Will Aussie banks rebound from here?

In recent weeks, the share prices of Australian banks have been heading south. The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (ASX:CBA) and Westpac (ASX:WBC) have been hit particularly hard, on the back of material falls in their net interest margins. Will margins start to expand soon as the interest rate on fixed rate loans starts to climb again?

Three of the four major banks have reported their FY21 results while CBA has released its quarterly update over the last couple of weeks. Between 27 October and 19 November, the ASX 300 Banks Accumulation Index has generated a loss of 4.87 per cent, 6.26 per cent weaker than the return generated by the broader market of +1.39 per cent.

However, the returns generated by each stock have varied significantly, reflecting the market’s relative degree of surprise resulting from the earnings reports with Westpac delivering a -12 per cent return, CBA a -7.8 per cent return, while National Australia Bank (ASX:NAB) and Australia and New Zealand Bank (ASX:ANZ) have delivered a -0.2 per cent and -1.3 per cent return over the period respectively.

The main point of difference between the results has been the change in the net interest margin (NIM). The change in net interest margin and growth in average interest-bearing assets determine the growth in net interest revenue for a bank.

Net interest margins for Westpac and CBA fell materially in the latest period, and in the case of Westpac, accelerating to the downside through the period with the net interest margin materially lower at the end of September than the 2H21 average.

This contrasted with NAB and ANZ, which reported relatively stable net interest margins in the 6 months to September 2021 relative to the 6 months to March 2021.

The materially lower than expected NIMs reported by CBA and Westpac result in lower forecast NIMs in determining earnings expectations in future periods. The reduction in earnings forecasts was the main driver of the weak share price performance for the two banks over the last 2 weeks.

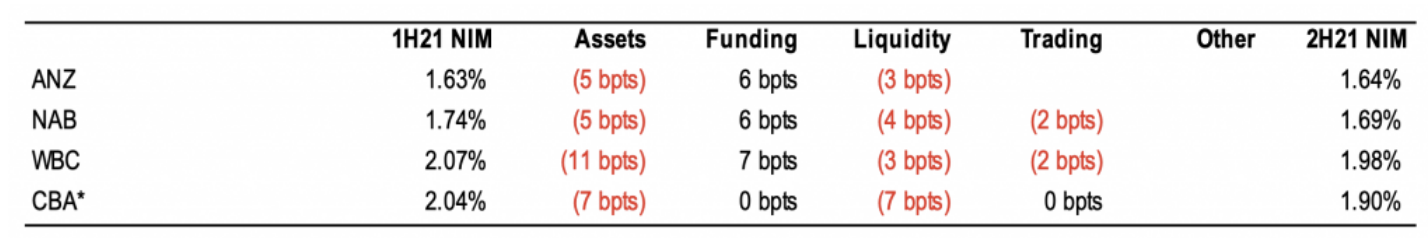

In looking at why the NIMs for CBA and Westpac fell so much relative to NAB and ANZ, we need to look at the components of margins and how each of these factors moved. The table below sets out the primary drivers of NIM between:

- Asset returns – essentially the rate of return generated from the loan book. This is impacted by competition as well as changes in the mix of loans in the book (mortgages (fixed/variable rate, principal and interest/interest only, owner occupier/investment), unsecured consumer credit, business (SME or institutional), or by country.

- Funding – changes in the cost of funding. Impacted by changes in the benchmark (BBSW/swap) for deposits and wholesale funding, mix (transaction/term deposit/savings accounts, business accounts, short term/long term wholesale), changes in borrowing spreads, and more recently the absolute floor of 0 per cent interest for deposits under the current near zero interest rate policy of the RBA.

- Liquidity – banks and other authorised deposit taking institution (ADIs) are required to hold a certain amount high quality liquid assets and other liquids assets. These are usually government or semi-government 3 and 5 year bonds, residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS) and asset backed security (ABS). At present these assets earn a rate of return well below the return generated on the loan book but pretty close to the cost of funds. As such, increasing the amount of liquid assets held as a percentage of the loan book reduces/dilutes the NIM but is fairly neutral to net interest income.

- Markets/Trading – this increases or decreases the NIM in a given period depending on the performance of the Treasury team in managing and trading risk relative to the prior period.

The table below sets out the impact of each of these factors in the 6 months to September 2021 (3 months for CBA) for each of the major banks.

Figure 1: Drivers of NIM in the most recent reporting period

Source: Companies and Montgomery estimates

*CBA is for the 3 months to September 2021 relative to the 6 months to June 2021. The company did not report a split between the impact of asset returns, funding costs and trading activity on NIM in the quarter

One of the problems in looking at this data is the difference between an average over the 6 months relative to the performance in any given month or quarter. NAB reported in its June quarter trading update that its NIM had increased excluding the impact of the Treasury and Trading. However, for the 6 months to September, NIM excluding the impact of Trading fell 3 basis points (bpts). This implies September quarter NIM excluding trading was down materially more than the 3 bpts.

For CBA, June quarter NIM was lower than the 2.04 per cent reported for the June half. Therefore, the fall in NIM relative to the exit rate in June was less than the 14bpts reported in the September quarter relative to the 6 months to June.

So, what happened to the industry in the September quarter?

Essentially the issue was a margin squeeze in fixed rate mortgages and most of the benefits on funding costs having flowed through by the end June. The term funding facility (TFF) provided by the RBA (3 year funding on new lending) provided ADIs with extremely cheap funding to provide low fixed rate mortgages on a duration matched basis. This is why 3 year fixed rates fell as low as 1.80 per cent in the last 6 months.

However, this funding source stopped at the end of June. Additionally, the banks were very active in reducing term deposit rates in the 6 months to June. By July, there was little room for further downside movement. Funding costs did benefit from depositors rotating from term deposits to transaction accounts and there has been some compression in wholesale funding spreads, but this was offset by a reversion to funding on an incremental basis at the swap curve rate plus a margin.

For 3 year fixed rate mortgages, incremental funding moved from 0.1 per cent under the TFF to the 3 year swap rate of around 0.30 per cent plus a margin. This immediately reduced the net interest margin generated on these products.

Then in August, the short to medium term end of the swap curve started to move up, with 3 year rates increasing from around 0.30 per cent in July to 0.50 per cent in September, putting further pressure on net interest margins. However, 3 year fixed rates remained low due to intense competition (led by Westpac) and the decision to support households during the lockdown.

In October, 3 year swap rates spiked even higher and are currently over 1.3 per cent. This is why fixed rate mortgage pricing has been rising significantly in recent weeks, with most of the banks announcing multiple increases.

With little incremental support coming from funding costs, increasing pressure on fixed rate mortgage margins, and rising liquids holdings, October net interest margins are likely to have been even weaker for all of the banks.

The good news is that fixed rate pricing has now moved to levels that will see both a recovery in margins on these products, and an increased flow of demand into variable rate products now that variable rates on offer are below fixed rates. If 3 year swap rates stay at current levels, expect fixed mortgage rates to move back above 3 per cent in the near term. This should see October represent the low point for bank net interest margins unless there is another break-out of intense competition.

4 topics

4 stocks mentioned