5 grey swans that could disrupt markets in 2022

At State Street Global Advisors, we establish a base case

that incorporates the dynamics we see as most likely —

our Global Market Outlook captures what we expect

to see as 2022 unfolds. But acknowledging that things

don’t always turn out as expected is also important

— COVID-19 is not the only left-field event in recent

decades. There is always scope to consider alternative

scenarios that have a reasonable, if low, probability of

occurring. We call these scenarios Grey Swans.

Thinking about Grey Swans helps inform the risk-aware approaches we take across our portfolios. The market may discount their likelihood, but each one has the potential to materially move markets. We recommend that investors regularly evaluate whether they are adequately protected against tail risks.

Lori Heinel, Global Chief Investment Officer, SSGA

1. Peripheral Europe drives returns… and unity?

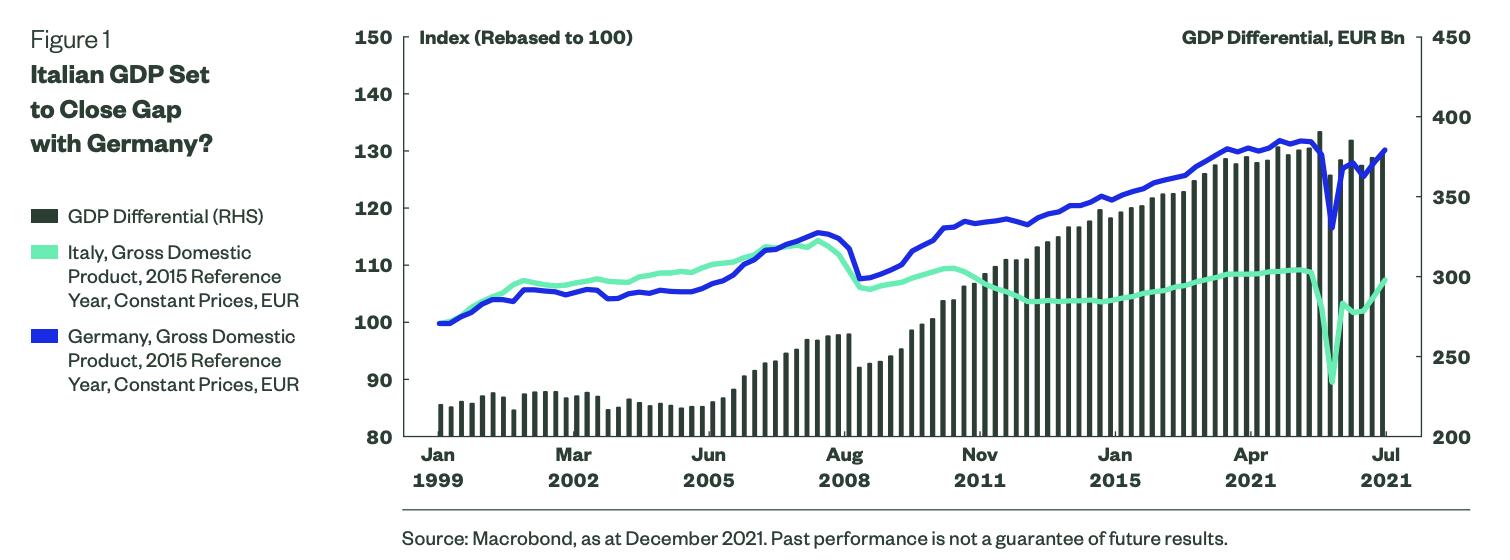

Aspirations for an ever-closer union have for a long time seemed just that — aspirational. Instead of convergence we’ve had divergence, with the disparities between the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ laid bare during and since the credit crisis of a decade ago. But could the green-tilted Recovery Fund for the worst-hit euro area countries be the catalyst that ultimately transforms the narrative in Europe?

Italy and Germany’s relative economic trajectories in recent decades have been a sore point as heavily indebted Italy failed to make up a growing productivity gap with a globally focused German industrial powerhouse. But in this Grey Swan, the scale of stimulus deployed in Italy lifts the economy to the extent that growth there (and elsewhere in the periphery) outpaces that of Germany and the core and bolsters support for greater fiscal union. Growing corporate investment and buoyant sentiment in and towards Italy drive relative bond outperformance amid a sharp narrowing of bond spreads with Germany.

