Aussie accounting shenanigans

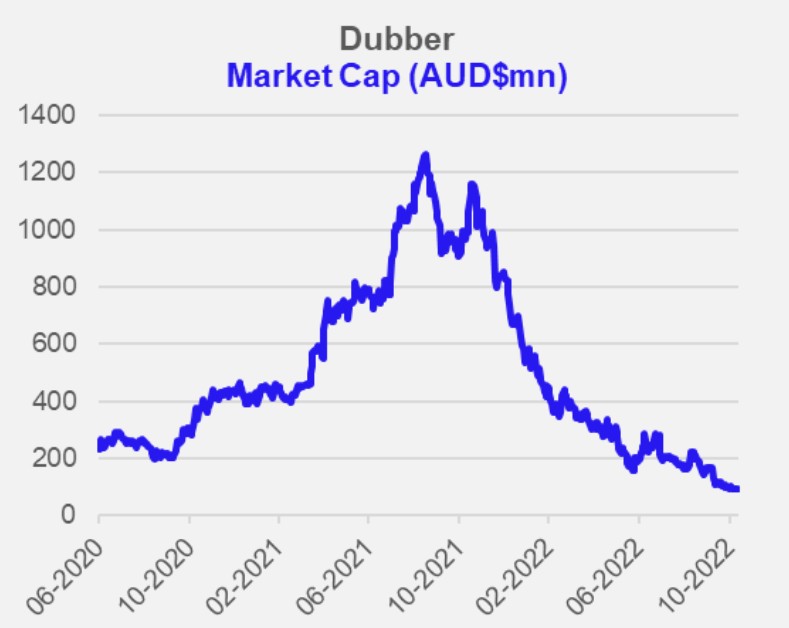

The year was 2021. Investors were swept up in the euphoria of roaring stock prices and tech-fueled optimism. Behind the scenes, one ASX tech company was generously massaging its revenue numbers to support a carefully crafted growth narrative - in the hopes of becoming a market darling. It was working. Top line was accelerating, its market cap hit $1.2 billion, institutional banking sales desks were pitching it to investors citing "Major Growth Ahead!", helping it raise over $100 million cash from investors.

Since that time, the company has lost 98% of its market value, as investors eventually cottoned on to the questionable revenue recognition which exaggerated the apparent momentum. The company in question is Dubber (DUB.AU). This article covers the red flags on display in 2021 - readily accessible to anyone willing to read the financial accounts - serving as a cautionary tale for investors to learn from.

Dubber is a software company which sells cloud-based call recording software. It was founded in 2011, backdoor listed in 2015, and faced public criticism from its major institutional shareholder in 2017 for poor execution, capital allocation & Board governance (1).

Notwithstanding significant cash burn and the failure to generate any meaningful revenue prior to 2019, Dubber managed to survive by continually finding new investors willing to tip capital in on the promise of future revenue growth with an endless stream of announcements about contracts, partnerships, MOUs, and pilots with notable customers.

In 2019, growing telco relationships and active users began to see revenue materialise. Management introduced an unaudited 'annualised recurring revenue' ('ARR') metric in 2020 and exited the calendar year with $28 million reported ARR growing 168% year on year. In early 2021, Dubber announced a deal with AT&T and Zoom. Investors, anticipating growing business momentum, drove the share price higher, doubling to $2 over April and May of 2021. By July 2021, Dubber announced it was now a 'standard feature' in Cisco's Webex product, its ARR had hit $39 million and the company completed a $110 million capital raise just shy of $3 a share.

Red Flags Emerge

Many investors have observed the stereotypical earnings re-classifications often presented in 'management accounts' ( 'earnings-before-XYZ'). The difference in management numbers versus those presented under official accounting standards can provide a useful means to gauge the credibility & trustworthiness of management.

While earnings are easily massaged due to the subjective exclusion of costs, management representation of revenue is often harder to manipulate and therefore more readily accepted by investors. Dubber, however, is a useful case study in the latter.

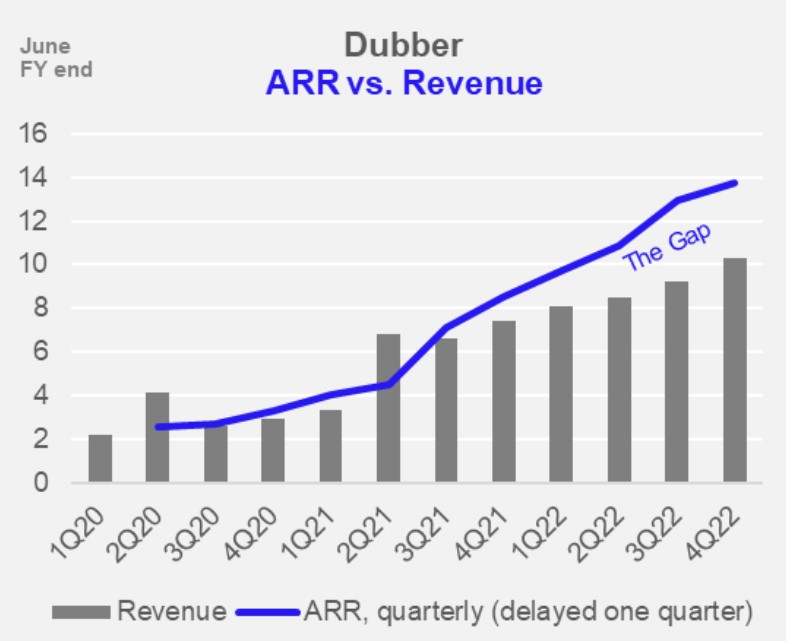

Deterioration in the reliability of reported metrics began to appear in FY21, as reported ARR and actual revenue began to diverge.

