Beware the inflation snap-back: today's inflation isn't 1970s (part 1 of 4)

Runaway inflation is the theme du jour. “Protect your portfolio from hyperinflation” scream headlines from investment newsletters. I have an alternative scenario for you. Current inflation is supply-chain and commodity bubble-based, temporary, and the recent price signals will actually create the opposite effect.

It is a detailed argument. So, I’m going to present the alternative scenario in four parts:

- Part one: inflation today is not the same as inflation in the 1970s.

- Part two: the China inflation problem - commodity inflation is far more leveraged to Chinese stimulus than developed market stimulus. And the signs are ominous.

- Part three: the inventory supercycle “pig in the python”. The price signals of today are creating the excess capacity of tomorrow.

- Part four: how to position your investment portfolio for the inflation head fake

To stay updated on the rest of this series and be notified of each part, click the follow button to the left or at the bottom of this post.

Why today’s inflation is not the inflation of the 1970s

We have been warning for months that markets will get carried away with extrapolating short term inflation long into the future. This month we saw high inflation prints in the US and we expect inflation will stay high in the coming months. But we expect it to be transient. It is not the same as the inflation of the 1970s for four reasons:

- Base effects.

- Economic orthodoxy has been overengineered to prevent inflation.

- Inflation expectations

- Changing economic structures

- Technological innovation

Reason 1. Base effects

Most of the inflation is either in the supply chain or comes from low base effects, both of which will pass.

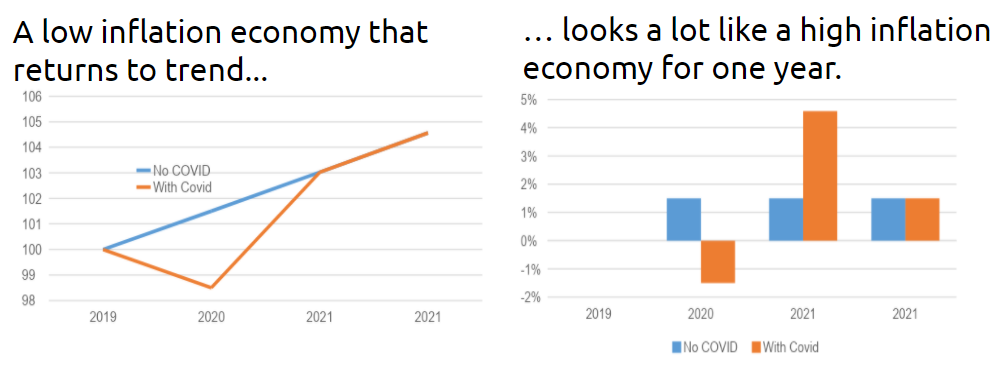

Stimulus cheques do create inflation by boosting demand. But a one-period inflation spike does not create ongoing inflation.

Reason 2. Overengineered Economic Orthodoxy.

Inflation is not well understood. Most central banks have been trying to create inflation for the last decade. And failing. The Bank of Japan? 30 years.

In 2010, many prominent economists were so sure hyperinflation was coming that they wrote an open warning to the then head of the US Federal Reserve. No inflation.

This isn’t to say we know nothing about inflation. But it does mean that we need to approach inflation forecasts with skepticism and keep an open mind on outcomes.

The olden days

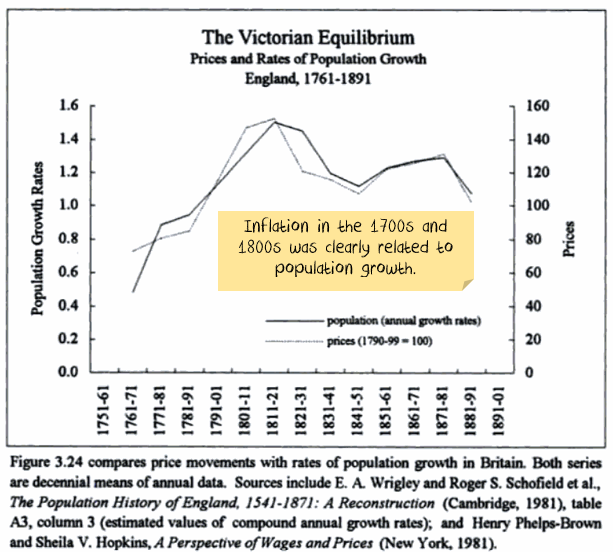

Pre-1900, inflationary bouts were common. They tended to coincide with either population growth, famines, war or monetary debasement.

