Are the worst of Australia’s property falls behind us?

The most dire predictions for Australian house prices of 25% price peak-to-trough falls or more since early 2020 haven’t played out.

Instead, average national prices fell by just 4% between March and December last year, with even the sharpest-falling market of Sydney booking a decline of just 7%, according to research from REA Group’s property data business, PropTrack.

What’s going on? And what’s the likely outlook for Australian house prices from here?

In the following wire, I gathered insights from a couple of industry insiders:

- Pete Wargent, co-founder of AllenWargent Property Buyers

- Eleanor Creagh, senior economist at REA Group.

“The bottom of the market has been and gone”

“Talk of a crash probably isn’t the right framing,” says Wargent, pointing out that prices instead hit all-time nominal highs in the third quarter of 2023.

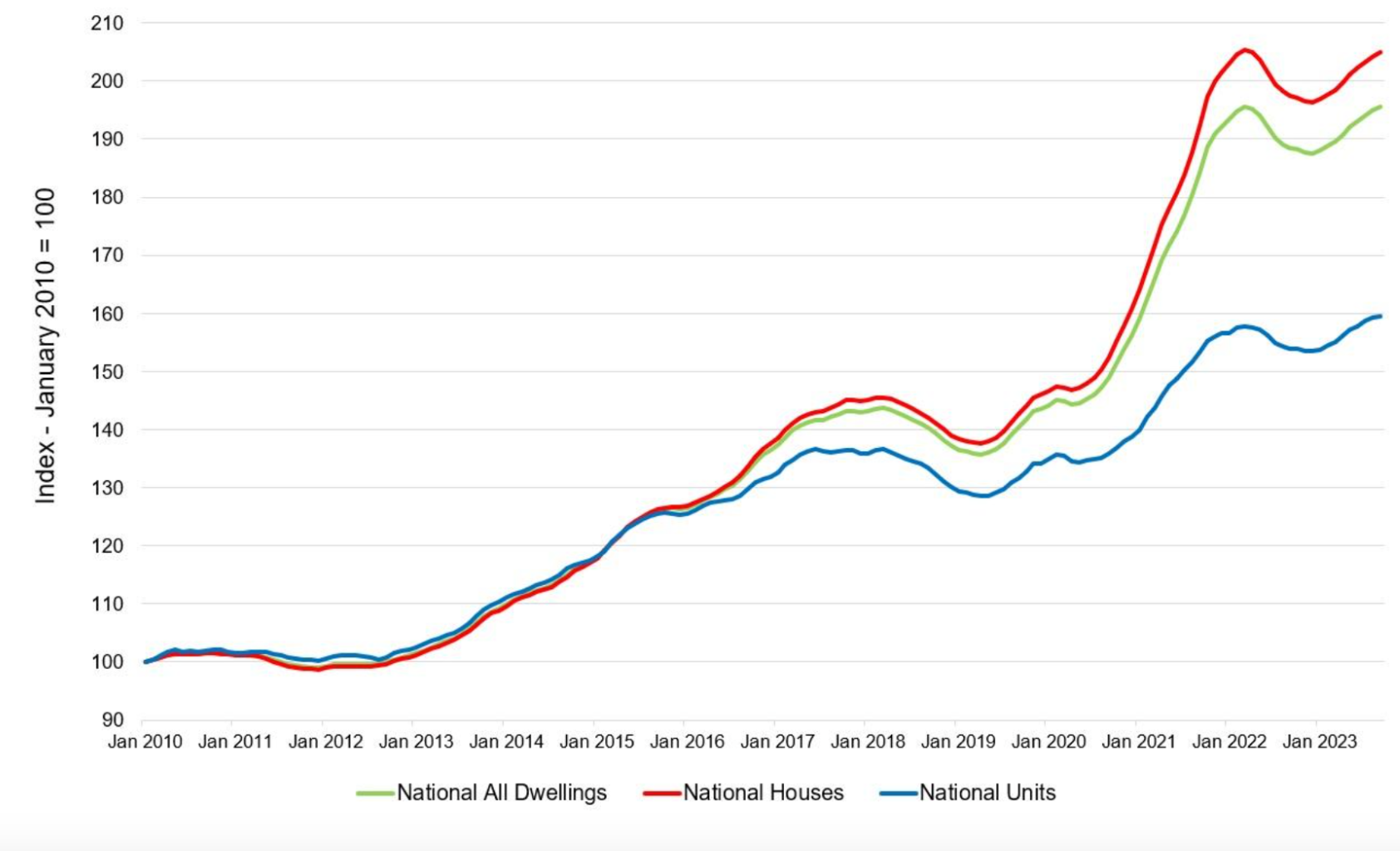

Wargent notes that the national average home price is now up around 35% since talk of a property crash dominated the narrative in the early pandemic period of 2020, according to data from SQM Research.

“There’s a bit more nuance to this story, though, and this includes the marked underperformance of the capital city units market since the time of the 2016 construction boom, an undershoot that has become even more pronounced still since the onset of the pandemic,” he says.

Proptrack indices - capital and regional cities

Wargent believes the bottom of the market has long since come and gone, with the “peak fear” phase of the cycle passing towards the back end of calendar 2022.

This is a view echoed by REA Group’s Eleanor Creagh, who notes that September marked the ninth consecutive month of price highs.

After falling 4.10% from March 2022 to December 2022, national prices are now up 4.31% from the low point recorded in December and 3.75% higher than a year ago, according to Proptrack data.

“The recovery is now pretty firmly entrenched. Those accelerated price falls many were expecting into this year are now a distant memory,” she says.

“This year is shaping up to end with above-average annual growth in many markets, despite rates being substantially higher.”

What’s driving this?

Both Creagh and Wargent highlighted the following factors:

Australia’s strong rebound in overseas migration, which saw our population hit 26.5 million at the end of March, surpassing our pre-pandemic level, according to ABS data.

