Questions on NSW's debt-funded, $27bn punt on stocks and global financial markets

In the AFR today economics editor John Kehoe, arguably one of Australia's best financial journalists, has an important page-one news story on how NSW's Treasurer Dominic Perrottet is proposing to load-up the State with vast amounts of extra taxpayer debt---literally more than $10 billion worth---to pursue a very risky strategy: punting this money on stocks and other equity-like investments in the hope that the gamble beats the interest repayments on the debt he would burden NSW with. If it does not, and the value of this "carry trade" falls below the debt raised to fund it, as occurred in 2020, NSW taxpayers suffer.

Never mind that sharemarket valuations are at 100 year highs, interest rates are near all-time lows, and the fact that we are moving into an inflationary cycle where interest rates are likely to climb, putting downward pressure on the valuations of the risky asset-classes that Perrottet would be punting on.

As Kehoe outlines, Perrottet's plan has not been well received by fiscal policy experts, credit rating agencies, leading banks, the bond market, and of course rival politicians like NSW's Shadow Treasurer, the impressive Daniel Mookhey. My particular interest is we lend money---alongside many other fixed-income investors---to all the major State governments, and we expect them to use that capital in a fiscally responsible fashion.

If this reckless plan goes ahead, NSW would not be meeting our very reasonable expectations. Having said that, lenders are all willing to price the extra risk and make NSW taxpayers pay via higher interest rates on their debt. This is exactly what the market has done ever since it was made aware of this proposal in June 2021.

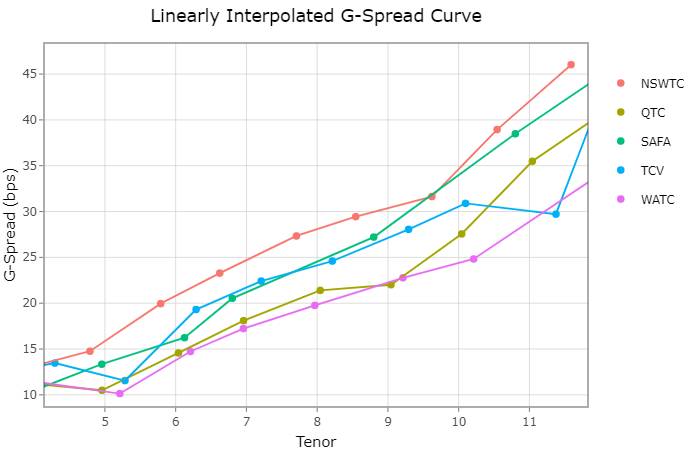

Since Perrottet's June budget surprised the market with a very material increase in debt funding needs ($35.5 billion of extra debt in 2022 compared to expectations of around $20 billion), interest repayments on NSW government debt have jumped. In fact, they've increased so much that NSW now pays more money to service additional debt than any other major state in Australia - which has never happened before.

In Perrrottet's defence, this is currently just a plan. It is entirely possible that Perrottet has received poor advice from NSW Treasury and/or the "for-profit", NSW-owned private company that is paid to run these bets: namely, NSW Treasury Corporation, or "TCorp".

Indeed, the only people that would seem to immediately benefit from the NSW State raising large amounts of extra debt to enable it to punt on stocks and global markets are the folks at TCorp (and their appointed fund managers) who would be managing this money.

Importantly, I note that neither Perrottet nor the NSW Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, have provided any comments to the AFR on this plan. So I assume they do not fully understand the risks. With this in mind, I have outlined below some key questions for Perrottet to address, which should help him think through the problems more carefully.

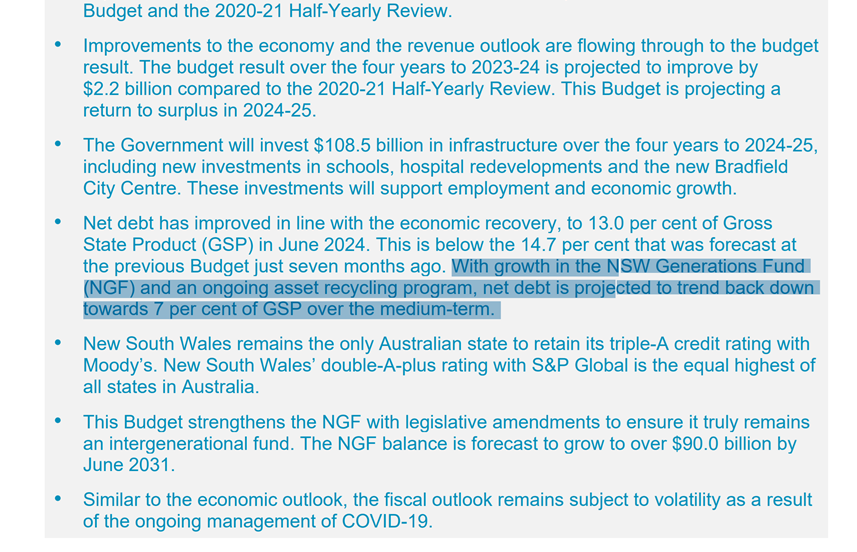

For contextual purposes, some additional detail on the plan is required. In 2018 Perrottet had a great idea: NSW was running enormous budget surpluses worth almost $4 billion a year and had negative net debt. The State was in terrific shape.

