A bold look at sovereign default risks

.png)

When assessing sovereign default risks, most portfolio managers tend to adopt a naive and mechanistic approach, often leading to misleading or inconsistent results. During my tenure at a sovereign wealth fund in Oman, I often met foreign analysts and frontier market fund managers who consistently sought my forecast for the Sultanate's public debt-to-GDP ratio.

My response, reminiscent of Rhett Butler's iconic closing line in Gone With the Wind , invariably surprised them: “I don't know, and frankly, I don't give a damn.”

To understand my stance, we must revisit the fundamentals: Why do we measure government debt relative to GDP? Essentially, GDP gauges a government's fiscal capacity. Historically, initial calculations of national income aimed to assess a state's (or monarch's) ability to support war efforts by extracting resources from its citizens (or subjects).

However, in Oman's case, the bulk of government revenues stem from oil exports, not from personal income or sales taxes, as these are non-existent. Consequently, a more meaningful and relevant indicator for assessing the sustainability of Omani government debt is its ratio to oil revenues. Essentially, those holding Omani government bonds are betting on an oil price rebound, and to a lesser extent, on real GDP growth (which, nevertheless, is significantly influenced by oil prices).

Clearly, Oman and other nations with substantial hydrocarbon reserves or natural resources are exceptions in fiscal policy matters. Yet, even when examining advanced, diversified economies that rely on taxation for revenue, comparing debt-to-GDP ratios can be misleading.

Imagine two hypothetical countries with identical debt-to-GDP ratios, debt service, primary deficits, economic growth rates, and currency. It might be tempting to assume they face similar default risks. This is not necessarily true.

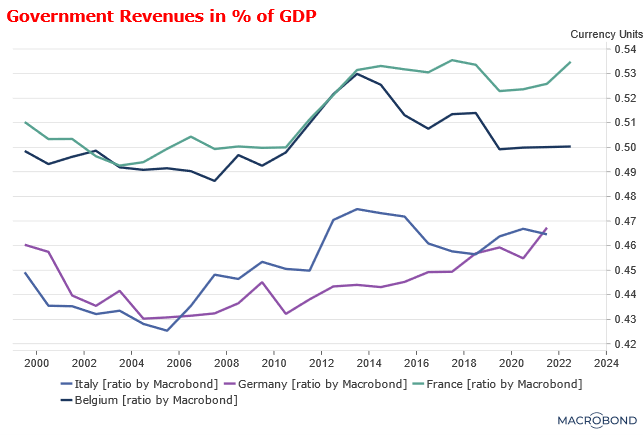

If one country's government revenue-to-GDP ratio is significantly higher (say, 52% versus 42% - see graph below), it indicates more room for tax increases without excessively damaging the economy. Conversely, the country with a higher ratio has limited scope to raise taxes without crippling the private sector.

A frequently overlooked aspect is the unreported pension system's future liabilities, often multiple times the GDP. This 'elephant in the room' poses a massive social and political challenge, potentially devastating government budgets in the near future, yet is often ignored by governments.

Moreover, official GDP figures include the so-called gray economy, comprising both legal and illegal activities that largely avoid taxation. Hence, a country with a larger informal economy relative to its GDP is in a more precarious fiscal position due to its smaller, more volatile tax base.

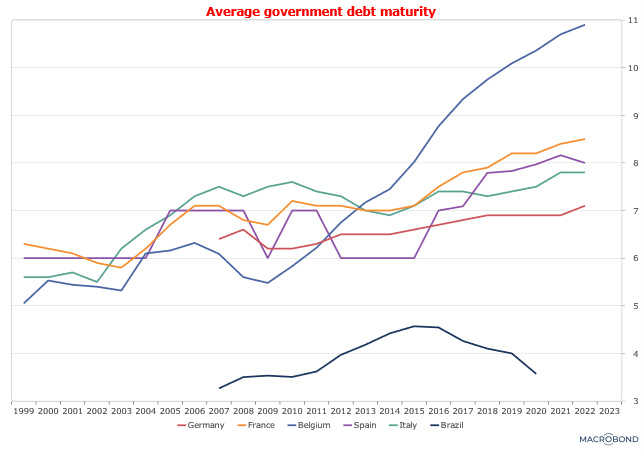

Other significant differences often overlooked in simplistic analyzes include the average maturity of government debt (see graph below), foreign currency exposure, domestic savings rate, and bond market liquidity.

Even the expenditure side can reveal surprises. For instance, the IMF estimates that when considering off-balance sheet debts of local governments, state enterprises, and quasi-fiscal entities in China,* the total public debt to GDP ratio is projected to reach 143.4% in 2026 and 164.1% in 2030 This is despite China's social services – such as healthcare, pensions, and education – lagging significantly behind those of developed countries. In essence, any government spending cuts would be politically challenging.

Certainly, governments may possess substantial assets, such as buildings, infrastructure, or public enterprises, which could theoretically be sold or privatized. But this requires political will to compare entrenched interests. Additionally, selling loss-making enterprises or non-profit infrastructure (like the proverbial 'bridges to nowhere') rarely yields substantial proceeds.

In conclusion, a thorough assessment of government fiscal data from both macroeconomic and political standpoints is crucial, a task that cannot be accomplished by merely glancing at headline figures.

(*) W. Raphael Lam and Marialuz Moreno-Badia “Fiscal Policy and the Government Balance Sheet in China” IMF Working Paper WP/23/154 August 2023, Washington, DC.

2 topics

.png)

Macrobond delivers the world’s most extensive macroeconomic & financial data alongside the tools and technologies to quickly analyse, visualise and share insights – from a single integrated platform. Our application is a single source of truth for...

Expertise

.png)

Macrobond delivers the world’s most extensive macroeconomic & financial data alongside the tools and technologies to quickly analyse, visualise and share insights – from a single integrated platform. Our application is a single source of truth for...

.png)