Charts of the Week - The Powell spread, money market inflows and trouble in Sweden

.png)

This week’s charts begin with bearish trends: the “Powell spread” the Fed chairman uses as a recession indicator is the most inverted in decades, while housing markets are deflating at different rates around the world. We take a deep dive into suffering Sweden: inflation is worse than the European average, unions’ wage gains will be wiped out by price increases, and home values are sinking simultaneously across the country. In the US, money market funds appear to be the beneficiaries as bank deposits shrink, while in China, optimism that a boom would follow the great reopening has been tempered by sluggish global demand for exports. And turning to geopolitics, we track NATO’s leaders and laggards in defense spending.

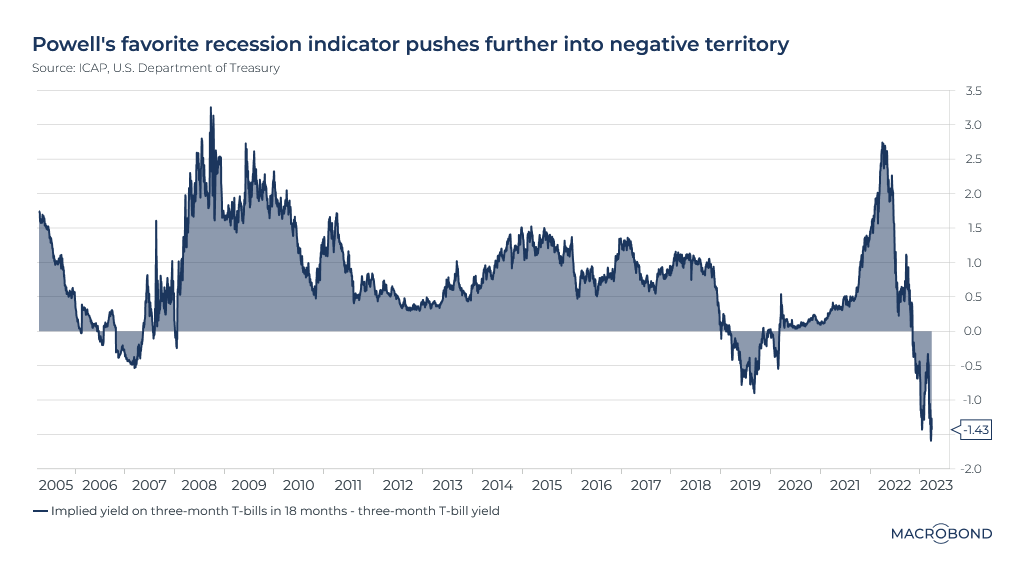

The Powell spread is looking recessionary again

We have previously written about the “Powell spread.” The Fed chairman’s preferred recession indicator, and a measure of investors’ expectations, it compares the yield on a three-month Treasury bill and its implied yield in 18 months’ time.

As Powell said a year ago, “if it's inverted, that means the Fed's going to cut, which means the economy is weak."

Our chart tracks the Powell spread using ICAP Forward rates. Recession watchers will note that after easing earlier in 2023, it’s now at its most inverted in at least two decades.