So Perrottet sensibly decided to create a rainy-day fund, called the NSW Generations Fund (NGF), which is managed by TCorp. Inside the NGF is another fund, called the Debt Retirement Fund (DRF), which holds all the money.

And Perrottet proposed to set aside NSW's budget surpluses, and any windfall money from privatisations, in the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund so that when adversity hit, and the budget lurched into large deficits, NSW had a savings buffer to reduce those deficits, payback its burgeoning debt pile, and put taxpayers in a much better financial position. Really smart stuff.

The problem is that the hurricane (or "National Emergency" as NSW has classified it) has now hit: NSW has been running record budget deficits, and gross taxpayer debt has exploded from $35 billion in 2018 when the NGF was created to what is forecast to be more than $120 billion this financial year, because of the shock induced by the COVID-19 recession.

And instead of using the $15 billion (shortly going to $27 billion when the second-half of WestConnex is sold next month) set-aside for precisely these situations in the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund to pay for all the fiscal stimulus, support new infrastructure investments, and mitigate taxpayer debt, Perrottet is currently proposing to raise large amounts---somewhere between $10 billion and $20 billion---of additional NSW government debt to further expand the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund in the hope that it earns more from punting stocks than the cost of this debt.

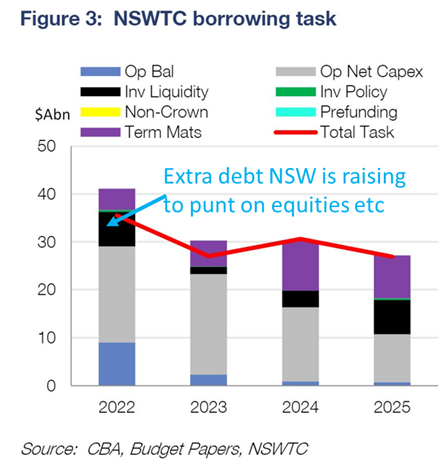

In fact, the amount of extra debt is arguably more than $10 billion to $20 billion. According to CBA, Perrottet is directing just under $20 billion into his investment funds this year and over the coming three years. Because NSW is running big fiscal deficits, that has to be funded with gross debt issuance (unless he starts delivering surpluses). In addition, the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund will shortly have about $27 billion in cash that can be used for repaying debt and/or funding the fiscal stimulus/infrastructure needs of the State. But because this $27 billion will be punted on stocks and global financial markets, NSW is not able to use that money for normal fiscal purposes. It therefore has to be replaced by extra gross debt. So the total amount of gross debt raised because of the NGF could be well north of $20 billion.

All of this is, however, very easy for NSW to fix: they just need to clarify that they will use the WestConnex money to pay for new infrastructure, and, more generally, the NGF's $27 billion to repay debt and/or help fund NSW's budget deficits.

Questions for NSW Treasurer Dominic Perrottet

1. In the media release launching the NGF in 2018, you told taxpayers that the NGF would not be used to "saddle" them with additional debt. Rather it would be used to put the budget in a much better position, repay debt, reduce fiscal risk and help maintain NSW's AAA credit rating. And yet you are doing the exact opposite: CBA, Standard & Poor's and others (see former NSW Parliamentary Budget Officer Dr Stephen Bartos' independent expert's report on this subject here) have demonstrated how NSW is substantially increasing taxpayer debt to put billions of dollars into the NGF. S&P has further explained that this can increase fiscal risk and reduce the creditworthiness of the State. NSW lost its AAA credit rating in December 2020 because of its soaring gross debt, and interest repayment costs on this debt above what the Commonwealth pays have leapt such that NSW now pays more than any other major State to raise new debt. How can you reconcile the enormous conflicts between the original intent of the NGF and how you propose to use it going forward?

This is what Perrottet said when he launched the NGF in 2018:

Treasurer Dominic Perrottet said governments have an obligation to leave finances in a better position for future generations, and the NSW Generations Fund would add to the work the Liberals & Nationals Government has already done to secure the State’s finances. “We owe it to our children to prepare for the challenges they will face in the decades to come, not saddle them with debt – with a Liberals & Nationals Government you can rest assured that commitment will be honoured,” Mr Perrottet said. The NSW Government today launched the NSW Generations Fund, a world-first sovereign wealth fund to guard against intergenerational budgetary pressures and keep debt sustainable in the long term, while also delivering for communities today...Growth in the NGF will help the Government to maintain a sustainable debt level consistent with a triple-A credit rating...“The NSW Generations Fund adds a whole new level of resilience to the sturdy financial foundations our Government has already built, to help withstand the budget pressures of an aging population in the coming decades.”