Amid recognition that the union is running out of fiscal and monetary road at a time when the region’s potential output and productivity trends have been left trailing the US and China, a consensus forms around the need to facilitate a more dynamic private sector that is backed by abundant and accessible public and private financing. For example, a well-funded private sector that can navigate new and disruptive technologies enhances the success potential of the EU Green Deal.

Taking the political leap of faith necessary for the eurozone to transition to a genuinely viable, independent and globally competitive entity, the more ‘frugal’ European states such as Germany and the Netherlands find common ground with the likes of Italy and France. All sides shift from long-entrenched positions, such as on banking union. This is not an overnight fix, but the eurozone getting on this path sets in motion a virtuous cycle.

From a top-down perspective, the euro gets put on a sound footing with deposit insurance and the mutualisation of debt.

But bottom-up suddenly comes into focus with new and greater incentives for savings to find their way into equity investment. Plans are brought to the fore for a single capital market to make way for equity financing and to broaden out investor choice. The supply side is overhauled with an agenda to simplify and reduce regulation and taxation.

For investors, the appearance of sustainably higher output growth materializing could drive a true re-rating of the eurozone equity market, underpinning outsized return potential. But the real transformation may be seen in the fixed income market where spreads could tighten, and consolidate at low levels, making Italian and peripheral debt less speculative. Against this backdrop, the euro would also strengthen considerably.

2. Crypto regulation spawns spillover risk

The sustained surge in cryptocurrency prices through much of the last two years has coincided with more widespread acceptance of digital assets. The broadening out of the digital asset market to include so-called meme tokens such as Dogecoin, as well as the rise of the NFT (non-fungible token), has not only attracted great media interest but also wealth. The market cap of cryptocurrencies is around $2 trillion (1), which is greater than each of four S&P 500 sectors (Utilities, Materials, Real Estate and Energy) (2).

Investment-related products have also launched in the past year, and more are being filed with regulators. This has allowed retail and institutional investors to include cryptocurrency exposure within portfolios even as oversight remains scant.

In this Grey Swan, a burgeoning chorus of demands for regulation of digital assets sets in motion a market correction, one that spills over into traditional markets, given the increased usage among consumers that has translated into elevated ‘paper’ wealth. And there are already straws in the digital wind for such action.

In December 2021, the US House Committee on Financial Services hosted a hearing on cryptocurrencies and financial technology on the heels of a Treasury Department report on stablecoins — regulators are increasingly focused on the impact of decentralised finance applications and digital assets on the economy and consumers. This has already resulted in the US government making provisions for cryptocurrency taxes in the recent infrastructure legislation — previous efforts regarding cryptocurrency regulation had stalled in Congress.

Given rising retail investor involvement and the sizeable increase in hacks of both cryptocurrencies and NFTs, demands that consumers be properly protected can be expected to grow on the grounds that the ‘retail user’ is neither sophisticated enough nor aware of the inherent risks in owning ‘glamour’ jpeg digital assets. $11 billion in NFT sales took place in Q3 2021 (3) —NFTs have become so mainstream that Macy’s offered them for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade (4).

