Why you can’t afford not to own government bonds

It’s all about certainty. People who argue that government bonds are a bad investment often base it on expectations of higher rates, higher inflation or simply that yields are too low. But these arguments miss one of the main reasons for owning government bonds: certainty.

In nominal terms, government bonds are the only asset where you know with absolute certainty the amount of income you will get over its life and how much it will be worth on maturity. For most other assets, you will only ever know the true return in arrears.

All the reasons stated for not owning bonds are valid, but they require a world economy that is growing strongly and we are far from that. If the level of interest rates is telling us anything, it’s that the world economy is weak and potentially getting weaker. Below I examine some of the reasons why owning bonds makes good sense in today’s climate.

Why our biases often lead us to the wrong conclusions

If interest markets are correct about the future, then the issue isn’t that bond yields are too low, it’s that expected returns in other asset classes are too high, unless you believe these asset classes now offer a higher premium above the risk-free return - unlikely in a low inflation and low growth environment.

Most return assumptions we use today were made when growth rates and inflation were generally higher and working-age populations were increasing in developed economies, particularly during the 1970s. This refusal to accept a lower overall return has led many investors to take greater risks on their defensive portfolios to compensate for persistent lower yields.

Investors tend to have an overconfidence bias. This can lead them to believe that the future can be more accurately predicted than is possible. We believe when making assumptions about the future that it’s better to think in terms of probabilities, which helps overcome this bias by assuming a wider range of potential outcomes and avoids relying on the flip of a coin.

While people understand the concept of probability (we know we have less chance of being hit by a ball if only one is thrown at us rather than twenty), when they need to assess multiple outcomes they tend to suffer from an optimism bias and put too much weight on good outcomes relative to bad ones. For example, people are more likely to leave their umbrella at home if there were a 45% chance of rain versus a 55% chance of rain, even though the probable outcomes are not that different. This means investors can overestimate the chance of yields returning to what they think of as ‘normal’, rather than what we have actually seen since the Global Financial Crisis, which is a slow grind to zero.

Bonds are not equities

Government bonds have a known maturity (i.e. you will get your capital back with certainty at a fixed date in the future). Unlike equities, price changes for bonds are not uniform and are dependent on both time and changes in rates. Bonds of longer maturities normally have a higher yield than those with shorter maturities, but they also have a greater sensitivity to changes in interest rates.

This characteristic of bonds provides opportunities for investors that may not be available in other asset classes. Government bonds are available in maturities from 1 year to 30 years in the Australian market (and as long as 100 years in offshore markets). This also means some of the potential negatives of owning bonds can be minimised while still having certainty of income and payment on maturity.

This ability to move up and down different maturities on the bond yield curve could be a major driver of returns for investors over the next few years even if yields remain steady.

With so many bonds to issue, why aren’t rates higher?

The glib answer is because governments can’t afford them to be higher. As long as government deficits remain high, rates need to remain low to keep interest payments affordable. We use US data to illustrate this point due to its longer history, but there is little to suggest Australia would behave any differently.

Government bonds issued in local currency cannot default because the government can effectively print money to repay them. This could have negative impacts on both inflation and currencies if it were to occur and increases the risks to foreign investors. However, as long as governments can finance their interest payments from taxation and other receipts, this is less of an issue.

Overall, Australian government debt remains low by global standards at 50% of GDP (after taking into account the current stimulus measures). The impact of higher interest rates on debt payments was illustrated in the US Congressional Budget Office’s Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030 (issued prior to Covid-19) (https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56073). It projected US debt to be as high as 200% of GDP by 2050. This report estimated that total net interest outlays would rise from 1.7% to 2.6% of GDP by 2030. Of this amount, two-fifths were attributable by an estimated increase in 10-year yields from 1.8% to 3.1%, representing an additional USD $284 billion.

This would suggest not all government bond markets are as attractive as Australia’s and that foreign bond exposure may bring with it other risks not considered in this wire

To own bonds or not, sometimes you don’t get a choice

Governments have many ways to coerce ownership of bonds, for example forcing regulated industries to own for liquidity or capital purposes. In the 1940s, the use of Yield Curve Controls (YCC) provided investors with a more certain outlook for a period of time and an environment where It made more sense to own bonds than not. In 1941, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) on page five of this report suggested that:

“…a definite rate be established for long-term Treasury offerings, with the understanding that it is the policy of the Government not to advance this rate during the emergency.”