Rental vacancy rates at record lows, with high rental prices encouraging some of these would-be renters to bring forward home purchase plans

A resilient labour market, with an unemployment rate of 3.7% at near-decade-lows, according to ABS data.

“A shortage of dwellings is now in evidence and suburban home prices are in many cases testing new highs in nominal terms, in spite of a significant crunch for borrowing capacities,” says Wargent.

Aside from record-high population growth, the replacement cost of property has soared. Wargent says this has been driven largely by an uplift in residential construction costs, which for houses are up by about a third since the onset of the pandemic. For medium- and higher-density projects, building costs are up by closer to 50%.

“Residential building approvals over the past year are running at around 170,000, which is the lowest in a decade, so the dwelling construction pipeline is likely to thin out ahead," Wargent says.

He also notes that residential building approvals over the past year are running at around 170,000 – the lowest in a decade – contributing further to the outlook for a thinner pipeline of new residential construction.

“A self-fulfilling prophecy”

REA Group’s Creagh emphasises the lower volume of homes listed in the first half of this year, concentrating buyer interest around fewer properties for sale and pushing home prices higher.

“We probably would’ve seen the recovery was much more fragile if we hadn’t had that subdued listings environment in the first half of this year. Now it’s become more of a self-fulfilling prophecy,” she says.

“The nine consecutive months of home price rises, interest rates that look to have peaked, and more certainty around future borrowing costs are likely to draw people off the sidelines.

Another point Creagh emphasises here is the upgrade activity among existing homeowners, who have been adding to the buying volumes, spurred on by the equity gains of their existing properties..

The mortgage cliff

The so-called “mortgage cliff” was widely tipped as a looming catastrophe for Australia’s economy as rising inflation led to the RBA to start hiking rates last May. Many expected a spike in home loan defaults and flow-on effects in the local economy as more than 880,000 low-fixed-rate mortgagees transitioned to higher rates.

