Why Telstra is a sell

I usually don’t write about specific stocks here at Livewire.

But it’s something I do all the time for members of my Fat Tail Investment Advisory service.

I recently recommended a sell on Telstra, a stock that had been in the portfolio since the dark days of 2018. We banked a 50% gain on the investment. Not eye-popping by any means, but reasonable given the market’s performance over that timeframe.

In this wire, I wanted to explain my reasoning for selling now. Not that I have a deep understanding of the threats and opportunities faced by the telco. Rather, I understand the simple concept of company valuation, and the all-important risk/reward trade-off.

And, as I’ll show you, that trade off is beginning to skew towards more risk and less reward for Telstra shareholders.

Here’s the high level reasoning, then I’ll drill down to specifics…

Telstra – indeed most quality defensives – are now in favour. When markets are uncertain, capital gravitates towards certainty.

Sure, operationally Telstra has performed very well in recent years. And it has a well defined future path via its T25 strategy.

So it’s not surprising to see capital flow into Australia’s dominant telco.

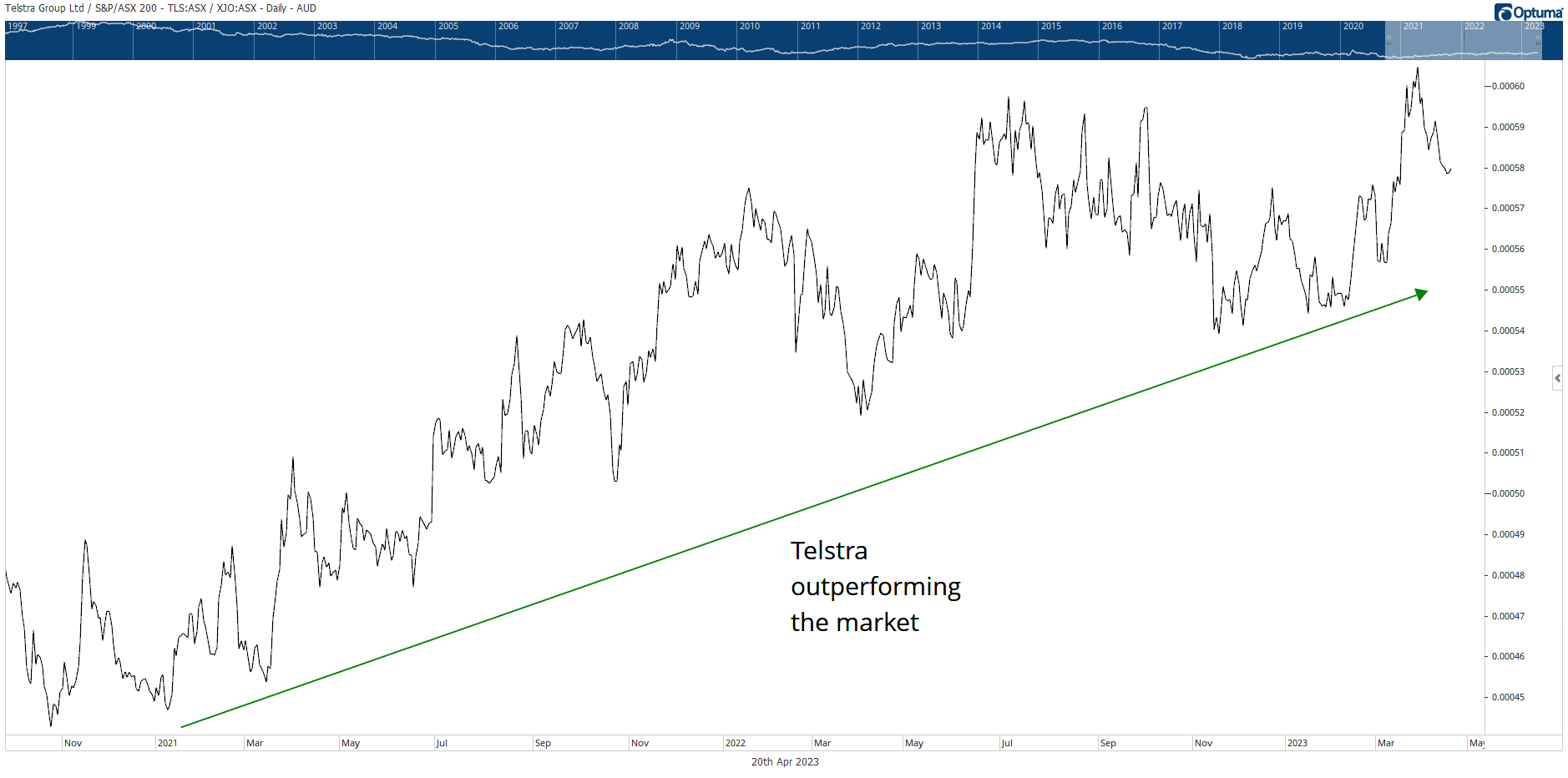

As a result, Telstra has outperformed the market in recent years. The chart below shows Telstra’s share price relative to the ASX200. As you can see, it’s been moving steadily higher, denoting outperformance.

