5 lessons from a decade of growth stock performance

I wrote last month that Forager has been selling some wonderful business over the past few months. That has been controversial for some of our clients. Never sell a great business is a lesson many have taken from the past decade of growth stock outperformance.

I argue that it’s not the right lesson. What has worked is not necessarily what works.

Which doesn’t mean there are not lessons. If holding great businesses forever is the wrong conclusion, hold for longer than you did seems irrefutably obvious given the value of some of these businesses today.

A refresher on business valuation

The value of a share is the present value of all the future cash flows that it is going to pay you into perpetuity. We aim to buy those shares at discounts to fair value and sell them when they reach or exceed it, amplifying the returns that are generated by the underlying business.

With perfect foresight, the logic of this strategy would be irrefutable.

Of course, the future is unknowable and highly variable. In practice, we make the best estimate of what those future cash flows are going to be and put a lot of work into understanding the range and magnitude of the uncertainties. Our estimation is going to be off the mark. The question is which way.

The main lesson of the past 10 years is that getting it wrong on the low side (being too conservative about the future of a business) can be as expensive as getting it wrong on the upside (being too optimistic). When someone says they sold a wonderful business way too early, what they actually mean is that they drastically underestimated its value.

So, with that all as a precursor, here are some of the shortcomings I have gleaned when it comes to erroneously concluding a stock is expensive.

1. Reversion to the mean is a thing. But it doesn’t need to be soon

Jo Horgan, the founder of Australian makeup giant Mecca Brands, was quoted in the Australian Financial Review last week saying: “With same-store sales (growth), we have an absolute goal as a business that we’ll never get below 10 per cent” . I admire Jo’s optimism. And I’d love to own a share in her business (she says there are no plans to list on the stock exchange). In the long term, however, not only are we all dead but everything reverts to the mean. It’s not possible for any business to grow faster than the global economy forever, otherwise, a slice of the pie becomes bigger than the pie itself.

But forever can be a long time away. A common valuation mistake is to assume a good business stops growing rapidly far too soon. My valuation models often assume high growth for the immediately visible future, but a reversion to more subdued growth within the next five to ten years.