Today’s economies are different. The factors that cause inflation in agricultural societies are not the same as in a modern economy.

Population growth will still affect inflation, but population growth is very low relative to historical levels.

As food has become a much smaller part of the family budget. Agricultural employment has shrunk to a fraction of historic levels. Global supply chains mitigate regional crop failures. The net effect is that inflation is a different beast in the modern era.

Stagflation era

The world struggled with both high inflation and high unemployment for most of the 1970s and 1980s. This is the scenario that technocrats are looking to avoid.

It is worth noting three other important factors:

- Monetary system: In 1974, the world monetary system changed significantly. The US severed their link with gold, meaning that we were reliant on the will of politicians to keep inflation in check. That didn’t work.

- Oil prices: The rise of the OPEC oil cartel saw a significant increase in oil prices. The flow-on effect of increased transport costs bounced from one industry to the next, exacerbating high inflation.

- Big governments: Many industries were government-owned. Telecommunications, power, airports, infrastructure. Many were not particularly efficient.

High inflation becomes the norm in the 1980s.

Inflation expectations became entrenched. Employees demanded continual wage rises to offset the effect of the higher expected inflation.

Companies had to raise prices to keep profitable. Meaning employees needed a pay raise. Rinse. Repeat.

The pendulum swings to the other side

Stagflation was cured in the 1980s. The narrative is inflation was solved by the US central bank, which raised interest rates high enough to stamp inflation out. i.e. the central bank was prepared to cause a recession to “anchor” inflation expectations.

Just as importantly, new rules were enacted to “ensure” inflation wouldn’t return:

- Monetary System: Independence from political intervention for central banks, inflation targets, various rules on government money printing.

- Oil Prices: The best solution to high commodity prices is high commodity prices. A wave of investment and increased supply meant oil prices stopped rising.

- Deregulation: A range of industries changed from public to private ownership, lowering costs.

Keep in mind that the late 1970s and 1980s were the start of a new monetary experiment. Runaway inflation created new rules. Arguably, the pendulum has swung too far. The steps taken to prevent inflation have entrenched disinflation.

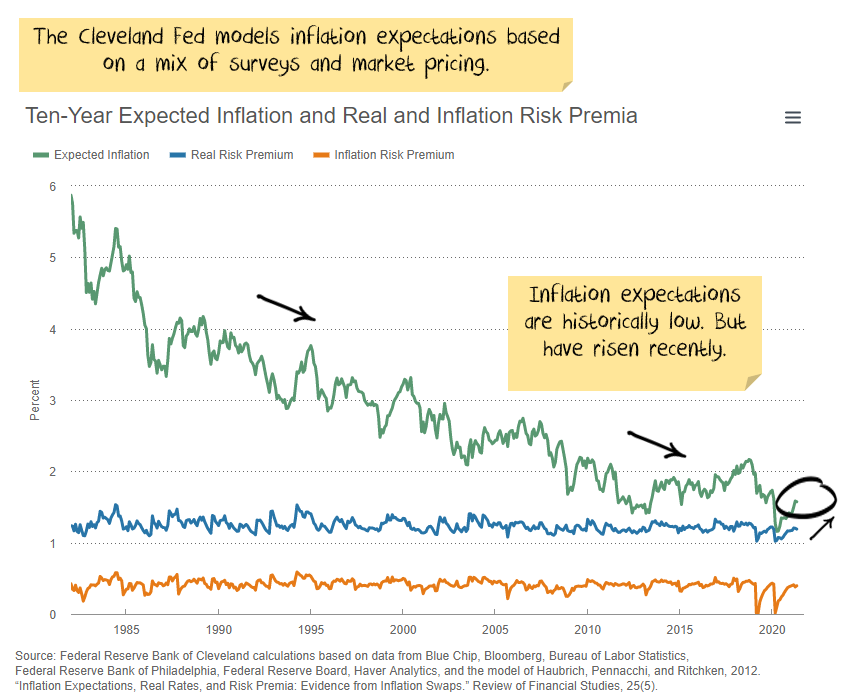

Reason 3: Now, low inflation becomes the norm

Low inflation expectations became entrenched. Employees stopped demanding continual wage rises. Unionisation rates plummeted.

