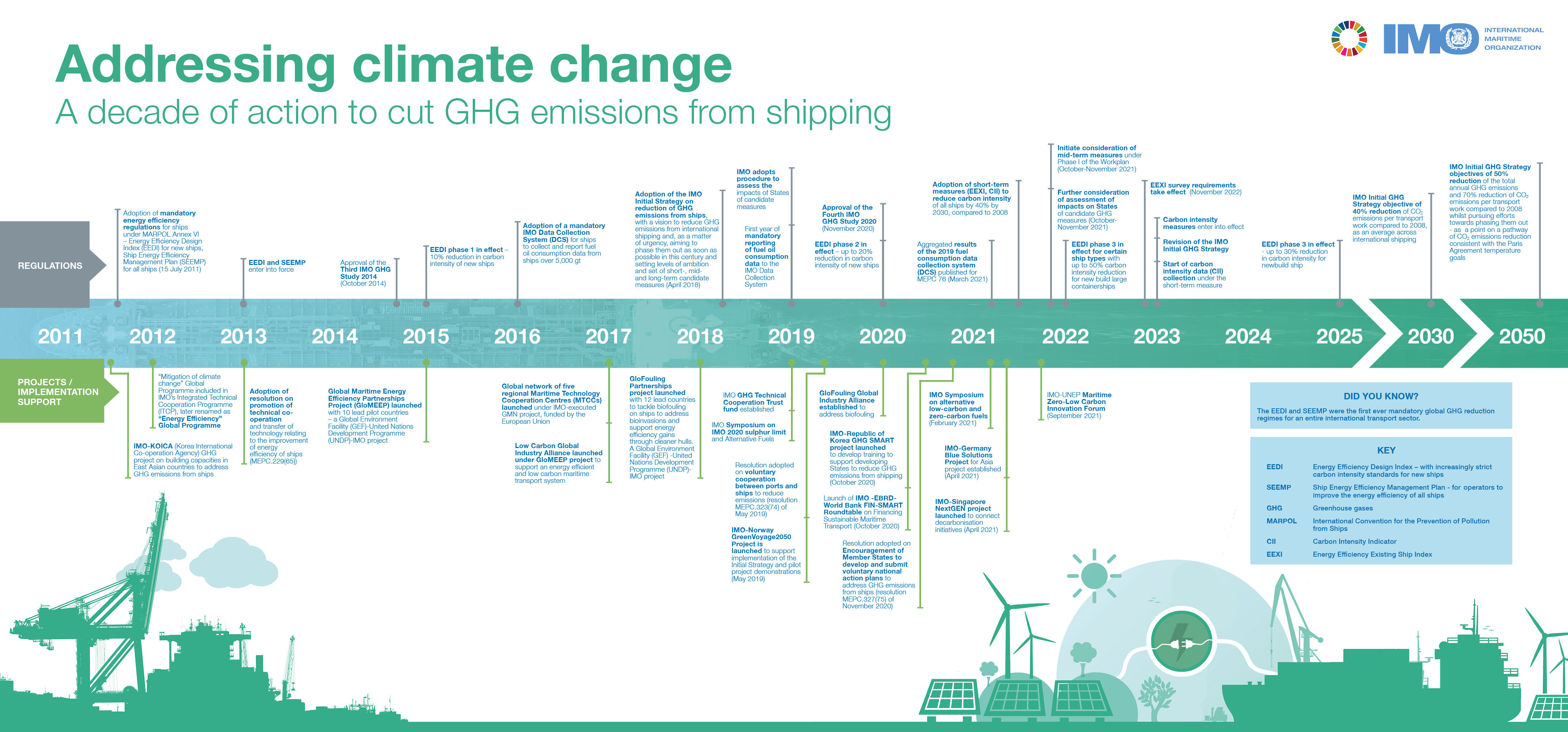

We do know that electric trucks are coming, and already sold in small numbers. We can see that alternative fueled shipping will arrive shortly. However, we do not yet know, for sure, if the new fleet will choose hydrogen or ammonia in preference to the current lowest carbon choice, which is not diesel or fuel oil, but Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). The capital allocation to make such changes happen does take time, and not simply due to industry reticence. Ships take some years to hit the water from the initial order. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is intending to announce their new fuel standards imminently, but until then owners and operators of shipping fleets will not commit to new orders. These are properly their decisions since it is their capital at risk in that industry. Shipping is a notoriously cyclical industry.

