Why super and growth assets like shares have to be seen as long-term investments

This is an update of a note I wrote last November, but after the recent plunge in shares and the associated 10% or so loss in balanced growth superannuation funds through the March quarter, it’s particularly relevant now. When share markets plunge as they did into March the standard questions are: What caused the fall? What’s the outlook? And what does it mean for superannuation? The correct answer to the latter should be “nothing really, as super is a long-term investment and share market volatility is normal.” This may sound like marketing spin. But, except for those who are into trading or are close to or in retirement - shares and super really are long-term investments.

Super funds, growth assets & compound interest

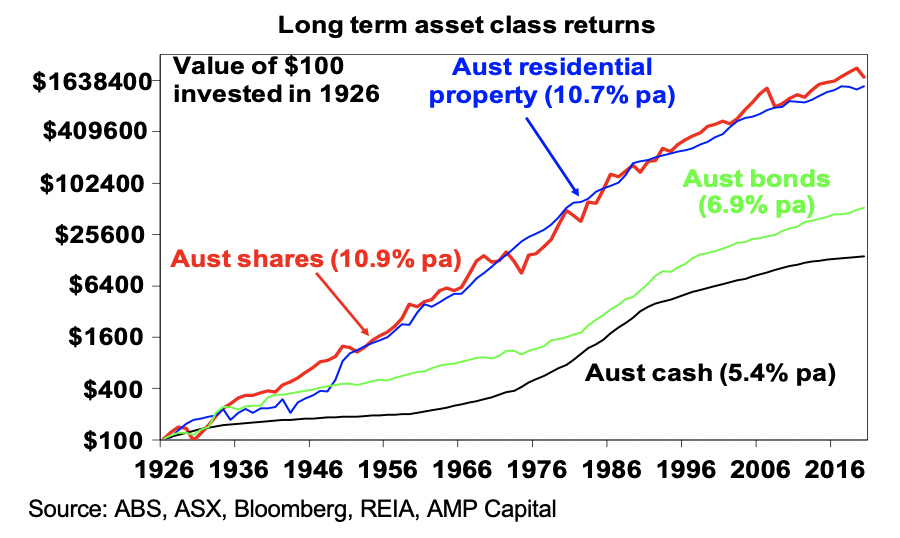

Superannuation is aimed (within reason) at providing maximum (risk-adjusted) funds for use in retirement. So typical Australian super funds have a bias towards shares and other growth assets that grow in value with the economy, particularly for younger members, and some exposure to defensive assets like bonds and cash to avoid excessive short-term volatility. These approaches aim to make the most of the power of compound interest which sees returns build on returns over time. The next chart shows the value of a $100 investment in Australian cash, bonds, shares and residential property from 1926 assuming any interest, dividends and rents is reinvested along the way.

As return series for commercial property and infrastructure only go back a few decades I have used residential property as a proxy. Over the period shown since 1926 cash has returned 5.4% per annum, bonds 6.9% pa, property 10.7% pa and shares 10.9% pa. Because shares and property provide higher returns over long periods the value of an investment in them compounds to a much higher amount over long periods. So, it makes sense to have a decent exposure to them when saving for retirement. The higher return from shares and growth assets reflects compensation for the greater risk in investing in them – in terms of capital loss, volatility and illiquidity.

But investors don’t have 90 years?

