Why you should take a closer look at Indian equities

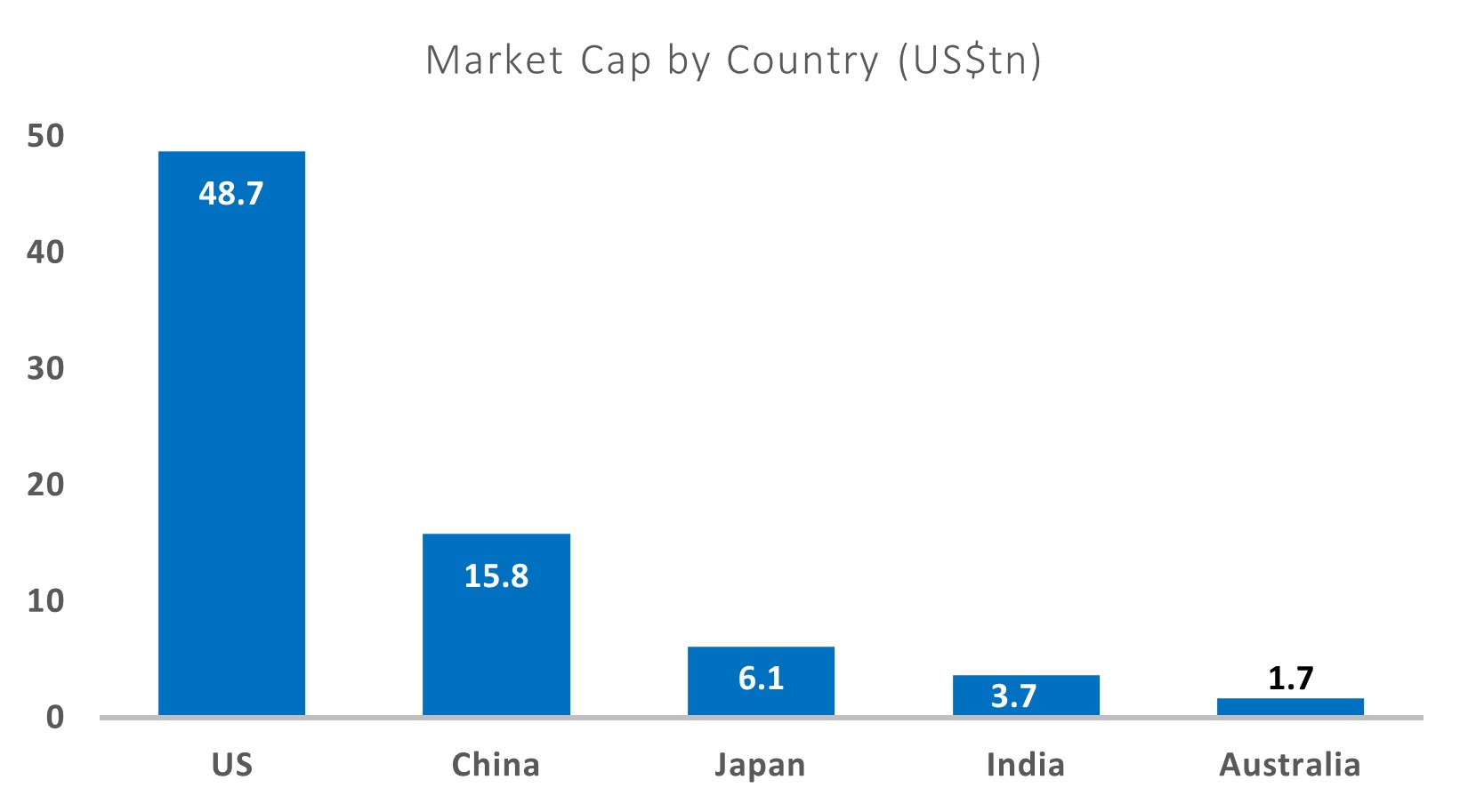

Equity market capitalisation globally stands at just over US$106tn. Over 44% of market cap is to companies listed in the US (this percentage rises to 60% in the MSCI All Country World Index), which is the world’s largest equity market. Next in line is China/Hong Kong which together comprise 14% of global market cap. Japan makes up the top 3, with a market cap contribution of 6%.

It would surprise many readers to know that India is next in line with a market cap above US$3.7tn. However, it shouldn’t be a surprise given India is the world’s 5th largest economy, with a significant privatised component.