Here are some of the comments from S&P on how NSW is proposing to use the NGF:

Does S&P Global Ratings believe NSW is borrowing money to invest in high-risk financial assets? If a government were to borrow to invest in financial assets, in our view, this would weaken its credit risk profile. This is distinct from borrowing to fund real infrastructure or to prefund upcoming debt maturities.The NGF's enabling legislation does not allow the state to directly borrow money to place into the DRF. However, cash is fungible. NSW is running cash deficits and concurrently rerouting cash into the DRF that might otherwise be used to meet immediate spending needs. In turn, this means it must borrow more than would otherwise be required to plug the deficit. We therefore think the corollary to recent decisions to tip more money into the DRF is that NSW's gross debt and its financial assets are expanding at a faster pace. ...not neutral for balance sheet risk or consequently the credit rating.

Market participants have construed the DRF as a carry trade. According to NSW budget documents, the DRF has a high allocation to growth assets because of its long-term investment horizon…The NSW government[’s]… February 2021 half-year review explains that "the state's growing pool of financial assets increases the impacts of financial market volatility on the state's balance sheet ... While market risk can be mitigated through portfolio diversification and ensuring only appropriate levels of risk are taken, significant unexpected shifts in market performance, such as during the months of February and March 2020, can impact the state's financial assets and net debt." We agree with this assessment, noting that any market volatility would also tend to affect our measure of NSW's tax-supported debt in a procyclical way.

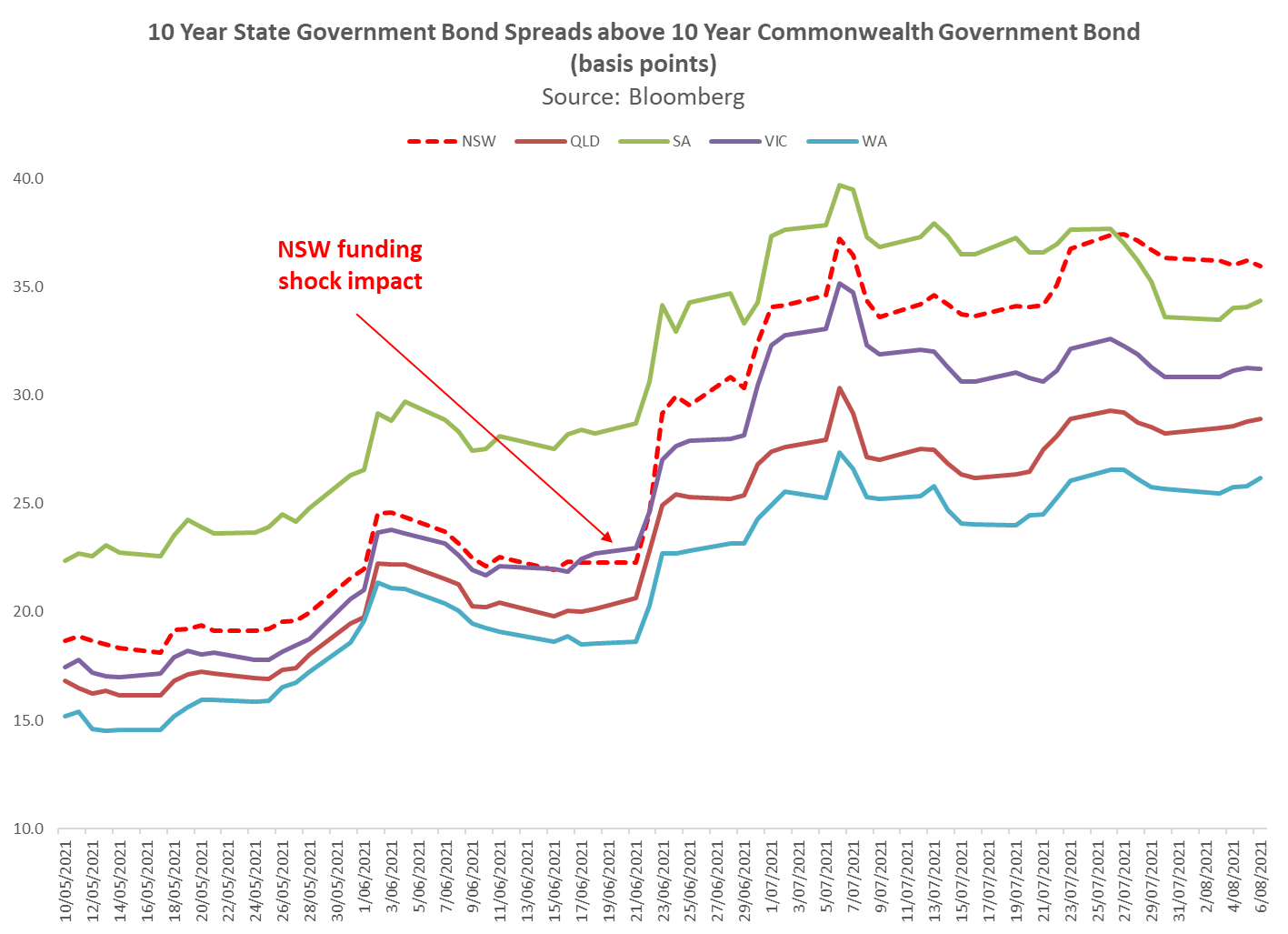

This is what has happened to the interest costs on NSW government debt relative to what the Commonwealth government pays since the Budget was released in June 2020. This chart shows the spread on State government bonds relative to the interest rates on Commonwealth government debt.

