A Budget funded by "unconventional" means

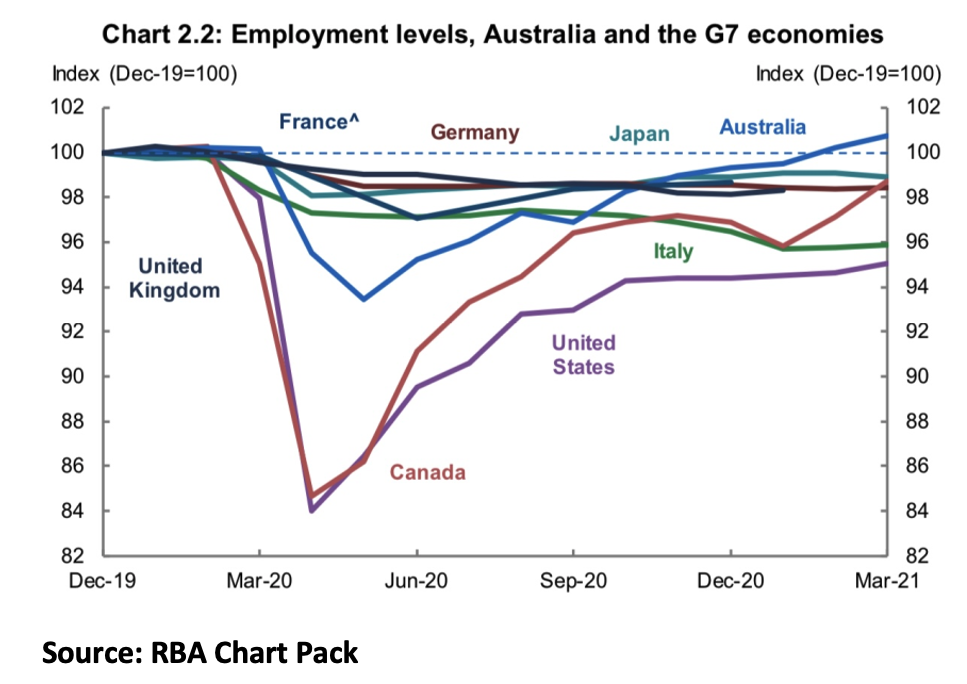

When Treasurer Josh Frydenberg unveiled his “Securing Australia’s Recovery” budget, he delivered his address to Parliament without uttering the words “quantitative easing”. But deep in the Budget’s supporting papers, there was an acknowledgement that its framing was supported by “unprecedented unconventional monetary policies” adopted by the Reserve Bank of Australia.

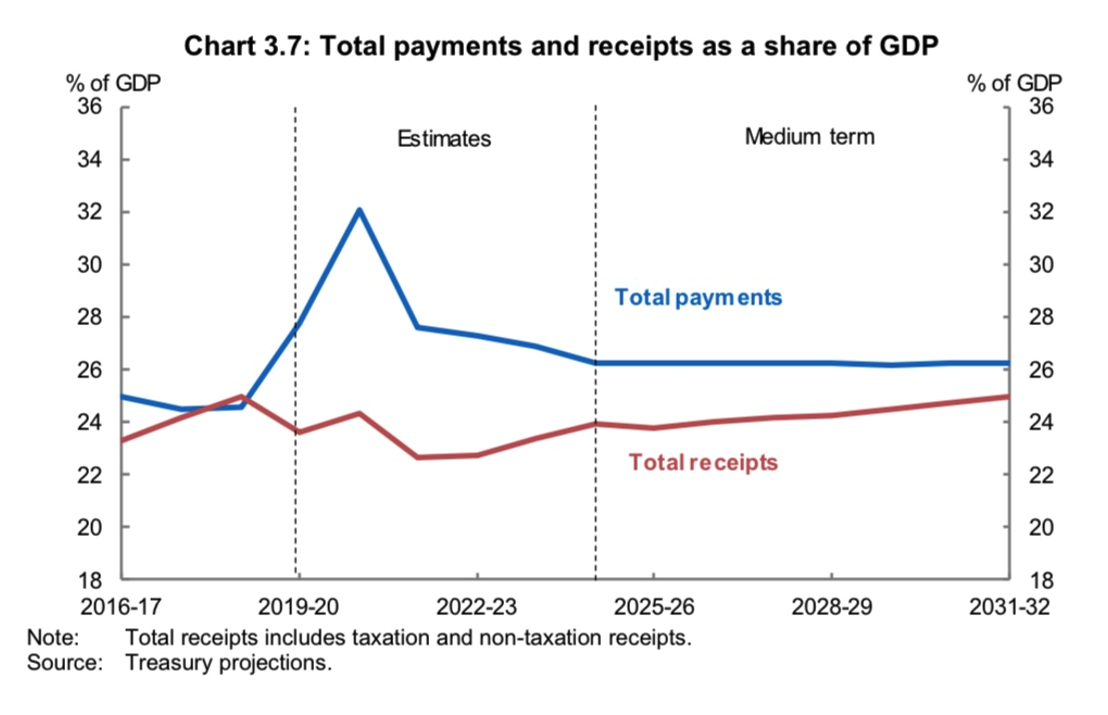

Source: Treasury, Budget papers

Following on from the massive deficit of FY21 ($160 billion), vast fiscal spending is to continue into FY 22 and beyond. Therefore it is clear that this government has turned its back on the conservative economic dogma that had directed it to balance the totality of budgets through an economic cycle.

The government (and seemingly its Treasury advisors) now fully embraces the new Modern Monetary Theory practices that have captured most developed world thinking. Whilst at this point, we do not dispute that this policy setting is appropriate, we do question the continued failure by both government and Treasury to acknowledge that it exists. In passing and on this point we do note that the Opposition is numb on its acknowledgement of QE as well.

