Why timing is NOT everything

If we were sitting here 12 months ago, the RBA cash rate was 0.1%, Russia was yet to invade Ukraine, Scott Morrison was still Prime Minister, Australian house prices were still on the rise[1], coal prices had yet to really spike[2] and Bitcoin was hovering around AUD$60,000. If the past 12 months have taught us anything, it is that nothing lasts forever – things change.

A common phrase that is often at the forefront of our minds at NAOS during challenging times is that ‘nothing is ever as good or as bad as it seems’. Whilst this may provide a certain element of comfort in challenging times like now, the trick is to also remember this phrase during the far more exuberant times of say 2021. With the exception of the initial market reaction to COVID-19, for the best part of the past decade in the near zero interest rate environment, both TINA (there is no alternative) and FOMO (fear of missing out) have been substantial influences on global equity markets.

Despite that TINA and FOMO environment, most investors would have at least considered a scenario whereby interest rates would need to normalise upwards from ‘near zero’. Whilst this may have been obvious, the ‘when?’ and the ‘at what rate?’ had caught many off-guard. Put simply, there are factors and events which most simply cannot have predicted would subsequently influence the macroeconomic environment and caused such an abrupt shift away from TINA and FOMO over the past year. In our opinion, no matter how good or bad things may seem, picking the top & bottom of any economic cycle comes down to an element of speculation and is impossible to consistently replicate.

How about on the other extreme? To prove a point, imagine if timing was NOT your friend. Enter Bill Buffet. Unlike his namesake, you could describe Bill as being a ‘terrible’ investor. In fact, Bill may have the worst timing imaginable. Bill decided he wanted to continually allocate a portion of his savings generated over his career and invest it into equities. Bill’s approach was to invest in an ultra-low-cost index fund that directly mirrored the performance of the S&P500 Index. He chose this index as the ASX200 Index was not around at the time. Bill’s philosophy was that in the years he decided to invest, he would do so on January 1st.

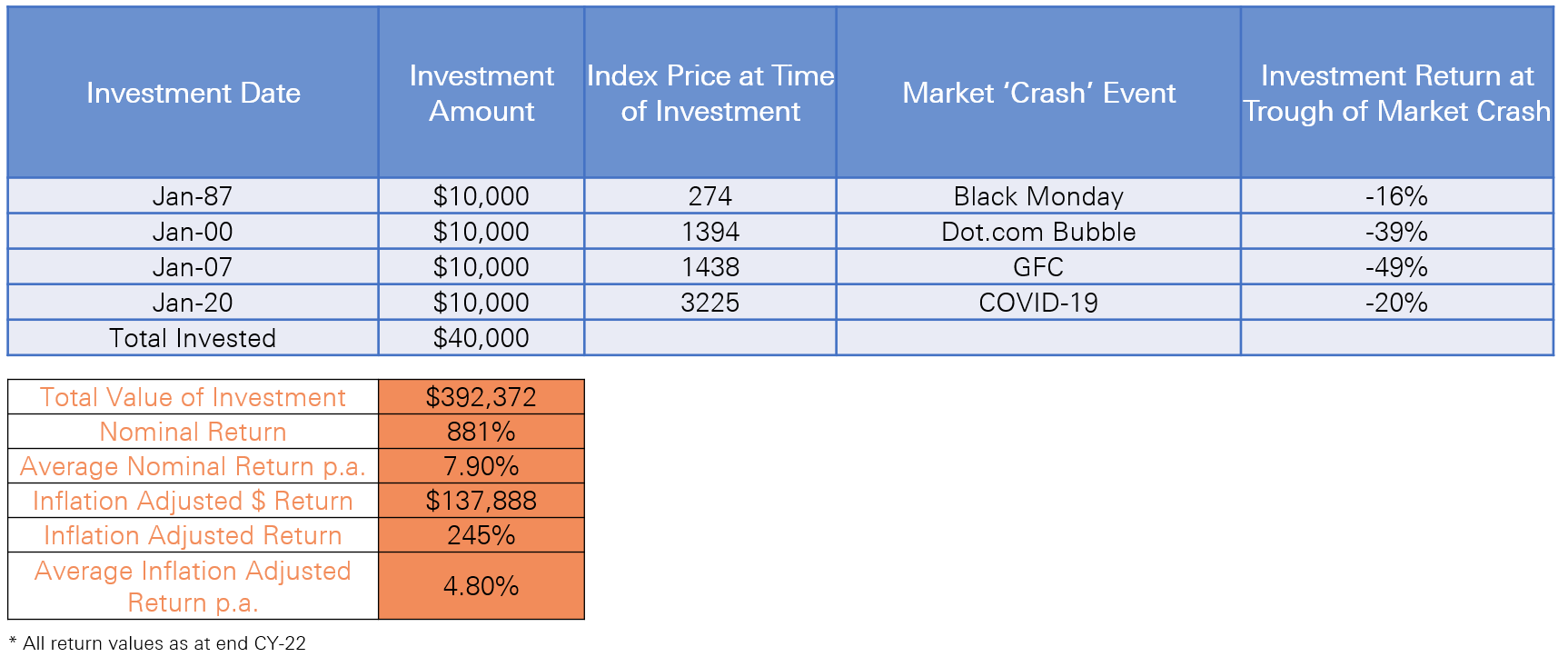

Unfortunately for Bill, he made his first investment back in 1987. As some may recall, that year the Black Monday crash occurred. Bill was so scarred from seeing the market crash overnight and the substantial paper loss suffered that he did nothing for a long time. He didn’t invest any further savings but more importantly he didn’t sell either. Over a decade later Bill finally felt comfortable enough to invest additional savings, but his timing was no better this time around. Again, with the pain of a substantial paper loss he was so scarred that Bill decided not to buy or sell for quite some period of time before joining in for the last of the pre-GFC bull market. Thirteen years on post the scarring GFC experience he once again invested just before the sudden COVID-19 induced market crash. Bill’s investment activity can be seen in the below table.

Table 1: The Investment History of Bill Buffett

Source: Yahoo Finance, OfficialData.Org, NAOS. S&P500 Index data is adjusted for dividends, capital gain distributions & stock splits. Returns assume all dividends are reinvested. All figures are in USD.

The example of Bill Buffet is a simplistic, theoretical one only, however in calculating his performance we can see that despite ‘terrible’ timing, Bill’s $40,000 investment is worth nearly 9x today and has generated a 4.8% p.a. average inflation adjusted return over this period of time. Perhaps Bill wasn’t such a ‘terrible’ investor after all, rather perhaps the key to his investment success was twofold:

1. Remaining invested despite market timing and not selling out after volatility occurs.

2. Despite the ups and downs the long-dated tenure of his investments has allowed compounding to thrive.

“Like so many other things in the investment world that might be tried on the basis of certitude and precision, waiting for the bottom to start buying is a great example of folly. So if targeting the bottom is wrong, when should you buy? The answer’s simple: when price is below intrinsic value.” Howard Marks

If we take the view that ‘nothing is ever as good or as bad as it seems’ and overlay it with the notion of being realistic and rational around the fact that arguably no one can actually time the market exactly right all the time, then we can become more grounded in our investment approach. From our perspective, this leads to the following conclusions:

- Understanding volatility and change are a part and parcel of investing.

- The importance of distinguishing between ‘speculating’ and ‘investing’.

- Focus on the long game to limit the short-term impact of timing & volatility and maximise the power of compounding.

At NAOS we aim to abide by the above mentioned conclusions to invest in quality emerging public and private companies with high conviction and a long-term approach.

5 topics