There were two problems here. Firstly, ARR was defined by the company as 'the next 12 months of subscription revenue net of any incentives'. Therefore, the ARR run-rate reported at the end of a given quarter, should readily translate to revenue recorded in the next. Take for example, March 31st 2021, the ARR was reported as $34 million which would have predicted $8.5 million in subscription revenue between April and June 2021. Instead, only $7.4 million of total revenue was reported, which included an undisclosed amount of R&D grants, COVID job-keeper payments and interest income. Taking the full year disclosure as a proxy, ~12% of income was not subscription related, putting a rough estimate of the quarter's subscription revenue at ~$6.5 million. A far cry from the unaudited ARR metric investors were focused on.

The ARR-versus-revenue gap continued to widen in subsequent periods.

The next red flag came in the release of the FY21 annual report in October 2021.

Buried in the ‘Notes to the Financial Statements’ was disclosure that a significant portion of recognized revenue over FY20 and FY21 had come from a major Australian customer which owed it a lot of money ($10.9 million at the time), and had not made any payments.

While it was clear this customer was not paying up by June 30th, 2020, the disclosures indicated Dubber had continued to accrue meaningful revenue from the same customer over FY21. In fact, 21% of reported FY21 service revenue had been derived from this customer.

At this point investors could observe an unaudited ARR metric that was not translating into recorded revenue, and a revenue line itself which was potentially materially overstated.

And yet, Dubber still sported a $1 billion market cap by December 2021.

More questions followed with the release of 1H22 accounts.

Accounts receivable in 1H22 - revenue invoiced to clients, which are not yet paid - had blown out to nearly $25 million. To put that in context, it implied 'receivable days' of over 250, despite having disclosed receivables terms of 30 days.

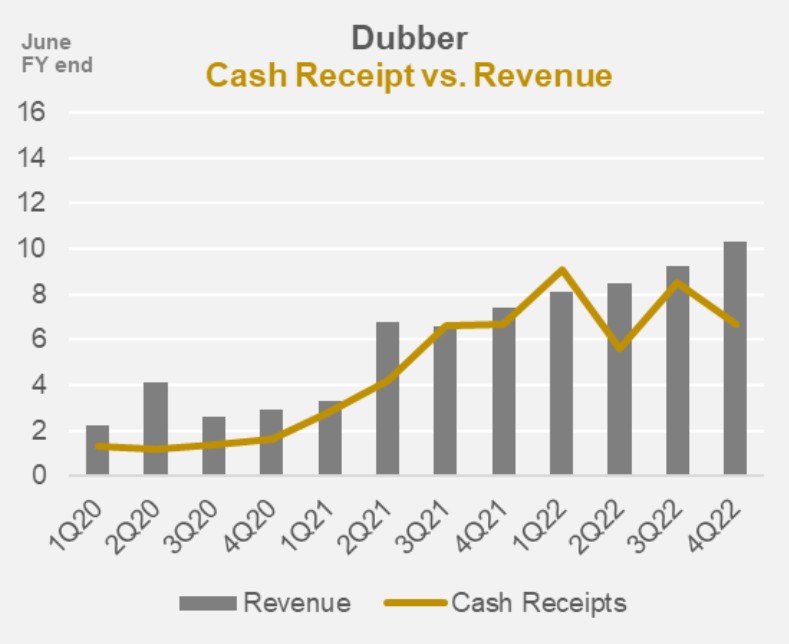

Cash receipts then began to deteriorate over the remainder of FY22.

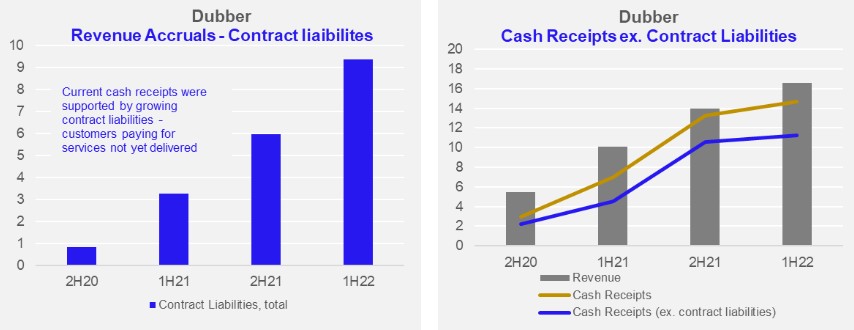

While this was observable at face value in the chart above, cash receipts were bolstered by the emergence of "contract liabilities" on Dubber's balance sheet - essentially services it had been paid for, but not yet rendered for clients. This was an additional source of "cash receipt" which was yet to contribute to revenue, but improved the optics of revenue-to-cash conversion in the reported period.

To put all this in context, through Dubber’s peak euphoria period in 2021, it’s reported ARR averaged $42 million, while recorded revenue was lower at $31 million, total cash receipts were lower still at $28 million, and if we remove the increase in contract liabilities (payments for services not yet rendered), operating cash receipts were lower again at ~$22 million.

Postscript

Dubber's shenanigans came home to roost in August 2022 when it failed to release audited accounts to the ASX and was suspended from trading. Audited accounts later released in October saw recorded revenue slashed by nearly 30% with a major receivable impairment and the CFO's resignation. The company ended 2022 with a market cap of $150 million.

Accounting red flags are rarely material enough in isolation - instead, investors should consider how an accumulation of smaller flags combine to inform a view of financial risk and insights into the credibility and trustworthiness of management.

4 topics

1 stock mentioned