The importance of this series is that inflation expectations change slowly. A jump to higher inflation is unlikely to be a one month or one quarter phenomenon. It will take years to reverse entrenched expectations.

At the end of the second world war, US inflation jumped as the economy re-opened. People suddenly demanded cars, white goods and clothes from factories that had been reconfigured to make tanks and battle fatigues. Inflation quickly returned to 2% and inflation expectations remained grounded. While the scale of changes to production is not in the same ballpark as World War II, we believe the disruption to supply followed by a burst of demand will be similar.

Reason 4: Changing economic structures

The world of the 1970s and 1980s has changed in a number of fundamental ways.

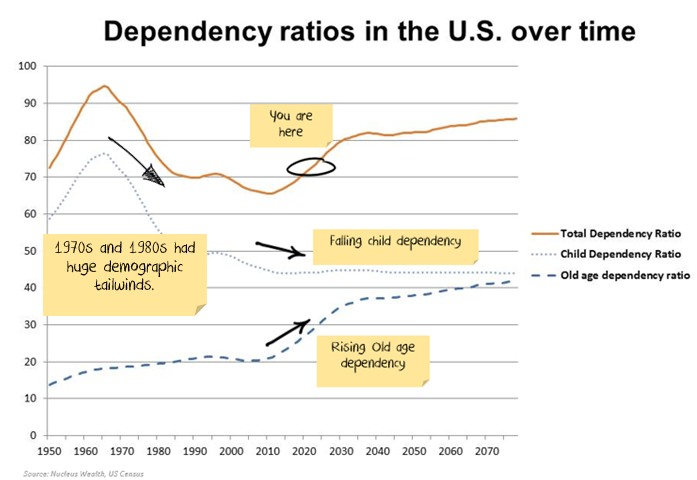

Demographics

Demographics were a demand tailwind as the number of people working relative to those not working increased dramatically.

Today we have the opposite problem.

Trade

In the 1970s and 1980s, world trade was 25-30% of total world GDP. Today it is closer to 45%. Put simply, the supply curve for manufactured goods is a lot flatter and there is significantly more international competition to hold prices down.

In the 2000s, China entered the World Trade Organisation and started routinely exporting deflation in the form of lower prices for manufactured goods.

With work-from-home becoming far more widespread for companies, it is likely this trend will extend to services. Put simply, it is likely the supply curve for many services will be a lot flatter and there is significantly more international competition to hold wage costs down.

Manufacturing

In most developed countries, manufacturing has shrunk as a proportion of the economy by a third since the 1980s. This puts even more focus on wages, as wages are the largest cost for service companies.

The structure of developed economies has changed.

Debt

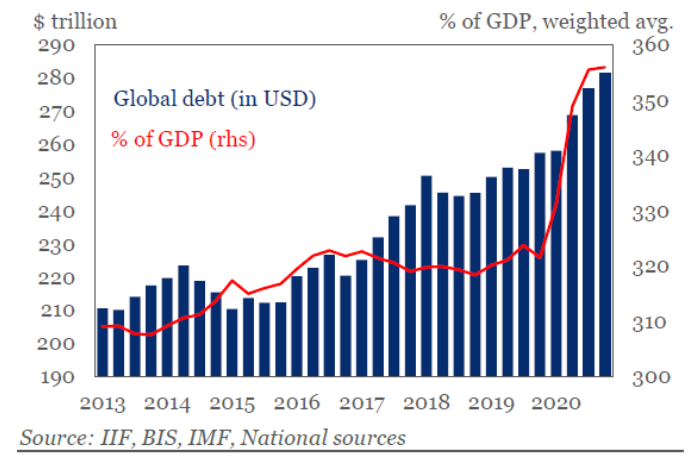

Debt is a two-edged sword when it comes to inflation. Increasing private debt levels can drive inflation higher while the debt is accumulating.