Could that continue?

Sure. Trends can last for a long time. But I think the probability of continued outperformance is getting lower. And it all comes down to valuation…

Valuation is in the eye of the beholder

Valuation is a tricky, slippery subject. I can give you whatever valuation you want. It just requires a change of inputs.

One of the most important inputs into any valuation model, and one rarely discussed, is the ‘discount rate', or 'required rate of return'.

The discount rate is the rate at which future cash flows are discounted back to today's dollars to give you a present value.

Another way to think of it is the rate of return a long-term business owner is happy with to make on an investment. It is this required rate of return that will determine the price an owner is willing to pay for a business. Dividends, plus reinvested earnings (that increase the balance sheet value of the company), should equate to the discount rate over the long term.

Of course, the stock market can deliver more or less than your discount rate depending on the short-term whims of investors in driving share prices up or down. But using a conservative discount rate (I usually use 8% for larger companies) gives you a good starting point and ensures you’re not paying too much.

Needless to say, using an 8% discount rate on Telstra’s future expected cashflows provides a much lower valuation than the current price.

Let me explain…

Telstra pays out nearly 100% of earnings as a dividend. It therefore reinvests little shareholder capital back into the business. This is not a ‘growth’ company.

So, with nearly all earnings paid out as a dividend, what is the dividend yield?

Based on 2024 dividend estimates of 18 cents per share, and using the share price of the time of writing of $4.28, Telstra’s dividend yield is around 4.2%.

If the discount rate, or required rate of return, is a combination of dividends paid and reinvested earnings, the implied discount rate for Telstra is closer to its dividend yield of 4.2%. In other words, the long term business owner, assuming they paid the current price to gain ownership, will earn around 4.2% per annum on the investment.

Not great, is it?

Telstra’s implied return is getting thin

In reality, the implied return is a little higher than that. Without getting too detailed, this is because Telstra’s free cashflows are (usually) higher than its accounting profit. And you should value Telstra based on it’s free cashflow generation, not its accounting profit.

The company doesn’t pay out ALL its free cashflow as a dividend. Again, not usually. In FY22 it paid out 57% of free cashflows as a dividend, but in the first half of FY23, it paid out 139%!

So it’s tricky estimating value. Which is why the market is just a confluence of a million different opinions. Mine is just one of them.

But let’s assume Telstra will sustainably pay out 80% of free cashflows as a dividend and reinvest the remaining 20%. It therefore should have a small ‘growth premium’ embedded in its share price.

Putting this assumption into my model suggests the implied long term rate of return you’re getting from Telstra at these prices is around 6.5%.

Not a disaster, but not overly attractive for an equity investment.

For some perspective, Telstra recently issued a bond with a coupon of 4.9%, maturing in March 2028. I think I’d prefer that return rather than buy the equity (with the capital risk that that entails) for an extra 160 basis points per annum.

Of course, anything can happen to improve the outlook for Telstra’s equity investors. Asset sales or some sort of deal with the NBN could change the picture. Who knows?

But what I do know is that when your implied future returns start to look thin, it’s time to look elsewhere.

That’s why my starting point is 8%. Now, I know that may not seem much different from my estimate of Telstra’s implied return of 6.5%.

But small changes in the discount rate (the implied return) have big impacts on valuations.

A basic example will suffice…

$1 million discounted by 5% gives a capitalised value of $20 million ($1m divided by 5%). Increase the discount rate to 10% and you halve the capitalised value. ($1m/10%).

Assuming an 8% discount rate for Telstra (and assuming an 80% dividend payout ratio) gives me an estimate of value of $3.26.

I want to be clear this only an estimate. There is no such thing as ‘intrinsic value’. There are only estimates of value, and they all depend on the inputs. The discount rate is an important input, but so are things like future earnings estimates, the profitability of those earnings, and dividend policy.

With that as a caveat, this estimate of Telstra’s value says to me that investors are too complacent. They’re putting too high a price on ‘earnings certainty’. They feel comforted hiding in big defensives and getting a decent dividend while they wait.

That may feel good while the broader market struggles. But when everyone feels comfortable with an investment, it’s a sure sign of a lack of compelling value.

Enjoyed this piece? Check out my publication for more

To find out which energy stocks I'm currently recommending, or if you’re interested in staying up-to-date with my latest analysis on the Australian market, click this link now to get access to my publication The Fat Tail Investment Advisory.

1 topic

1 stock mentioned