For many, India’s GDP growth, equity markets and companies, remain a myth because their "crystal ball" doesn’t extend past developed markets. Some common reasons we hear from financial intermediaries/advisors on the logic of not having a dedicated exposure to India (via an India focused fund or ETF) are:

- We prefer to invest in broad strategies which include all Emerging Markets or Asian markets. India is too niche!

- We don’t have the bandwidth to research individual countries

- Individual country economics, currencies, politics and markets are hard to predict

- And by the way, India is too expensive

Some of the logic provided by consultants, researchers and other ‘gatekeepers’ to the Australian wealth industry, is in fact a disguise for it’s too much “career risk” to take on when it comes to "sticking their neck out" on India.

Firstly, India is a significant equity market, which is more than double Australia’s market capitalisation and more than three times the listings. Whilst investing in Indian stocks requires a Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPI) license, this can be easily set up within two months. Additionally, India’s currency has full convertibility, making it relatively easy to invest in with enough liquidity in the top 500 stocks.

India is definitely not niche. It would take a brave forecaster to suggest India is not going to end this decade (if not earlier) as the world’s 3rd largest economy and with an equity market capitalisation close to US$7tn, only behind the US and China[1]. Australian equities if anything is more niche, but investing locally has “lower risk" due to familiarity, favourable taxation for dividends, no currency risk and transparency. However, given we can see India’s economic and equity market path, would it not make sense to consider a specific “strategic” and long-term allocation that provides exposure to the aspects of the market, leveraged to Infrastructure, Manufacturing, Exports and Real Estate industries – key drivers of the growth story as India rises in prominence in the “new world order” (G3 of US, China and India - as discussed at the recent World Economic Forum, August 2023).

20 years ago it made sense to consider ‘buckets’ like Emerging Markets due to allocators globally taking this route and more homogenous thinking on non-Developed Markets, as a unified proxy for fast growing economies (as well as being an anti-USD trade). This trade aligned with globalisation and views on the US economy/currency versus the rest of the world. In an environment of de-globalisation, friend-shoring, supply chain diversification, the correlations intra emerging markets have broken down and the economic, market and currency fortunes of the pack are showing increasing dispersion.

Would it not make sense to research one country in depth when it is likely to lead to greater certainty in the outcome than favour breadth of choice, where the outcome is diversified but likely to be sub-optimal? Is it in fact a case of di-worse-ification?

