Why rising oil prices are deflationary, not inflationary

There are two major themes I’ve been writing about over the past six months:

1. The Fed will crush the US economy with its tight monetary policy, leading to a big fall in inflation.

2. Energy prices are in a structural bull market and you should use any correction to buy or build a position.

This led to a client asking how I can expect inflation to fall while being bullish on energy.

It’s a good question. The answer is complex, but in this wire I’ll try to simplify as much as possible (for me as much as you) to get my point across.

And my point is this:

In a rising rate environment, where monetary policy turns restrictive, rising energy prices are deflationary, not inflationary.

Now, before you rush to the comments section telling me what an idiot I am, hear me out…

I know inflation is the topic of the day. The latest reading from the US, for the month of September, shows inflation remaining stubbornly high at 8.2%, or 6.6% when stripping out food and energy.

But as the great Milton Friedman wrote, monetary policy acts with long and variable lags. It can take a year or longer for the effects of monetary tightening to show up in the inflation numbers. That being the case, the inflation numbers you’re seeing today are still the product of near zero interest rates back in 2021.

The Fed only started raising rates in March this year. So expect CPI readings to fall sharply into 2023. But that’s a topic for another day.

For now, let’s get back to the deflationary impact of rising energy prices.

Let’s start with a thought experiment…

Imagine you have a budget of $100 a week for food and fuel. There is no additional supply of dollars coming into your ‘system’ (household) to help you deal with price rises.

Let’s say you normally spend $20 a week on fuel and $80 on food. Following an oil price shock, due to a big fall in supply, the price rises significantly. You cut down on all non-essential travel, but you still find yourself having to spent $30 a week on fuel.

Unfortunately, there is no additional supply of dollars coming in to help you manage this supply-induced price shock. So you have to cut back on food (maybe eating out) to maintain essential travel.

What makes this especially difficult is that those businesses exposed to higher prices try to pass those costs on. They show up in higher food prices. Which means your $70 per week stretches even less than it used to.

So you’re cutting down spending in dollar terms, but the higher prices (yes, inflation, but bear with me) mean you must buy less. So economy wide, production levels fall, even though nominal spending remains the same.

Those companies see that demand is falling, and that they’re producing less. They realise that they can’t pass on costs without hitting demand, so look to cut their own costs to keep prices down. Or they may be more willing to absorb the costs themselves and take a hit to margins and profitability.

The point I’m trying to get across here is that after the initial passing on of higher energy costs (inflation) it get much harder to continue doing so.

Why?

The crucial factor here is the household budget. The weekly supply of $100 isn’t growing.

This is where tight monetary policy comes into play.

US money supply has stopping growing

In the US right now, money supply has stopped growing. In fact, it’s now contracting.

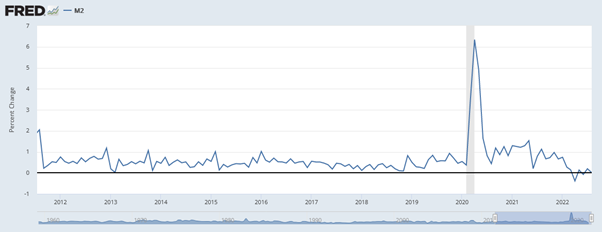

If we take M2 as a rough proxy for US money supply, you can see in the chart below (monthly frequency, seasonally adjusted) that it fell into negative territory in April and basically hasn’t grown since.

In this environment (assuming it persists) it is very hard to get an inflationary outcome.

That’s because the US monetary system is no longer creating a growing supply of dollars.

If production is recovering thanks to an easing of the supply side issues caused by the pandemic, what does that mean for prices, if there is no growth in the money supply?

All other things equal, it means prices will fall per unit of new supply.

Now, all other things are never equal. I’m just trying to illustrate a point. But basically, all the inflation you’ve seen and are still seeing is a result of the surge in the money supply in 2020 and 2021.

It went into cryptos and tech stocks first, and then into the real economy. But now the Fed is reducing the money supply, or at least no longer growing it.

If money supply growth was still humming along at a decent clip, I’d be very worried about inflation becoming a longer term problem. Because after newly created money goes from the stock market into the real economy, the next step is for it to go into wages. Then prices rise more, and wages follow again.

The good old ‘wage/price spiral’.

And while you have seen a rise in wages, it has lagged the rise in prices, effectively cutting real incomes.

Rising oil prices absorb scarce dollars

Coming back to oil and energy, if prices rise, it effectively absorbs more of the money supply. That leaves less for other goods and services, or wages, meaning prices fall.

So that is how rising oil prices can act as a deflationary force on the economy.

To be clear, I’m not betting that oil prices will rise in an environment of shrinking money supply. As you can see from the chart, M2 rarely dips into negative territory. The last time it did so was December 2009.

If the current tight monetary regime continues, most US dollar denominated assets will struggle.

I just think energy will do relatively better, given the structural supply issues. And when demand growth returns, the sector should do very well.

But I thought it was important to illustrate the point that just because a crucial economic input like oil goes up in price, it doesn’t automatically lead to inflation.

For that to happen, you need supportive monetary aggregates, like a growing supply of money.

And with the Fed hell bent on crushing the inflation it caused from its 2020/21 policy of monetizing government spending, it think the money supply will struggle to grow for some time yet.

Where did the semiconductor shortage go?

One last point on inflation. Remember how back in 2021 there was a shortage of computer chips? The car industry, among others, was impacted heavily, as manufacturers waited for chips before they could sell the final product.

It was a problem of excess demand and restricted supply. It caused a buying frenzy in semiconductor stocks in late 2021.

But as you can see in the chart below, the PHLX Semiconductor Index, known as the SOX, it down nearly 50% from its peak.

Very, very few people would have predicted such an outcome in late 2021.

But that’s how quickly things can change.

As we head into late 2022, my guess is that we’ll be having a very different conversation regarding inflation by this time next year.

What that means for the stock market and your portfolio is a discussion for another wire.

Until then…

3 topics