Cheap stocks, and how to buy them

People often refer to themselves as either “fundamental” or “technical” investors and feel so strongly about one style of investing compared to another that they engage in heated academic debates. The view at Cadence Capital is that investors should use whatever tools are at their disposal to try to beat the market and that fundamental analysis combined with technical analysis has a greater probability of achieving that than one style alone.

Understanding fundamental analysis

When we refer to fundamental analysis, we mean the process of determining accounting profits, operating cash flows, free cash flows, balance sheet debt, cash and overall balance sheet strength, as well as estimating numbers for these metrics two years into the future.

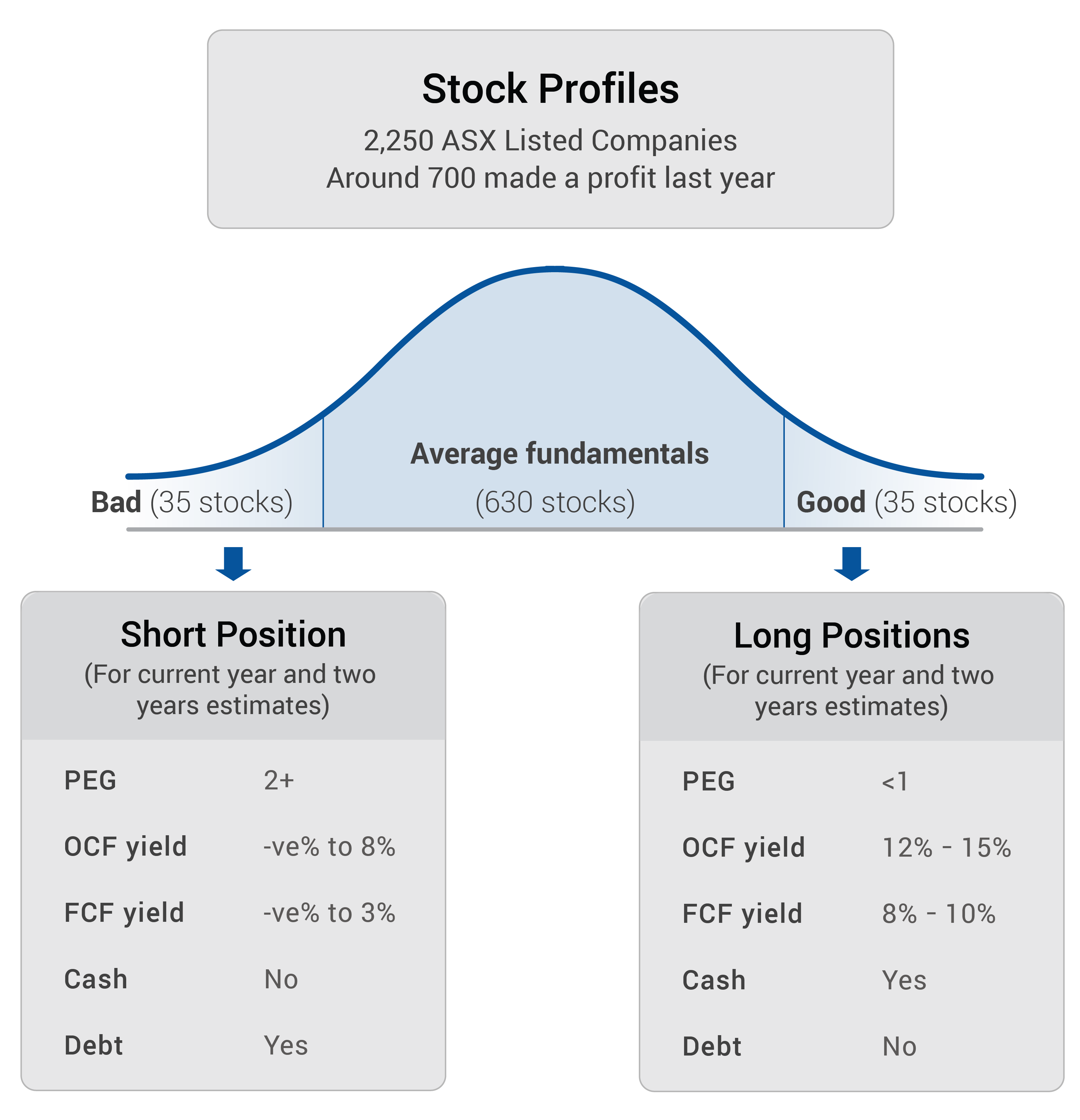

There are about 2,250 stocks listed in Australia (2.5 percent of the world’s listed market capitalisation) and in any given year 600 to 700 of these companies actually make a profit – so about 75 per cent of Australia’s listed companies do not.

We are unable to analyse companies that do not make a profit, so we are restricted to choosing from roughly 700 companies a year to add to our core portfolio.

Of these, 5 percent are usually cheap, and 5 percent are really expensive in any given year. This equates to a “sweet spot” of about 70 companies that meet our fundamental criteria. We hope to construct a portfolio of between 30 and 40 core positions in any given year.

This approach is outlined in Diagram 1 below. Importantly, since we believe there are only 70 really good opportunities in any given year, we need to have an open mandate to implement this investment strategy (that is, fewer restrictions on the fund’s investment style). Investing with an open mandate is unusual in Australia and particularly in the superannuation investment industry.