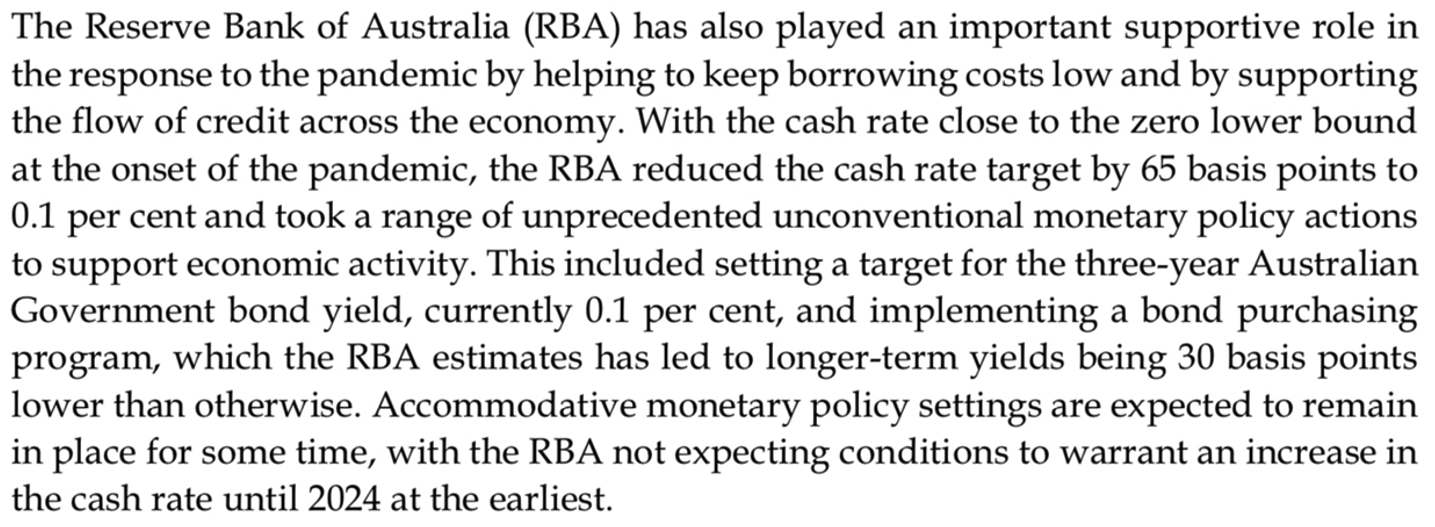

The projected FY21 and FY22 budget outcome flows from a stronger than expected economic rebound supported by massive stimulation and funded by the issuance of bond debt consumed and/or controlled by the RBA aggressive use of QE. At its core, the strong economic outcome is also due to the effective suppression of the Covid-19 pandemic. The recovery and forecast growth is captured in our first chart.

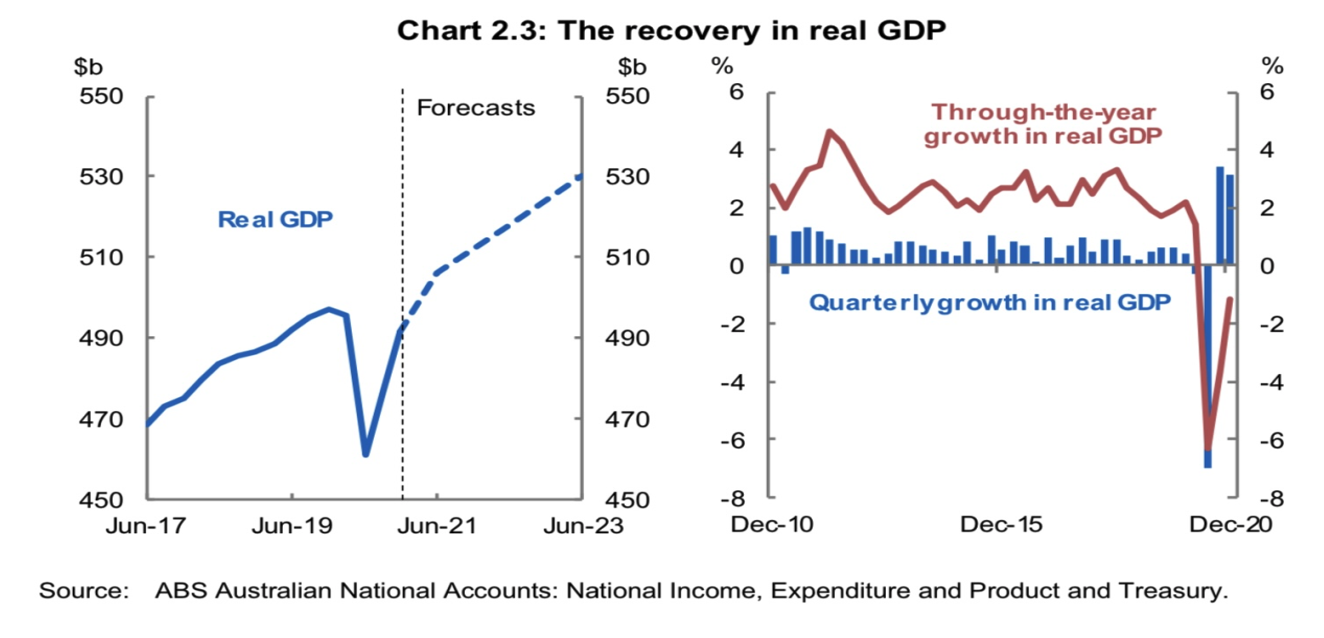

Importantly, the rapid economic recovery has reduced the unemployment rate to 5.6% and has taken employment levels beyond that recorded pre-pandemic. This employment growth supports the budgets economic growth forecast of 4.25% in FY22.

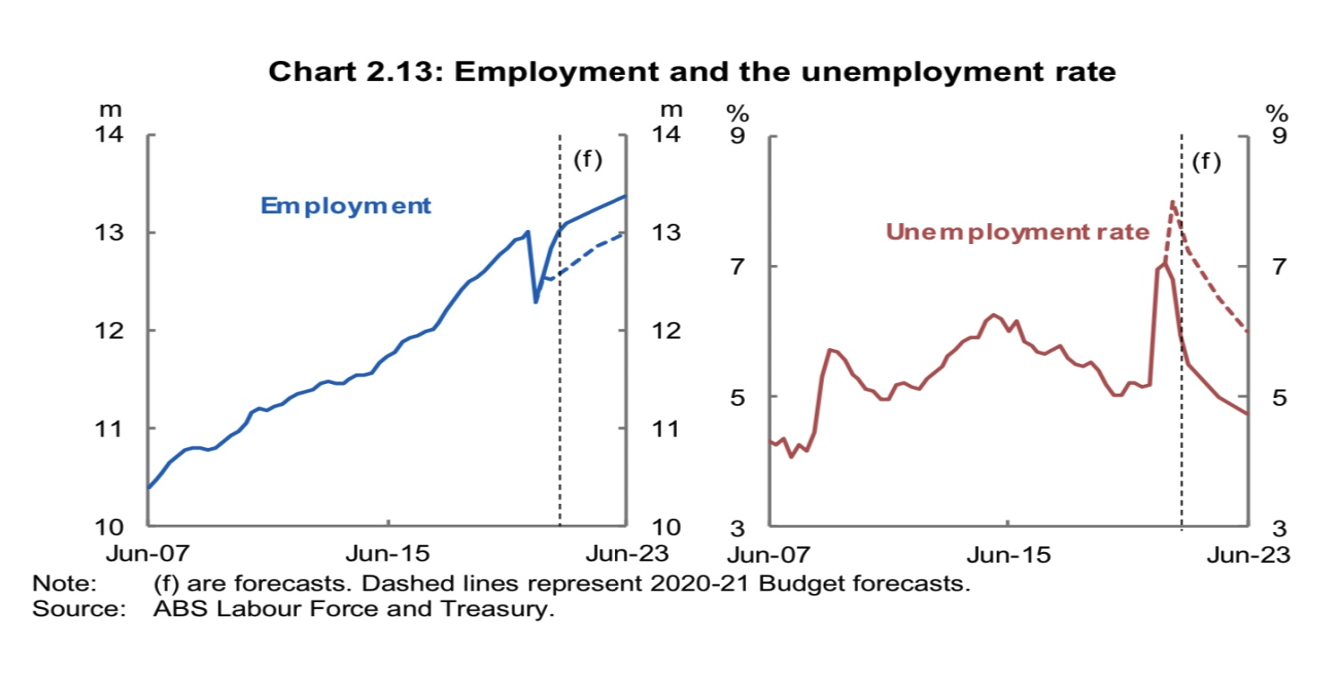

Australia’s recovery and now its growth in employment levels is impressive when compared to our developed-world peers.

