Why the odds are now in favour of a softer landing

In the grand scheme of things, broader economic events significantly influence where asset values ultimately settle in the medium term. Regardless of their investment philosophy, history’s greatest investors have demonstrated a keen awareness of market cycles.

Benjamin Graham advocated for buying stocks when the overall market is trading at low prices. This typically happens during recessions. Graham’s most famous disciple, Warren Buffett, emphasises the importance of understanding market cycles, famously stating that anything written by Howard Marks, a cycle-conscious investor, goes straight to the top of his to-read list. Buffett's awareness of macroeconomic factors is well-documented, exemplified by his mid-2000s essay and bet against the US dollar. A closer examination of his investment strategy reveals that he tends to sell stocks when they perform well and increases his investments during economic downturns. While we believe that attractive investment opportunities should be pursued even on the brink of a recession, it is evident that broader economic cycles play a significant role in value-driven decision-making.

The pressing question today is whether we’re headed towards a soft landing or a recession. What’s unfolding?

The Shift in Economic Indicators

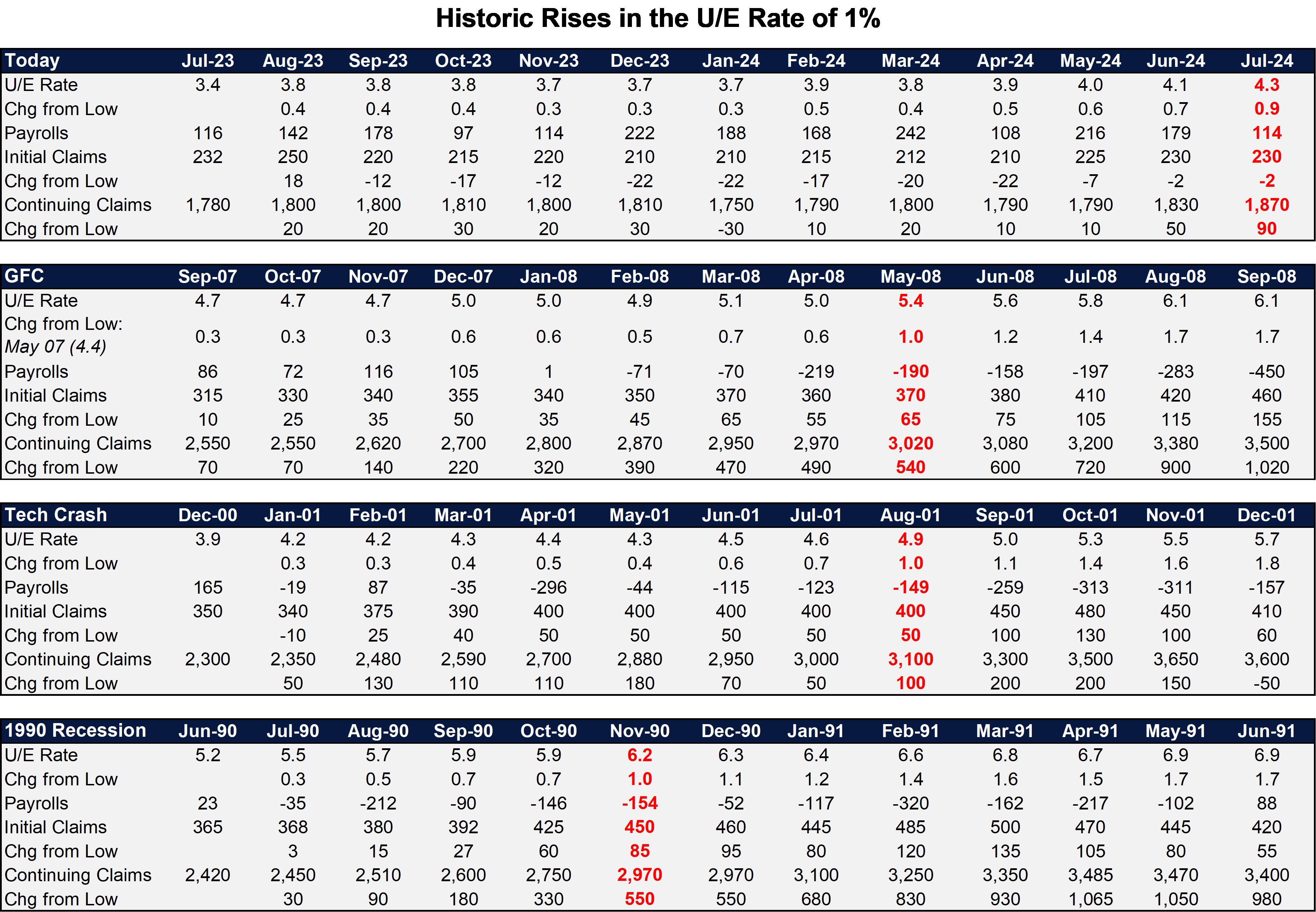

As we detailed in a recent note, the recent rise in the US unemployment rate has re-ignited concerns about a potential recession. Historically, whenever the unemployment rate has increased by around 1%, a recession has ensued, regardless of whether the central bank cuts interest rates or not.

While we believe it’d be unwise to exercise wilful blindness towards the possibility of a recession, will history repeat itself this time around? This economic cycle has been markedly different from previous ones, largely due to the excess savings accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic and the stimulative fiscal policies implemented thereafter. Will the labour market crack this time around? We've delved deeper into the situation, recognizing that it will significantly influence asset pricing in the next six months.

Understanding the Labor Market Dynamics

Firstly, the current rise in the unemployment rate differs from previous instances. In times past, by the time the unemployment rate had risen by 1%, the US economy was shedding jobs, and initial claims for unemployment insurance had seen a substantial increase. However, this time, that’s not really the case:

As the table above indicates, today’s 1% rise in the unemployment rate has not been accompanied by job losses, or a steep rise the number of people claiming unemployment insurance. While the labour market is clearly weakening, it hasn’t yet cracked. But will it crack in the near future?