However, unless private incomes also increase, high debt levels serve to decrease demand.

i.e. if the debt is created for productive assets like buying new businesses or infrastructure, it can quickly pay for itself.

Suppose the debt has been accumulated in non-productive assets like bidding house prices higher. In that case, there is more likelihood that it will slow inflation.

The 1970s and 1980s saw significant financial reforms and increasing debt availability. Consumer debt grew rapidly.

Now, debt levels are high. Wage growth is low.

Reason 5. Technological disruption

Technology is inherently deflationary. Incremental improvements are at the heart of capitalism. In recent decades the internet disintermediated entire industries, reducing costs, increasing competition and lowering inflation.

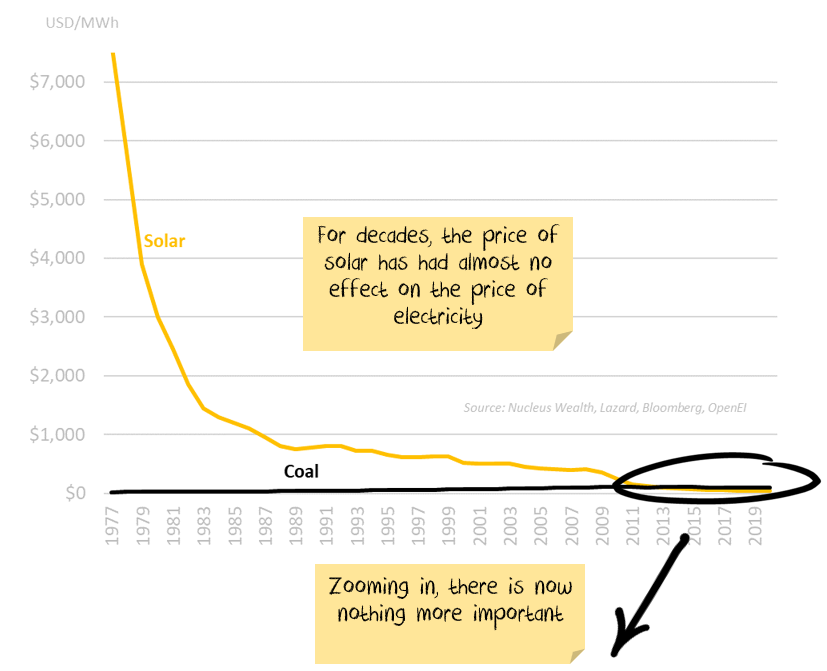

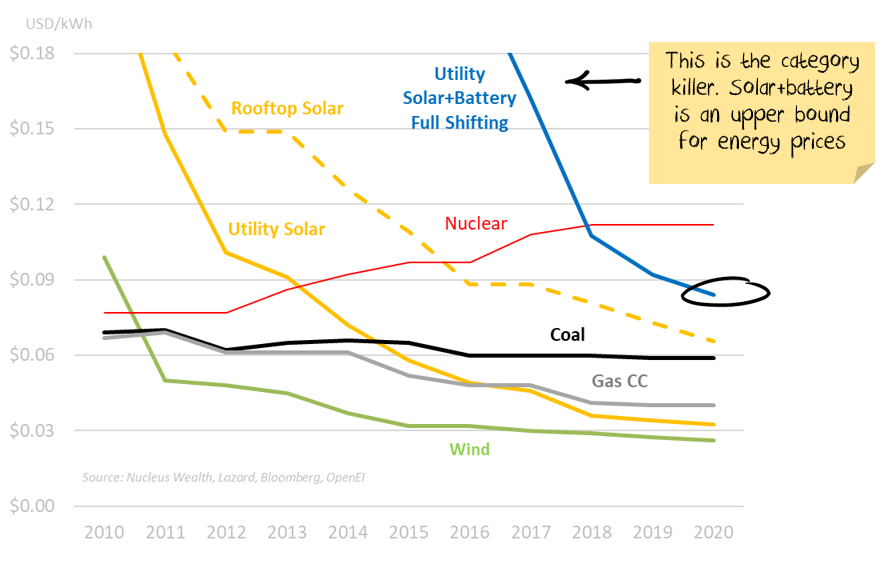

Energy

In the next few decades, power grids will either evolve or collapse. The age of centralised energy is all but over. Ahead lies a radical evolution to the decentralised and local. Moreover, as it is completed, energy costs will continue to decline every year, sourced from sun and wind every day and stored in little boxes of chemicals.

The productivity and income gains implicit in this are immense. Every bit as large as the steam and oil revolutions before it.

This effect is starting in high energy cost countries with good solar resources like Australia or the Middle East. But it will spread to other countries as costs continue to fall. The US has some of the cheapest energy costs in the world, so it is likely to impact the US more slowly than other countries.

Robotics

Any and every repetitive function in the economy is going to be inhabited by a robot. Everything from manufacturing to driving is in the cross-hairs.

Supply chain disruptions due to COVID have brought this issue to a position of importance for governments and companies. Trade tensions between democracies and China are accelerating this trend.