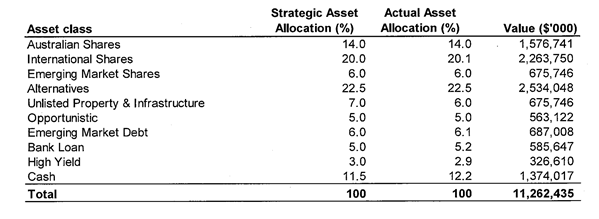

2. You have repeatedly told taxpayers that the enormous amounts of money liberated by the sale of WestConnex would be used to fund the construction of new infrastructure in a typical "asset-recycling" process. And yet TCorp has advised the market that the WestConnex money will not be used to fund infrastructure, but rather will be invested in stocks and global financial markets to fund the DRF's carry trade. Can you explain this inconsistency? (NB: The first half of WestConnex was previously sold for $7 billion and put into the NGF's DRF. The second half of WestConnex is expected to be sold in September for $12 billion to $13 billion and invested in global markets via the NGF's DRF. The DRF was 73.5% invested in stocks and "alternatives" as at its last Annual Report where "alternatives" are other equity-like strategies, normally dominated by hedge funds and private equity.)

In November 2020, the SMH reported that:

“Mr Perrottet said money generated from the sale of the remaining WestConnex stake would be used to fund government infrastructure projects and other capital works. 'Proceeds from any potential transaction will be invested into the NSW Generations Fund and allow us to continue to build world-class infrastructure such as the Metro West train line from Sydney to Parramatta,' he said.”

In March 2020, the NSW government issued a media release stating that:

“Mr Perrottet said proceeds from any future transaction would be used to extend the Government’s unprecedented $97.3 billion infrastructure program. 'Our priority is providing the schools, hospitals, roads and rail NSW needs. The Government’s asset recycling strategy has enabled us to do that and create tens of thousands of jobs in the process,' Perrottet said."

TCorp have repeatedly advised that there are no plans to use the WestConnex money to invest in infrastructure at all, and that it will be invested in global financial markets via the NGF's DRF. The latest public asset-allocation of the DRF is shown in the table below from its 2020 Annual Report.