Further out, and after a bumper growth year in FY22, the outlook ( according to the budget) is more subdued. Until borders fully reopen, international travel recommences, education services are available (to international students) and immigration fully recovers, Australia’s economic expansion will be constrained, and growth is projected by the Government at just 2.5%.

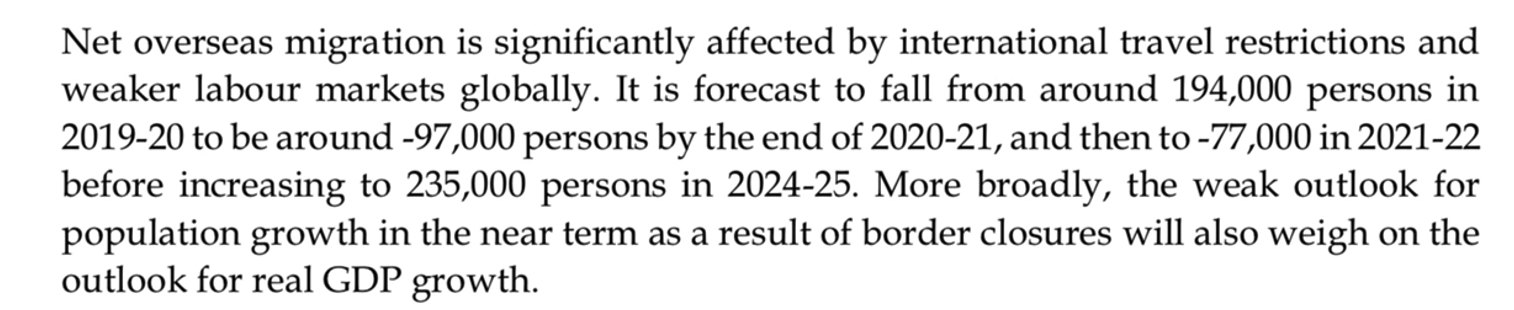

Specifically with regard to immigration the

budget papers disclosed:

Source: Treasury, Budget papers

Given the headwinds created by closed borders, the growth is arguably satisfactory even if it is clearly supported by fiscal stimulation which will remain elevated in FY22.

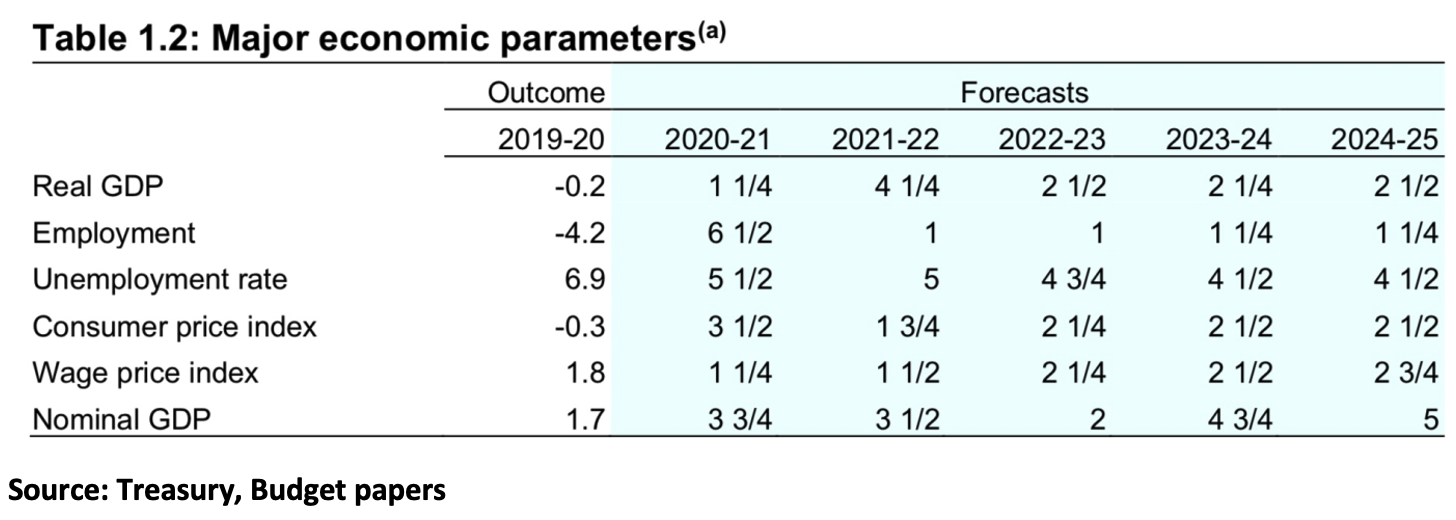

The major economic forecasts are contained in the following table which can be highlighted as:

- Subdued growth from FY23 onwards,

- Steady improvement in employment,

- A moderate uptick in inflation,

- Wage’s growth that eventually tracks inflation.

The Budget agenda

The Morrison government has proposed a pre-election spending spree worth tens of billions of dollars, with tax cuts and boosts for age care, childcare, and women’s wellbeing - partly funded by a A$53bn windfall from surging iron ore prices and the better than expected jobs recovery. Indeed, the spending spree flows into FY23 and gives the government plenty of options as to when to call the next election. It provides the choice of a late 2021 election, or a mid-2022 election - but any decision on dates will probably depend on the success of the vaccine rollout, and how the government is travelling in the polls.

Outside the political agenda and given the

remarkable recovery that is underway in the Australian economy – it is back to

pre-Covid levels of output – it was a little surprising that the forecast

deficit for FY22 was still to be 5% of GDP (net operating cash deficit of $106

billion).

Clearly, the economic stimulation of the budget is a positive for the macro outlook and therefore risk/growth assets such as equities and property. However, it does invite the question about how long the RBA will keep its ultra-accommodative “unprecedented and unconventional” settings in place. To date, we have been reassured that rates are virtually fixed at ultra-low levels until 2024, but pivots by central banks as and when conditions change have been known to happen in the past.