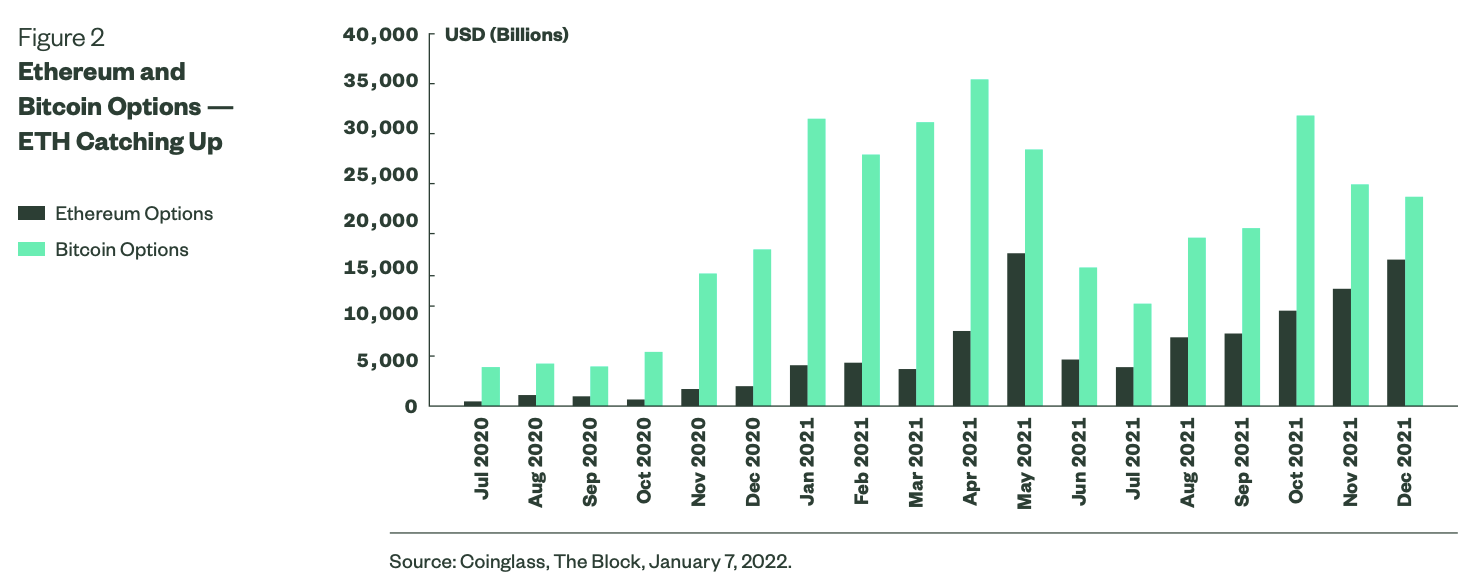

But NFTs are not the only digital-related assets on the rise. Data from Crypto Compare shows that derivatives’ trading volume for the cryptocurrency market exceeded spot market volumes in June for the first time (5). And in November, derivatives volumes hit a record high of $3.2 trillion before falling back to $2.9 trillion in December — this accounts for about 53% of the total crypto market (6). Furthermore, combined trading volume of Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH) options increased 443% in 2021, according to The Block Research (7).

As illustrated in Figure 2, ETH option

volumes are getting closer to the more established Bitcoin.

Heightened regulation should lead to an overall reduction in risk and speculation. And if there was

a dash for the exits in the digital world, the sheer size and scale of the digital asset market poses

contagion risk. As digital asset valuations decline, capital would need to be raised to preserve

wealth or meet capital calls on the derivatives, and traditional assets would likely be the first

choice in terms of meeting liquidity needs and de-risking.

3. Central banks caught behind the curve

US Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell recently stated that “it’s probably a good time to retire that word ,” relating to inflation. With that comment came an acceleration of the trends that had already been forming in the fixed income space. US short-term interest rates moved higher in anticipation of the Fed quickening the pace of policy rate hikes (to an expected three 25bps hikes in 2022). Longer-term interest rates (10-year Treasury yields) remained anchored at around 1.5% as markets appeared happy about the signal that the Fed would not let inflation get out of hand.

This bear flattening of the yield curve is a typical occurrence in the expansionary phase of the business cycle where growth remains above trend, prices are moving higher and the central bank is set to remove accommodation in response. But what if inflation has already become ingrained in the psyche of consumers and producers? And, despite the recent shift in tone, what happens if the central banks remain too far behind the curve? What if the markets lose faith and long-term yields rise substantially, bucking the current trends?

Inflation and interest rates remain the key macro risk in markets today. Bond prices fall as interest rates rise, but the impact today may be much broader than that. The entire capital market structure could be troubled as lofty valuations in many segments of the market have often been justified by the low and stable inflation and interest rate environment that has persisted for much of the last two decades.