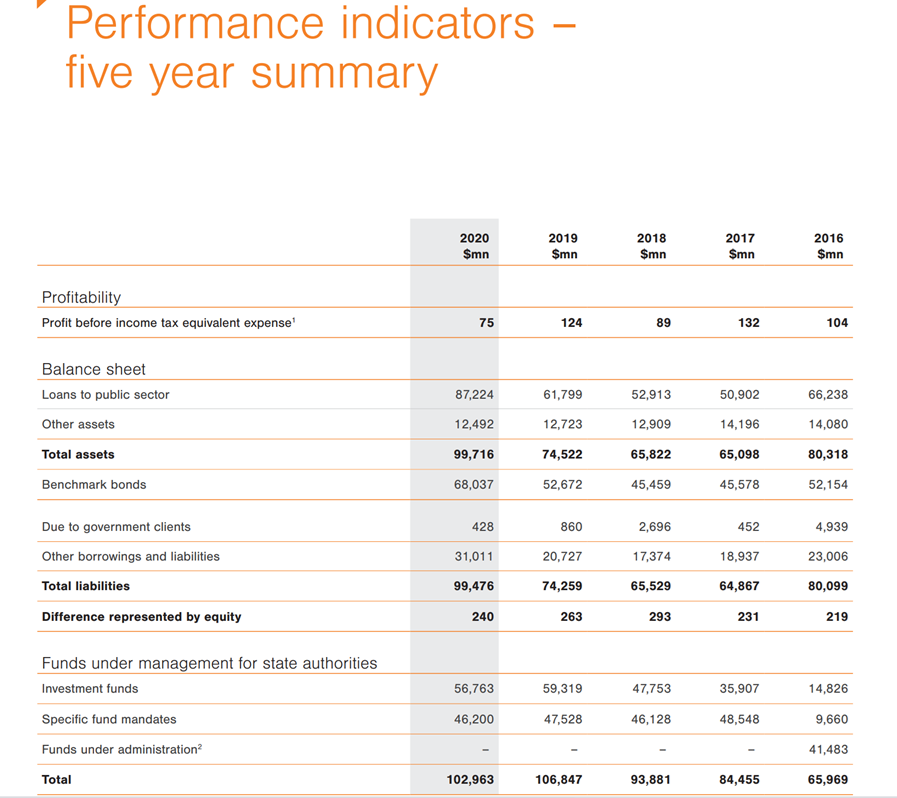

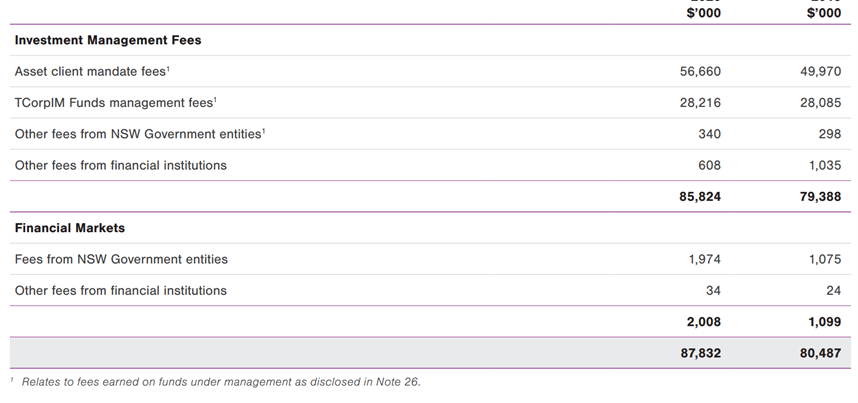

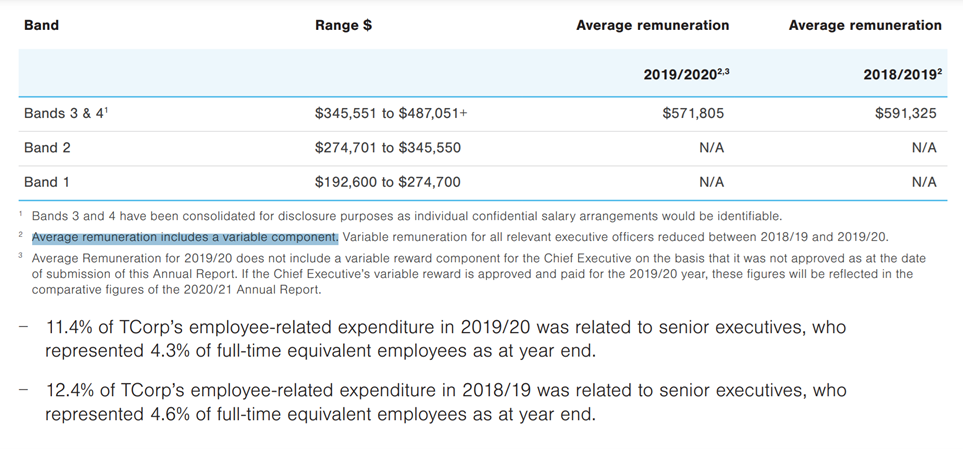

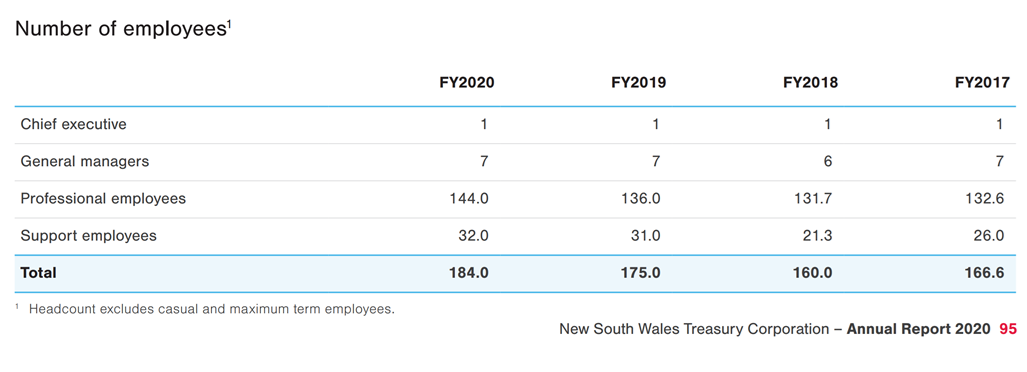

3. NSW Treasury Corporation (TCorp) is a for-profit entity that discloses in its Annual Report key performance indicators including its profitability, which was $75 million in 2020, and its funds under management, which were $103 billion in 2020. TCorp says that its "funds management volumes increase to over $100bn, placing TCorp in the top five asset managers in Australia and within the top 100 globally". One of TCorp's main sources of revenue is "investment management fees", which totalled $85 million in 2020. In funds management, these fees are normally based on the value of funds under management. TCorp's discloses that its 184 employees were paid total compensation in 2020 of $53.7 million, which implies average total compensation is circa $292,000 per employee. TCorp is also responsible for raising and managing the issuance of all NSW government debt. So TCorp raises the debt for NSW and is then paid by NSW to manage the money. My key questions are (1) whether TCorp is paid higher investment management fees as FUM increases, (2) whether TCorp executives are compensated partly based on TCorp's profitability through either base salaries and/or bonuses, and (3) whether TCorp executives therefore have a financial incentive to convince NSW to keep directing money into the NGF and not to use that money to payback debt and/or fund new infrastructure?

The key screenshots relevant to these questions are illustrated below from the 2020 TCorp Annual Report.

Under the NGF's Act, the DRF can only use its money to repay NSW debt. So it can buy existing NSW government bonds, or TCorp could issue it new NSW government bonds. In this way, it would be extremely easy for the $15bn going to $27bn in the DRF to be used to pay for NSW's fiscal stimulus and help fund the $108.5bn of new infrastructure NSW has proposed.