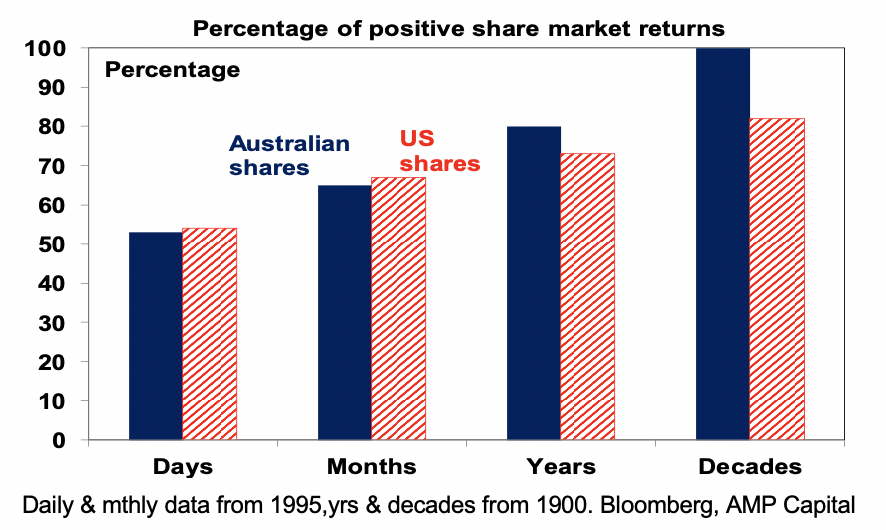

But while the above chart covered more than 90 years of returns, our natural tendency is to think very short term. Particularly so in times of uncertainty like now. And this is where the problem starts. On a day to day basis shares are down almost as much as they are up. See the next chart. So, day to day, it’s pretty much a coin toss as to whether you will get good news or bad on shares. But if you just look monthly and allow for dividends, the historical experience suggests you will only get bad news around a third of the time. If you go out to once a decade, positive returns have been seen 100% of the time for Australian shares and 82% for US shares. So while it’s hard given the bombardment of financial news these days it makes sense to look at your returns less because then you are more likely to get positive returns and less likely to make rash decisions based on short term bad news.

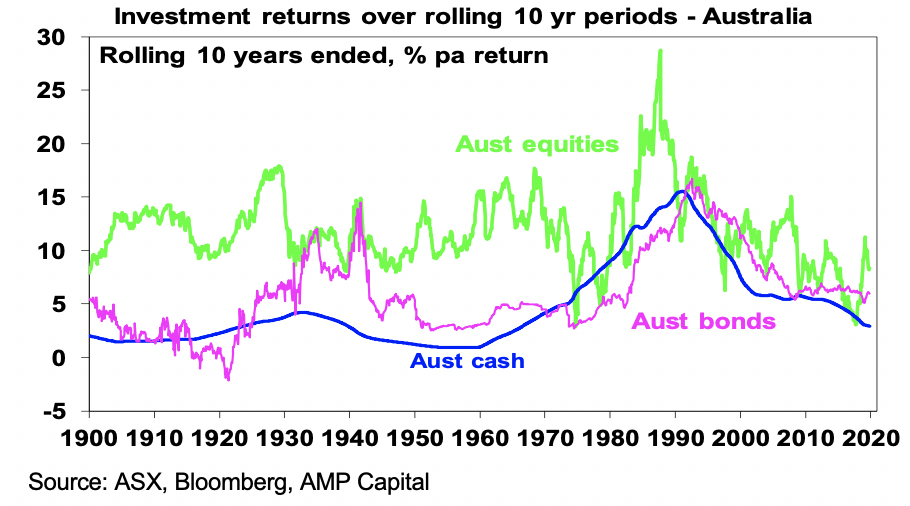

This can also be demonstrated in the following charts. On a rolling 12 month ended basis the returns from shares bounce around all over the place compared to the relative stability of cash (and bonds). See the next chart.

However, over rolling ten-year periods, shares have invariably outperformed, although there have been some periods where returns from bonds and cash have done better, albeit briefly.

Pushing the horizon out to rolling 20-year returns has almost always seen shares do even better, although a surge in cash and bond returns from the 1970s/1980s has seen the gap narrow. Over rolling 40-year periods – the working years of a typical person – shares have always done better.

This is all consistent with the basic proposition that higher short-term volatility from shares - often reflecting exposure to periods of falling profits and a risk that companies go bust - is rewarded over the long term with higher returns.

But why not try and time short-term market moves?