This is recognisable as today’s “lower for longer comments by central banks” and is also reaffirmed by the Fed:

“…when the public is assured that the rate will not rise, prospective investors will realize that there is nothing to gain by waiting, and a flow into Government securities of funds that have been and will become available for investment may be confidently expected.”

So in effect, the central bank provides conditions where owning bonds should provide a reasonable return with some certainty. The benefits to owning bonds under these conditions are two-fold:

- Firstly, they face a positively sloped yield curve in a market where yields are at or near their ceiling levels. Investors can move out the curve (i.e. by buying longer maturity bonds) to pick up higher coupon income without taking on more risk.

- Secondly, investors can, over time, ride a position down the positively-sloped yield curve (i.e. over time the bond will gain in value from the passing of time because shorter rates are lower than longer rates). This is often described as roll-down return.

Could inflation be a problem for the economy or rates? History is mixed.

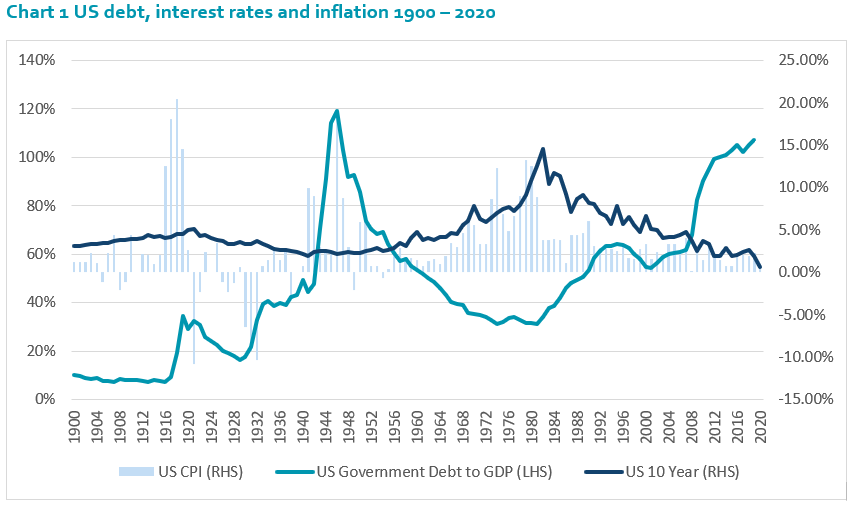

Source: TreasuryDirect, MeasuringWorth.com, multpl.com, Bloomberg

The 1970s, ’80s and ’90s are often quoted by bond bears as representing the case for not owning bonds at low rate levels. These periods were characterised by periods of rapidly rising interest rates and higher inflation.

Chart 1 shows US government debt to GDP relative to the 10-year US bond rate and US CPI. In all cases where debt levels spiked, rates remained low or started falling. Rates were only able to rise rapidly when debt was relatively low. Intuitively, this makes sense as it takes higher rates on a lower debt balance to cause enough ‘pain’ to start to slow an economy that is overheating. When debt levels are high rates need to rise less to inflict the same hand brake effect.

The relationship between bond rates and inflation has strengthened since the 1980s when inflation targeting by central banks began. Prior to that period, there is less evidence that inflation matters to bond yields. Inflation did spike higher during the 1940s, but interest rates remained low and it would appear the debt burden is more important than inflation to the level of interest rates.

Is now different?