4. The legislation you enacted governing the NGF and its DRF states quite explicitly that "the purpose of the Debt Retirement Fund is to provide funding for reducing the debt of the State in accordance with the principles of sound financial management set out in section 7 of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2012". If NSW is directing billions of dollars of funding into the DRF that forces NSW to raise many billions of extra gross debt to replace that funding, which is exactly what S&P, CBA and others say you are doing, is that not highly inconsistent with the legislation that requires the DRF to "provide funding for reducing the debt of the State"? How can you possibly reduce the debt of the State by taking on more debt? TCorp and NSW Treasury argue that the DRF can earn "risk premiums" by investing in stocks and illiquid assets. But isn't the "risk" that accompanies this "premium" that the value of these assets fall at the worst possible time (eg, in a recession), as occurred in 2020 when the NGF and the DRF lost money, directly increasing the debt of the State? And with sharemarket valuations at all-time, 100 year highs, and the cost of debt near all-time lows, isn't this the worst possible time in human history to be running an enormous leveraged carry trade?

In an expert report on this topic, Dr Stephen Bartos, the outgoing NSW Parliamentary Budget Officer (he has held this office on the last two occasions it was appointed), and former Deputy Secretary of the Commonwealth Department of Finance & Administration, writes:

This paper finds that there is a reasonable basis to believe that the NSW government is raising debt to invest in the NSW Generation Fund’s Debt Retirement Fund (DRF). Past contributions to the DRF have primarily come from NSW reserves and the proceeds of the sale of 51% of WestConnex. Raising more debt than is required to meet the NSW budget deficit financing requirement appears to be in conflict with the intended purpose of the DRF to reduce the State’s debt.

Although the NSW Budget focuses on net debt, gross debt is an important measure of financial sustainability. Incurring higher levels of gross debt than necessary is a problem for intergenerational equity, exposing future generations to higher risks in the face of adverse interest rate movements. So far the NSW Generations Fund (NGF) has failed to fulfil its intended “dual-purpose” of (1) repaying debt and (2) using up to half of the investment returns to enable the MyCommunity Dividend program. It would appear that only a very small fraction of the NGF’s earnings has been dedicated to community projects. In the current climate of the NSW government running a budget deficit and high levels of debt, a more cautious and prudent risk management approach would be to use the NGF for its intended purpose of reducing debt and funding community projects. I also note that it appears that the cost of NSW government debt is rising because of the sheer quantity of debt that NSW is proposing to issue. As a policy response, it would be straightforward and reasonable for the Treasurer, as the responsible NSW Minister, to clarify that the government does not intend to raise additional borrowings solely for application to the NGF’s DRF...

What appears to be driving this approach is firstly the fact that the funds held by the NGF are classified as an offset to gross NSW government debt, and secondly, that buying equities (assuming this is the intention of further investments in the NGF) while the cost of debt is near record lows is apparently seen as a good trade for taxpayers.

In the year to April 2021 the NGF achieved a return of 15.5% (Budget, Table 6.2, p6- 4), although it lost money in the 2020 financial year as equities performed poorly. While it might on the surface appear attractive for a government to borrow at low interest rates and gamble some, or all, of the proceeds on the stock market to earn higher returns, this approach entails high risk. It is quite common for equity markets to fall by 50% or more (as seen in 1987, 2001, and 2008-09); volatility is one of the defining characteristics of equities markets.

If the value of the NGF falls sharply, this will materially increase NSW’s net debt given that the NGF is currently treated as an offset to NSW government gross debt in the NSW Budget and by the credit rating agencies. It will further raise questions about the ability to use the NGF to repay NSW debt, which could then increase the cost of NSW government debt. This could in turn threaten NSW’s AA+ credit rating from ratings agency Standard and Poors, which was downgraded from AAA in December 2020 because of the large increase in gross government debt...

Levels of debt are already at a record high, not only in NSW but in every Australian jurisdiction, due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. A strategy to reduce fiscal risk would involve lower rather than higher than levels of gross debt. Clearly while the State is in budget deficit it requires borrowing - but a prudent fiscal risk management strategy would be to avoid discretionary increases in new debt. This is particularly so if the increase in debt is applied to investments in equities, a strategy that could amplify fiscal risk in any major downturn...

First, it is important to note that dollars are fungible. A decision to not pay off debt - when that is possible - is equivalent, with minor variations at the margins, to a decision to take on more debt. Placing the WestConnex sale proceeds in the NGF to support NGF investments means those monies are not available to help meet the costs of financing the NSW budget deficit. In cases where a government has net debt, the proceeds from asset sales are commonly used to reduce that debt. Debt reduction has been one of the main justifications advanced for asset sales over the past half century. Not using the WestConnex proceeds to reduce debt is at odds with this normal practice. As an alternative, proceeds from an asset sale may be used to fund new infrastructure, reducing the need for a government to take on new debt. Using the WestConnex proceeds in this way to fund new infrastructure has been foreshadowed by Treasurer, Dominic Perrottet...