We estimate that around 85 percent of all superannuation money invested in Australia is invested on a restricted mandate, effectively reducing the number of really good opportunities available to a portfolio manager.

Investment managers spend much time looking for companies that meet their fundamental criteria. Cadence visits 300 to 400 companies a year trying to find stocks it can add to its core portfolio.

Diagram 1 shows that a typically cheap stock may have:

- Earnings growth of around 20 percent per annum.

- A price-to-growth (PEG) ratio of more less than one.

- Price-to-earnings (PE) multiple of around ten times.

- 12 to 15 percent operating cash flow (OCF) yield.

- 8 to 10 per cent free cash flow (FCF) yield.

- Minimal debt on the balance sheet.

- (A ‘long position’ means the fund will buy that stock).

Conversely, an expensive stock may have or be:

- Growing at 10 percent per annum.

- A price-to-growth (PEG) ratio of more than two times.

- Trading on a PE multiple of 20 times.

- Negative to 3 percent operating cash flow.

- Negative to 3 percent free cash flow yield.

- Lots of debt on the balance sheet.

- No cash.

- (A ‘short position’ means the fund will sell that stock).

The process of trying to identify cheap and expensive stocks is ongoing, and just as individual stocks exhibit cyclical earnings and valuations, so too does the overall sharemarket.

At the time of writing, several sectors in the market are showing high valuations, and a smaller, more discrete, group of stocks are actually presenting as fundamentally cheap. This is often the case.

Using technical analysis

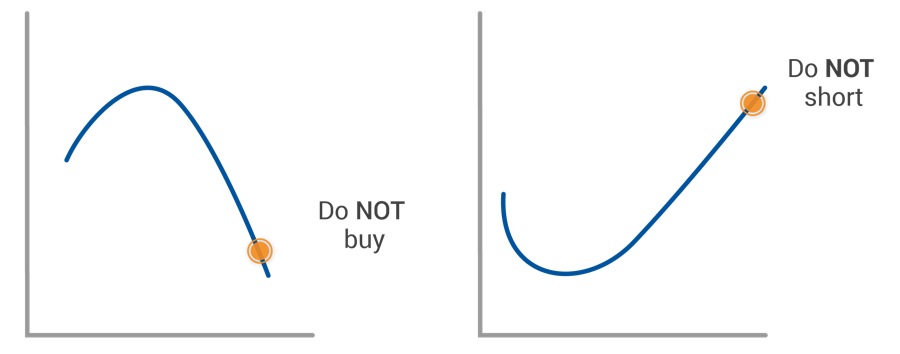

Diagram 2 below shows that no matter how cheap we think a stock is, we are not allowed to buy if it is falling in price or in a downward trend. Conversely, no matter how expensive a stock, we do not sell or short-sell if it is in a share-price uptrend.