In looking out we should remember that the budget is by nature a conservative document, and Treasury’s macro growth assumptions (past FY22) may end up being too conservative. Unemployment could fall faster than expected, and iron ore could again positively surprise.

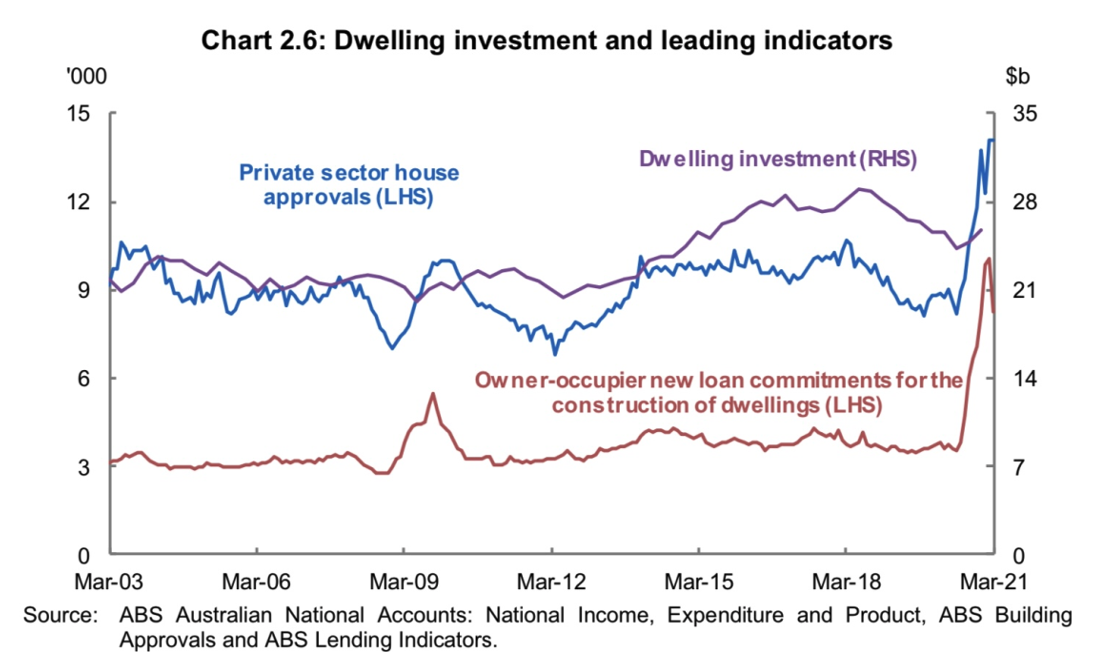

Further, in terms of direct stimulation in FY22, we observe that some of the existing personal income and business tax incentives were extended. Notably, infrastructure was added to, there was also a big boost to care services, while other measures will further support housing demand.

Therefore, we expect companies leveraged to

domestic demand should do relatively well in this environment (e.g.,

construction, housing, retail services, logistics, financials, autos, and the

labour market).

The government also unveiled several big-spending pledges, including a $17.7 billion package aimed at improving age care, $1.7 billion investment in childcare and $1.1 billion to boost women’s safety, health, and economic security. It also includes almost $30bn in personal income and temporary business tax cuts.

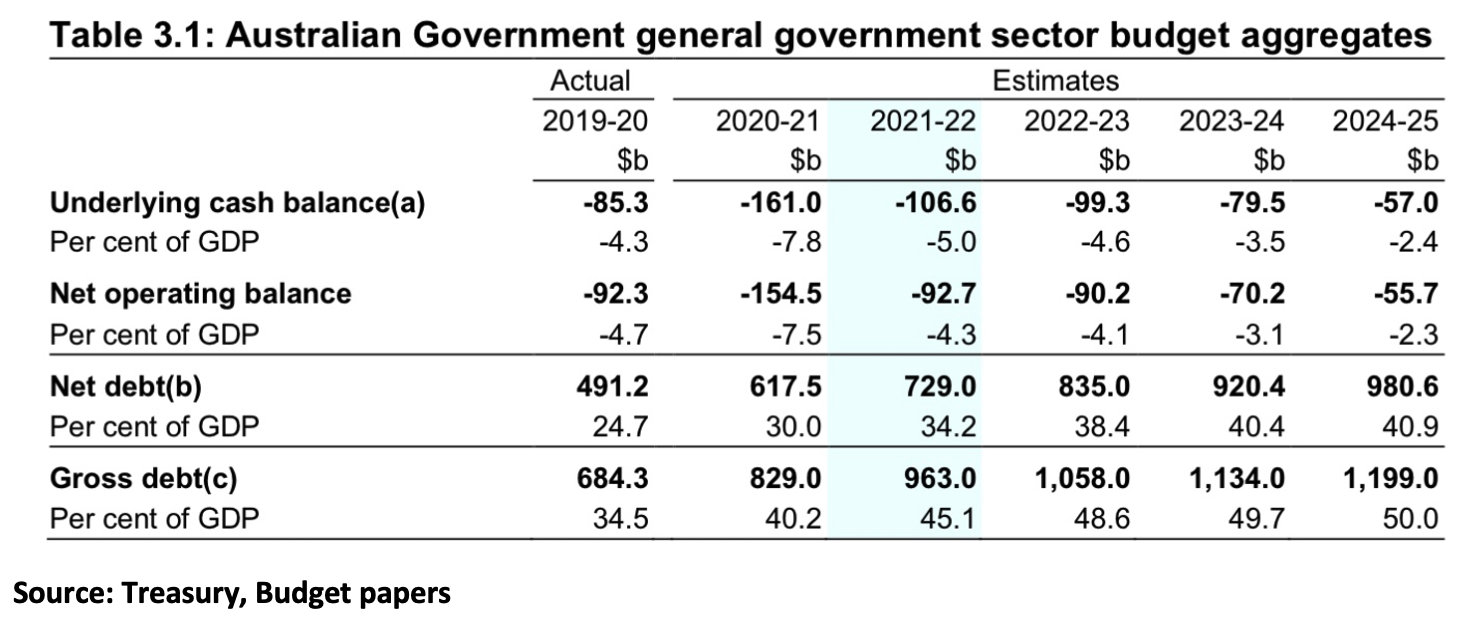

The budget papers show Australia’s deficit is forecast to reach $161 billion this year (2020-21) or 7.8% of GDP. This is $52.7 billion lower than the forecast six months ago, although it remains at a modern-era high. Tax receipts are forecast to be $35 billion higher than anticipated in October due to the increase in employment, consumption and a boom in company taxes linked to record iron ore prices.