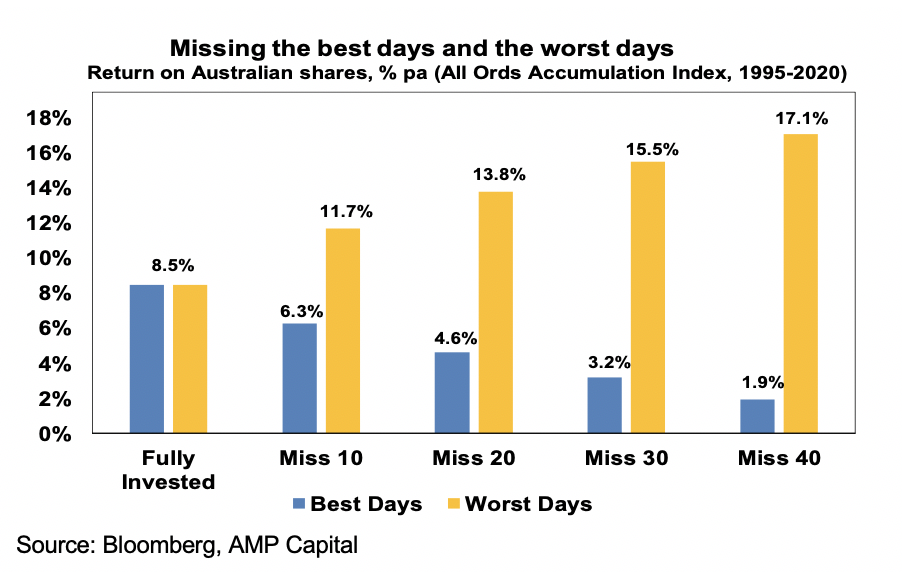

The temptation to do this is immense. With the benefit of hindsight many swings in markets like the tech boom and bust, the GFC and maybe in the years ahead the current episode look inevitable and hence forecastable and so it’s natural to think “why not give it a go?” by switching between say cash and shares within your super to anticipate market moves. Fair enough if you have a process and put the effort in. But without a tried and tested market timing process, trying to time the market is difficult. A good way to demonstrate this is with a comparison of returns if an investor is fully invested in shares versus missing out on the best (or worst) days. The next chart shows that if you were fully invested in Australian shares from January 1995, you would have returned 8.5% pa (with dividends but not allowing for franking credits, tax and fees).

If by trying to time the market you avoided the 10 worst days (yellow bars), you would have boosted your return to 11.7% pa. And if you avoided the 40 worst days, it would have been boosted to 17.1% pa! But this is not easy as many investors only get out after the bad returns have occurred, just in time to miss some of the best days. For example, if by trying to time the market you miss the 10 best days (blue bars), the return falls to 6.3% pa. If you miss the 40 best days, it drops to just 1.9% pa.

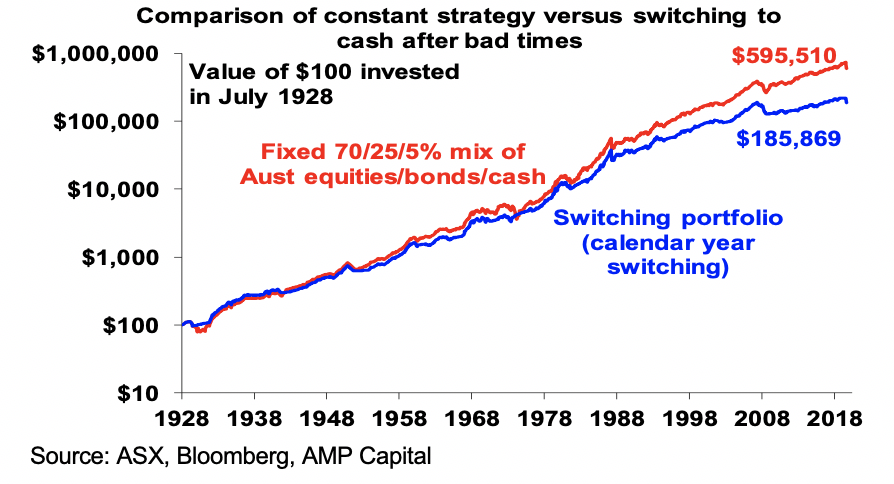

The following chart shows the difficulties of short-term timing in another way. It shows the cumulative return of two portfolios.

- A fixed balanced mix of 70 per cent Australian equities, 25 per cent bonds and five per cent cash;

- A “switching portfolio” which starts off with the above but moves 100 per cent into cash after any negative calendar year in the balanced portfolio and doesn't move back until after the balanced portfolio has a calendar year of positive returns. We have assumed a two-month lag.

Over the long run the switching portfolio produces

an average return of 8.6% pa versus 9.9% pa for the balanced mix. From a $100

investment in 1928 the switching portfolio would have grown to $185,869

compared to $595,510 for the constant mix.

Key messages

First, while shares and other growth assets go through periods of short-term underperformance relative to bonds and cash, they provide superior returns over the long term. As such, it makes sense that superannuation has a high exposure to them.

Second, switching to cash after a bad patch is not the best strategy for maximising retirement savings and wealth over time as it locks in the loss with no hope of recovery.

Third, the less you look at your investments the less you will be disappointed. This reduces the chance of selling at the wrong time or adopting an overly cautious stance.

The best approach is to simply recognise that super and investing in shares is a long-term investment. The exceptions to this are if you are really into putting in the effort to getting short-term trading right and/or you are close to, or in, retirement.

4 topics