Post-controversial budget, NSW attracts record $8.9bn of demand for new bond issue

After a disappointing budget blighted by heinous conflicts of interest that are costing NSW taxpayers at least $630 million a year, NSW attracted a record $8.9 billion of demand for a new, dual-tranche floating-rate note (FRN) issue from an almost exclusive bank (as opposed to fund manager) buyer base. This transaction bested the previous record set by Victoria only a few weeks ago in a similar FRN trade by a chunky $800 million. A key question is why more investors were attracted to this specific transaction than any other in the history of the State government bond market.

First some details. NSW issued twin, circa 7-year and 9-year FRNs, which many sell-side banks claimed would be too long in tenor (maturity) for some investors. The 7-year and 9-year FRNs eventually priced at 8 basis points (bps) and 16bps over the 3 month bank bill swap rate (BBSW), where BBSW is currently sitting at about 1.77%. This gives a total running yield for each FRN of approximately 1.85% and 1.93% pa (we bought both).

Why the record $8.9 billion of demand was a surprise

As with the recent Victorian FRN issue, which peaked at an astonishing $8.1 billion of demand, the NSW deal quickly grew to an even more impressive $8.9 billion of interest, allowing NSW's debt issuance agency, TCorp, to print the FRNs at or close to the tight end of the indicative pricing range. This was somewhat surprising because:

- There was a case that Victoria's record $4.4 billion FRN issues a few weeks ago, which were more than 90% bought by banks (rather than fund managers), should have exhausted some of latent demand for State government bonds from the bank balance-sheet buyers that prefer these FRNs and use them as part of their high quality liquid asset (HQLA) books;

- The 7-year FRN priced at fair value, and did not offer a new issue concession while the 9-year FRN was only about 2bps cheap (although the entire State government bond sector has become exceptionally cheap of late, which we will cover shortly); and

- Investors were roundly disappointed with the NSW budget and might have signalled their displeasure via this FRN.

To make matters even more interesting, NSW only printed $4 billion off the gigantic $8.9 billion book (ie, they printed even less than Victoria despite a bigger book), and boldly tightened the pricing, or interest rate spread above BBSW. More precisely, the 7-year FRN printed right at the tight end of the proposed range (ie, 8bps above BBSW) while the 9-year FRN was issued at 16bps relative to an initial range of 15-18bps.

It must be said that TCorp's debt capital markets team have done an exceptionally good job managing the State's financing requirements over the last 12 months, and should be distinguished from TCorp's asset management arm, which has been on a crusade to grow its funds under management in a manner that does not align with the interests of the State's taxpayers, as we have explained here.

Only $64 billion of issuance left for FY23

Given NSW had announced a theoretical funding task for FY23 of $28.2 billion (our economists believe they will struggle to spend more than 50% of the pork announced by Treasurer Matt Kean), many investors and sell-side banks thought the State might consider issuing a large $5-$6 billion deal.

While we believe NSW will eventually reduce this funding task materially, as they have done consistently in recent years, the $4 billion deal size was probably disappointing for some. It does, however, mean that NSW heads into FY23 with a still very large chunk of pre-funding secured.

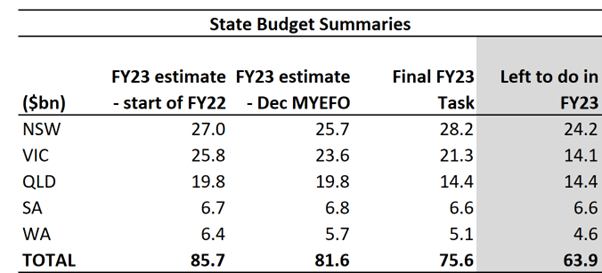

Based on the official mid-year updates in December, the five largest States in Australia (NSW/VIC/QLD/WA/SA), were expected to issue $86 billion of debt in FY23. The final FY23 budgets released in the last couple of months have slashed this task down to $76 billion. But as a result of pre-funding, the States now only have about $64 billion of issuance left to do in FY23, which is a very substantial reduction over the issuance levels in FY20, FY21 and FY22. (There will be a few billion extra from ACT, NT and Tasmania.)