The government had anticipated iron ore prices would be $55 per tonne in its previous economic forecasts. This week the price of the steel-making ingredient hovered close to $230 per tonne. The jobs recovery has also reduced the forecast spend on welfare. By 2024-25 the government forecasts the deficit will be $57 billion or 2.4% of GDP.

As the graph below shows, the government is not projecting either a surplus or a balanced budget before the end of this decade.

The budget comments, tables, and charts

As has often been the case in past budgets, it is the background documents provided by Treasury that provides important insights in understanding the budget and the focus of macro policy settings.

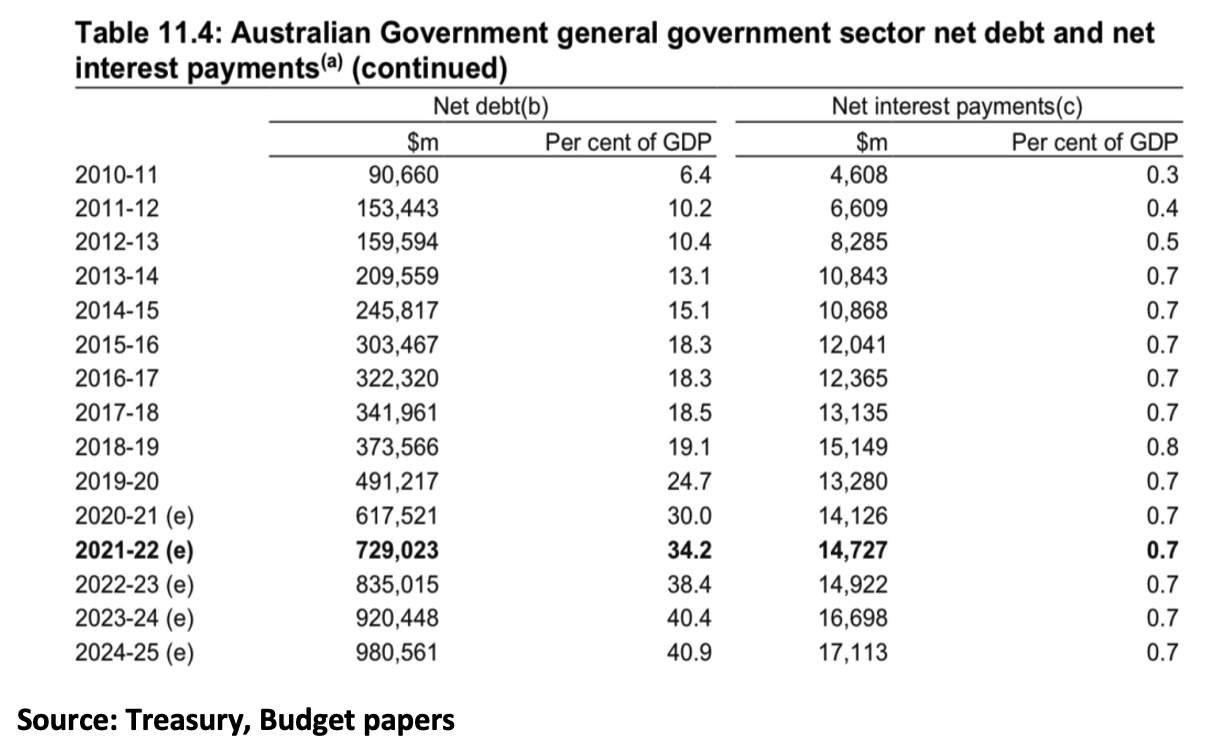

There is now much media discussion over the growing level of government debt. The growing concerns by commentators are being challenged by the Treasurer who claims that Australia can outgrow its debt by using managed deficits.

While this argument is reasonable and has been suggested by Clime for many years, it understates the significant support provided by strategic initiatives that are being adopted by both Treasury and the RBA.

