China's property crisis is far from over

It was sometime in mid to late 2021 when Evergrande first hit mainstream headlines. At the time, there were increasing reports that the developer was in financial trouble. The scale and size of Evergrande’s debt was alarming, at US$300 billion worth of liabilities - large enough that a collapse could trigger financial contagion, and it was becoming widely expected that a default was likely.

Ever since, comparisons between Evergrande and Lehman Brothers have been far and wide, although Chinese authorities were never going to allow a sentiment-rattling failure of the company. It just isn’t their style to let anything risk financial stability.

But the alternative has been an extremely drawn-out affair. By the time a liquidation order was handed down by a Hong Kong court last week, it had already been over two years since Evergrande first officially defaulted on its offshore debt. Subsequently, financial markets paid little attention. It was old news.

There are major questions still about how the Hong Kong-based court order would apply to assets on the mainland and doubts that offshore bondholders can recover anything at all. The order may not add much clarity for overseas investors.

It is largely symbolic of how offshore investors view China as an investment destination right now - with scepticism. But how China has dealt with Evergrande is also symbolic of how authorities have dealt with the whole property crisis. Anything that might risk financial instability is off the table, but this has often come at the expense of a potentially faster resolution to the crisis.

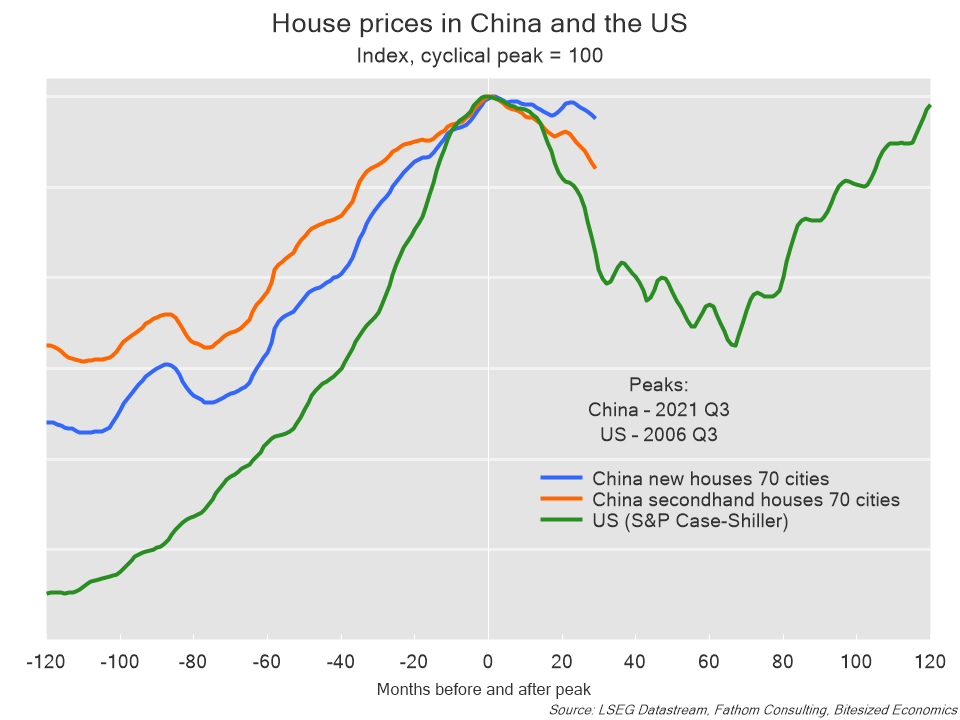

Take, for example, house price declines. Officials have previously been reluctant to allow developers to discount prices, fearing financial instability from a large fall in prices. Official data point to price declines, but new house prices are only down a mere 0.4% in the year. “Second-hand” home prices are down a larger 4% on the year, but still well below the 15-20% drops that generally characterize major housing downturns experienced in other parts of the world.

