Why the sell-off in equities is not far away

I was at University in the UK when Northern Rock was nationalised in 2007-08. As the Global Financial Crisis developed in unexpected ways, I took a job at a major retail bank in the City, in the risk management team contributing to scenario analysis. It was good experience. It confirmed that recessions tend to develop in non-linear paths, and new cracks can be discovered as the tide goes out.

The recent banking crisis need not result in the collapse of several more banks. Instead, I think a good old fashioned credit crunch in the US and Europe is now quite likely. And that is more likely than not going to result in a recession. This is a material shift from our previous view that the US would probably avoid recession in 2023.

But even though our view has changed, our portfolio positioning has not had to materially shift. In this wire, I explain why our view has changed, and why our portfolio remains overweight government bonds, funded out of equities.

The risk of a credit crunch has increased.

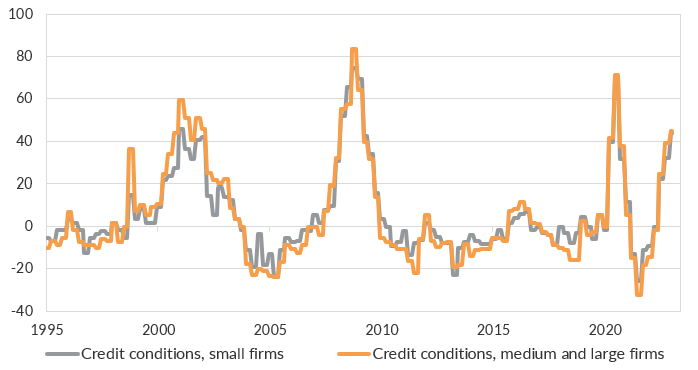

A credit crunch is a significant tightening of lending standards among banks. Loans become harder to get. And they become more costly. I think the recent turmoil in US and European banks makes a crunch much more likely.

The Fed has hiked rates aggressively. Credit standards were already tight as a result. But the banking crisis is almost certainly going to lead small and medium-size banks in the US to prioritise a healthy balance sheet over provision of loans.

Chart 1: Credit standards were already tight – and further tightening is likely.

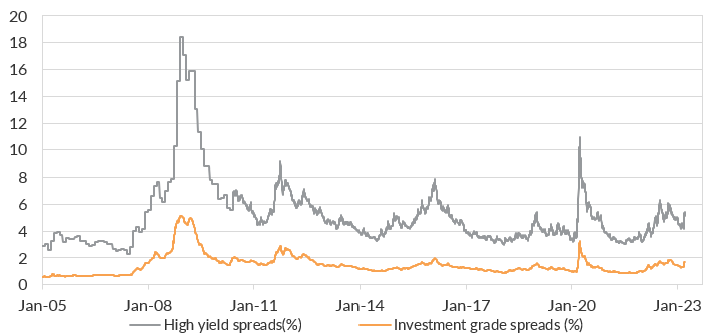

This tightening in standards will probably be met with a widening of credit spreads in the US corporate bond market. Already spreads have blown out. US corporates have mostly done a good job terming out their maturity profiles, but a sudden widening will add pressure to the sector, which I expect will be exacerbated by broader economic slowdown.

Chart 2: Credit spreads have already widened sharply, and could widen further.

The end of labour hoarding and a slowdown in inflation.

The US economy retained a fair bit of momentum in Q1 2023. The labour market in particular painted a positive picture. But a credit crunch will probably result in a sudden end to labour hoarding that has kept the labour market tight recently. The unemployment rate could move significantly higher in a short period of time.

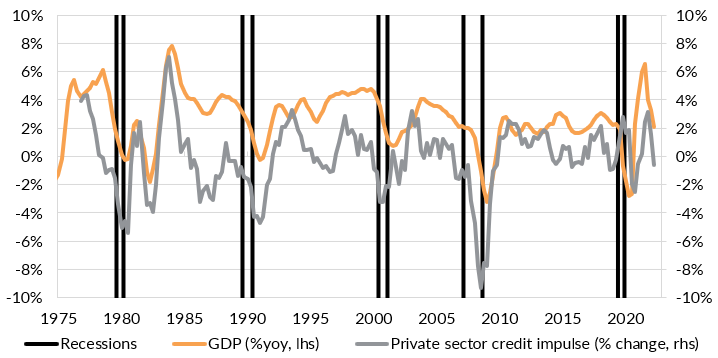

That loosening in the labour market alongside a credit crunch could spell an abrupt end to inflationary pressures that are already trending slower. Economic growth now looks more likely to tip into recession as the credit impulse slows to recessionary levels through 2023.

Chart 3: The credit impulse is slowing and a fall below -2% is probable - coinciding with a recession.

The Fed is almost done hiking.

I had been expecting the Fed to pause rate hikes shortly after the March rate hike. The recent developments make that even more likely, given the prospects for growth and inflation. Markets have moved to price a string of rate cuts by year-end, compared with a higher for longer scenario priced in early-March.

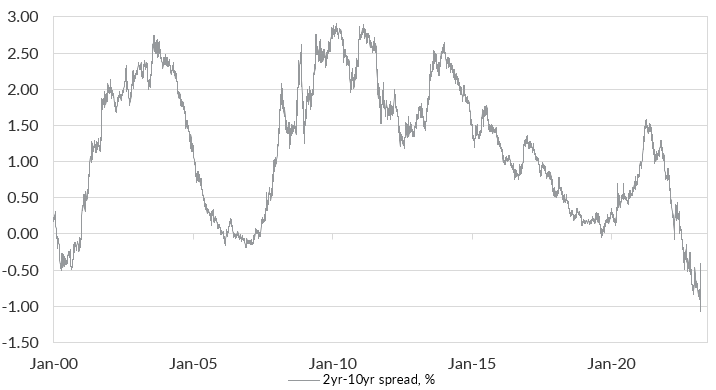

The appropriate focus is on the 2-year US Treasury yield. The 2-year yield climbed above 5.00% in early-March. It collapsed below 4.00% last week. Trading has been volatile as markets try to grasp the implications of the banking crisis.

Chart 4: The yield curve has started its normalisation.

The rally in front-end of the US curve has driven a remarkable amount of steepening in the US yield curve in a short period of time. Historically, the normalisation of the yield curve from deeply inverted to flat, then to steep has been a sign that the Fed has policy too restrictive for the real economy. It has tended to coincide with the beginning of a recession and a sell-off in equities. I think we are close to that point now.

Portfolios can keep moving in the same direction.

In November I wrote a wire that government bonds were the one asset that would do well across a range of scenarios. At that stage, longer-dated US Treasuries were yielding above 4.00%. Since then, our portfolios have been adding exposure to shorter-dated US Treasuries, particularly after the 2-year yield edged up above 5.00%.

This was funded out of equities. Not because US or Australian equities looked particularly bad value. We previously saw a lower probability of recession and thought equities represented around fair value. Instead, the move into government bonds was funded by equities to be aware of the downside risks posed by a recessionary scenario.

In the wake of the banking crisis, this directional move of adding exposure to short-dated government bonds as yields pop higher, and funding from equities, continues to make sense. It highlights the importance of scenario analysis, and considering assets that can perform well through a range of outcomes. And while markets remain extremely volatile in the near-term, I expect preparing portfolios for downside risk now will pay off later.

4 topics