Your diversification free lunch is not “all you can eat”

Nobel prize winner Harry Markowitz gets the credit for coining the phrase that “diversification is the only free lunch in finance”. Add the insight that stock markets are at least semi-efficient, and a multi-trillion dollar exchange-traded fund (ETF) industry was born.

And indeed, many exchange-traded funds are worthwhile investments, providing low-cost diversification. But some take the argument too far. You do pick up a benefit from diversification. But, don’t pretend that diversification means you can:

- Afford to overpay for stocks or

- Ignore asset allocation

Diversification doesn’t mean you can overpay for stocks

There Is No Alternative, also called TINA by the cool kids, is a common reason to buy stocks. And it is a pure coincidence the reasoners often make money from you owning stocks…

Reasoning: Interest rates are almost zero. Central banks are crowding investors out of low-risk investments. Yes, stocks are expensive, but they are the only game in town. There Is No Alternative. Even though individual stocks are risky, you can buy an index, get diversification and then keep buying.

I guess if you believe that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau”* then these arguments stack up and maybe There Is No Alternative.

But stocks can go down. A 3% return on stocks is higher than 0.5% on cash or government bonds. But is it better? The cash or government bonds have a known payoff; stocks need a higher return to justify the dramatically higher risk, including the risk of loss.

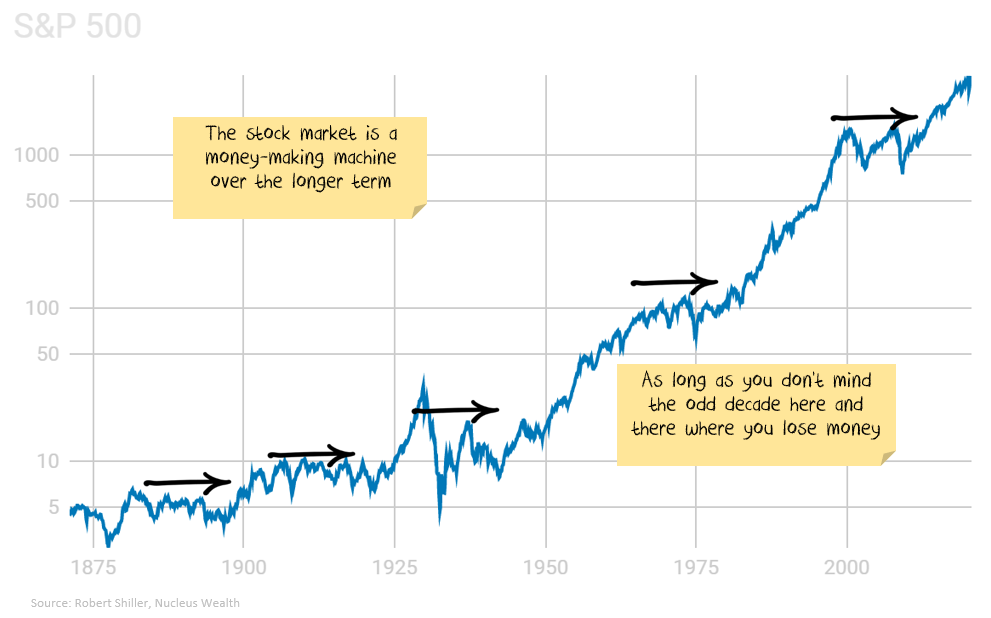

A diversified portfolio will help, but the stock market often goes through ten year periods where it goes backwards. Being diversified is no protection from long market drawdowns.

How much of the current market rise is due to passive investment?

I’m increasingly asked about the effect of passive investment on the stock market. In particular: is the current over-valuation a structural change because of the rise of passive investing?

Now, I’m an active manager. So, I like to blame passive managers as much as the next guy. But, it is difficult to pin overvaluation on passive investing. The first argument “for” (below) has some merit, but the arguments get progressively weaker:

For: Passive investors hold a lot less cash than active, and so a switch from active to passive pushes up prices. Against: Active investors are more likely to use leverage.

For: Passive investors are generally price-insensitive and therefore buy regardless of market pricing. Against: Active investors also make mistakes. Once someone has decided to invest, whether they invest in active or passive is a moot point – the money is entering the market regardless.

For: There is a generational element where older investors (who tend to have active portfolios) are withdrawing money from the market, and younger investors (who tend to be more likely to be passive investors) are adding money. Against: Older investors have a lot more money than younger. There are also more baby boomers retiring now and drawing down than we have seen in the past.

For: The trend towards passive is accelerating. Against: Passive or active doesn’t matter. What matters is whether the total amount being invested is increasing.

For: Passive investors are decreasing the “free float” available to other investors, increasing volatility. Against: The amount of free float reduction matches the reduction in active investors, so the dollars per active investor doesn’t change. Active managers can get caught in group think which also increases volatility.

Asset Allocation is really (really) important

Regardless of whether you choose active or passive, the more significant decision is asset allocation.

There is no “passive” option here. There isn’t an “index” that takes the decision away from choosing whether to invest in cash, bonds, domestic shares or international shares.

Diversification in shares is easy. Diversification across asset classes is more beneficial, but there is no default option for investors.

The closest you can get is a “strategic” asset allocation, which looks at long-term averages. But you may have to wait a long time to get average returns – strategic asset allocation doesn’t consider currency or bond rates and the risk of investing at the wrong point in the cycle. It could be 10 or 20 years before the averages revert.

The argument for passive investment

The basic argument:

- Active investors underperform the market.

- Passive funds perform in line with the market (less fees, which tend to be very low)

- therefore invest in passive

Really? You are telling me there are no winners?

The big problem with this argument is the broad brush statement that active investors underperform.

Especially once we add that that amateur investors underperform substantially.

Which leaves me confused. If amateur investors underperform, passive investors perform slightly worse than the market and active investors underperform, who is winning?

In the end, the market has to add up – i.e. if someone is outperforming, then someone else must be underperforming.

My take is:

- Professional managers as a group (there are significant differences in individual funds) tend to outperform. Then, many of those funds extract most of the outperformance back in fees.

- Index funds slightly underperform (due to fees)

- Individual investors underperform (although there are big differences in individual investors).

- The guys taking the fees win every time…

Which means that if you can find active managers who aren’t over-charging then you should end up in-front. Low cost passive is the next best thing.

* this was an assessment made by a famous economist, Irving Fisher, shortly before the crash that started the Great Depression

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

3 topics