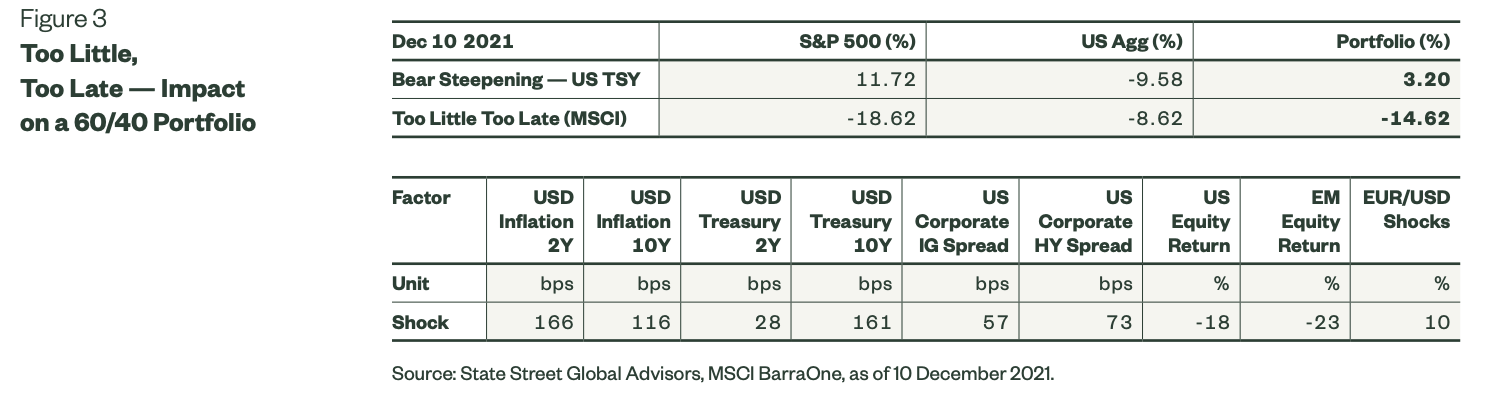

This environment is not one that market participants in developed markets have experienced in the last several decades and many are likely ill-prepared. In this Grey Swan, markets perceive that the policy path is too slow, which brings inflation worries to the forefront. While short-term growth is steady, long-term forecasts are hit. Higher inflation and a diminished growth outlook increase equity risk premia. Equities decline while long-term interest rates pick up, resulting in a positive bond-equity correlation.

Figure 3 outlines the impact on a 60/40 equity/bond portfolio of the Too Little, Too Late scenario.

This shock analysis is based on interest rates being increased by 200 basis points. Most

traditional portfolios would suffer greatly in these conditions as bond prices and equity multiples

would likely decline at the same time. But there are some assets that would likely do better. Real

assets are likely to fare relatively well. Value stocks would likely outperform growth stocks. And

cash is king in an environment where everything sells off.

Investors should not ignore the potential for this scenario to unfold, however low its probability.

Stress-testing portfolios allows investors to make plans for how to manage through such an

event and potentially re-orient towards areas of the market that can shield them from the

worst outcomes.

4. Oil Hits $150

Higher energy prices function as a tax on consumers and businesses, reducing growth and earnings expectations, while their inflationary impact introduces risk of higher interest rates and greater monetary policy uncertainty. Slower growth and higher inflation are an unwelcome combination that substantially increases downside risk and volatility in equities, credit, and currency markets. And such risks tend to weigh more heavily on emerging markets assets as they are sensitive to both rising rates and falling global demand. In this Grey Swan, we consider what could drive oil to $150 per barrel and how investors might protect against such a price spike.