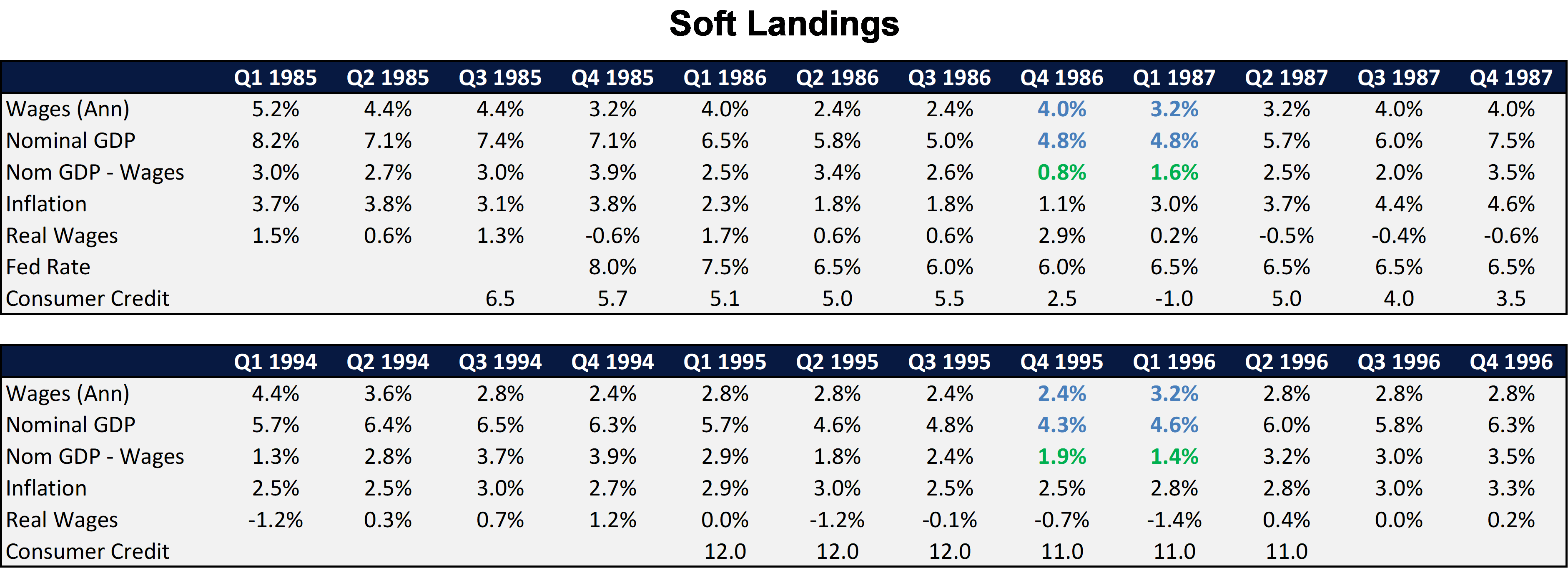

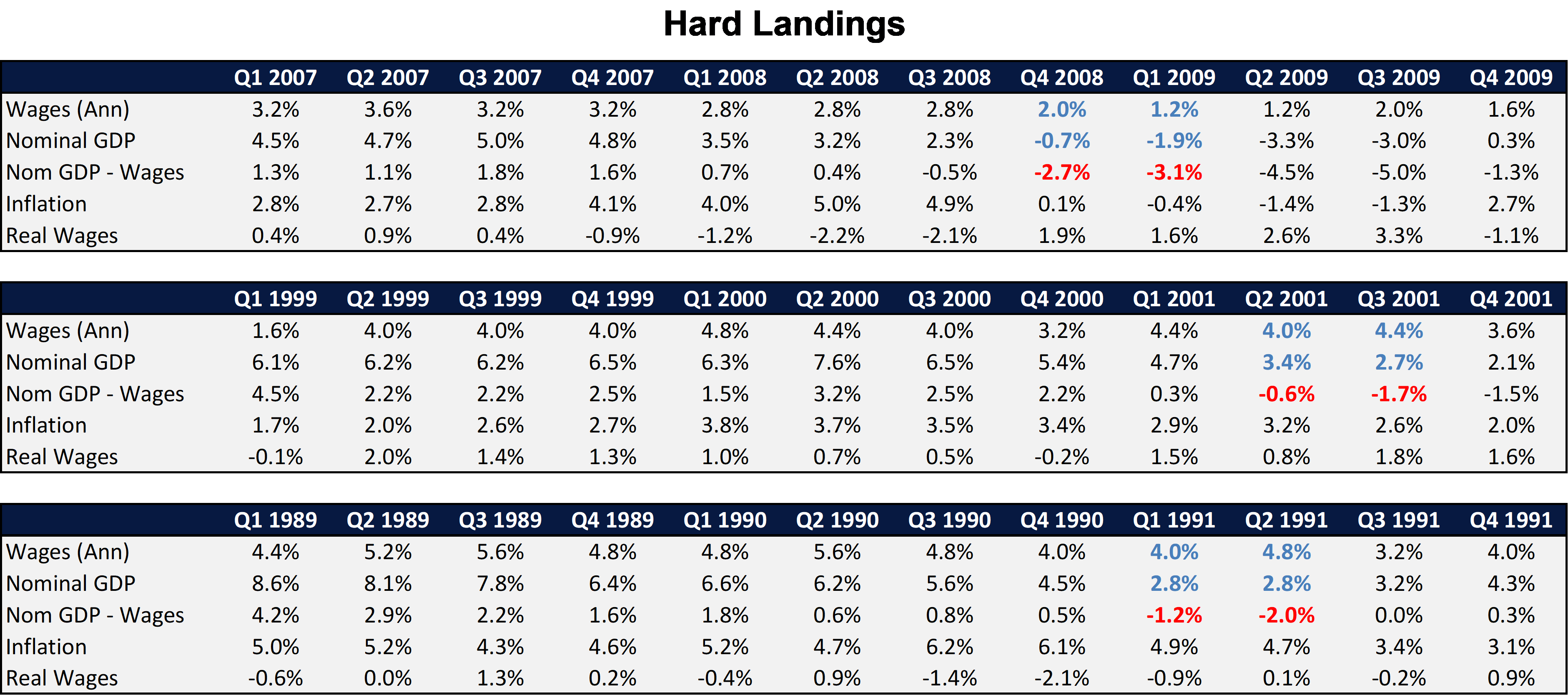

Historically, the key factor that differentiates soft landings (such as those in 1986-87 and 1995-96) from recessions is whether the labour market cracks or not. A common catalyst for a weakening labour market is when nominal spending growth falls below wage growth. When the increase in the amount of people who are willing to spend falls below the cost of holding onto staff, profits tend to shrink. Shrinking profits tend to lead businesses to reduce headcount.