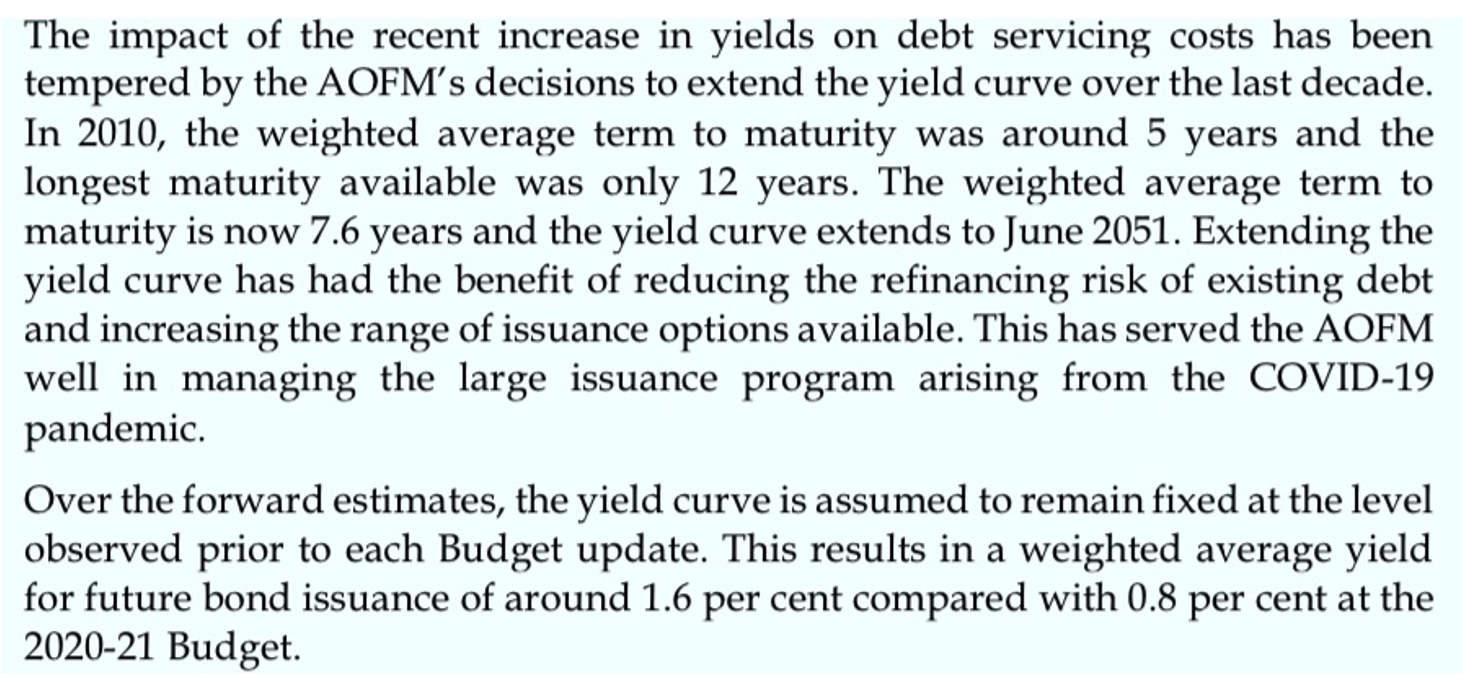

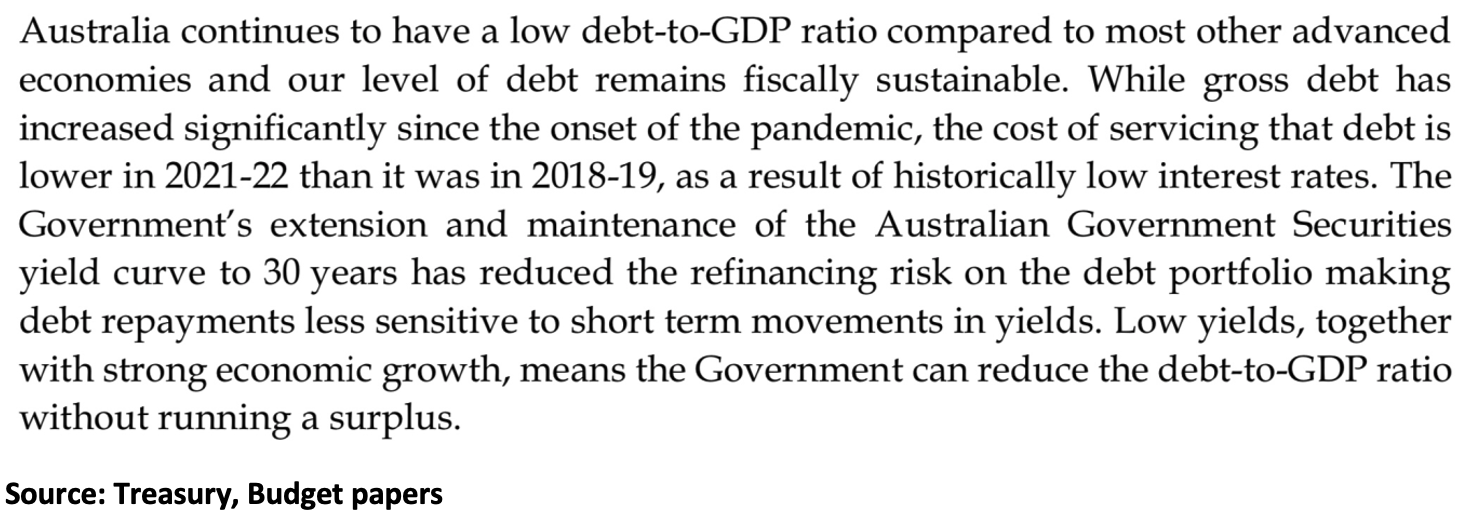

For instance, the following extract from the budget papers explains that the Australian Office of Financial Management (part of Treasury) has extended the average maturity of Australia’s bond issuance.

Simply stated (and hidden in the verbiage below),

Treasury is issuing more longer-dated bonds at near historically low interest

rates. Indeed, many of the recent issuances (although at slightly higher yields

than during the pandemic) are being set at yields below current and projected

inflation. That implies negative real yields.

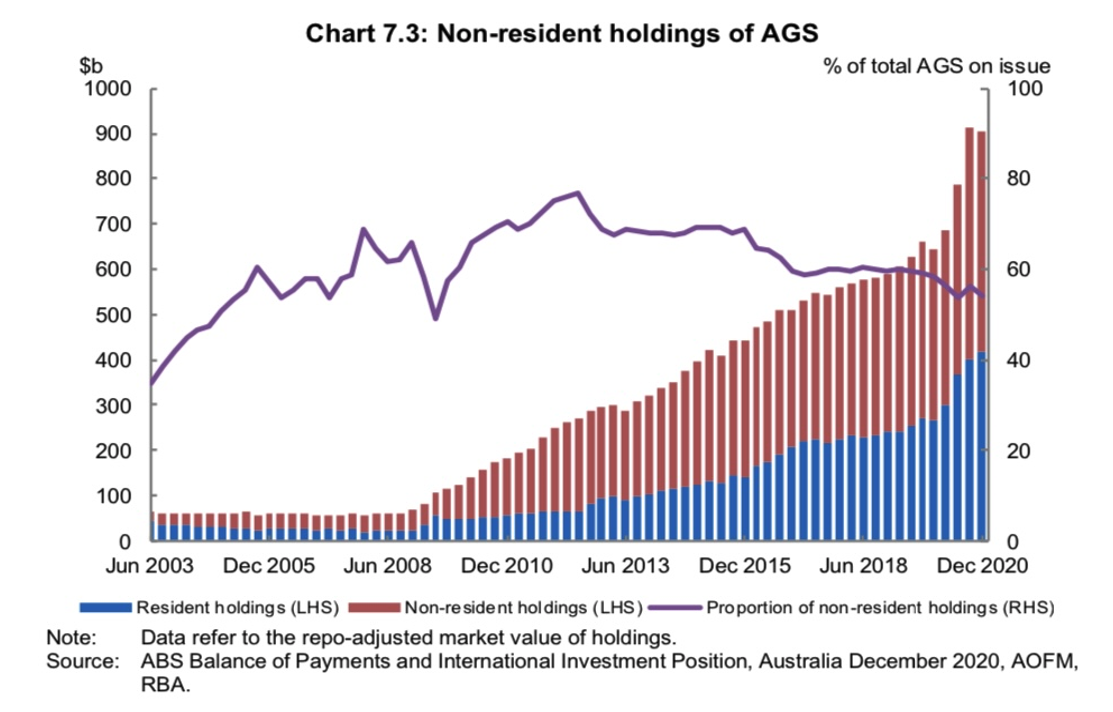

The increased issuance of bonds is captured in the table below which also shows a disturbing and annoying (to the RBA at least) feature of the ownership of Australian bonds. As of December 2020, foreigners still owned more government bonds than Australian entities.

It is hoped that following the massive QE programs adopted by the RBA and those that will be undertaken through 2021 and beyond, foreign ownership of our bonds decreases.

This is important because, in a crisis, it is foreign creditors that pose the most risk to the financial system of an economy. In a panic, they will sell out of bonds and therefore push up yields.

It is also a feature (noted across the developed world) that central banks are buying more of their government-issued debt (through QE) and crowding out foreign owners of their bonds. In Australia, it is notable that the RBA is currently buying more bonds in the secondary market than Treasury is issuing in the primary market.