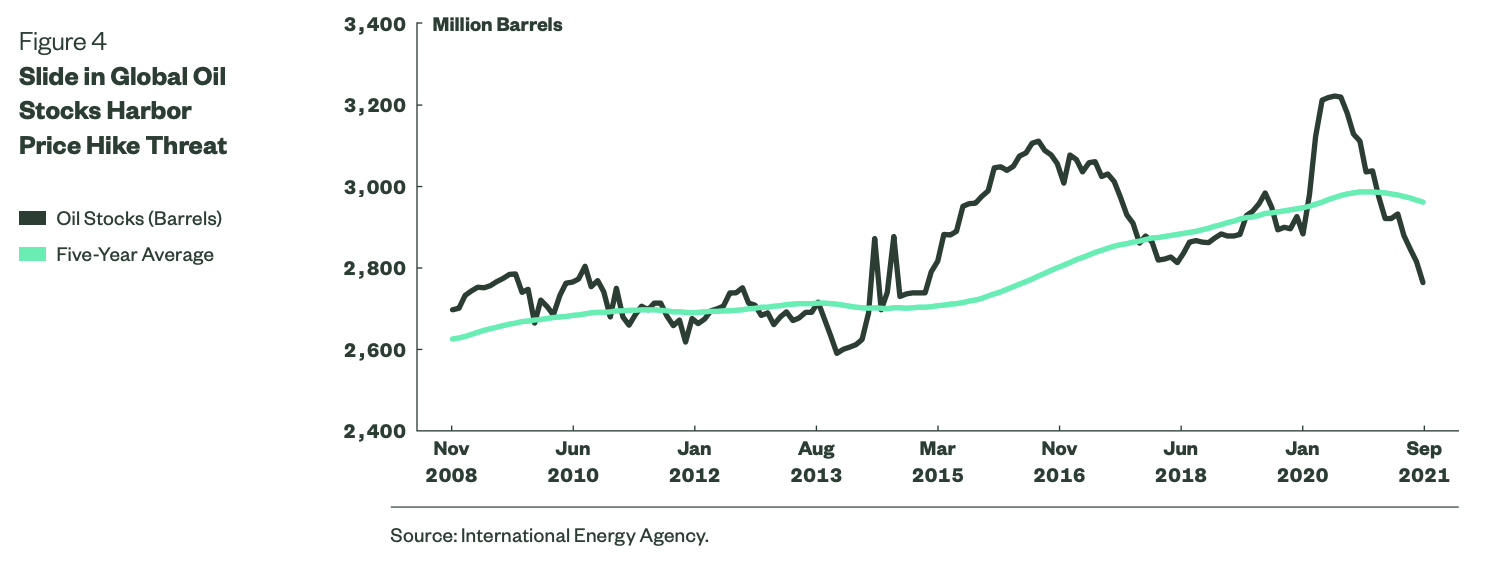

Ultimately this is a supply/demand situation.

Oil inventories in OECD countries are currently at their lowest point since 2015 and are nearly 200m bbls below their five-year average (Figure 4). While the December monthly oil report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicated the potential for a supply increase of 6.4 million barrels per day (mb/d) versus a possible 3.3mb/d demand increase, there are considerable risks to both the demand and supply outlook.

On the demand front, an upside surprise is certainly possible as improved COVID-19 therapeutics and ongoing vaccinations fuel a more complete recovery in consumer demand, business activity, and air travel. Furthermore, global fiscal spending plans call for substantial, energy-intensive infrastructure investment. Conversely, supply could surprise to the downside as many countries cannot reach expected capacity due to poor maintenance and infrastructure as a result of previous capital expenditure cuts — so efforts to boost production could take some time to bring online. According to calculations by Reuters, OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) only managed to increase production by 1.04mb/d from August through November despite pledging to boost production by 1.6mb/d — a 35% shortfall.

US shale has been an important source of additional supply over the past 7 to 10 years. However,

supply is only growing in the Permian basin due to favorable economics — otherwise supply

is actually declining. In total, US oil production was barely changed in 2021 despite rising

consumption growth and higher prices — this leaves it about 10% down from the average of

12.3mb/d achieved in 2019.8

Producers have remained disciplined and continue to focus on

returning value to shareholders.

Against such a tight supply/demand backdrop, any kind of supply shock would send prices higher. On the geopolitical front, heightened risks are evident and could threaten energy supply in 2022. Russia has amassed about 100,000 troops on its border with Ukraine and the G7 has promised “massive consequences” should an invasion follow. Russia’s response would very likely entail severe restrictions on energy exports to the European Union, driving oil and natural gas prices sharply higher. Meanwhile, negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program have thus far been ineffective, and the threat of US or Israeli military action is not out of the question.

How can investors limit the fallout from $150 oil? Inflation and rising energy prices were a large

part of many client conversations in 2021. We continue to recommend that investors re-evaluate

their current positioning and consider dedicating a portion of their portfolio to real assets —

oil and energy provide a direct hedge for this risk. The pullback in prices following news of the

Omicron variant made for relatively more attractive valuations, even if the super-spike scenario

fails to materialize. Over the longer term, we believe a diversified, multi-asset approach may be

best suited to hedge against general inflation risk.