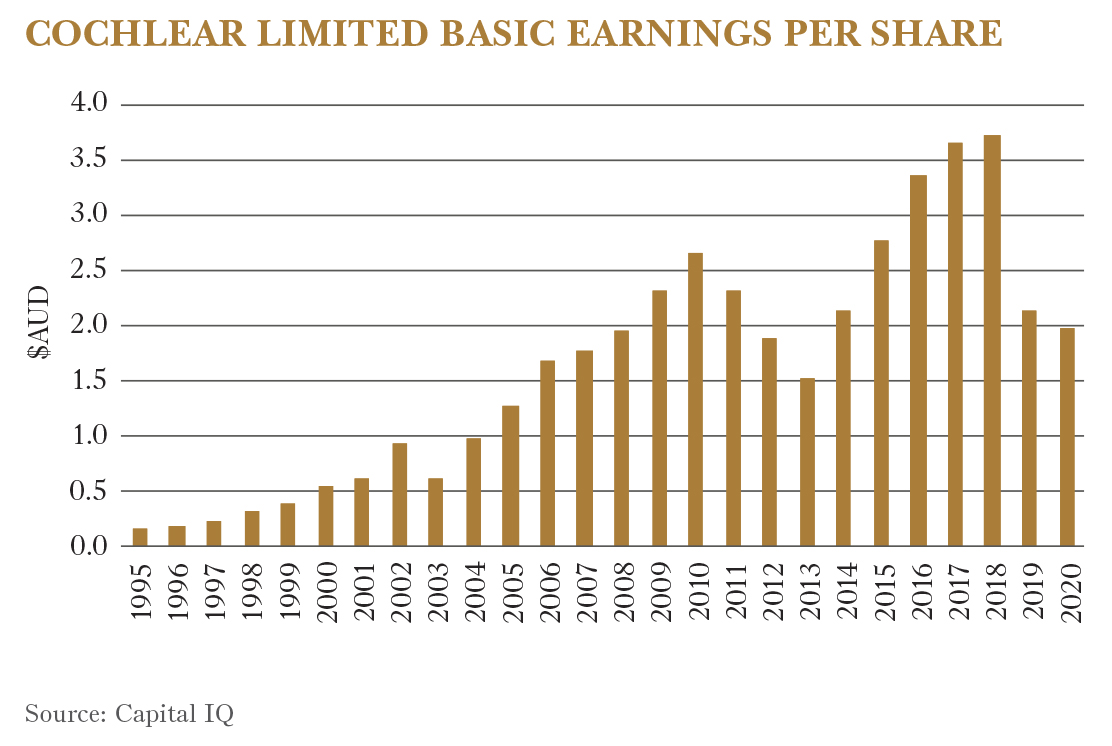

Google and Facebook are recent examples of businesses still growing 20% per annum as they head into their third decades of existence. Australian examples like Cochlear and Resmed have grown at more than 10% per annum for three decades. Sometimes the insight into a stock is not what’s going to happen over the next five years. It’s what is going to happen in the decades after that, when the power of compounding really kicks in.

2. Great products create their own demand

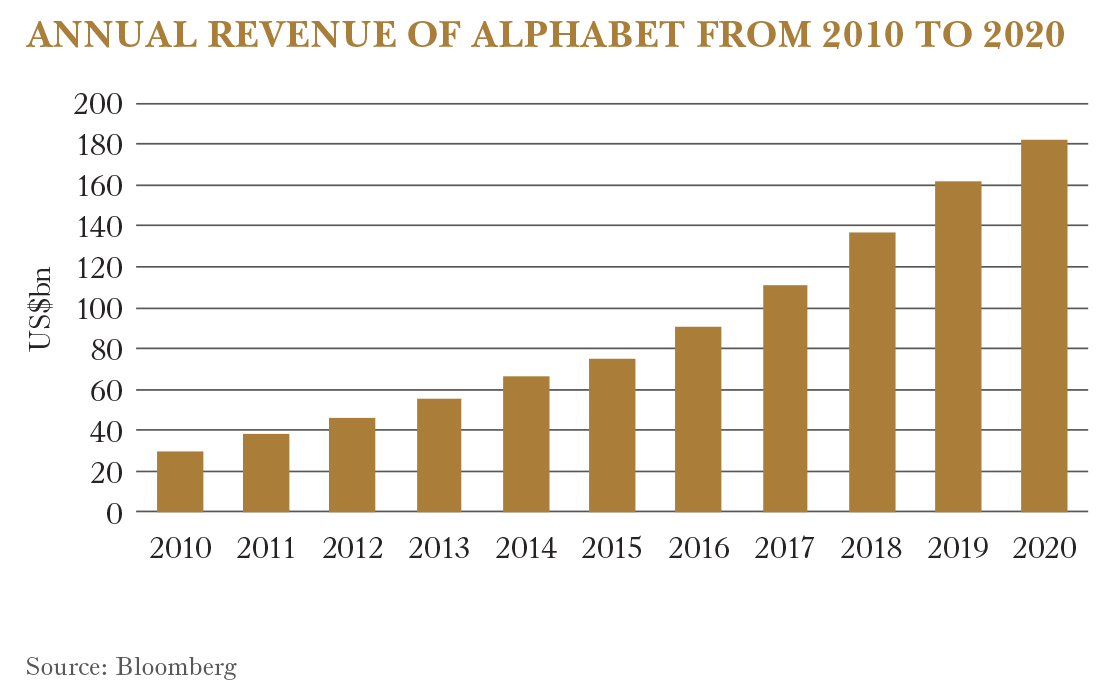

Total addressable market is some jargon you will hear a lot when it comes to growth companies. Rather than making the common mistake of underestimating the growth runway, analysts jump straight to the endpoint. Back in 2010, the Google argument was something like this: Global advertising spend is roughly US$500bn. We expect it to grow 5% per annum over the next 10 years, making for a 2020 addressable market of US$800bn. Online should grow to 30% of the total and I think Google, being the great business it is, can be 30% of the online share. Adding all that up, in 2020 I think Google will be generating US$73bn of revenue.