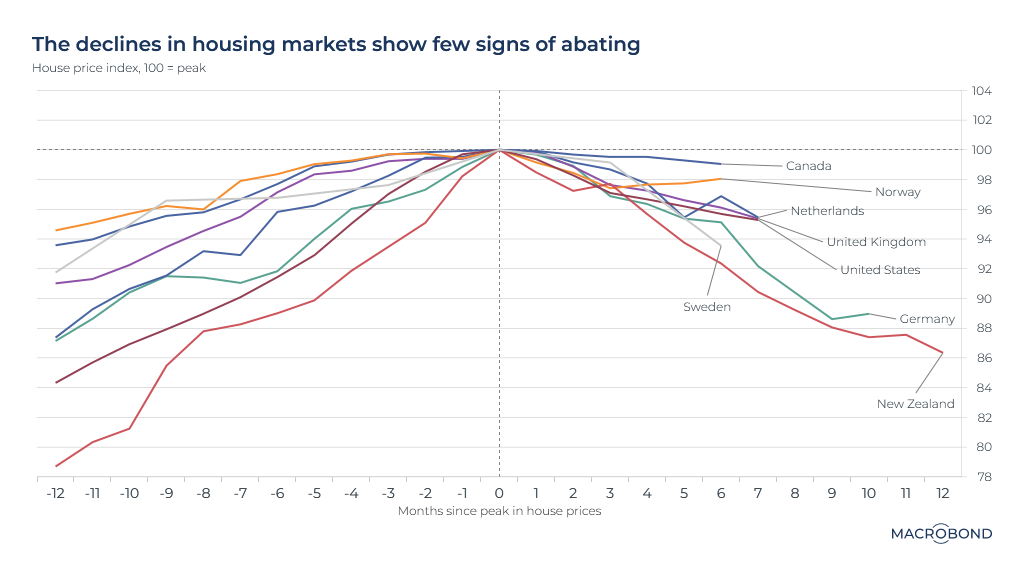

Housing deflates unevenly around the world

Across most of the developed world, higher interest rates and the more expensive mortgage payments that result are taking their toll on housing markets. In many nations, housing starts, transactions and prices are all contracting. In the US, a further hit could come from the recent bout of banking turmoil, which may cause smaller banks to tighten lending standards.

Our chart tracks home prices in several OECD nations in the months before and after their peaks. While the overall trajectory is similar, there is a divergence between markets. Countries with higher shares of fixed-rate mortgages, for example, tend to experience delayed rate impacts.

Canada stands out on this chart as it has barely lost ground from its peak. The Canadian panelist among the experts in our recent real estate webinar predicts a greater downturn is ahead.

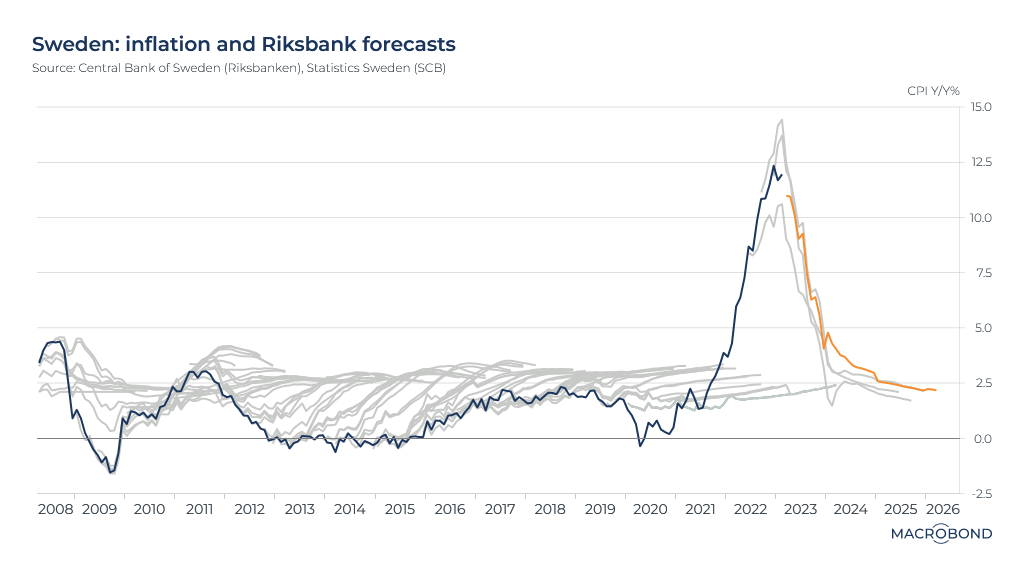

Sweden and its stubborn inflation

Inflation is hitting many countries, but it has proven especially strong and persistent in Sweden, exacerbated by the krona’s weakness against the euro. Sweden has also done less than some other European nations to shield consumers from the energy price shock.

Core inflation figures for February surprised on the upside. Under pressure from politicians, supermarkets recently announced price cuts.

Our chart tracks the nation’s consumer price index (CPI) and projects central bank forecasts, past and present. The grey lines show how the Riksbank overestimated inflation pre-pandemic; consistent forecasts for 2 percent CPI growth were followed by flat prices, circa 2012-2015.

The current forecast (in orange) doesn’t anticipate inflation will fall below 2.5 percent until the end of next year. That would still be a higher inflation rate than that seen at any time between 2011 and the pandemic.