5. Disrupting the status quo: stablecoin goes mainstream

The surge in stablecoin circulation has pushed central banks to consider deploying their own digital assets. While such deployment is likely still some time away, a shorter timetable is not improbable. But in this Grey Swan scenario, a major developed market (DM) central bank takes the leap in 2022 to regulate an off-chain fully collateralized stablecoin, thus bringing it into mainstream finance. Choosing this route instead of issuing a central bank digital currency (CBDC) avoids institutional and policy complexities while promoting blockchain-driven finance — all the encompassing benefits of deploying a digital asset would still apply. Incumbent payment systems will benefit via lower transaction costs, 24/7 trading and instant settlement times.

Akin to any digital asset, end-users should also enjoy safer cyber security and lower barriers to access, maintained on a private-sector infrastructure.

However, regulatory backing should ignite a net boost to stablecoin demand in the short term that would initially disrupt decentralized finance and bring volatility to conventional finance. Regulatory approval would require changes to the operational relationship between stablecoin and existing crypto-assets, and would likely apply an identification requirement (KYC — know your customer). There is scope to mandate the end use of stablecoin and its applicability to existing smart contracts, all of which would initially result in a supply/demand imbalance.

Collateralized stablecoins require large amounts of capital for legitimacy and trust, and their ability to remain stable depends on the underlying collateral. Therefore, the first regulated stablecoin would be fully collateralized by bank deposits and government bonds. In theory, within a closed financial system, this would only have distributional effects as comparable assets move to other balance sheets — overall liquidity should remain the same. The effectiveness of conventional transmission channels for monetary policy could shift, e.g., if either bank deposits or money market funds (MMFs) shrink in favor of stablecoins. Ultimately though, there should not be any major policy impairment as there is no portfolio rotation. Given that the collateral backing stablecoin would be comparable, the overall asset mix in the financial system would remain unchanged.

In practice, however, tokenized coins are even more globalized than conventional finance. The net effect of a first-mover DM-regulated fully collateralized stablecoin would likely see it draw in capital from global markets. While the magnitude may be limited for other DMs, this could be reflected in meaningful capital outflows for emerging markets (EM). The effect would be tightening financial conditions via foreign exchange flows, currency depreciation and higher local bond yields. Given that the first stablecoin would likely be US dollar based, this would exacerbate EM stress and complicate US Federal Reserve policy in the short term.