But it hasn’t played out that way, with no deluge of forced home sales, explains Creagh.

“It’s no doubt a challenging period for many households, who are forced to make budget adjustments. But we’ve seen mortgage-holders prioritise mortgage repayments and dial back discretionary spending elsewhere – or even sell their home,” she says.

“The strong labour market conditions have also played into this in providing a safety net and job certainty.”

Creagh also emphasises that the tighter lending standards in place since the pandemic struck have meant higher buffers for mortgage-holders.

Other elements include the mortgage safety that has shored up this part of the market, including lenders’ dedicated “hardship teams” helping find solutions for cash-strapped mortgagees.

As Creagh explains, these include payment suspension periods and alterations to loan terms, “which prevent the majority of borrowers experiencing this fixed-rate expiry and ending up having to sell their homes.”

Wargent echoes these views, noting that the stock of homes remain far below its half-decade average for this time of year, “even as the long-awaited spring selling season has kicked into gear”.

“The biggest impact of interest rate hikes appears likely to show up in slowing household consumption rather than in mortgage arrears and defaults, at least in the event of the hoped-for ‘soft landing’ scenario,” Wargent says.

He also emphasises “the lowest unemployment rate in half a century” and a job vacancy rate that has stayed at historical highs, “at least for now”.

Which Aussie markets fared best - and worst?

Regional property markets have fared the best, with Perth the strongest, closely followed by Adelaide. Creagh notes that Perth prices are up 9.42% this year, and Adelaide prices have gained 8.31%.

Sydney has also proved among the most resilient markets. After booking the biggest falls in 2022, house prices in Australia’s most populous city are up 7.9% in 2023 and unit prices are up 5.2%. But Brisbane is the standout, the first Australian state or territory to recover all of 2022’s price falls and return to its peak.

What’s ahead?

Creagh expects mortgage rates to begin moving lower in the second half of 2024, anticipating this will see the rise in house prices continue - though perhaps less sharply.

“As the economy continues to slow as is expected in the coming months, and the unemployment rate reduces, it begs the question as to whether the strong price rises we’ve seen in recent months will continue.

This is a view shared by Wargent: “Housing prices, overall, appear most likely to grind higher in the capital cities over the remainder of 2023 and 2024.”

He also expects that the higher volume of listings and affordability constraints will, over time, most likely curtail the pace and extent of price growth.

“If interest rates do begin to fall in H2 2024 - and notably if the market’s prudential regulator APRA eventually releases the now-unnecessary 3 percentage points lending assessment buffer settings - then a double-digit pace of price gains would be on the cards," Wargent says.

What about regional markets?

On the other hand, for some of the regional markets that overshot during the pandemic, there is probably still 10% to 20% downside risk due to the marked shift in mortgage rates, Wargent says. He calls out the eastern seaboard’s “sea-change” locations, anticipating a big pull-back could lie ahead.

“During the pandemic, the sea-change locations were the biggest winners, with markets such as Byron Bay, Noosa, and many other coastal regions experiencing a spectacular price boom,” Wargent says.

“The ‘rush to the regions’ dynamic has now partly reversed, however, and to some degree, we are seeing the opposite impact on prices.”

Coming back to a point made earlier by Creagh, Wargent says the reopened international borders should spark a revival of demand for capital city units and apartments.

“Most new arrivals will tend to be renters in the capital cities, especially in Sydney and Melbourne. Population growth is also still extraordinarily strong in Perth, Brisbane, and south-east Queensland more broadly," Wargent says.

“This is sparking a revival for capital city units and apartments, with prices and rents now rising, and sometimes appreciably.”

Creagh anticipates there may be wider variance between markets, anticipating the smaller capital city markets of Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane - where housing is relatively affordable - will continue to do better.

“We haven’t seen the same pickup in home listings activity as we saw in Sydney and Brisbane, which is creating more competitive market conditions,” she says.

3 topics

1 contributor mentioned