_small.jpg)

Some may take the view that such a complex task of greening the global shipping fleet is susceptible of a simple solution:

Just do "X" now and compel anyone who does not agree with you to do it.

That approach might conceivably work, in a place like China.

However, the IMO is not called "International" for nothing, since the vast bulk of the oceans of this world are not the sovereign territory or claim of any nation. There is no one party to hold to account, of national origin, but only the consensus offered by international conventions.

Some people might contend that, in offering up this viewpoint, that I am simply another fossil relic of a bygone era who cannot bear to think that the future may not look like my past. That could be a fair line of argument to run, but I am ready with a natural riposte.

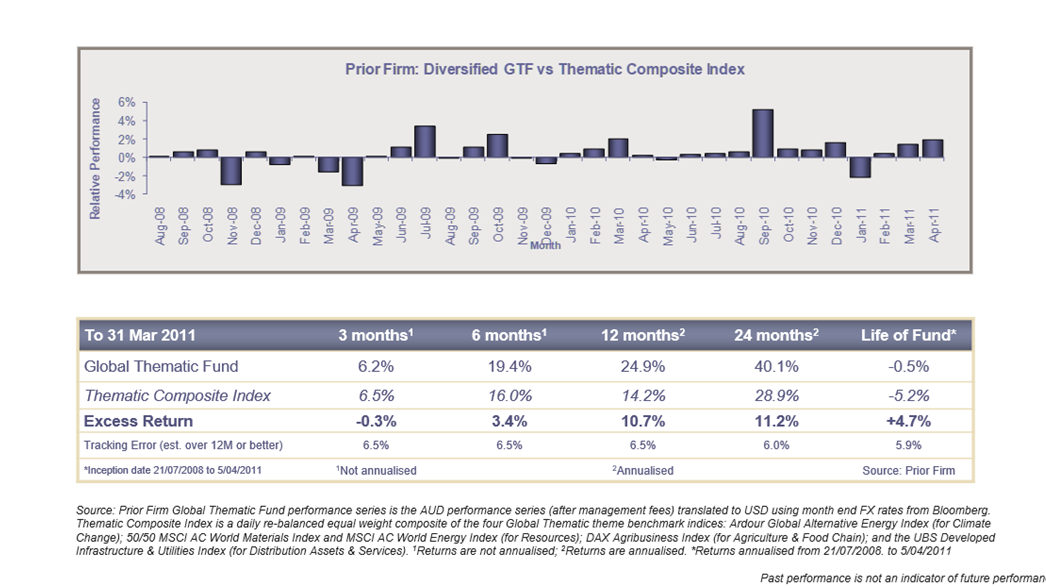

Here is the prior track record of the Global Thematic Fund (GTF) my team and I ran during the period from July-2008 through March-2011 at a major Australian investment bank.

That was a diversified global equity strategy focused on what we might now term the obvious areas of supply chain security that would likely prove prominent during the energy transition:

- Global Food and Agriculture

- Global Resources and Energy

- Global Climate Change Mitigation Technology

- Global Infrastructure

When we voluntarily shuttered that fund in April 2011 it was number one in the then Global Mercer Survey for equity fund performance for Australian fund offerings.

You may ask why anybody would shut down a number one performing strategy.

The reasoning was rational and had two components:

- Our back-office costs were so high that breakeven was well north of $200M AUM

- The Australian Superannuation Funds we spoke to did not believe in the strategy

Needless to say, the second factor dominated in our decision making, although I would mention that the first factor remains a severe impediment for new funds in Australia.

The central problem we faced, in running a climate change-oriented fund, in the period before ESG rose to prominence, was the lack of belief among institutional investors that the issue of climate change warranted any new or different approach to investment.

In many ways, I don't think that the outcome would be greatly different today.

Our entire investment strategy consisted of pursuing a resolute focus on:

Capital investment to replace old GHG-generating plant with new plant of lower emissions. In simple terms, replace fossil fuel engines with electric.

This is not how the investment markets have shown a preference to engage with the issue.

Practical considerations of engineering, lead times for replacement, capex versus opex, and sundry considerations of optimal cost-benefit analysis make for dreary marketing.

History has demonstrated the more profitable funds management direction to follow

- Carbon accounting that is based on actuarial assumptions and not field measurement

- Carbon credit trade in receipts for a promise to have done something to abate emissions.

- Fund names with "sustainable" in the marketing material and lots of ESG metrics

The result is a world where most of the focus is on sustainability ratings, badges to show who is on the program versus who is off the program, and copious happy face marketing shots.

