Why you should forget buying the dip and take a slower approach

Wouldn’t you love to buy up big just as the market bottoms out? Only to sell later at the peak and make a massive profit. While investors used to fear falling markets, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a change of behaviour. Investors poured in trying to find the quick wins and undervalued treasures in volatile markets. Did they get their quick wins? I suspect not given we’ve moved to a period of high inflation and rising interest rates… and the bears are lumbering in.

Even the most experienced fund managers can have trouble picking the lowest point of a trough. They often rely on a range of signals to give them an indication that things might be about to turn. One signal might be an up day after a period of prolonged falls in an index like the ASX200 or NASDAQ100 which isn’t followed by a dramatic fall again. Another might be put/call ratios, a contrarian indicator. A higher ratio of puts suggests that the market bottom is near (that is, investors are pessimistic so things might change) while a higher ratio of calls suggests that a market top is near (investors are getting too optimistic).

The point is, it’s a fairly imprecise science and it can be challenging for an investor to pick it right. So, what’s the solution you may ask?

Dollar-cost averaging

Sounds tedious but it's really very simple. Another term for it is a ‘regular investment plan’. Think of it as being like your ‘regular savings plan’ for that emergency savings account that you *definitely* have and monitor. It’s been around since the late 40s when it was referenced in Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor.

It’s effectively what you are already doing with your superannuation contributions.

What does it look like?

You choose a set timing and set sum to regularly invest in the market. It could look as simple as $20 a month adding to a managed fund or purchasing additional shares in a particular company. It could be a larger amount spread across a range of investments too. Either way, it’s an amount you commit to regardless of what the market is doing – be it rising or falling.

The first thing to note is: yes, that does mean sometimes you’ll be buying when the market looks expensive. But it also means you will be buying when the market looks cheap. The idea is that it should all ‘average’ out in the long term.

The second thing to note is that this isn’t a strategy for short term investors. It’s all about the long term planning and it should tie nicely into the third thing to note… compounding!

Compounding is easily one of finance’s few free lunches. The longer you are invested, you earn returns on the principal you invested, plus earn returns on top of your historic returns (assuming you reinvest) and it all keeps accumulating over time. You can look at how compounding works in this calculator from MoneySmart.

Sounds nice - but does it actually work?

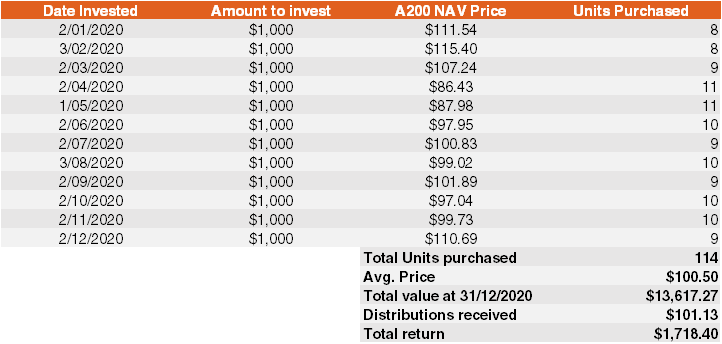

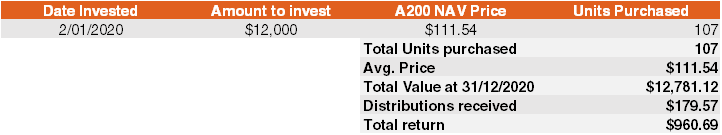

Here’s a worked example from BetaShares which compares investing $12,000 in the BetaShares Australia 200 ETF (ASX: A200) using dollar-cost averaging compared to a lump sum investment across 2020.

In this case, the investor is actually financially better off both in terms of the average price paid per unit and total value – though receive less in terms of distributions across the period of one year.

It’s worth noting in short periods, the strategy works better in a falling market than a rising one along with volatile markets such as in 2020. In a rising market, you may actually be better off investing with a lump sum at the start. The ideal approach otherwise is over many years (or even decades) where you are operating through a range of market cycles.

And on to finance’s free lunch: compounding

Compounding benefits not only from regular investment but also reinvestment. That is, you reinvest any earnings you make on your investment using methods such as dividend reinvestment plans or the like.

Just like in a savings plan, your returns get compounded. Earn returns on your returns. But as in all things, caveat emptor. Market activity might mean the value of your investment falls or makes losses so no returns to compound. It’s not like earning compound interest on a cash deposit.

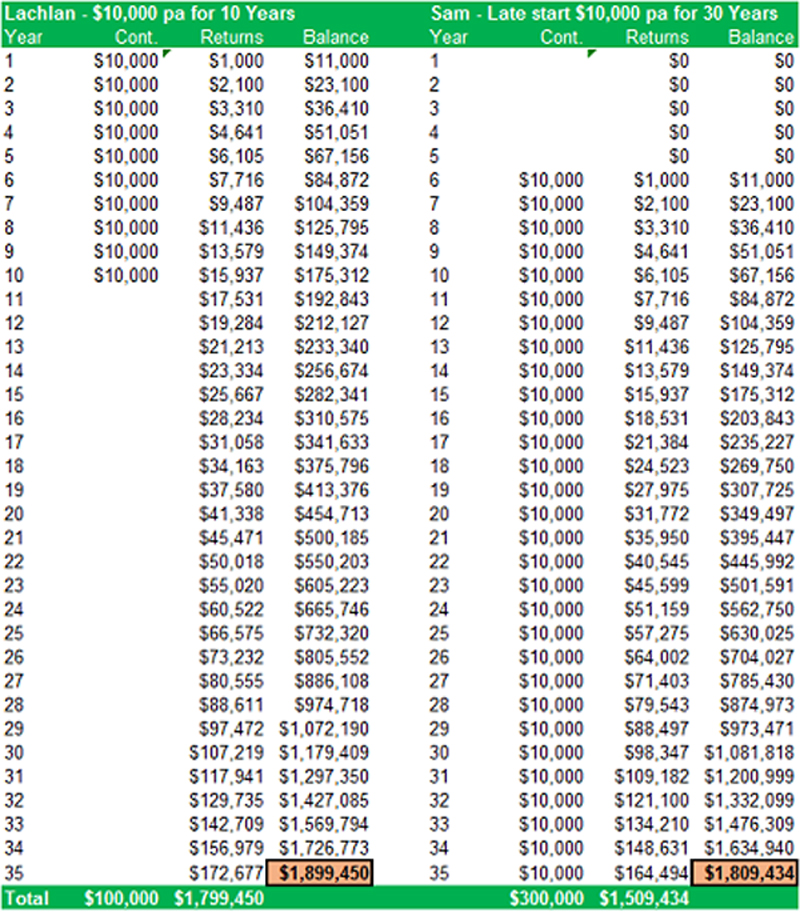

Here’s a demonstration from an article by Daryl Wilson of Affluence Funds Management on how it could work. It compares two investors - Lachlan who invests $100,000 from years 1-10 and then allows the investment to compound and Sam who starts later and invests $300,000 over years 6-35. You can read the full article here.

Putting theory into action

Depending on how you invest, you can set up a regular investment plan aka dollar-cost averaging in a range of ways. For example, if you invest into a managed fund, you could set up a regular transfer of a set amount into the fund from your bank account.

You can set up reinvestment plans through share registries and fund issuers - it can vary depending on the type of investment and structure.

As with all things financial, whether or not dollar-cost averaging and reinvestment (for compounding) is a good idea for you depends on your life circumstances, needs, goals, objective and strategy. Talking to an expert can help you decide what is right for you.

Other relevant articles you might find helpful:

2 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 contributor mentioned