Why the everyday investor should consider adding this asset class to their portfolio

For the last two decades, private equity has yielded increased returns for investors by capitalising on opportunities to harness substantial growth and enhance the efficiency of established businesses. Yet for many investors accessing these opportunities has been beyond reach. Not anymore.

Private equity has attracted trillions of dollars for a simple reason. For the last two decades, this asset class has yielded increased returns for investors by capitalising on opportunities to harness substantial growth and enhance the efficiency of established businesses.

Yet for many investors accessing these opportunities have been beyond reach. Most private equity investments have barriers to entry, often requiring large initial investments, multi-year financial commitments, illiquidity and limited transparency.

But there is a way to participate in this asset class - listed private equity. By investing in the stocks of publicly listed companies that specialise in private equity, investors can potentially gain access to the realm of private equity while also avoiding the drawbacks associated with the asset class.

Private Equity

Put simply, private equity is the ownership or interest in a corporate entity that is not publicly listed. There are different types of private equity investment. It can involve taking a stake in a growing business, making direct loans to a business, or it can be taking control of a company either through outright purchase or through obtaining a controlling equity interest (buyout). Private equity provides capital to nurture expansion, new products or restructuring with the goal of unlocking greater value for investors.

And private equity is growing.

According to consultancy firm Bain & Company, “the number of US public companies has declined by about a third over the last 25 years, and the remaining pool is dominated by a handful of large tech firms that hold disproportionate sway over the indexes. That makes it increasingly difficult to find adequate diversification in the public markets. Private market returns, meanwhile, are outpacing public returns over every time horizon, while alternative funds provide access to the broad global economy and the fullest range of asset classes. These advantages explain why private markets continue to grow relative to the public markets.“

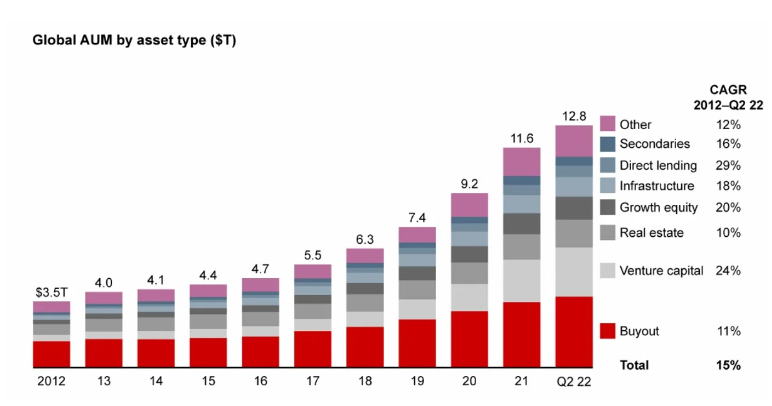

While buyout remains the industry’s largest asset class, a variety of others have been growing at double-digit rates as you can see from the chart below:

Chart 1: Buyout and venture capital continue to expand

The difficulty of access

Traditionally, direct investments in private companies and in private equity funds require:

- large capital outlays,

- long lockup periods, and

- investors taking a concentrated, illiquid exposure to a small number of private companies – which are often leveraged.

It is that last point that has been the subject to debate recently. The two most important points to remember about liquidity are:

- Its definition – a liquid investment can be readily acquired and converted to cash.

- The impact on price – a liquid investment can be bought or sold at a fair value without a significant premium or discount to its fair value. An illiquid investment may need to be sold at a discount to be readily converted to cash.

The illiquidity premium of private equity

By investing in private equity, large superannuation funds are potentially being ‘rewarded’ for illiquidity. They are locking up their investment for a long period of time, in the hope that their private equity investment comes to fruition.

The illiquidity premium is the additional returns an investor can capture from locking their money up for a longer duration than if it was sitting in cash or public markets.

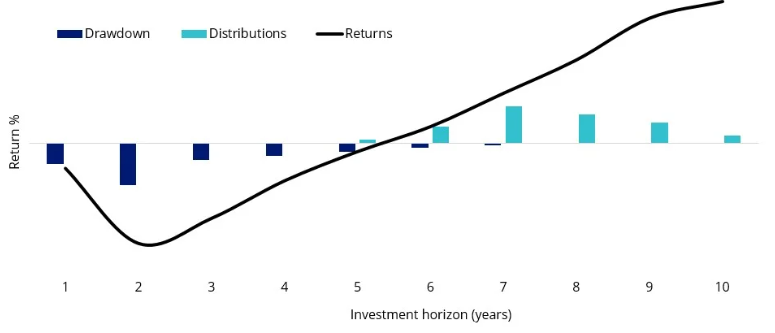

The J-curve, shown below, illustrates this.

Chart 2: The private equity J-Curve

You can see in the chart above, investors, while making significant investments in private equity typically endure losses during the early years of the investment, as the business establishes, or re-establishes, itself (blue drawdowns in the chart above). At this stage you would say the investment is illiquid, it’s unlikely an investor could sell their stake at a fair valuation, if at all.

Hopefully, the business matures and then requires less capital. Cash flows increase and eventually, it starts to return income to investors represented above as distributions. Over this time, the value of the private equity investment also increases. The return line is sloping upwards. In the hypothetical example above, by year 10, the investment may be more liquid, in other words, someone might be willing to pay close to fair value for the asset.