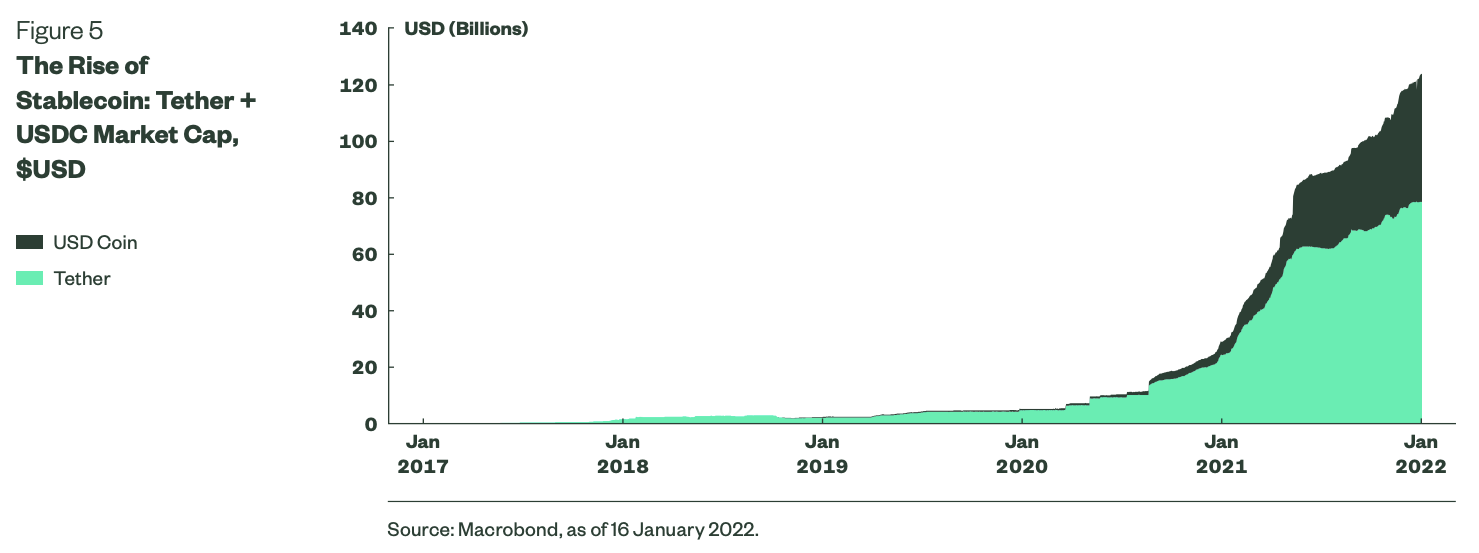

Regulatory approval would also diminish the appeal of existing off-chain stablecoins in the

crypto space that are collateralized by non-government bonds — this is illustrated in Figure 5

where market cap is rising for ‘pure’ stablecoins like USDC (which is pegged 1:1 to the US dollar)

compared to Tether, where reserves hold securities with credit risk. Thus, the introduction of a

regulated legitimate stablecoin could:

- Be highly disruptive to the global payments system;

- Be a major volatility driver within crypto finance;

- Impact conventional safe-haven currencies; and

- Shift global asset flows in the direction of a DM first-mover.

Bonus swan: yield curve inverts in 2022, US recession follows in 2023

Cycles typically last five to seven years, right?

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the average post-war expansion in the United States has lasted just over five years and the last economic expansion persisted for more than 10. This look at history might suggest we are in store for strong asset returns and little risk of recession for several years. But what if the market is missing the warning signals?

There are two main aspects that make this cycle very unusual. First, much of the post-recession recovery phase is about regaining pre-recession peaks in output and lows in unemployment. The output element has already been achieved, while revisiting unemployment lows shouldn’t take much longer either — we anticipate the US unemployment rate to average just 3.7% in Q4 2022. Similarly, wage and salary income took more than two years to make a new peak following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC); in 2020, it took just nine months. With respect to housing, it took about a decade for prices to rescale pre-GFC peaks, but in 2020 housing prices surged as soon as the lockdowns ended. The pure recovery phase of this cycle has been astoundingly short, and the swiftness and intensity of the upswing suggests a shorter duration for the cycle as a whole.

The second aspect relates to the policy response during and after the recession. The extent of policy accommodation, fiscal in particular but also monetary, that has been extended since 2020 has far exceeded historical norms. The cumulative budget deficits for fiscal 2020 and 2021 total about $6 trillion and the Fed balance sheet has increased by $4.5 trillion since March 2020, while the Fed Funds rate has been anchored at 0.00 to 0.25%.

The other side of this coin is a painful withdrawal of policy accommodation. Even with additional support from a scaled-down version of Build Back Better (the recently legislated US infrastructure program), the extent of implicit fiscal consolidation associated with the normalization of fiscal spending is poised to be among the most severe ever recorded. Coupled with a simultaneous tightening of monetary policy and the unpredictability of unusually powerful global inventory cycles, the risks that this combination could bring a premature end to this cycle are non-trivial. Indeed, this could be considered a Swan with a lighter hue of grey.