In scenarios of soft landings, nominal GDP growth typically does not fall below wage growth:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis, Fawkes Capital Management

In recessions, the opposite is true:

The Role of Consumer Spending and Savings

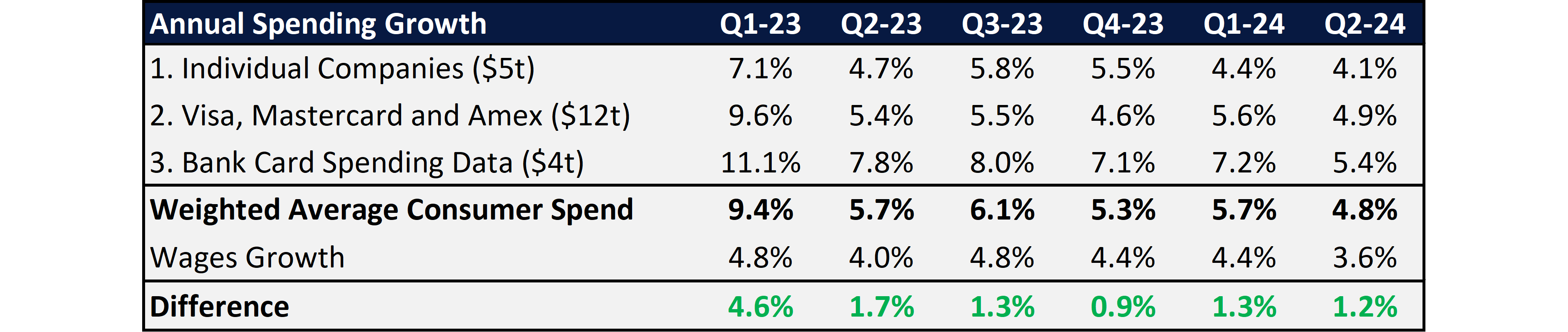

We measure nominal spending in three different ways to track how the consumer is faring. The first is by tracking the revenue growth of American business segments. Imperfectly, the 75 major companies we track account for around $5 trillion of annual American consumer spending, or roughly one-quarter of total consumer spending. After factoring in rent, mortgages, and utilities, these companies likely represent closer to half of discretionary spending.

The second method involves analysing the segment results of the three major debit and credit card issuers in the US – Mastercard, Visa, and American Express. Together, they process about $12 trillion in annual consumer spending, which represents approximately 60% of total U.S. consumer spending.

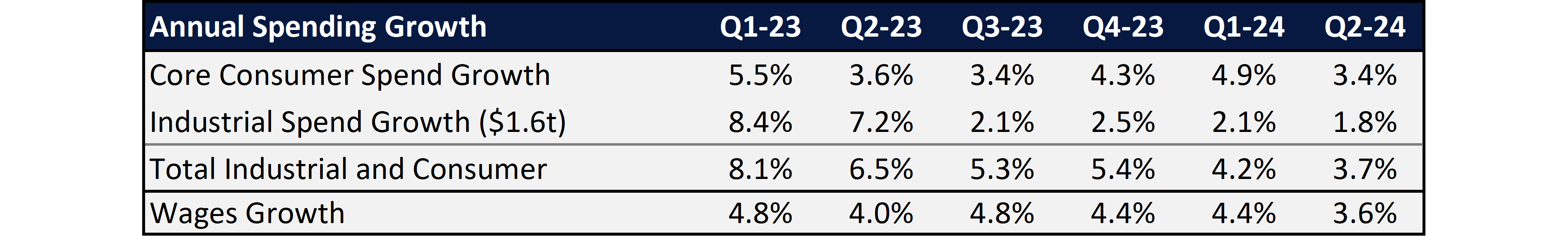

Finally, we triangulate these sources by looking at the payment volumes of the seven largest banks in the US, which combined account for around $4 trillion of annual spend. Based on these measures, nominal spending growth still outweighs wages growth by a healthy margin:

What also stands out to us is that the core consumer companies we track are experiencing relatively stable growth.

Many of the companies in this segment have guided towards only slightly slower nominal spending growth in the next quarter or two. Similarly, nominal spending growth at the major card issuers has only slightly decreased compared to a year ago.