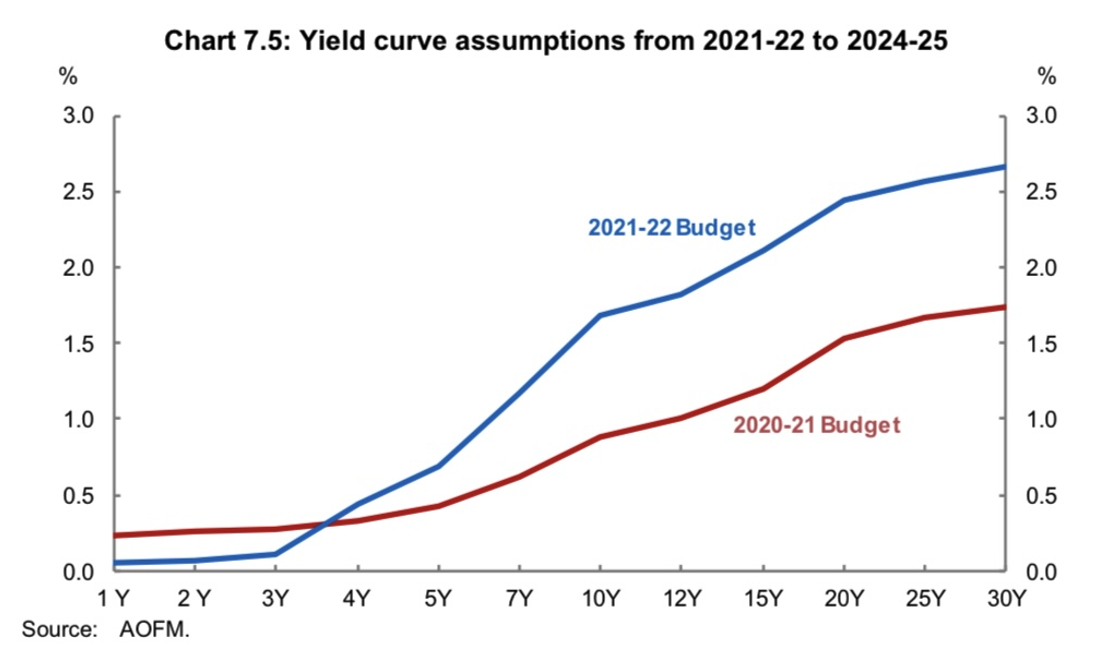

Therefore management of bond yields through forward guidance and aggressive bond purchasing is clearly being undertaken by the RBA. The following chart is noteworthy because it shows that whilst over the last six months longer-dated bond yields (past 4 years) have risen modestly, short-dated yields (shorter than three years) have fallen.

While 10-year to 30-year Australian bond yields have risen since last October, they are hardly of concern. The Australian Treasury will be actively targeting long-dated issues to secure low rates of interest and bring down the cost of our burgeoning debt.

The next table shows that while

net Commonwealth debt will grow from the current $600 billion to near $1

trillion in 2024, the net interest bill will barely rise – from $14.7 billion

to $17.1 billion. Therefore, the burden on the budget is muted.

The forecast growth in net debt to about $1 trillion in 2025 does not faze the government and it draws upon international comparisons to justify its position. It also notes the benefits of lower interest rates and costs – but without specifically acknowledging how it is achieved.

Another important table is extracted below. It shows the series of Australian bonds currently on issue and their redemption dates. It also gives a great insight into the legacy of past bond issuance and the benefits that will flow to the budget when bonds are rolled over.

For instance, and right now, some $25.8 billion of Australian bonds that are costing 5.75% to service will be rolled over into a new series of bonds that will probably cost 4% per annum less to service. This amounts to an interest saving of $1 billion per annum.

Over the next two years, some $130 billion of

bonds will mature and be rolled over. With aggressive QE policy being

undertaken the government budget will save about $4 billion in interest per

annum on these new issues.