A $315-$570 billion HQLA hole drove demand

All of this begs the question as to what drove the record demand for the NSW FRNs. There were two key factors at play:

- A huge HQLA hole; and

- Cheap State bond spreads.

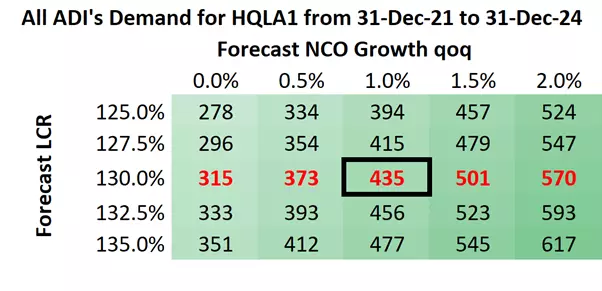

The first is the huge HQLA, or liquid asset, hole that the banking system faces. We have pioneered analysis on this subject since late 2021, highlighting that Aussie banks will have to buy somewhere between $315 billion and $570 billion of government bonds over the next 2.5 years (ie, through to December 2024) due to changes in the liquidity rules set by APRA.

Approximately $221 billion to $440 billion will be in the form of State government bonds, which represents buying that is between 4 and 7 times larger than the RBA's own bond-buying, or quantitative easing (QE), program under which it acquired $56 billion of State bonds.

To put this in perspective, the States will likely issue $70 billion or less debt each year. That means the banks will want to buy between 126% and 228% of annual State debt supply over the next 2.5 years, which is a quantum of excess demand that we have never seen before.

About six months after we first published these insights, sell-side banks have belatedly corroborated the direction of the findings with the likes of UBS concluding banks will have to buy between $275 billion and $375 billion of government bonds, albeit based on the incorrect assumption that they can lower their average Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCRs) from north of 130% to 125%. The presumption that banks can lower their LCRs well below their board-mandated targets is why UBS's numbers are a little lower than ours.

Unusually cheap spreads

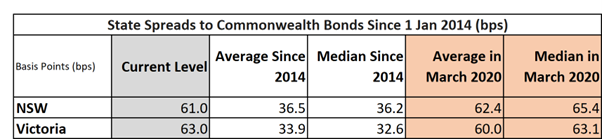

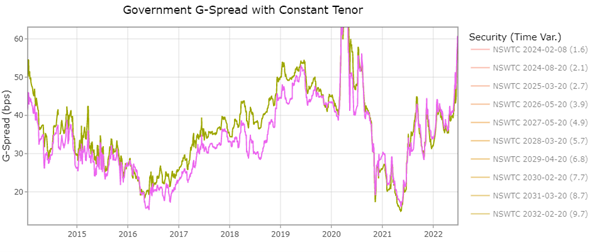

A second factor at play is that despite the unprecedented excess demand for State bonds outlined above, the fact is that State bond spreads to the Commonwealth bond yield curve have been driven-up to near-record levels. The table and chart below shows current 10-year spreads to Commonwealth bonds for NSW and Victoria compared to both their historical averages/medians since APRA first started canvassing the LCR regime in 2014 through to the current day.

NSW and Victorian spreads are both about 25bps to 30bps wider than their averages/medians since 1 January 2014. Even more remarkably, current State bond spreads are in line with the average levels observed in the 1-in-100 year pandemic shock of March 2020, which was notably months before the RBA had started its official QE program of buying State bonds in November 2020.

What makes this even more anomalous is that while State bond spreads are at March 2020 levels (as CBA also noted yesterday), other benchmark credit spreads are nowhere near those marks. For example, 5-year major bank senior bonds are trading at around 100bps over BBSW compared to circa 170bs in March 2020. Likewise, 5-year major bank Tier 2 bonds are trading at about 245bps relative to the 350-400bps levels observed in March 2020.