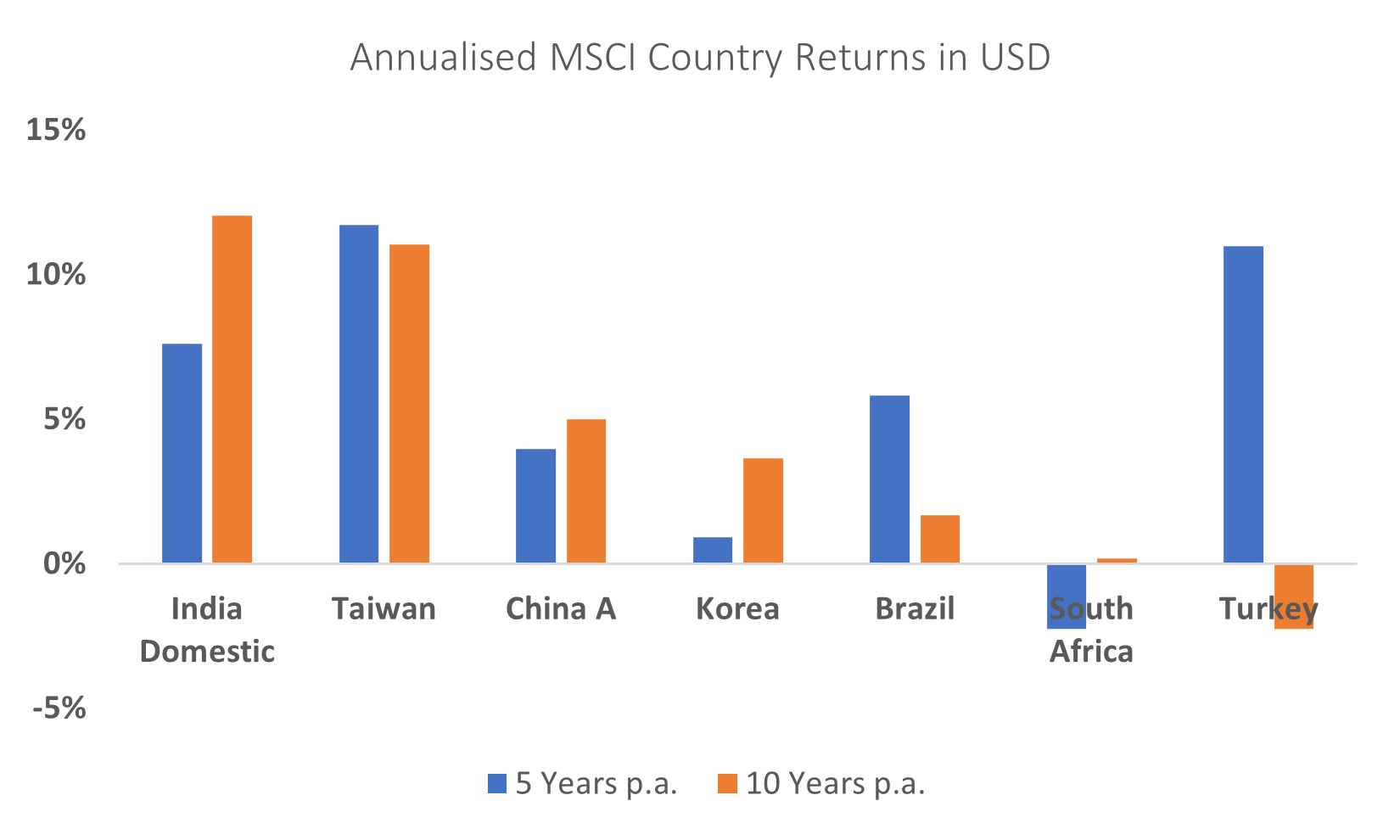

We have seen Russia, China, Turkey, Korea, South Africa and Brazil from time to time drag the MSCI EM benchmark lower over the last 10 years. Taiwan has performed well over the last 10 years, driven by one industry and particularly one stock – a stock owned by most global funds already (Taiwan Semi Conductors).

When it comes to broad strategies like Emerging Markets (EM) and Asia ex-Japan, in comparison to India - over the last 20 years, the MSCI India has outperformed MSCI EM significantly and over 75% of rolling 5-year periods.