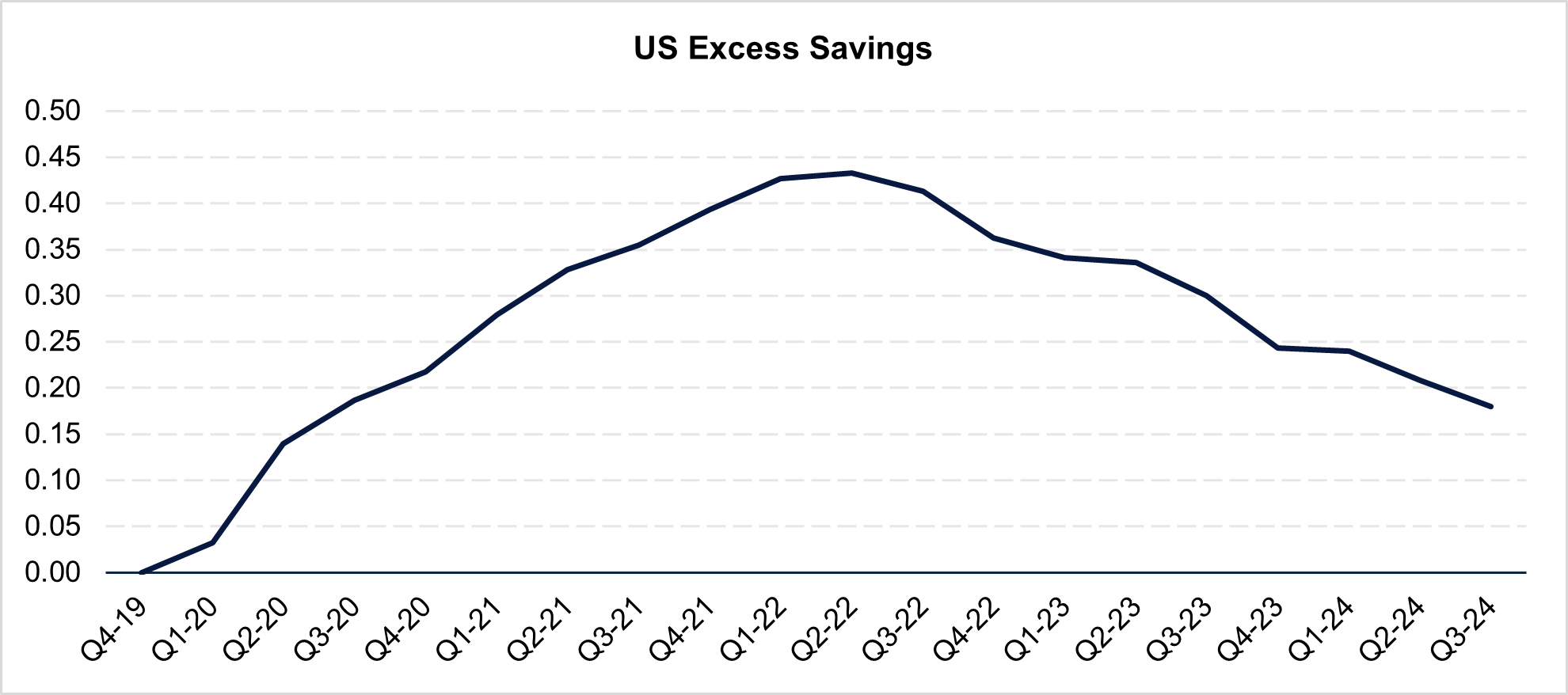

High interest rates are working their way through the system by reducing the spending power of those earning lower incomes. The Fed’s plan is working. Wages growth has normalised back to pre-Covid levels and nominal spending growth has also slowed. This combination of high interest rates, normalised wages growth and a pace of nominal spending growth that exceeds wages growth is producing the desired decline in consumer savings:

Now that excess savings have fallen to more reasonable levels, and inflation has returned to normal, the economy now desperately needs the Federal Reserve to cut rates. If the Fed cuts rates a little too slowly, then the weakest part of the economy, the industrial segment, may start to shed jobs. This job-shedding process would likely lead to a faster decline in nominal spending growth.