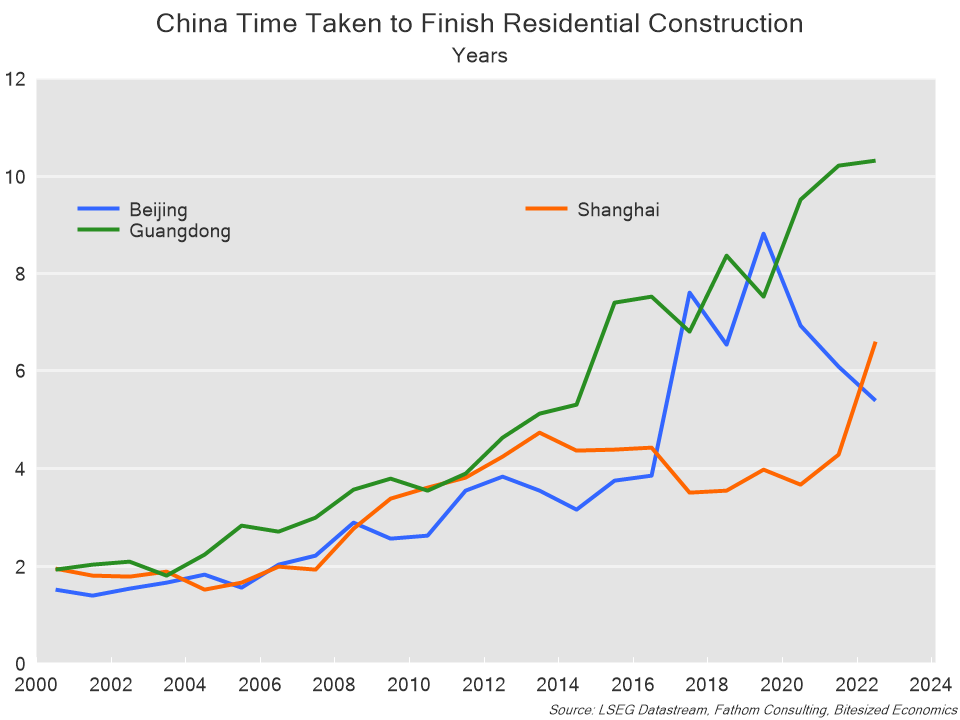

Of course, house price declines can damage consumer confidence and bring down household wealth. It could weigh further on household spending. But at the same time, the lack of price declines has prolonged the crisis. Large-scale price declines would help the market clear of excess stock, which is significant. The amount of unfinished housing equates to around six times annual sales. Estimates range from six and up to 10 years to complete unfinished stock. That’s astounding. Although not directly comparable, at the height of the US subprime crisis, unsold inventory of existing housing peaked at just over 11 months’ supply.

090224.png)

That limits the ability for the government to step in directly and finish these builds – the scale of unfinished stock is just too large, worth possibly more than US$8 trillion.

In China’s case, however, developers have needed upfront purchases from homebuyers before construction, so the large amount of unfinished apartments has locked up equity for home buyers and damaged confidence among potential new buyers.

One solution that has been proposed is to fast-track the construction of these homes. That could possibly go some way to restoring confidence among buyers. But then again, speeding up the completion of unfinished apartments would add more to the existing housing stock and possibly place further downward pressure on prices, which again, may cause financial instability. There also seems to be a reluctance to provide even larger-scale support to cash-strapped developers to complete and deliver unfinished apartments.

Consequently, rather than a financial collapse that we might have seen in other economies, China’s housing crisis has been in limbo over the past few years with no end in sight.

That being said, there have been some small signs that the crisis is progressing. There have been more reports of price declines of up to 30%, despite official data pointing to just minor falls.

Much like the liquidation order of Evergrande, these are not necessarily positive developments, but they are small steps towards an eventual resolution to the crisis. Of course, authorities have taken some other measures to support the housing market, such as gradually reducing interest rates and facilitating financing for property developers. But these do little to address the large overhang of unfinished housing or the locked-up equity of homebuyers who purchased apartments that may not be finished for years, if ever.

Moreover, the property sector is not likely to feature as prominently in President Xi Jinping’s grand vision for China. The mantra of “houses are for living in and not for speculation” still underpins the ideology of decision-making, even though it no longer features as prominently in Xi’s official speeches.

Interest rates are on a gradual incline, rather than being slashed. Developers have more favourable terms for lending, but not much of a lifeline if they have solvency concerns. As much as the government raises completing unfinished apartments as a priority, the question is by whom, particularly at a time when many developers are not in a financial position to.

So, more significant price declines and bigger lifelines for developers could lead to a quicker resolution of China’s housing crisis. But while the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) aims to shift the key drivers of the economy away from property, and at the same time, limit any risk to financial instability, the crisis is likely to continue along at a snail’s pace.

Unfortunately, it also appears that homebuyers will need to bear a big cost in this housing downturn, especially given that they have received little direct stimulus. That negative impact on household spending, as well as the drag from weaker construction, will also weigh on China’s economy for many years to come. There have been “steps” forward, but it will still take a long time for this crisis, like Evergrande’s collapse, to play out.

5 topics