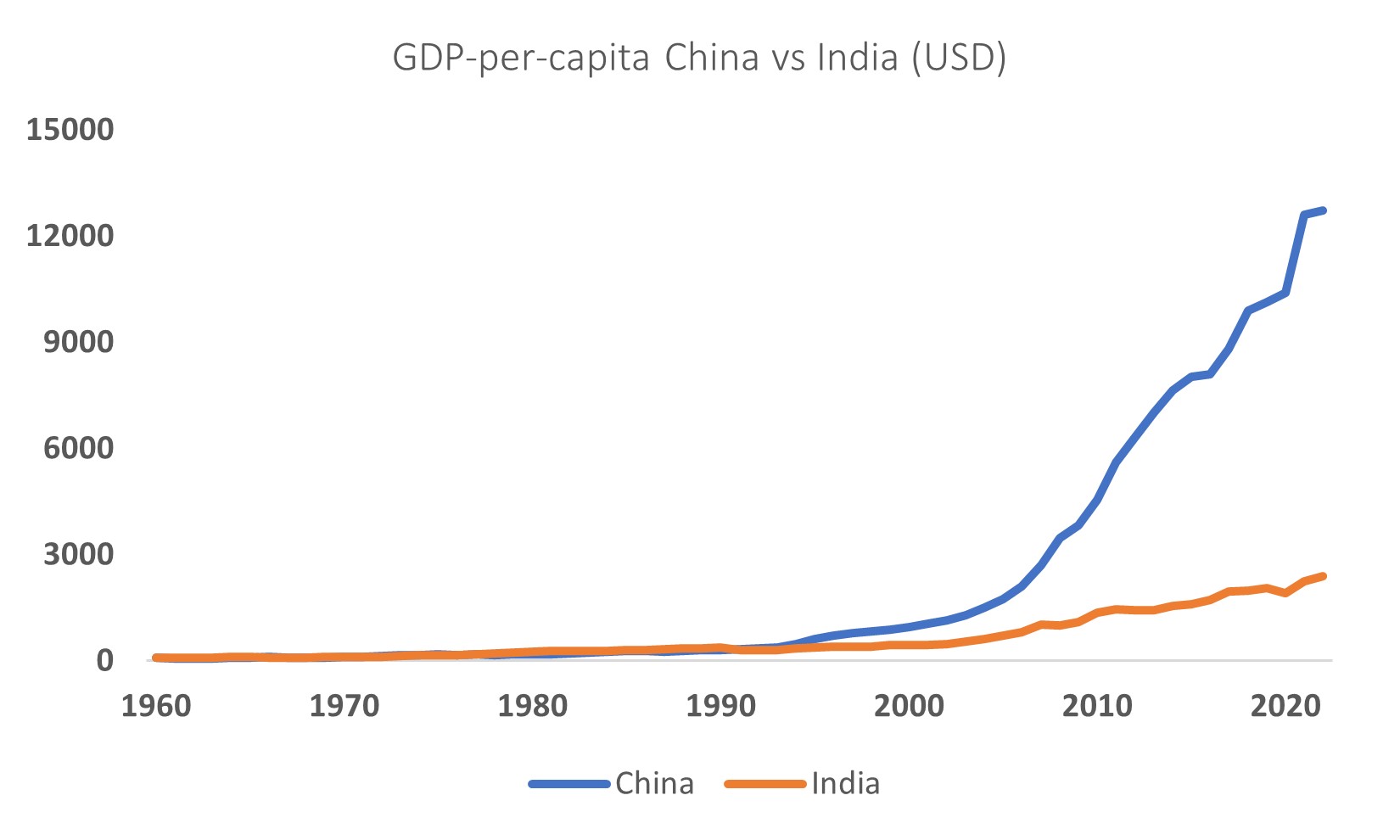

Never before has there been such a period where India’s macroeconomics (GDP growth, forex reserves, PMI’s), banking system (non-performing loans have reduced drastically since an Insolvency & Bankruptcy reform was passed in 2016) and balance sheets (corporate, government and household) have been aligned for success. Economic reform and infrastructure spending are the icing on the cake for productivity gains in the future. Finally, the financialisation (shift towards financial assets, access to bank accounts, rising wealth), formalisation (shift towards formalised, branded business and aggregation of profit and efficiency) and digitisation (national ID card, Smartphone and Internet penetration) of India are providing the impetus for rising GDP-per-capita (which is 16 years behind China) to play catch up over the next decade.

India is about to hit its productive zone in terms of number of people employed (22% of global employable population). In 1990, India and China both had the same GDP per capita!

India is a democracy, operating under English Law, a constitution and ever improving governance norms for business. This ’rising’ is likely to create a positive premium for investors to benefit from.

Is India too expensive? This is a story put forward by global fund managers who tend to operate at the highest levels of benchmark constituent weightings and liquidity. Sure, of India’s 6000 plus listed stocks, only 500 are investable (with liquidity for global investors). However, these 500 companies offer significant breadth and depth by sector. The valuation ‘problem’ is housed predominantly in the top 50 (defined as the Nifty 50) which tend to be the most liquid and most recent success stories (Financials, Consumption and Information Technology biased) of the last decade. The top 70 stocks by market capitalization, take you down to a market cap of US$10bn, whilst the top 10 are close to US$1tn of the US$3.7tn of market cap.

To access the growth story, investors need to invest further down the cap curve and not list liquidity as their first priority. Investors (particularly institutional Superfunds) gladly go down the illiquid path elsewhere – that is the irony! When going further down the cap curve there is a greater representation of manufacturing, local demand driven businesses, engineering, infrastructure, pharmaceuticals and real estate which are not as expensive and offer compounded earnings growth over the decade.

At the end of the day, “gatekeepers” want to make their jobs easier by “simplifying” the process. I am not sure that necessarily aligns with what is best for long term wealth creation as well as demand for capital growth in an environment where growth is going to be scarce.

Allocating specifically to India should be part of an overall investment strategy, especially given that Indian equities are backed by fundamentals of compounding earnings growth and exhibit low correlation to Australian equities and AUD assets generally. This illustrates a better risk-return metric for balanced and growth risk profiled portfolios when added in comparison to Emerging Market funds (due to the improved correlation benefits).

[1] These are India Avenue estimates based on IMF GDP growth forecasts and current market-cap-to-GDP ratios.

5 topics