To make that disconnect even more bizarre, APRA's shuttering of the banks' $140 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) has actively shifted bank balance-sheet demand away from the senior bank bond market to the State and Commonwealth bond sector. Recall that banks used the CLF to, among other things, buy their own senior bonds and residential-mortgage-backed securities, which they must now replace with government bonds. As an aside, this was another event we forecast well ahead of the market, and which many banks and investors dismissed as a possibility at the time.

(Note that we focus on the period since 1 January 2014 because APRA's introduction of the LCR regime required banks to formally buy Commonwealth and State bonds as part of their liquid asset holdings that protect against a run on bank deposits and other wholesale liabilities.)

So why are spreads so cheap?

If there is huge bank demand for State bonds and reduced supply, why are spreads so cheap? There are a couple of candidate explanations. The most obvious has been a blow-out in hedging costs as proxied by so-called "swap spreads", or the difference between the market's long-term expectation of the bank bill swap rate (BBSW) and the RBA cash rate (as represented by Commonwealth bond yields). Since the introduction of centralised clearing in around 2015, the 10-year swap spread (or gap between the 10-year expectation of BBSW and the Commonwealth bond yield) has been about 15bps on average.

As a result of the RBA blowing-up interest rate markets, and the swaps market in particular, when it suddenly dumped its 2024 yield curve target in November 2021, 10-year swap spreads soared to a record level of around 36bps. Since that time illiquidity in the swaps market has driven record volatility, and on occasion pushed swap spreads to new record highs around 45-50bps (see chart below).

While this sounds complex, the simple way to understand it is that swap spreads proxy for hedging costs when a bank wants to buy a State bond and hedge out (or swap) the interest rate risk associated with the fixed-rate coupons for a floating-rate cash-flow.

As hedging costs have surged, market participants have pushed up the required yields, or spreads, on State bonds to compensate for the increase in costs.

Yet it is not that simple. As we have seen with NSW and Victoria, the States are happy to issue large volumes of debt in floating-rate note format, which requires no hedging at all by banks. Swap spreads become irrelevant if banks buy FRNs.

Second, banks don't have to use swaps to hedge fixed-rate risks: they can also use, and often do use, government bond futures instead, which completely circumvent the swap cost problem. While there are pros and cons of doing so, there is strong evidence that banks have been using futures hedges instead of swaps more regularly than they have in the past, especially when swap spreads become artificially elevated and the swaps market is illiquid.

There is a final explanation that has attracted some chatter amongst traders. The biggest buyers of State bonds are the major banks' balance-sheets (known as the "sheets"). The biggest traders of State bonds are the major banks' sell-side trading desks. While there is meant to be a Chinese-wall that separates these two areas, the sheets have been integrating more and more closely with their own trading desks to maximise the amount of trading volume the desks can claim credit for, which helps them win coveted roles as advisers on new State bond issues. In the case of the $4 billion NSW issue yesterday, the four advisers on the deal were, unsurprisingly, all the major banks.

Some traders allege that some of the major banks' sell-side trading desks have been aggressively short-selling State bonds to deliberately push their spreads wider to benefit their own internal bank balance-sheets. They point to the fact that some major bank balance-sheets and, coincidentally, their sell-side trading desks, have been vocal in talking spreads wider, and aggressive in offering-up State bonds.

If you can profitably push State bond spreads by short-selling, say, $25 million, which then allows your internal balance-sheet to much more cheaply tap the issuer for, say, $200 million, then everyone wins. Except of course the State and taxpayers. There is also the small matter of the legality of this behaviour.

This would, however, be tantamount to extreme collusion and market-manipulation, which would have nontrivial consequences for the traders and banks in question. Given these claims are based on anecdotes, and there is no definitive evidence, it will ultimately be a matter for the regulator to determine.

It would though go some way to explaining the bizarre price action, which several non-major bank traders have been surprised by.

3 topics