Are you really a long-term investor?

Everyone says they’re a long-term investor. But I don’t think that is true.

Their actions betray their intentions.

That’s because everything in financial markets is about short-term thinking. Brokers want you buying and selling. Stock ideas and recommendations are a dime-a-dozen.

There’s Trump trades, and Fed trades…China trades and inflation trades.

There’s a trade for every occasion!

Buy this, sell that…

The financial services industry knows that investors want rewards now, not later. So nearly all advice is geared towards satisfying those wants.

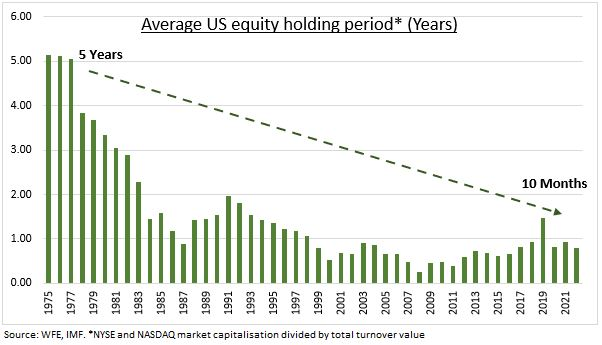

As you can see in the following chart from Ben Carlson’s A Wealth of Common Sense blog, the trend over the decades is towards less investing and more trading, as everyone seeks short-term gains.

Source: A Wealth of Common Sense

Yet as this next chart shows (also from Ben’s blog), the odds of success are much greater the longer your view.

Source: A Wealth of Common Sense

According to a 2020 World Bank study, Australian fund managers turn over around 70% of their portfolio each year (on average).

Think of the fees and taxes you pay when turning your portfolio over that quickly. Over the long-term, this behaviour compounds negatively.

If you want to compound wealth in a positive way, you should do less, not more.

The problem is that we are too impatient and short-sighted to see the benefits of long-term thinking and investing.

In our pursuit of short-term gains, we sacrifice any chance we have of generating long-term rewards.

There’s an excellent quote in Money Masters of Our Time, by John Train that sums this up nicely. In the chapter on Phillip Fisher, he writes:

‘…the investor who attempts the impossible abandons his only hope of doing well.’

The short-term punt is alluring but low probability. The long-term investment is boring but higher probability.

I want boring over alluring. The outcome is much more assured. And potentially much more rewarding.

Remember that book, The Marshmallow Test? It sought to determine what drives short-term impulsive decisions versus the benefits of delayed rewards.

It turns out that the kids who resisted the urge to eat the marshmallow NOW did much better than the impulsive tykes later in life.

The ‘marshmallow now’ eaters employed ‘hot system’ thinking. As the author, Walter Mischel, writes:

‘Immediate rewards activate the hot, automatic, reflexive, unconscious limbic system, which pays little attention to delayed consequences. It wants what it wants immediately and steeply reduces or “discounts” the value of any rewards that are delayed.

‘It’s driven by the sight, sound, smell, taste and touch of the object of desire… That’s why smart people in the public eye, like presidents, senators, governors, and financial tycoons, can make stupid decisions when immediate temptations lure them to overlook the delayed consequences.’

But the delayed-reward people employed ‘cool system’ thinking:

‘Delayed rewards, in contrast, activate the cool system: the slower to-respond but thoughtful, rational, problem-solving areas of the brain’s pre-frontal cortex that make us distinctively human and able to consider long-term consequences.’

It makes sense then that if we think about investing with our cool system, we will do much better in the long term than those employing hot system thinking (which is the majority of the market).

That last point is important. If the majority of the market uses its ‘hot system’ and engages in short-term decision-making, where do you think the advantage is?

It’s in cool system thinking. In optimising for long-term rewards over short-term gains.

Charlie Munger once said: ‘The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.’

Legendary trader Jesse Livermore said the same thing:

‘After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It always was my sitting. Got that? My sitting tight!’

Jesse shot himself in a New York hotel cloak room. He did a little too much thinking and not enough sitting.

He got rich, and poor, quickly on a number of occasions. But he knew what he should have done.

Munger is the better role model…

So let’s learn from him.

Over the years, I have sold early way too many times. Perhaps you have too? You may have wanted to avoid the pain of a short-term loss or to take a short-term gain.

We’ve all been there.

But if we consciously optimise your portfolio for long-term gains, it will be much easier to avoid making the mistake of impulsive selling in the future.

There is a deep truth to this idea. That’s because it applies in life too. We’re told from a young age there are no shortcuts in life. Only hard work and reward for effort put in.

Yet the market is full of people thinking shortcuts exist. People want rewards for little effort!

But if life doesn’t reward that behaviour, why would the stock market?

The truth is, it won’t. But hope is a powerful force. And people want to believe in the chance for easy riches.

The market can deliver immense wealth for you if you buy good companies at a good price. Then, wait and let compounding do the rest.

Or, as Jesse Livermore said, sit tight!

To be clear, not every company you buy will be a multi-year holding. Cyclicals, commodities, and companies that have fallen out of favour for whatever reason are the ones you want to buy cheaply and sell when they’re popular again.

But having a core holding of well bought companies, owned for years, is where the really big returns will come from, and where optimising for the long-term will really pay off.

Want more like this?

Enjoy unfiltered investment analysis? That's just a taste of the daily insights at Fat Tail Daily, covering everything from tech to miners to economic trends. Expand your perspective - subscribe for free here.

2 topics