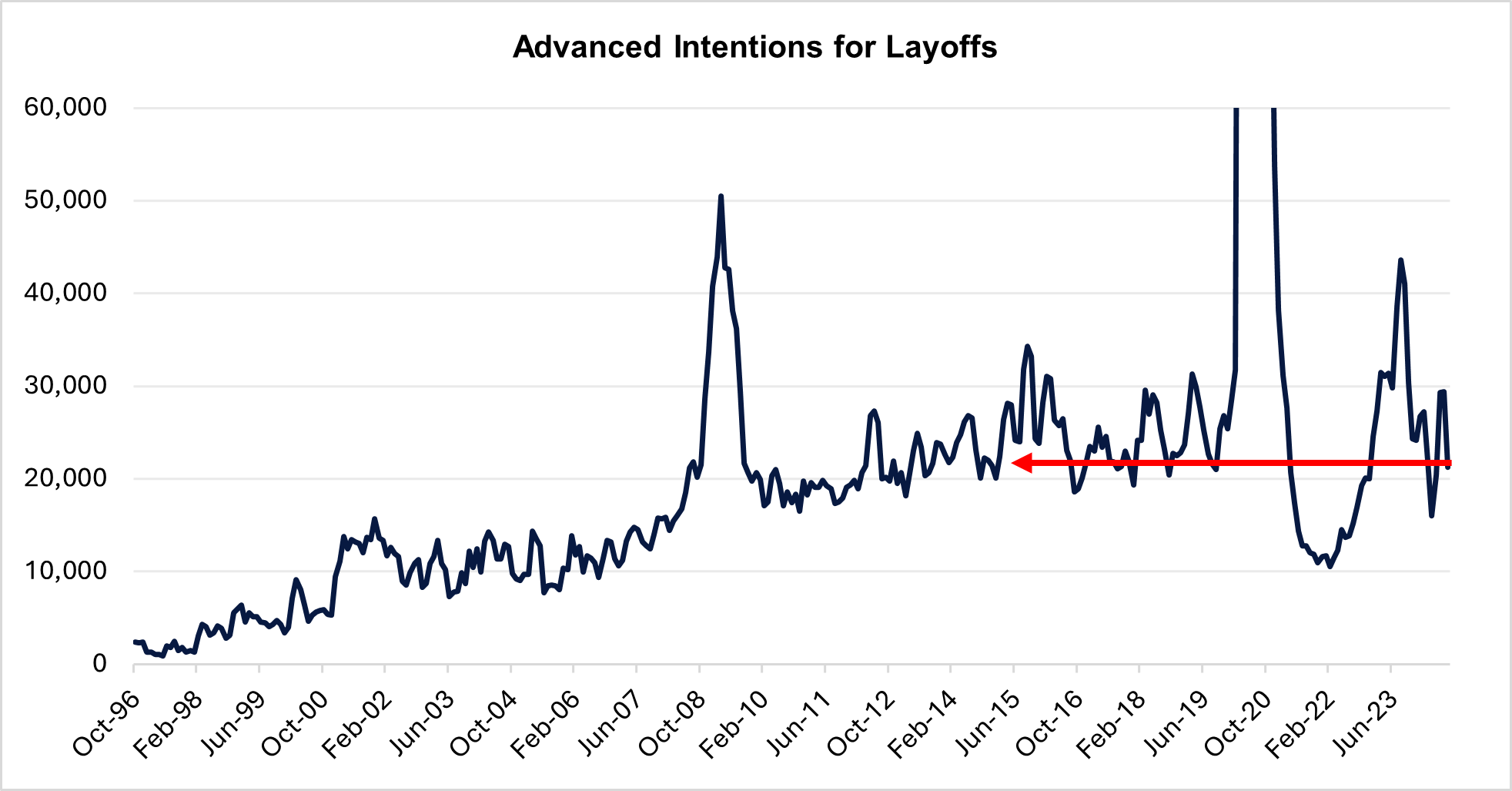

So far however, we’re not seeing it. We track advance intentions to lay off staff from various sources, and the data is yet to show anything to be worried about. Advanced intentions to lay off staff remain in the range of pre-Covid:

Nor are we observing any major layoffs from the companies that are hurting the most from our dataset. Ordinarily, before a recession, there will be a month or two where layoffs surge. After the normalisation of the labour market post-Covid, we’re yet to see that transpire.

Why a Recession is Less Likely Now

What do we assess the prospects of a soft landing going forward? After further analysis, we believe the chances remain quite favourable. While we previously noted an increased risk of recession, our additional research has led to two key insights.

- The decline in nominal spending growth is likely to be gradual due to two factors: (i) the excess savings within the system, which can sustain nominal spending growth above wage growth, and (ii) the forward guidance on sales growth we've observed so far in the third quarter.

- Many large companies that have been under the most pressure have either (i) already reduced their headcount or (ii) are unlikely to implement significant further job cuts.

Together, these factors suggest that the Federal Reserve may have enough time and a sufficient window to achieve a soft landing. Subsequent rate cuts could gradually ease the interest burden on consumers, helping to counterbalance the decline in savings.

However, we don’t entirely rule out the possibility of a recession. Unlike in 2022, nominal spending growth is now low enough that some sort of shock could tip the economy into contraction. Nonetheless, we now slightly revise our outlook to favour a soft landing over a recession at this stage.

We continue to closely monitor the situation. We have implemented tools to track the state of the labour market and layoffs in real-time. If circumstances change, we will adjust our portfolio positioning accordingly.

5 topics