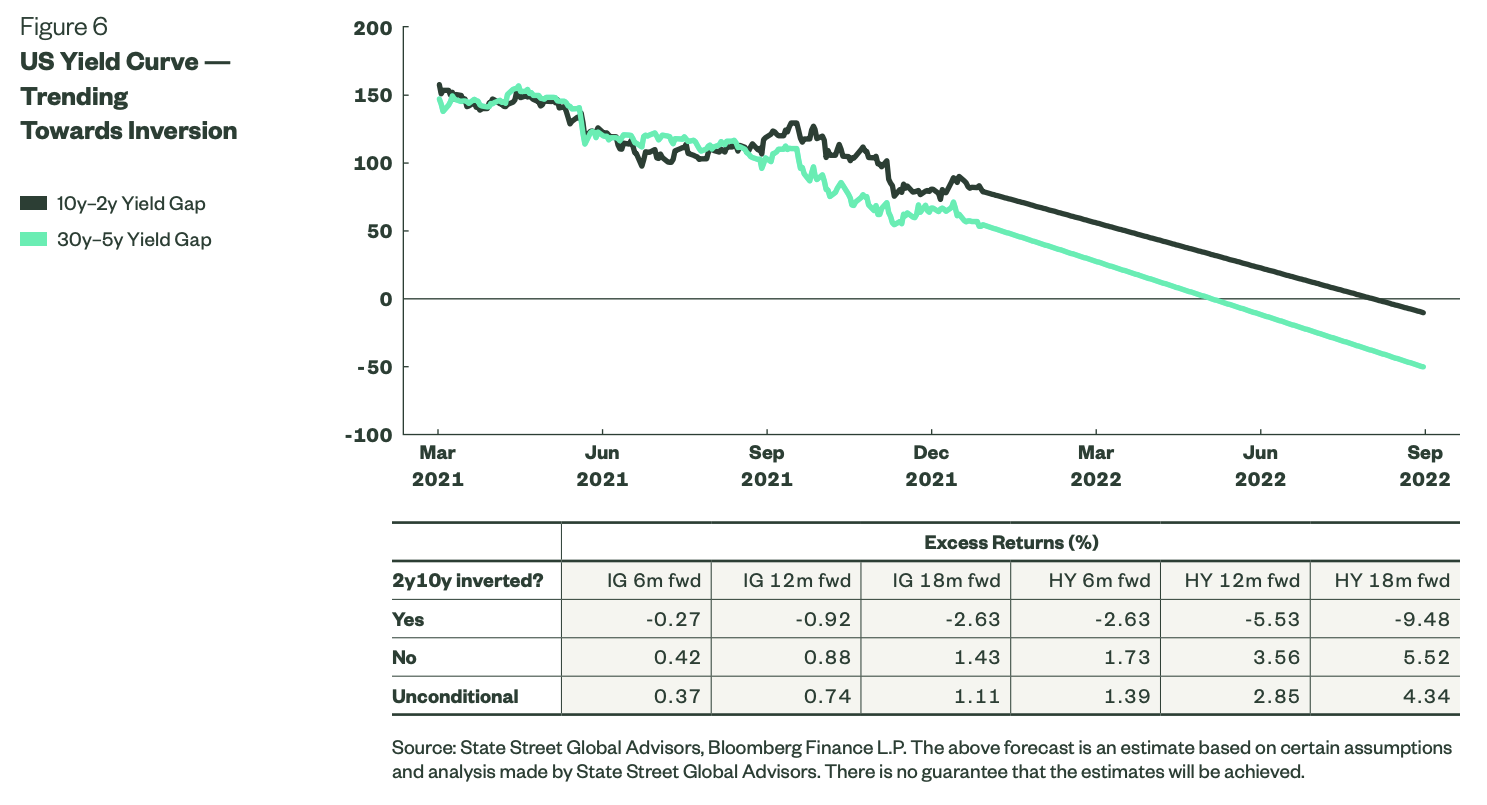

One key indicator to monitor is the US yield curve, which has been flattening since March 2021. If it continues to flatten at this pace, the yield curve could become inverted as early as mid-2022.

This matters not only because an inverted yield curve has typically portended recessions within 18 months, but also because risk assets like equity and credit generally struggle when the yield curve is inverted.

Government bonds tend to perform well in such an environment and, despite low yield levels, would offer protection — although perhaps not as much as investors have experienced in the past. While unlikely to be cause for immediate concern, many investors remain heavily exposed to risk assets and should remain on the lookout for an inverted yield curve in 2022 as another signal of a much shorter economic expansion than we are accustomed to.

Learn more

For further insights from the team at State Street Global Advisors, please visit our website.

Endnotes

(1) Source: CoinMarketCap as of January 7, 2022.

(2) Source: Bloomberg Finance LP as of January 7, 2022.

(3) Source: Reuters “NFT space, where $11 billion in sales took place in Q3 2021” October 4, 2021.

(4) Macy’s Launches First-Ever NFT Series in Celebration of the 95th Annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade® :: Macy’s, Inc. (M) (macysinc.com).

(5) Source: CryptoCompare “Exchange Review June 2021”

July 8, 2021.

(6) Source: CryptoCompare “Exchange Review December 2021” January 8, 2021.

(7) Source: The Block “Trading volume for bitcoin and ether options grew 443% in 2021” December 27, 2021.

(8) Source: US Energy Information Administration, ShortTerm Energy Outlook, January 11, 2022.

1 topic