Buying stocks that are falling and selling stocks that are going up are probably the two biggest mistakes that investors make. There are deeply ingrained reasons for this and many psychological barriers within investors’ psyche that often prevent them from buying stocks that are going up and selling stocks that are going down.

In fact, investors are often compelled to do exactly the opposite. Books on this aspect of behavioural investment make very good reading.

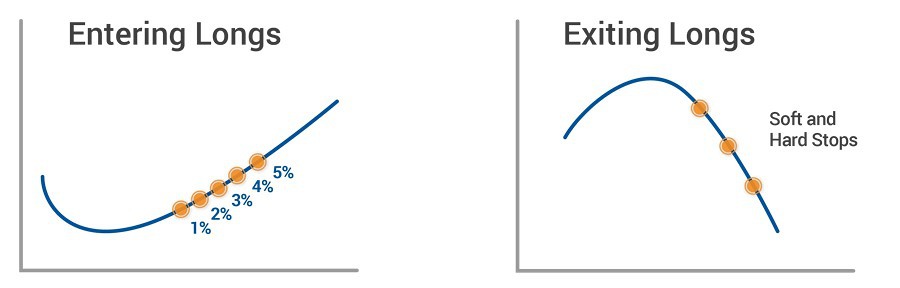

An entry strategy to buy cheap stocks

Diagram 3, below, shows the process that Cadence undertakes once it has identified a stock to be cheap. We wait for the falling share price trend to finish (this is how a stock becomes cheap – people sell it). Once the price starts to recover, we initiate a 1 percent position. At this point, conditions are ideal for generating good risk-adjusted returns. We then add 1 percent and another 1 percent as the price rises, up to a maximum of 5 percent of our portfolio at cost into any one position.

Our core positions start as 1 per cent positions initially, so we do not have too much capital invested in any one new idea. Starting with a small position is another way of mitigating risk.

Diagram 3 also shows how we exit our positions once the long-term trend has ended and the stock becomes expensive. We sell a third of the position initially then another third and eventually the final third. In this way, we are not making decisions about an entire position on a day-to-day basis.

The Fundamental and Technical Process in Practice

Diagram 4, below, shows the combination of fundamental and technical analysis operating together with one of our fund’s current positions, Macquarie Group Limited.

Shortly after reaching a peak of nearly $100 (on our fundamental analysis at the time, reasonably expensive), the GFC brought havoc to the global financial system, and Macquarie’s earnings fell substantially, along with its share price.

It kept falling and at around $40 started to look reasonably cheap from a fundamental perspective. However, as outlined, we were not compelled to buy a stock that was cheap but still falling in price.

Macquarie subsequently traded as low as around $17 and then recovered, to its current price of around $60 ($64 if you include the recent spin-off of Sydney Airports). Once the fundamental and technical picture for Macquarie lined up (that is, the stock was fundamentally cheap and technically going up), we started buying with an initial 1 percent position at $23, then added to it again around $26, $28, $35 and $41, accumulating a 5 percent position, at cost, over time.

In this example, had we started buying when we identified Macquarie as fundamentally cheap when the share price was still falling, we would have been taking unnecessary risk and incurred large losses before the stock price actually finished falling and began to rise.

From a fundamental perspective, it does not matter how cheap or expensive investors may think a stock is, should the share price still be falling it is not a good time to buy technically, and should the share price still be rising, it is not a good time to sell technically.

Using a combination of both fundamental and technical analysis investing into Macquarie has delivered good returns, but more importantly good risk-adjusted returns, assisting us in determining when to buy and sell Macquarie Group.

4 topics

1 stock mentioned