60/40 is wounded

They say justice is slow as well as blind: ‘Justice limps along but gets there in the end’ - Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Trends in financial markets can be like that, taking decades to arrive at the significant moment but demanding attention when they do. It has taken 40 years, but investors solving for a mix of income and safety are facing a reckoning because the default combination of bonds and equities (the 60/40 portfolio) is now not up to the job.

There are three main reasons for this:

Firstly, income from most sources is under pressure. Government bond yields in major developed markets are close to or below zero, share dividends have fallen, and cash rates are low.

Secondly, even assuming the status quo persists, an investor can no longer rely on bond prices to rise at times of economic distress.

Thirdly, for the first time in decades inflation is a credible threat.

40 years of falling bond yields means 40 years of falling income

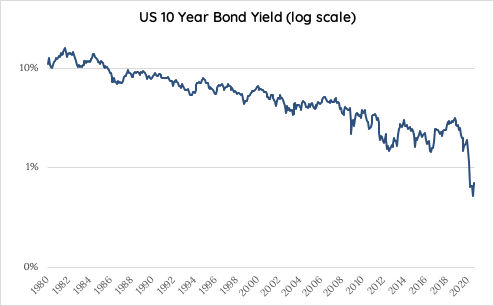

Yields on developed market government bonds have been sinking since the early 1980s. Taking the US 10 Year Benchmark Government Bond as an example, for most of the time the decline in absolute terms was gradual. However, the chart below shows that the pandemic driven dive at the start of this year to 0.7% has been sudden and breathtaking.

Source: Bloomberg

The consequences for savers are considerable and talking about the yield on ten-year bonds can obscure the hard reality: yield is income to savers. When we write about forty years of falling yields, we are also writing about forty years of falling income.

High prices, low growth

There are also the implications of high bond prices to contend with.

Firstly, yields to maturity (income plus capital gain or loss as an annual percentage) can be calculated with certainty. And the certainty in some developed markets is that if you buy a bond today and hold it to the end of its term you will lose money in absolute terms. Secondly, an investor can no longer rely on the price of a bond to rise in times of economic distress, to help mitigate the likely losses equities deliver in a downturn.

With bonds now offering very low yields and interest rates close to zero fixed income is unlikely to behave as it has in the past. This is not theoretical. At the start of this year Australian short rates were just 75bps, which investors knew left the Reserve Bank of Australia limited scope to cut rates, capping the upside in bonds. Thus, when pandemic driven panic was driving down equity markets in February and March, the best you can say of the Australian 10-year bond is that it did not lose money, but unlike previous periods of equity market declines this sort of bond was not making money for the investor as she was losing money in equities.

COVID-19 and the downside risk to bonds

Even if the status quo does no more than persist, the outlook for investors in developed market bonds is unattractive and the consequences for portfolios are significant. However, there is a threat to the status quo that makes inflation a credible risk for the first time in decades.

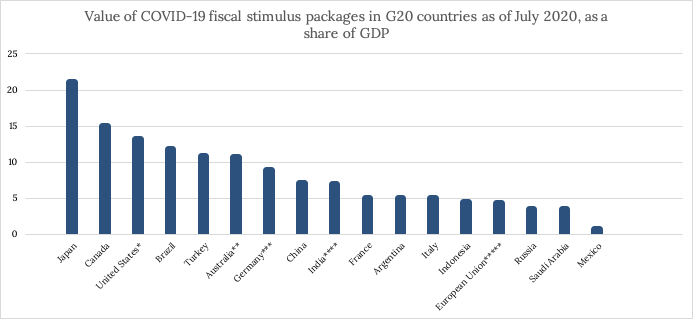

Today we are seeing the largest level of non-wartime fiscal stimulus, nearly ten times as large as in the GFC. Including loan guarantees, the G20 group of nations has provided fiscal stimulus to the end of June equivalent to 13.6% of GDP compared to 1.4% of GDP in March of 2009. Many of these measures have taken the form of direct transfer payments and credit guarantees. These actions are quite different to monetary policy measures and have the power to affect credit creation directly and the velocity of money, in a manner that monetary policy alone does not.

Source: Statista

Central banks, already cutting rates and embarking on large-scale asset purchases, are signalling their tolerance for higher inflation should it materialise. Late in August, the US Federal Reserve Chairman announced a new framework for monetary policy, targeting full employment as a priority and shifting the inflation target from 2% to an ‘average’ of 2%. He also abandoned a ‘balanced’ approach to policy; meaning the Fed will no longer pre-emptively raise interest rates but rather let inflation versus target run high.

Whether or not such measures in the US and other countries succeed in combatting the economic effects of the virus, they raise at least the possibility of inflation. This is not something reflected in bond prices and makes them vulnerable to capital losses in real terms if held to maturity or absolute losses if sold as inflation moves higher. For the first time in thirty years, bonds and equities could fall together with both sides of the 60/40 portfolio losing money.

60% equity and 40% fixed income has been the mainstay of portfolio construction for savers over the past 40 years. Today, as the bond component provides little income and limited capacity to appreciate at times of equity market declines, fixed income has lost much of its appeal. This gives savers the uncomfortable prospect of having to take on more equity market exposure at a time of high valuations in an attempt to generate adequate, stable, consistent income while limiting losses.

We think portfolios today need to reflect the challenges of the current investment landscape. Doing nothing means living with less certainty and lower income - not an outcome anyone should be happy to accept.

Like this wire? Let us know by hitting the 'like' button to the left.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

4 topics