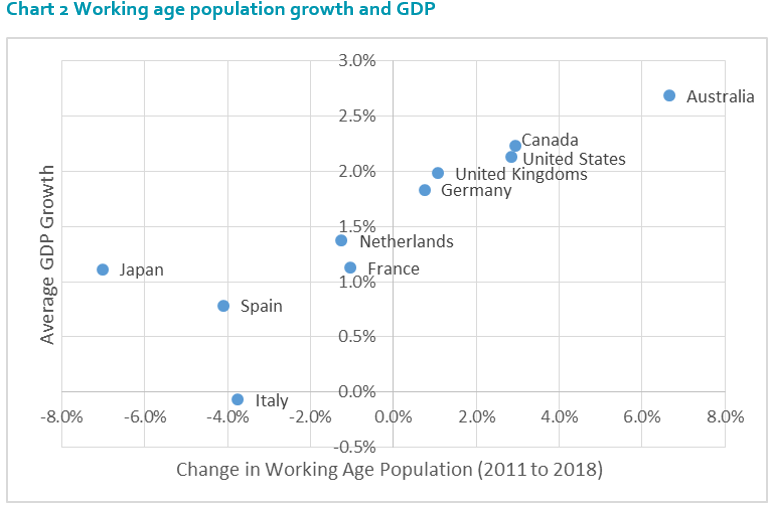

Source: Bloomberg, United Nations DESA Population Division

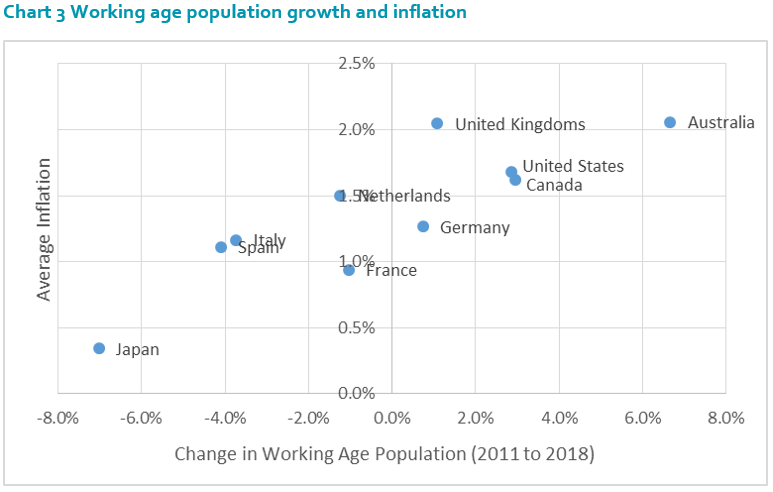

Source: Bloomberg, United Nations DESA Population Division

History is only a guide to the future, however current conditions definitely appear to be different. I believe demographics play a significant role in how economic growth is impacted by shocks in the system and, more importantly, the path out of the shock.

The 1940s were the start of the baby boom, which saw a large increase in the working age population. This, coupled with rapid technological change in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s ensured a period of relative prosperity, higher growth and incomes, and less global conflict. Now those same baby boomers are heading to a retirement phase and working age populations will decline. Charts 2 & 3 show the impact on various economy’s GDP and inflation as population growth declines and, more significantly, as working population growth declines.

We are also witnessing a potential increase in global conflict and a threat to globalisation. Technology is still evolving rapidly but the benefits may be less widely spread as in previous decades, with a more uneven distribution of wealth. This is likely to be an environment where bonds continue to remain attractive particularly given GDP growth, inflation and interest rates are likely to remain low for many years and significantly lower than the past 30 years.

Certainty out of uncertainty

Bonds may lose money during times of strong economic growth, rising interest rates and higher inflation, however, these bond losses can be offset by the gains on riskier assets in a portfolio.

Losses on bonds are usually small compared with the potential losses in riskier asset classes and bonds generally recover much quicker. No one would suggest a 100% allocation to government bonds is a balanced investment strategy; likewise, not having an allocation to bonds should also be considered unbalanced.

But a known return in an uncertain world, where returns on all asset classes are likely to be lower than the past, might just be a good thing to have in a portfolio. This is particularly true given the large cohort of baby boomers heading to retirement who may not have five or 10 years to recover from another major shock to risk assets.

The question isn’t why would you own bonds but, in the current environment, why wouldn’t you own bonds to deliver certainty in such uncertain times?

About the series

Livewire asked two of our contributors who have strong views on government bonds to produce a bear versus bull case on this critical sector for fixed income and defensive investors. View all the wires in this series:

Stay one step ahead of the crowd

Our investment philosophy is based on identifying pricing anomalies. Inherent in this philosophy is the belief that markets are often incorrect in forecasting short-and medium-term influences and conditions. Keep up to date on where we believe the market has got it wrong by hitting the 'follow' button below.

2 topics