That wouldn’t have seemed a stupid guess in 2010. Alphabet’s revenue was US$29bn in that year, making it already one of the world’s largest advertising businesses. But it was wrong by a factor of more than two (parent company Alphabet’s 2020 revenue was a whopping $182bn). Analysts weren’t wrong about the shift to online. They just underestimated how much additional demand Google’s products would create from customers that previously weren’t spending a cent. Millions of small businesses that couldn’t afford newspapers or radio now have a way of advertising to potential customers. Google has grown the market and pinched its competitors’ revenue.

The lesson here is not to think of addressable market as something static. It, too, is a variable. And when you find a great company it invariably finds a way to grow demand for much longer than anticipated.

3. The world is smaller than it’s ever been

The concept of winner takes all is nothing new. It is simply economies of scale taken to their logical conclusion. Warren Buffett recognised in the 1960s and ‘70s that most US cities were going to end up with just one newspaper. The newspaper with the most readers generates the most advertising revenue which allows it to spend the most on creating content that attracts the most readers. Supermarkets (size makes for lower prices) and stock exchanges (liquidity) have long shown the same characteristics.

The difference in the 2020s is that the winners can be global. Melbourne had one great newspaper business, and so did every meaningful city in the world. Now there’s Google, which dominates the Western world. Netflix is not just killing Australia’s Nine, it’s killing every free to air and cable channel in the world.

This is worth keeping in mind when contemplating the value of your business. Harrods and Selfridges were wonderful London-centric businesses. What if Farfetch is the Harrods of the world?

4. Standard heuristics are flawed when valuing rapidly growing companies

All of this plays into the most common mistake. “Rocket to the Moon trades at 40x earnings, therefore it is expensive”. It’s a lazy conclusion (I’ve been guilty). And it can be very wrong.

Twenty years ago someone (me?) looking at Cochlear could have reached that exact conclusion. It was trading on a price to earnings ratio of more than 30.

With the benefit of hindsight, you could have paid 150 times earnings and have still generated a 10% annual return (including dividends). All of these heuristics, or rules of thumb, have assumptions behind them that need to be probed. Under what scenario is 40 times earnings expensive? What would it take for 40 times earnings to be cheap?

Conventional measures lose relevance in the context of long-term compounding math. When a company compounds earnings exponentially (15% per annum for the last 20 years in the case of Cochlear), the fair value can be a seemingly absurdly high multiple of early-year earnings.

5. Conservatism still the name of the game

Having said all of that, I’d still argue the wider trend at the moment is towards dramatic overvaluation of potential growth. The logic used above is being applied to a lot of businesses that don’t deserve it. Very few of today’s optimistically priced growth stocks will become the next Google or Cochlear. And, because so much of the anticipated value depends on what happens in 10 and 20 years’ time, the consequences of overestimating long-term growth rates can be dramatic.

We need to be wary of selling just because a share price has risen. We need to put as much work into the decision to sell a great business as we did the decision to buy it.

But growth is just another variable. We’re going to apply the same margin of safety we apply to all the other variables. And we’re not going to let the exposure to any one business become an irresponsibly large part of either Forager portfolio.

As Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote in To a Mouse, “In proving foresight may be vain: The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men, gang aft agley.” Often go awry they do.

Access a unique portfolio of global shares

If you share our passion for unloved bargains and have a long-term focus, Forager could be the right investment for you. Click 'CONTACT' below to get in touch with us.

1 topic

2 stocks mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)