Technological advancement will destroy jobs. But the productivity gains that come with it will lift incomes for both capital and labour. This will create demand and investment in new and more efficient segments.

There will be a major question about the disruption of job losses. Done well, part of the productivity gains will be temporarily used to transition those who have lost jobs into the new economy. Done poorly, soaring unemployment will create political chaos.

Either way, the forces are deflationary.

The road to lasting, rather than transient inflation

Inflation is too much money chasing too little goods or services. Short-term issues like weather or supply chain bottlenecks do not create lasting inflation.

What can create lasting inflation?

- Demographic changes can create shortages and inflation. But population growth is low.

- Wage growth creates extra demand and is the best source of lasting inflation. But wage growth is as low as it has ever been in many countries. Wage growth will likely improve. But it is a long (long) way from being a problem.

- Energy. When oil prices rose by a factor greater than 10x from 1970 to 1980, this added persistently to supply costs. The levels were so high that companies had to pass on the costs. At the moment, many oil-producing countries are artificially reducing supply to keep oil prices high. As demand picks up this supply will return, and the higher prices have attracted commercial operators (US shale gas in particular) to expand supply. While electric vehicles are not yet cost-competitive for the average vehicle, battery costs continue to fall. That will limit how much the oil price can affect the broader economy over time.Just as importantly, in the 1970s and 1980s, weak consumer demand was not an issue. In the 2020s, it is. Higher oil prices act as an additional tax on consumers.