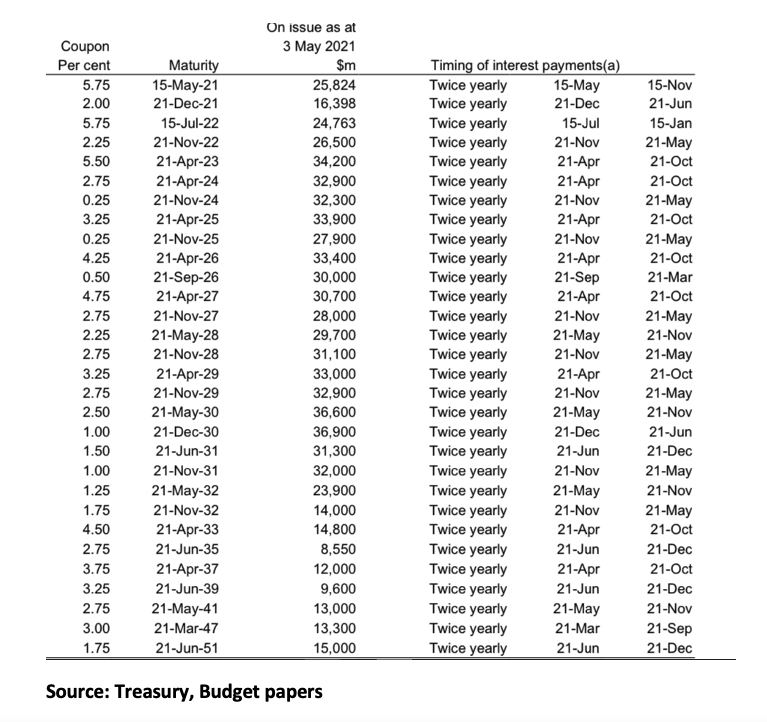

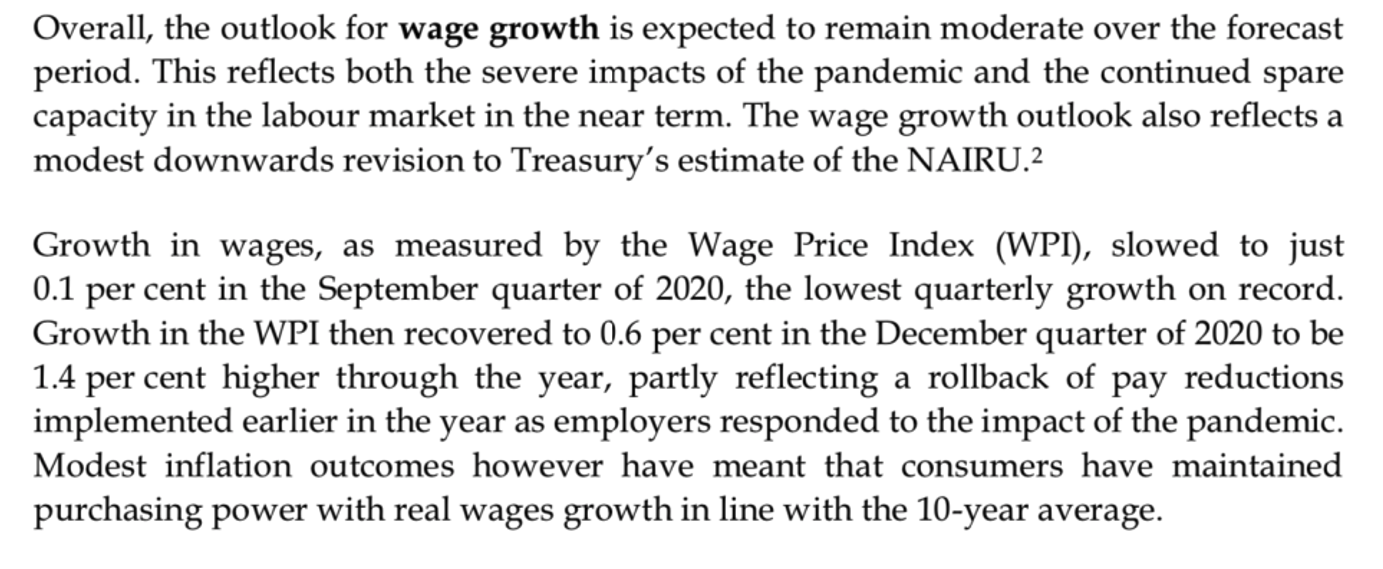

Away from the “unconventional” funding of the budget, we end this budget review by noting the charts below that focus on business investment and consumer spending.

As noted earlier, there is significant taxation support in the FY21 and FY22 budgets for business investment. Outside the booming resources sector, there continues to be a significant imperative to stimulate non-mining investment in an economic environment held back by border closures.

The instant tax write-off for capital investment for small and midsized companies has buoyed the outlook for capital investment. It will also be a boon for retailers like Harvey Norman (ASX: HVN), JB Hi-Fi (ASX: JBH) and Bunnings.

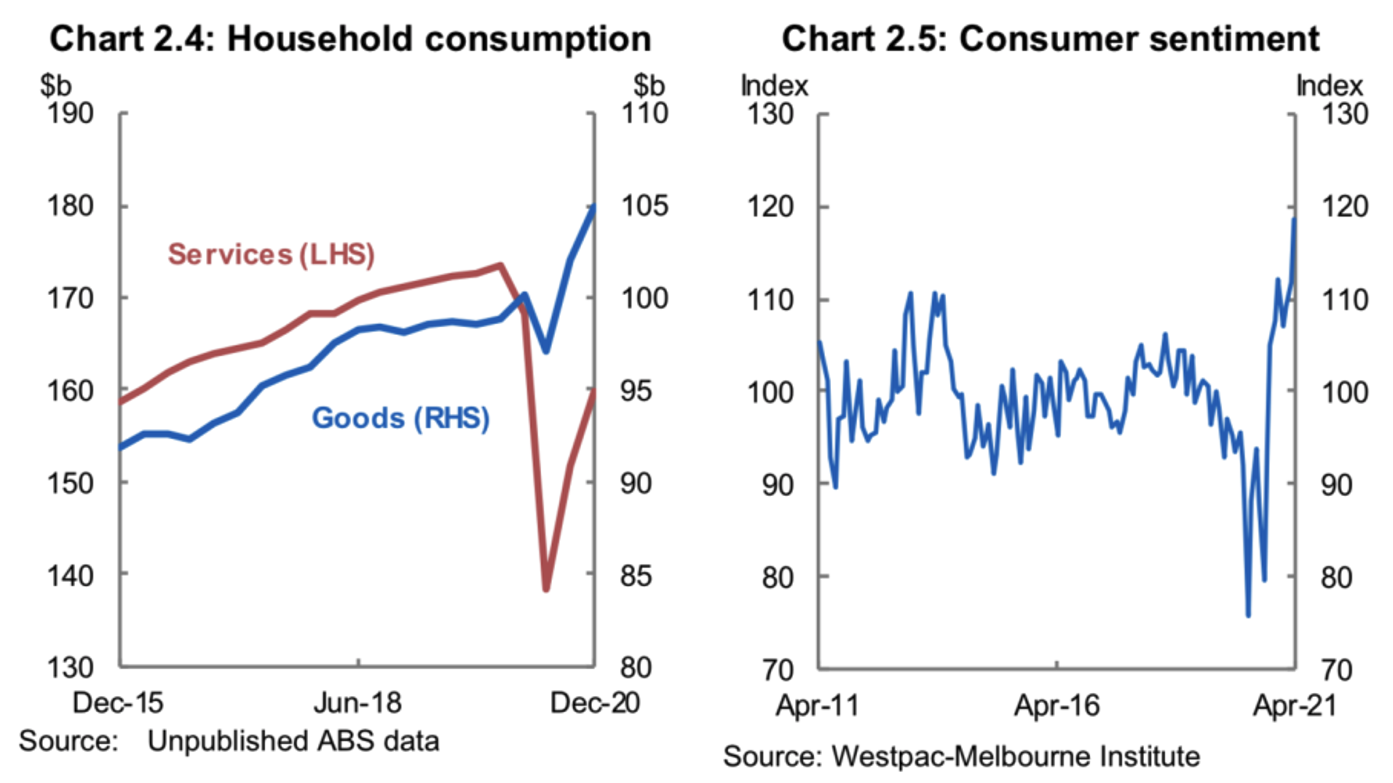

The moderate outlook for wages growth was noted in the budget papers and this resulted in the (much needed) extension of taxation benefits to low-income earners.

Source: Treasury, Budget papers

The above statement outlines an unsavoury truth about wages in Australia. Since the GFC it is clear that average Australian workers have not benefited from real wages growth and therefore tax relief is needed. Further, the wages of essential workers to aged care, childcare and healthcare remain too low for an advanced society. More so given that residential prices continue to gallop upwards and make housing affordability a severe problem for average workers.

Despite the above, our final chart is supportive of growing household consumption over the coming years. As we have described, the Australian economy has bounced back strongly with a robust recovery in employment. On the back of this, the consumption of goods has offset the decline in the demand for services. Therefore, we anticipate that when borders are reopened there will be a surge in the demand for services and this will underpin further sustained growth in the Australian economy.

The Australian economy is set on a solid growth trajectory. The recovery has been rapid and surprised both the Government and Treasury. But the next leg of growth remains challenged by COVID-19 waves across the world which will delay the reopening of borders. This has allowed the Government to justify a sustained deficit (5% of GDP) and maintain stimulation to support low-income workers and weaker parts of the economy.

The result projected in the budget is for a solid short term growth outlook (4.25% in FY22) followed by a significant degree of uncertainty regarding FY23 and FY24.

Our view is that the growth in those later years will be stronger than the budget forecasts and it will be growth that is sounder and less reliant on government largesse – more so if COVID-19 is well managed.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire. Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics

2 stocks mentioned