As a manifest loser in the marketing wars, whose investment team simply went about the job of figuring out which oddly named firm like Spirax-Sarco SPX.L or Sika SIK.S, might actually lay claim to being both a good investment, and a contributor to positive outcomes, I am happy to admit that we were bested by a bunch of fund marketers with much sexier PowerPoint.

In all honesty, I don't think any of this will change.

The ultimate client is more susceptible to a fantastic promise than the voice of reason. Reality can be a big downer when marketing any fund product.

This is why books, such as the Wall-Street expose by Fred Schwed Jr. remain classics.

As portfolio managers, because I think that is to whom this missive is addressed, we all know full well the Faustian Bargain that one hatched with marketing to actually have a business. It is an essential feature of successful business to goose the product promise from "interesting" into the realm of the "irresistible". That is how business works.

However, there is a real world out there, with a growing mismatch between what society at large actually needs and what many seem prepared to stick in their investment portfolios.

It is nice to have more trees, but only new capital plant, with lower emissions, will serve to deliver what society needs while enabling retirement of old plant that we no longer need.

To demonstrate, very clearly, just why I do not think present ESG frameworks will cut any mustard, I will share one small, but I hope cogent, example of how it all goes so wrong.

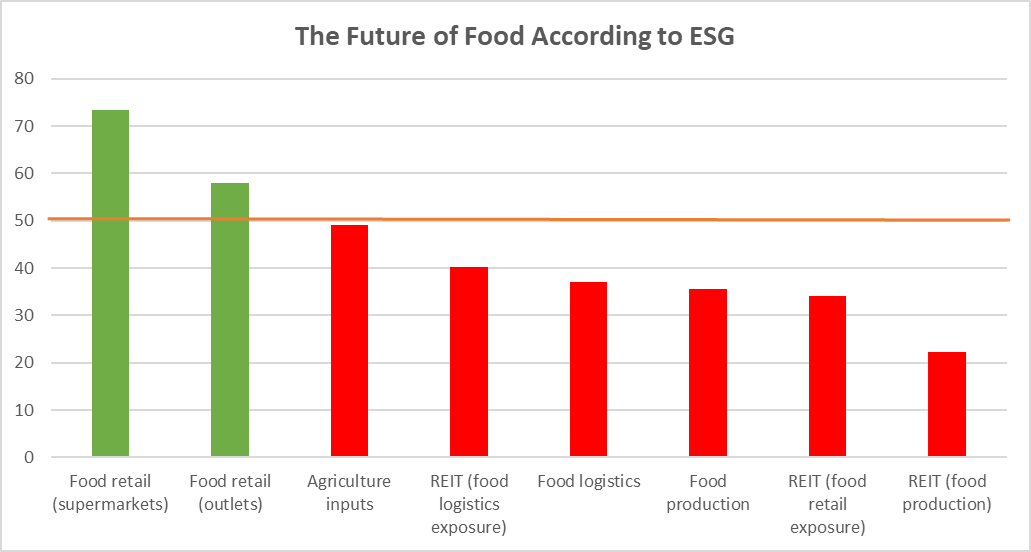

Like any right-thinking portfolio management team, we at Jevons Global use quantitative ESG signals to help shape our deliberations of what stocks to accept and which stocks to reject when constructing investment portfolios. It is not the whole process but supports it.

I am not going to embarrass our data vendor by stating from which source I got the array of numbers I am about to share. However, I am prepared to state that I think the problem I am about to point out is actually universal to pretty much all current schemes. It is a very simple consequence of the age-old Biblical warning (Matthew 6:24):

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one and love the other; or else he will hold to the one and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and Mammon.

Yea... that is old skool heavy, yes. However, I will reframe it shortly in a more prosaic sense.

The problem is pretty simple.

I construct portfolios whose performance is measured to an agreed benchmark.

That is the purely financial question of the investment rate of return.

However, I am also measured according to how my portfolios look when assessed according to ESG data, which consists of three numbers, each measured from 0 (bad) to 100 (good).

- E for Environment score

- S for Social score

- G for Governance score.

These numbers are now readily provided, on the basis of corporate survey responses, and then collated and standardized to remove any apparent "hidden biases". It is a global industry that is widely used by funds managers, using a credible range of global data vendors.

There is no reason to doubt the good intentions or diligence of the relevant data vendors.

The problem arises with standardization and the hidden biases inherent in that process.