This doesn't mean there are no ways to exit a position in the private markets at any time, but investors often can’t get out quickly and will need to sell via a secondary market to a buyer willing to buy their asset. This contrasts with listed securities that can be easily bought and sold on an exchange.

Investing in private equity, while potentially rewarding, is risky and the recent market volatility has bought this to the fore for Australia’s largest superannuation funds.

Risks of private equity investing

The increasing allocation by large super funds into unlisted private equity assets is problematic for two main reasons:

- Price disclosure and valuation, there is no price visibility for members of the fund over the value of private equity assets held. Valuations are subjective and infrequent.

- Liquidity risks for those funds making high allocations to illiquid assets.

Price disclosure and valuations

The first problem with allocations to unlisted private equity is that prices are not easily observable, valuations are opaque, subjective and infrequent. The lack of market prices can result in opaque valuations, which can misstate investment or fund values. As a result, members may never know the value of unlisted assets in their super funds. For example, overvaluing a private equity investment could potentially have an overstated impact on investment returns.

The venture capital sector of private equity has been in the news of late, with discussion about the valuations of Australian start-up Canva. Many large Australian super funds have benefited from the company’s meteoric rise from a small IT firm in Perth to a multibillion-dollar enterprise. However, recently the company’s valuations have taken a hit. The recent sale by Venture Capital fund, Blackbird of some of its stake in Canva to US investors at a valuation of US$25.5 billion, is down by 36.25% from a peak of US$40 billion in September 2021.

As reported in The Australian, Canva’s valuation has seesawed over the past two years with Investor T. Rowe Price reportedly marking down its stake by 68% in June. Franklin Templeton also cut its valuation by 10% earlier this year, after lifting it by 22% in 2022.

Another is Klarna, a Swedish buy-now-pay-later firm which some super funds directly or indirectly hold. The privately held Swedish fintech, whose valuation was slashed from US$46 billion to US$6.7 billion last year, reported its annual net loss had grown to SKr10.4 billion ($1 billion), a 47% increase from 2021. As the underwhelming initial public offerings of Uber and WeWork show, the case is not isolated.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) undertook an unlisted asset valuation thematic review in 2021 which found superannuation fund’s revaluation frameworks need improvement. The findings included that board engagement was often limited, and, some trustees relied overly on external parties. The regulator has called upon super fund trustees to improve the frequency and methodology used in unlisted valuations.

Despite these risks, the lure of private equity remains, but there is no reason you should not be able to access this asset class.

Listed private equity

Listed private equity companies, that trade publicly on exchanges around the world, gain their exposure to private equity either:

- directly, that is the company invests directly in private equity from its own balance sheet;

- indirectly, by investing into private equity funds; or

- they are the private equity managers themselves.

Listed private equity can provide investors with similar exposure to the benefits of unlisted investments in a more transparent, lower cost, and accessible way.

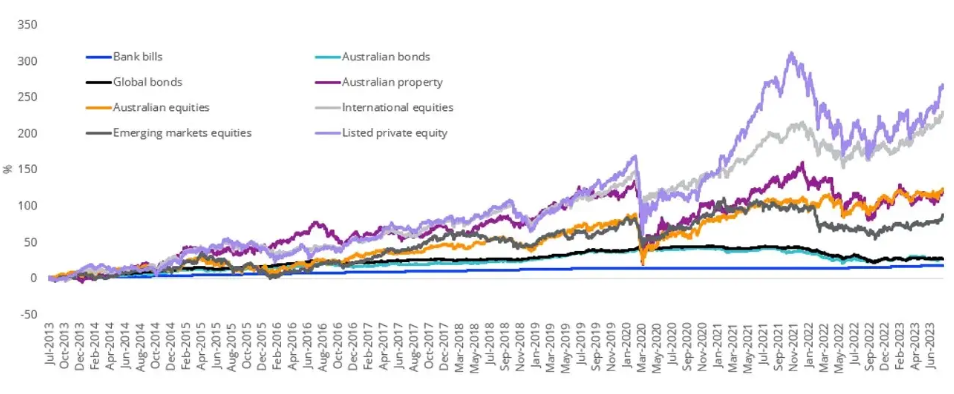

The LPX50 index, which includes the largest and most liquid 50 private equity companies giving investors exposure to venture, growth and buy-out opportunities. You can see from the chart below, why large institutions continue to invest in private equity.

Chart 3: 10-year hypothetical performance: The listed private equity index has outperformed other asset classes

VanEck’s Global Listed Private Equity ETF (ASX: GPEQ) tracks the LPX50. GPEQ is an Australian first, aiming to provide investors with private equity returns, but with share market liquidity.

GPEQ also aims to mitigate the effect of early year losses, noted in the J-Curve above, because the underlying portfolio comprises of a range of existing investments that are at different stages of maturity.

Traditionally only the largest institutions have had the resources to build a diversified portfolio of private equity funds. Now you can to. And it has the benefit of liquidity, being listed on ASX.

As always, we recommend you speak to your financial adviser or stock broker.

3 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 fund mentioned