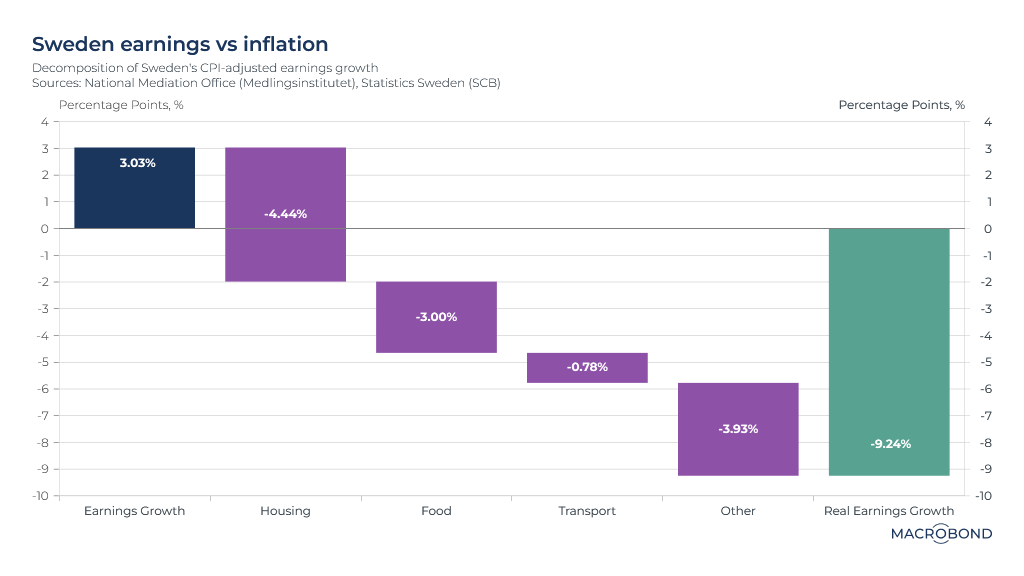

Swedish wages washed away by an inflation waterfall

Unsurprisingly, the inflation spike has impacted wage negotiations. Labour unions demanded an increase of 4.4 percent, turning down mediators’ offer of a 3.7 percent wage hike this year and 2.8 percent next year.

As our chart shows, even if the unions get what they want, real wage growth will be thwarted by the various components of inflation.

The last time real wage growth was so poor was in the 1980s. Nevertheless, the Swedish National Institute of Economic Research predicts that real wage growth will turn positive again next year.

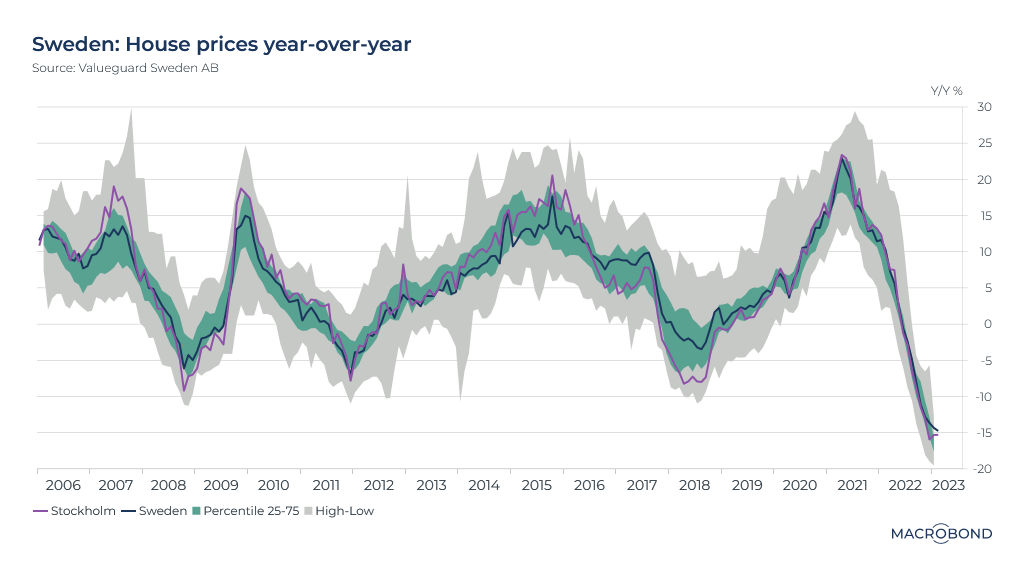

Floating rates mean sinking Swedish home values

As an earlier visualisation in this chart pack showed, Sweden is a nation where house prices are on a relatively swift downward trajectory. Given the prevalence of floating interest-rate mortgages in Sweden, tighter monetary policy has more of an immediate hit on household budgets.