That is, use of proceeds from a privatisation like the sale of WestConnex to retire debt would be in line with precedent and would not distort financial markets. The RBA therefore would be unworried about a State using privatisation to rein in excessive debt or to invest in new infrastructure...

It would be straightforward and reasonable for the Treasurer, as the responsible NSW Minister, to clarify that the government does not intend to raise additional borrowings solely for application to the NGF’s DRF. It would also be possible for the Treasurer to reaffirm that the intention with the proceeds from the sale of the State’s remaining interest in WestConnex is to invest in new infrastructure, reducing the need to take on additional debt for the government’s proposed new infrastructure projects. Both decisions would materially reduce the fiscal risk the State faces, and that which confronts future generations. They would also likely be welcomed by investors, reassure ratings agencies, and thereby reduce the cost of NSW’s debt servicing obligations

5. Once again, in the legislation you enacted governing the DRF, it says that "the purpose of the Debt Retirement Fund is to provide funding for reducing the debt of the State in accordance with the principles of sound financial management set out in section 7 of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2012".

The principles in Section 7 of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2012 exist to serve the Act's "object", which is outlined in Section 3 of the Act, which says:

The object of this Act is to maintain the AAA credit rating of the State of New South Wales.

In December 2020, NSW lost its AAA credit rating with the main global credit rating agency, Standard & Poor’s, because of the increase in its gross debt issuance. NSW is now rated AA+ by S&P. S&P wrote that they downgraded NSW because they “expect an upsurge in gross public debt over the next three years”. “The downgrade primarily reflects our expectation that NSW's debt burden will rise substantially during the next three years,” S&P wrote.

By increasing the gross debt of NSW to provide funding to the NGF's DRF, you are directly undermining NSW's credit rating, and reducing the probability of winning the AAA rating back, in conflict with the NGF's legislative requirements.

More specifically, one of the key credit rating metrics S&P uses is NSW's interest repayments on its gross debt relative to NSW's operating revenue. As debt surges, interest repayments increase, directly reducing the quality of this metric, and hence NSW's rating integrity.

Further, the "purpose" of the Object of the Act is to "limit the cost of government borrowing", which NSW has directly increased due to the debt funding surprises associated with the NGF, as the chart above shows. The chart below shows NSW's cost of debt relative to all the other State governments as a spread above the interest rate paid by the Commonwealth government.

You can see that NSW now has the highest cost of capital of all the States. Since May 2021, just before the NSW budget was released, NSW's cost of debt has increased by more than 0.20%, or by more than 20 basis points, when borrowing its benchmark 10 year money. Across the more than $100 billion that NSW owes, this represents an extra $200 million a year in annual interest on the new debt it raises as the old debt is replaced.

According to CBA, NSW has disclosed proposed investments in "financial assets" worth some $19.2 billion in this financial year and the following three years. In this year alone, investments in financial assets sum to $7.2 billion based on CBA's numbers. You can see these commitments as the black segments in the bar chart below. I added-in the blue text and arrow showing the black segments.

6. The NSW Budget, and TCorp and NSW Treasury officials, all claim that the NGF's DRF is "reducing net debt" and acting as a "offset to debt". Yet because the NSW budget is running large deficits, and the investments NSW is making in the NGF's DRF take cash-flow away from the budget, NSW has to increase gross debt to replace the billions of dollars of cash-flow that is lost when it is directed to the NGF. As S&P and others have explained, this means that NSW contributions to the NGF are paradoxically increasing NSW's gross debt, and not reducing net debt. Assuming that all the money put into the NGF is only invested in "liquid financial assets", which it is not (there are substantial investments in "illiquid" assets), then gross debt increases, but net debt does not increase or decrease (ie, net debt is unchanged). Of course, if the NGF does invest any money in "illiquids", then net debt actually rises, because S&P has made it clear in its latest report on the NGF that it will hair-cut any illiquids. So how can NSW claim that the NGF is reducing net debt? The only basis on which NSW can make this claim is on the hope that the NGF's bets pay-off, and do not decline, as they will in all serious downturns/recessions (and they did in 2020).

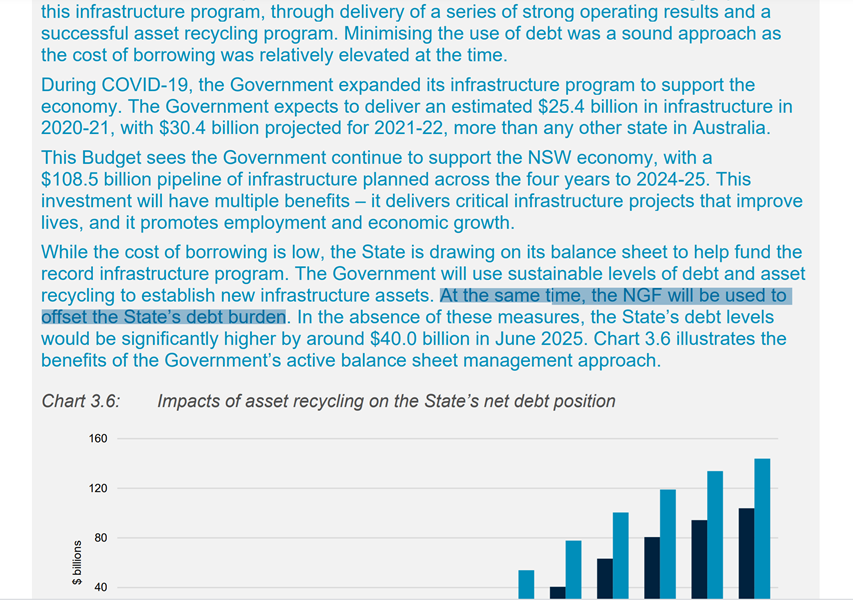

See some screenshots from the latest NSW budget below on the NGF acting as a debt offset, or helping reduce net debt.