This is a process like we all endured in school, when the teachers would mark exam papers, and then adjust all of the marks to fit the requisite "bell curve". When you perform this statistical adjustment, you are basically working out the average, or typical score, of any one identified group (ideally homogeneous - like all Grade 9 level students), and then adjusting all scores up, or down, so that they have the same average as, say, all Grade 10 students.

This is done universally, across all global industries, to reshape the raw ESG scores so that they do not have overt biases that would cause capital to flow one way. Obviously, if enthusiasm for sustainable investing were to cause under-investment in certain areas, then market prices for the requisite product or service would soon adjust to reflect shortage or surplus.

Of course, some people might contend that you should put zero capital into new fossil fuels while others might suggest that you put some. The standardization process that is inherent in the attempt to avoid overt bias is, of itself, prone to the allegation that it is biased, somehow.

ESG cannot serve the two masters of two different standardized averages.

This is pretty obvious for the example of fossil fuels.

However, some of these biases, that are created by standardization, can be both pernicious and subtle. They can lurk in a deeply hidden fashion, only to surface when probed closely.

Here is a striking example I came across this week in completing a client request.

The context is pretty simple. Jevons Global specializes in thematic analysis of the value chain for a particular category of good or service: from food through minerals to semiconductors.

This is an investment philosophy that my team and I pioneered in the days of our now defunct Global Thematic Fund (GTF). It is the reason, I maintain, why my relatively small portfolio team was able to outperform much larger and better resourced global investment teams.

However, this secret sauce was also the key reason why we had trouble persuading pension funds that our process innovation was one they should adopt. In simple terms, we had a view of the world that rested on regrouping stocks into what we thought were more natural ways to view and analyze what each firm did in relationship to its suppliers and customers. Our entire view of the world was supply-chain oriented from the get-go. This was not how our prospects thought about the world, then, or even now. The sectors were sacrosanct. They had been crafted atop a mountain, and borne down to the masses as a stone tablet:

The Global Industry Classification System (GICS)

Woe betides any heathen who would question the Wisdom of GICS!!!

Such is the stuff of investment heresy.

Bollocks to That!

I have always thought of GICS as a thoroughly stupid sector system.

You take companies that buy and sell to each-other and cast them into totally separate siloes for analysis, with two different analysts who are measured according to how well they don't ever talk to one another about which firm has the upper hand in pricing negotiations.

It is a deeply flawed and stupid system invented by people who never visited the real world.

Now you can see why I get SO frustrated by ESG, as practiced today.

Look more closely at Figure 3 above on the right and proper measure of which parts of the food supply chain are "blessed" (green) by being above average students of ESG (>50), and those parts of the food supply chain that are "cursed" (red) by being those persistently low scoring, disruptive, and dare-I-say-it reprobate, backsliding, perma-failure students (<50).

As I remarked to my earnestly well-intentioned, but long-suffering client:

It looks like we should allocate all capital to supermarkets and fast-food outlets. What we should avoid, at all costs, is any food production.

You can think that I am joking, which I am in that wry sad fashion of recognizing just how deeply and thoroughly broken the present global funds management industry really is.

Needless to say, this is not actually a joke.

This is an objective reality of a deeply flawed ESG scoring and rating system.

It is only because Jevons Global explicitly focuses on supply chain analysis that we are ever clearly confronted with the hidden biases of the GICS system of classification.

Since that is the global standard, it is clearly my firm who is wrong.

I am the errant backsliding, sustainably bad actor, who has failed to understand the key and essential message of the future of global food:

Let the punters starve in an empty super-market with no lighting and no food on the shelves. This is the Way. There shall be no further food production!

Evern better. When they get to the local KFC, offer them spring water, and no fried chicken.

You get my drift. This is a broken approach to sustainable investing.

Leadership demands that we call out this nonsense for what it is.

Our clients are not as stupid as we seem to be (I mean, us funds managers)

They know that when they signed up to be "sustainable investors" it was not their goal to wear sackcloth and ashes, live in a cave, and forage by flaming-bush light for nuts and berries.

So end-eth the ESG lesson.

Hopefully, we can move past the present Greek Tragedy into a world more sensible.

Image Credit: Donald Cooper / Licensed photo from Alamy Stock Photo

The chorus in BACCHAI by Euripides at the Olivier Theatre, National Theatre (NT), London SE1 17/05/2002 translated by Colin Teevan music: Harrison Birtwistle design: Alison Chitty lighting: Peter Mumford movement: Marie-Gabrielle Rotie director: Peter Hall

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire. Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics