2 corporate failures and the hidden benefits of indexing

Betashares

This article was written by Benjamin Cahill

In 1965, companies in the S&P 500 index stayed in the index for an average of 33 years. By 1990, that figure had dropped to 20 years. At the current churn rate, about half of today’s S&P 500 firms will be replaced over the next 10 years.1

There are many reasons why companies go backwards or fail. One of the more obvious reasons is the inability for companies to adapt to the changing environments in which they operate.

As the famous biologist, Charles Darwin, stated;

“It is not the most intellectual of the species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; but the species that survives is the one that is able best to adapt and adjust to the changing environment in which it finds itself.”

While this quote was originally in relation to species, there should be no doubt about the relevance and application to the evolution of companies. Below are two informative examples of companies that ultimately failed to respond to their changing environment, as well as the hidden benefit of index investing.

KODAK

Kodak was founded 130 years ago in 1892 and was at one point in time the world’s most valuable film company. Its value peaked in 1997, valued at a staggering US$30B (US$54B adjusted for inflation). In the mid to late 20th century, they effectively held a monopoly on the sales of cameras and film, with more than 75% global market share.2 But in January 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy. So, where did it all go wrong?

Figure 1: (L) Vintage Kodak Ad 1952 (R) Vintage Kodak Ad 1950. (Source: Envisioning the American Dream)

Kodak’s business revolved around the repeat sales of film for their cameras. Known as the Razor-and-Blades business model, they would sell the camera itself at a low margin and would sell the consumable, the film, at a high margin. All was well until the digital shift began, marked by invention of portable digital cameras in 1975.

But this shouldn’t have been an issue for Kodak! Steve Sasson, at the time an electrical engineer for Kodak, was the inventor of the first portable digital camera – which the business promptly patented. At the time, the economies of scale were not beneficial to make the shift to digital as cameras cost thousands of dollars and the quality was still questionable.

The main issue was that, for the next 20 years, Kodak’s invention remained on the shelf as management struggled to shift their thinking and strategy to accommodate for the digital era. Kodak was making so much money from film that their technology gathered dust, with management fearing they would cannibalise their film business by shifting to digital.

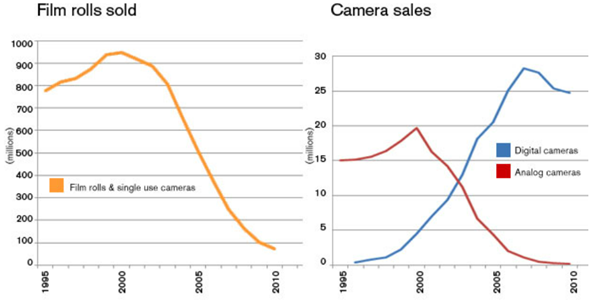

Within five years of their original patent expiring, sales of film rolls and analog cameras had peaked. Meanwhile, digital camera sales had grown more than 500%.3

Figure 2: Film rolls and camera sales. (Source: Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Art3)

Digital photos are cheaper to produce and higher quality than film. Kodak failed to realise that their business model and near monopoly on photography, were at risk from rapidly changing technology.

Once a phrase synonymous with a moment worth capturing, a Kodak Moment now commonly represents a business’s failure to foresee.

BLOCKBUSTER

Many can reminisce of the days of heading down to the local Blockbuster, arguing with family and friends over which movie to select before heading home, plonking on the couch and hushing everyone as the movie began. Unfortunately, we are unlikely to get this experience again.

The 1990s was the time of the VHS. Adjusted for inflation, movies were regularly retailing for US$100, even US$150 each.

Late fees aside, Blockbuster was the perfect solution for the problem, allowing customers to rent movies at a fraction of the cost. The business model was logical. Blockbuster eventually turned into a global powerhouse, employing 84,300 people across 9,094 stores at its peak.4

On the eve of the 21st century, the digital shift was in full swing. The technological change underway began to favour DVD rentals, and later streaming services, as the new medium for at-home video entertainment.

In 1997 Netflix was founded and their core business revolved around online DVD rentals, and later streaming. Blockbuster had the chance to buy Netflix in 2000 for US$50M (US$84M adjusted for inflation), but allegedly laughed the up-and-coming business out of their office.5

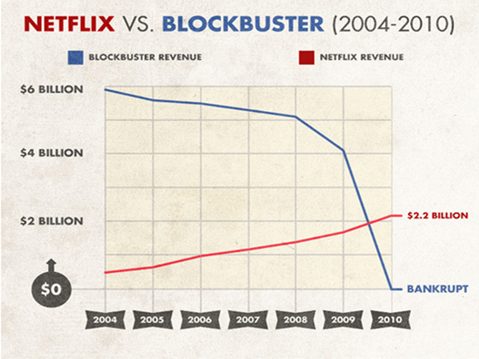

Blockbuster instead followed suit, launching their own Netflix-like service in 2004. By 2006, Netflix had 6.3 million subscribers versus 2 million for Blockbuster.6 Netflix had a 7-year head start, but Blockbuster had a globally recognisable brand. It was anyone’s game.

But here’s where the blunder happened.

In 2006, famous activist-investor Carl Icahn staged a proxy-vote to remove the then-CEO, John Antioco, who was focused on this digital shift. The vote passed and James Keyes, who had a background running the bricks-and-mortar business 7-Eleven, took position as CEO. Both Icahn and Keyes believed re-investing in retail stores was the best move for the heavily indebted Blockbuster, and subsequently halted the digital shift in its tracks. Deciding to stay with an outdated business model proved fatal for Blockbuster.

“I’ve been frankly confused by this fascination that everybody has with Netflix… Netflix doesn’t really have or do anything that we can’t or don’t already do ourselves,” said Keyes in 2008.

Two years later Blockbuster’s share price had fallen more than 80%, and a shortly after that, it filed for bankruptcy. In March 2022, Netflix was worth US$200B and had more than 220 million active subscribers.7

Figure 3: Netflix vs Blockbuster Revenue. (Source: HBS ‘Blockbuster: It’s Failure and Lessons to Digital Transformers’)

What’s the lesson?

Many companies fail because they don’t evolve, but there’s also a hidden lesson relevant to index investing. The idea of holding only the top 100, 200 or 500 companies within a given market have greater implications than what meets the eye. For example, only ~10% of companies that were in the S&P 500 in 1955 remain in the index, with the other 90% either failing, merging or falling out of the top 500.8

But, if you had invested US$100 in the S&P 500 Index in 1955, it would be worth more than US$80,000* today in nominal terms.9 How does that work? As companies come and go, broad-market indices adhere to Charles Darwin’s quote, and systematically evolve with shifts in market dynamics, the introduction of new ideas and the companies at the forefront of change.

*Note: You cannot invest directly in an index, and the investment return shown does not take into account any fund management fees and costs. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.

Follow for more insights

If you enjoyed this wire, don't forget to give it a 'like' or leave a comment. To be the first to read my insights, hit the follow button below.

Trusted by hundreds of thousands of Australian investors, BetaShares offers cost-effective, simple, and liquid access to the broadest range of ETF investment solutions available on the ASX, covering almost every asset class and investment strategy.

Information has generally been sourced from the following:

1. Snively, C., & Raffaelli, R. (2018). The Reinvention of Kodak. HBS CASE COLLECTION

2. Sloan, M. (2020, June 1). Netflix vs Blockbuster. Retrieved from Drift: (VIEW LINK)

Footnotes

1. Perry, M. J. (2021, June 6). Creative Destruction. Retrieved from AEI: (VIEW LINK)

2. Snively, C., & Raffaelli, R. (2018). The Reinvention of Kodak. HBS CASE COLLECTION.

3. Chistiakova, I., Chui, T., Favarin, A., Papamichali, M., & Pataut, P. (2017). The ‘Kodak Moment’ is Dead. Long Live Kodak! Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Art.

4. Google Arts and Culture. (2022, June 30). Blockbuster LLC. Retrieved from Google Arts and Culture: (VIEW LINK)

5. Graser, M. (2013, November 12). Epic Fail: How Blockbuster Could Have Owned Netflix. Retrieved from Variety: (VIEW LINK)

6. Sloan, M. (2020, June 1). Netflix vs Blockbuster. Retrieved from Drift: (VIEW LINK)

7. Statista. (2022, April 1). Netflix paid subscribers worldwide. Retrieved from Statista: (VIEW LINK)

8. Perry, M. J. (2021, June 6). Creative Destruction. Retrieved from AEI: (VIEW LINK)

9. Webster, I. (2022, June 30). Stock market returns since 1955. Retrieved from OfficalData.org: (VIEW LINK)

4 topics

Patrick is the Editorial Director at Betashares and a member of the Investment Strategy and Research Team. He has over 15 years of finance and financial media experience with past roles at Livewire, netwealth, Link Group, and others.

Expertise

Patrick is the Editorial Director at Betashares and a member of the Investment Strategy and Research Team. He has over 15 years of finance and financial media experience with past roles at Livewire, netwealth, Link Group, and others.