7. The NGF was designed to reduce debt and fiscal risk. But as S&P and the big banks have noted, by investing most of the NGF in equities and other high-risk "alternative" asset-classes, the impact of the NGF is to increase, not decrease, fiscal risk. In all downturns, the NGF's assets will likely fall in value, and the net debt of NSW will rise, as occurred in 2020, at the worst possible time. This pro-cyclicality inherent in the NGF is amplified by the NSW government massively increasing gross debt just to be able to direct funds into the NGF: NSW is leveraging-up its balance-sheet to be able to punt on what is a levered "carry trade" where NSW hopes the returns beat the risks of the strategy. Yet if this strategy was sane or sensible, why wouldn't every government throughout the world just issue as much debt as they could and gamble that money on stocks and global financial markets in the hope that they win, not lose?

In a detailed report on this topic, CBA's strategists comment that “as time passes, most of the NGF balance is actually going to be the annual contributions , however, not the original seed funding”. CBA confirms, as other banks have done, that “these flows increase gross debt and make no impact on net debt” . As noted above, this is contrary to NSW and TCorp’s claims that contributions from NSW into the NGF reduce net debt. CBA further comments:

“The increase in gross debt comes about because of what the cash is not spent on. In the absence of the NGF, these inflows might have been spent on something else – for example Capex [NSW has $108.5bn of capex commitments in its Budget].”

“In any world without the NGF, NSW would have used to defray the cost of Capex investment. Instead, the NSW government is investing in the NGF and having to borrow the full cost of the Capex. The net result is a grossing up of the NSW balance sheet. The NSW government has both more debt (in the form of borrowing) and more assets (in the NGF’s ).”

A diplomatic CBA warns that this leveraged equity carry trade carries risks:

“At present, the cost of NSW borrowing is well below the…the NGF’s target performance…For the moment the interest costs are very low, but this may be an issue in time if interest rates rise (or investment returns fall).”

CBA concludes as follows:

“For any other State, an operating surplus indicates that no borrowing is necessary – but this is not true of NSW. NSW can run an operating budget surplus (indeed, in theory even a fiscal surplus) and still need to borrow money to cover the investments pledged to the NGF…The structure of the NSW policy intentions regarding the NGF – at present – means that gross borrowing will continue to grow and continue to provide .”

8. NSW Treasury and TCorp officials have claimed that the NGF boosts "intergenerational equity" . Yet taking on massive amounts of debt today, and risking that money in stocks, hedge funds, private equity, and other volatile asset-classes, is both fiscally irresponsible and directly counter to the interests of all future taxpayers in any serious downside scenario. Does NSW believe there could be scenarios in which interest rates rise and equity valuations decline that in turn materially reduce intergenerational equity?

In an expert report on this topic, Dr Stephen Bartos addresses the question of intergenerational equity:

The risks associated with borrowing to purchase equities, discussed previously, affect not only the current fiscal position but also future generations. While it is impossible to predict peaks and troughs in share markets , severe downturns involving losses of 50% or more happen periodically (for example, in 1987, 2001, 2008-09) as do smaller yet still very significant falls. They are inevitable even if their timing cannot be predicted.

When a downturn happens, future generations will be more exposed to fiscal risk than they would have been had the NSW government not taken on additional borrowings to invest in the NGF.

The rapid rise in gross NSW debt is also an issue for intergenerational equity. The NSW Intergenerational Report of June 2021 highlights that gross debt is growing faster than net debt over the period to 2060-61. The difference is primarily due to the investments made into and by the NSW Generations Fund. The NGF is a “net offset” against gross debt, although it may become increasingly difficult for NSW to liquidate its assets in an orderly fashion to repay debt simply because of the sheer size of its investments, some of which could become illiquid...

Net debt provides a potentially more accurate picture of the State’s fiscal position than gross debt, if the underlying assets can be valued properly, and is therefore important to measure and report. However, as previously noted, gross debt is also an important measure of fiscal sustainability, which crucially credit rating agencies assess in addition to net debt, and increased gross debt is a source of risk.

In terms of intergenerational equity, use of borrowing to fund the NGF means future generations are exposed to a higher level of risk of adverse interest rate movements than are current generations.

Raising increased debt also increases the cost of borrowings. This has already been observed in relation to the cost of NSW debt, which (based on publicly available financial market data) has become the highest of all Australian States.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

3 topics