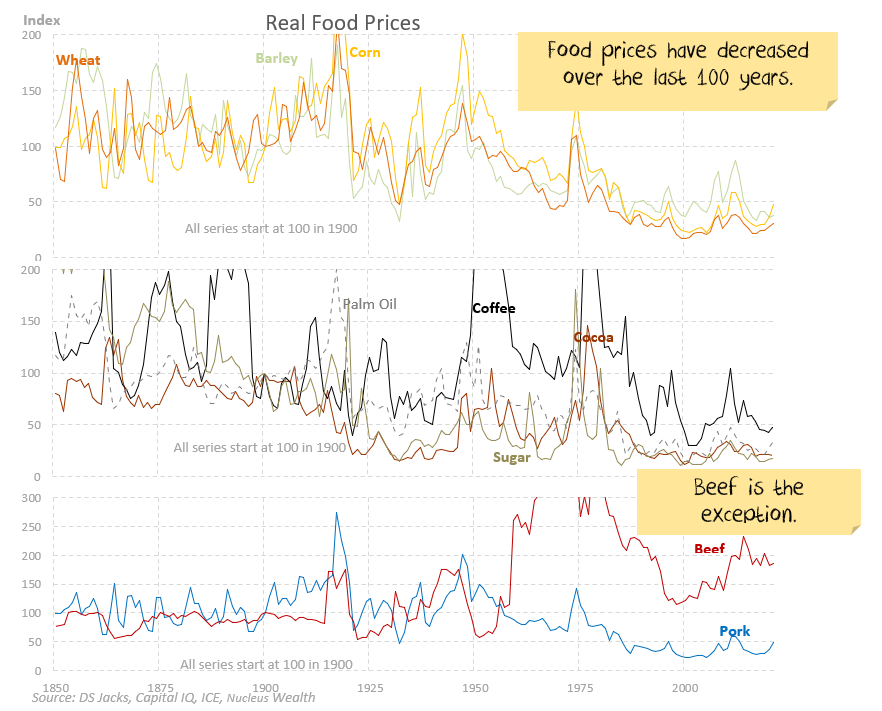

- Food. This is a bigger issue for emerging markets than for developed markets. Food prices have been deflationary over the long term.

Can there be a short term spike in food prices? Yes, but in developed countries, food is a low proportion of overall prices. And much of the cost of food is in the preparation costs, which is about wage inflation.

- Government fiscal policy that keeps creating demand even when the economy is at full capacity will create lasting inflation. Maybe this will be a problem. But capacity utilisation is a long way below prior levels. If this happens, it will be a number of years in the making.

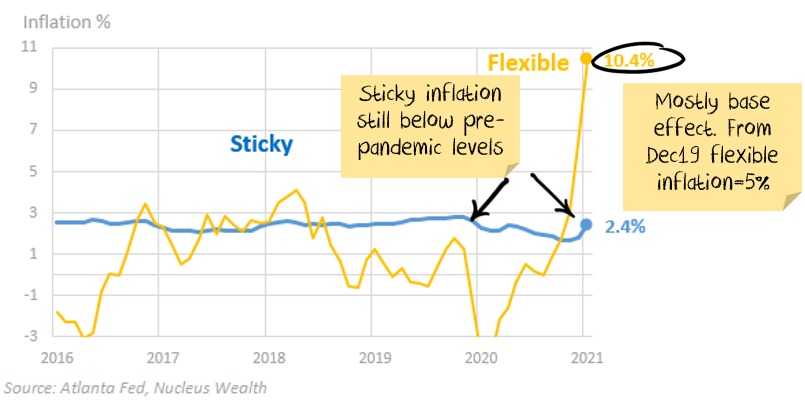

- Inflation in “sticky” priced items like rent, healthcare and other items with generally stable prices are likely to indicate lasting inflation. The inflation we are seeing at the moment is in “flexibly” priced items like fuel and food.

-

Permanent supply cost issues. These are the most difficult to get a read on. Clearly, there are short term supply issues in items like semiconductors, cars and building products adding to inflation. Additionally, companies have been trying to expand their low inventory levels to cater for potential future disruptions. There are anecdotal reports of companies stockpiling to ensure supply. All of these are, at best, transitory.

Inflation is not a “one-period” issue. For inflation to persist, the supply issues will need to be maintained. And maybe even get worse every year. This is not a likely outcome.

The worst scenario for inflation?- Buyers increase demand now to fill inventories and prices jump.

- Suppliers, encouraged by high prices, add more capacity.

- Buyers then drop back to normal demand levels once inventories are full.

- Suppliers capacity comes online just as buyers have filled inventories. Suppliers then need to cut prices significantly to offload their increased production. Prices fall below the original levels.

- A change in inflation expectations. At the moment, inflation expectations are anchored. There have been some recent surveys suggesting a jump in expectations.

Net Effect

The world has changed. The structure of today’s economy is radically different to the 1970s and 1980s.

It is still possible that governments will launch an ongoing spending spree which will drive inflation higher. But, given the announcements made so far, especially the pullback in Chinese and US fiscal impulses, the inflation we have seen to date, and the changes to the economy it is far more likely that the inflation will be transient.

Coming next: commodity inflation. Our contention is that commodity inflation is far more leveraged to Chinese stimulus than developed market stimulus. And the signs are ominous.

To stay updated on the rest of this series and be notified of each part, click the follow button to the left or at the bottom of this post.

Part two now available:

1 topic