Your portfolio may not be as well diversified as you think – Part 2/2

In an earlier wire, I walked through the three critical elements that good portfolios very often have in common – they all have a long-term core piece, most of them have a short-and-medium-term tactical piece, and some of them have a long-term opportunistic piece. That wire is here:

But how does that core-tactical-opportunistic idea get executed?

The critical first decision is to decide what you, the investor, want your portfolio to achieve.

Are you after strong growth? Do you need income? Is a balanced approach going to be right? Without the answer to this question, it is hard to build out a good portfolio.

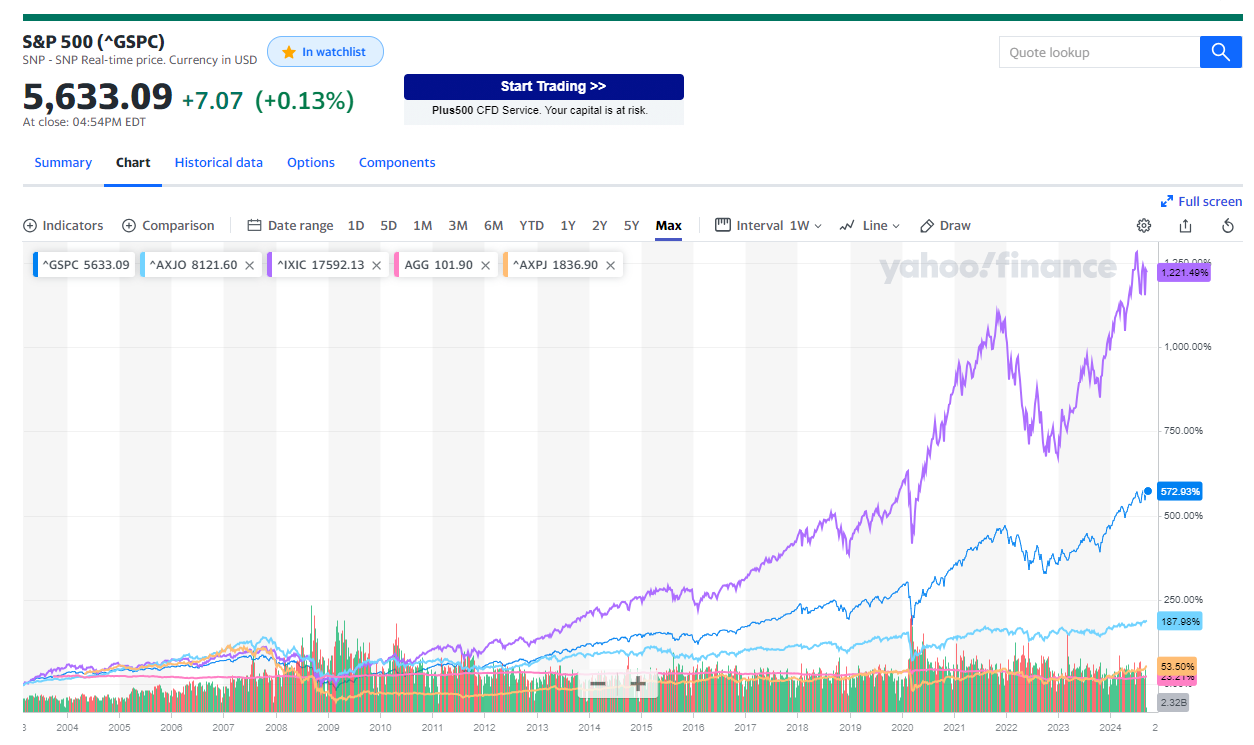

Let’s assume growth. The core piece is going to need to be constructed with both passive and active versions of strategies that have delivered double-digit growth over at least the last 5 years and more likely the last 10 and maybe 20 years. Those strategies are probably aligned with markets like the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100, markets that have driven global growth because of their exposure to the industries that have grown over the last 10, 15, 20 years. That’s technology, and AI currently, healthcare, biotech, and the like.

If instead the investor is looking to generate high levels of income, I have very good news – it is possible that there is no better tax regime on the planet for dividend investing than Australia. The franking credit system not only lowers the tax burden on dividend investors, but it also generates incentive for companies to pay high levels of dividends. If an Australian tax resident wants income, and they can live with the elevated risk that comes from stocks as opposed to other income vehicles like bonds, skewing to Australian stocks delivers high levels of after-tax income.

If an investor decides that they would like to balance their portfolio outcomes, not only is this the lowest risk option, but it is also the easiest option to execute on. The reason it’s easy is because there are no choices to make – you just include everything!! You include US stocks for growth, European stocks for value, Aussie stocks for income, and emerging market stocks for outsized alpha (although you might get outsized negative alpha…..be warned). On the more defensive side, you include some Government bonds, some investment grade bonds, some high yield bonds, a little private credit, and at these interest rates, even some cash. And for the final diversification nugget, you add some more private markets, income diversifiers, and other alternative structures (maybe merger arbitrage, litigation financing, and the like).

The purple (Nasdaq 100) and dark blue (S&P 500) lines are good proxies for growth, as are the light blue line (ASX 200) and the orange line (AREITs) for income. The pink line is the aggregate bond ETF. Your income experience is the bottom three lines, your growth experience is the top two lines, and balanced is somewhere in the middle. - - Source: Yahoo Finance.

If you decide that growth is your aim, you should expect a lot of volatility and some nervous days and nights, but if you’re willing to live through that, history suggests something around a 10% to 15% annual return over time, which will double your money in around 6 years, give-or-take a year.

If you decide that income is your aim, you should expect some volatility and the odd nervous day and night, but history suggests a 6% to 10% annual return, which will double your money in around 9 years, give-or-take a year. That said, if you take the income as your lifestyle spending, and you don’t reinvest it, that lowers your ability to compound returns into the future and it takes more like 10 years to double your money.

Lastly, if you decide that a balanced approach is ideal, you should expect the odd bout of volatility, but you will most likely have mitigated the sharp highs-and-lows. For that smoother ride, history suggests an 8% to 12% annual return, which will double your money in around 7 years, give-or-take a year.

Remember though, past performance is no guarantee of future results, and this is NOT financial advice – they are general comments and observations only.

The point is, there are several ways to skin the portfolio cat and it’s all about your overriding investment goals. Once you decide on those goals, you can diversify properly. But the idea that you can build a portfolio with a collection of (probably very poorly) picked stocks that have no relationship to each other, that have no coordination between them, and that are individual ideas that may or may not make sense or work, that’s not how you maximise your chances of success.

Roger Feder recently noted that he won almost 80% of his total tennis matches but only 54% of his total points played. That’s akin to top-tier investment management - we don’t know the answers, we only have insights into what gives us the best shot.

Good luck out there.

5 topics