This chart graphs house prices for Sweden as a whole, the capital city of Stockholm and the rest of the municipalities tracked by Valueguard – by way of percentile and “high-low” bands tracking the dispersion.

It shows how the decline is hitting the whole country at once – the first time that has happened since our data partner began compiling the figures. (One is reminded of the subprime crisis-driven US downturn, the first time there was a housing bust on a national scale.)

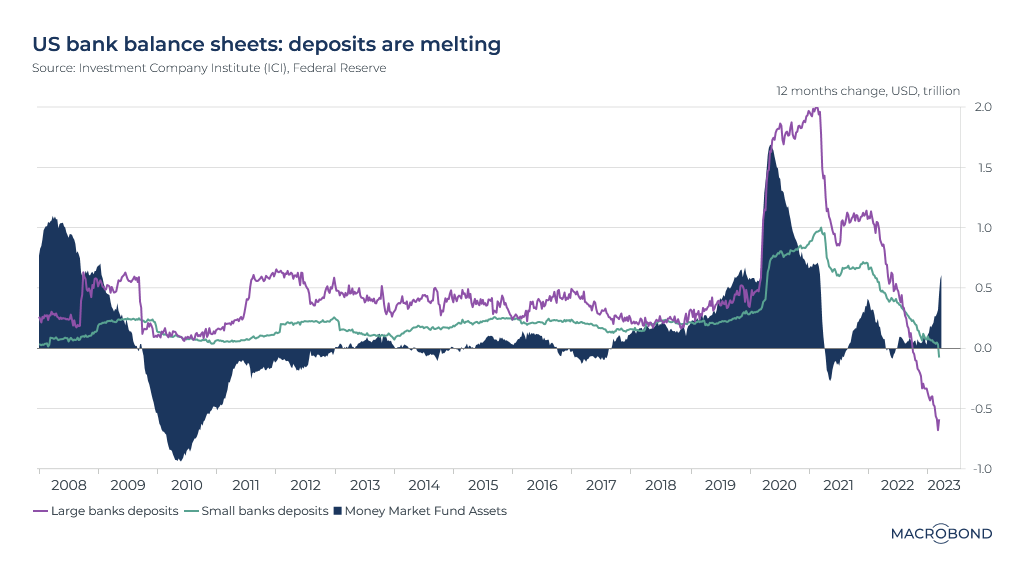

US bank deposits shrink as money market appeal grows

The Silicon Valley Bank affair focused minds on the FDIC’s deposit insurance limit of USD 250,000. Amid concern that deposits over that sum might not be safe, funds flowed out of smaller, regional US banks.

However, deposits at the 25 largest US banks had been shrinking well before the SVB crisis, and inflows from spooked regional bank depositors didn’t reverse this trend – as our chart shows. (The chart tracks the rate of change; inflows turn to outflows at zero on the Y axis.)

Where were the funds going? Probably into money markets.

As the chart shows, US money-market funds’ assets are now USD 500 billion higher than they were twelve months ago. After almost a year of steady interest-rate increases, low-risk assets are finally generating more appealing yields.

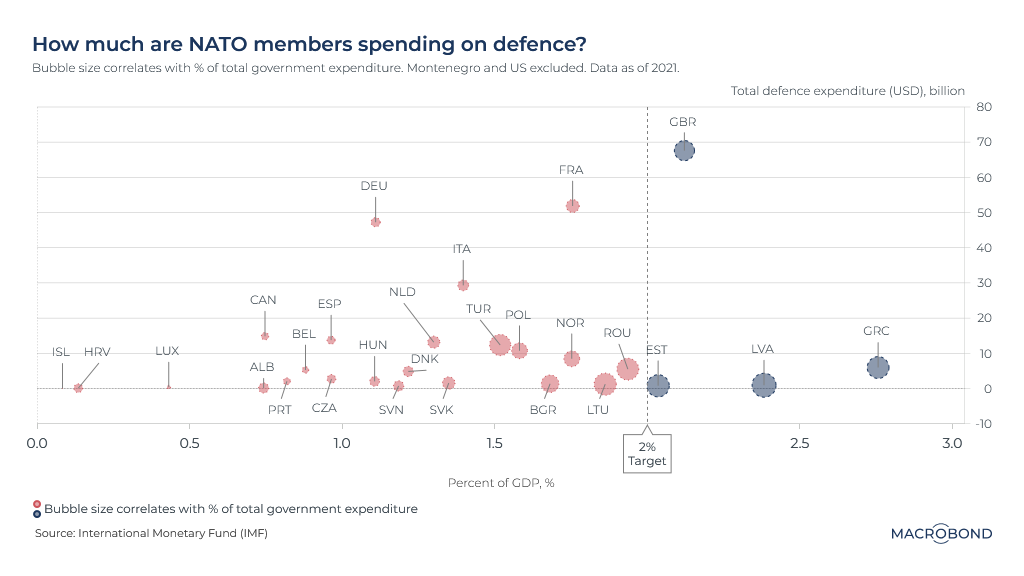

Tracking the defense spending laggards in NATO

Members of the NATO alliance meet in Lithuania in July.

As Russia’s war in Ukraine moves into its second year, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg wants member states to pledge to spend at least 2 percent of their GDP on defense.

At the end of 2021 – and as Presidents Trump and Obama both complained about – few of the non-US NATO members surpassed that 2 percent threshold, as our chart shows. (This has been changing since Russia invaded Ukraine, with nations rethinking previous stances and replenishing weapons stocks depleted by supplies to Kyiv.)

The larger the bubble on the chart, the bigger share of its budget that a nation spends on defense. Among the states that will meet Stoltenberg’s pledge, Britain’s annual military outlay dwarfs the rest in absolute terms.

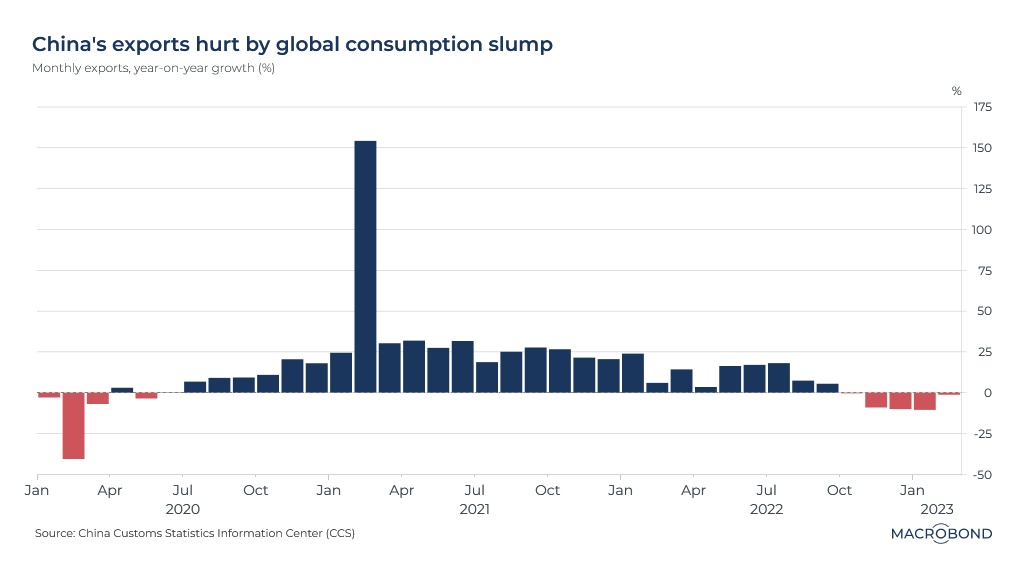

Export weakness is deflating reopening optimism in China

China might have hoped for more of a boost from reopening its economy, but that’s being thwarted by sluggish global demand for its exports.

As our chart shows, monthly exports have been falling on a year-on-year basis for five months. (To be sure, a year earlier, export growth was especially healthy amid the pandemic-driven consumption boom.)

The future of this trend will depend not just on the depth of the next recession, but trade tensions between China and the US, as some companies pursue “reshoring,” “near-shoring” and “friend-shoring” strategies that shift production out of China.

5 topics

.png)

Macrobond delivers the world’s most extensive macroeconomic & financial data alongside the tools and technologies to quickly analyse, visualise and share insights – from a single integrated platform. Our application is a single source of truth for...

Expertise

.png)

Macrobond delivers the world’s most extensive macroeconomic & financial data alongside the tools and technologies to quickly analyse, visualise and share insights – from a single integrated platform. Our application is a single source of truth for...

.png)