Corporate and RMBS default waves arrive

In the AFR today, I write that our long-projected global default cycle has arrived. In a recent report, S&P comment that 2023 is shaping up as the worst default cycle since the GFC:

This year's global corporate default tally rose to 23 as of Feb. 28--the highest year-to-date tally since 2009--with 15 defaults in February alone, marking the highest monthly total since November 2020. Nearly three-quarters of February defaults came from U.S.-based issuers, and U.S. corporate defaults this year are already over 2.5x higher than the year-to-date 2022 total. U.S.-based media and entertainment issuers led February defaults, but the retail sector leads defaults year to date with seven (over 30% of the global tally). - We forecast the U.S. and European trailing-12-month speculative-grade corporate default rates could rise to 4% and 3.25%, respectively, by December 2023.

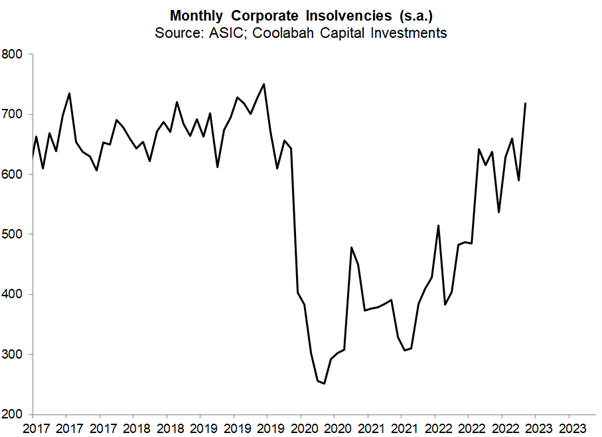

Every day we are reading about builders, developers, breweries and other businesses going bust. This gels with the data. We seasonally-adjust ASIC's corporate insolvency data, which climbed to more than 700 insolvencies in February alone relative to the pandemic lows around 200 per month. The concern would be if this trend continued...

In the AFR I note:

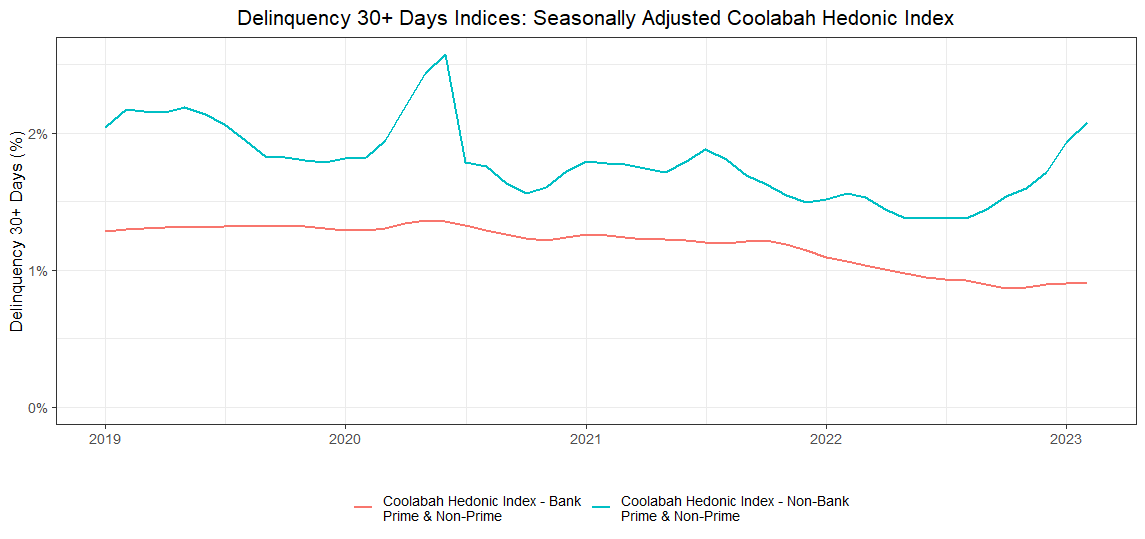

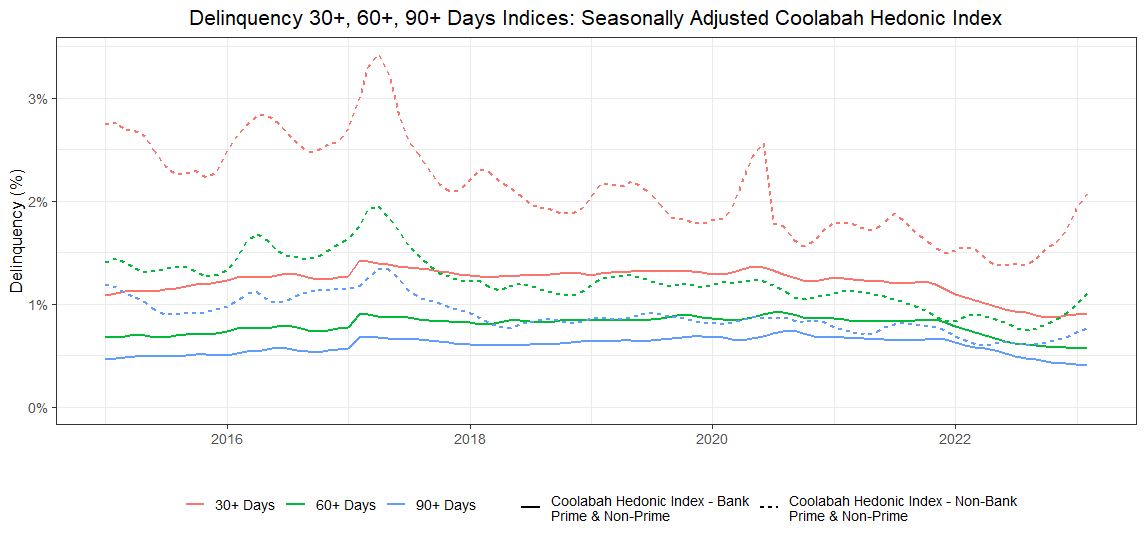

Whereas lenders can and do often hide defaults by extending and pretending (restructuring borrowers’ loans so that no formal defaults show up in the official data), the insolvency time-series does not lie. Another data source that does not lie and which we study closely is the monthly arrears reported on the circa $90 billion home loan-backed bonds, known as residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS). We compute our own compositionally adjusted arrears indices for all Aussie RMBS, which reveals a striking recent increase in the 30 days-plus arrears rate.

In the chart below, you can see our compositionally-adjusted RMBS default rates for banks compared to non-banks. Large non-bank lenders include Liberty, FirstMac, LaTrobe, Pepper, AFG, Resi and others. The first chart is just borrowers who are more than one month behind. The second chart includes the 60 and 90 days arrears rates. You can see a big difference/gap emerging between banks and non-banks' arrears rates.

Beyond the fact that non-banks normally have weaker lending standards than the banks, there is another possible explanation for this emerging gap, which I explain in the AFR:

APRA requires banks to apply a minimum interest rate buffer of 3 per cent when assessing a residential borrower’s capacity to repay a loan. Yet non-bank lenders are not subject to any of these rules. And with much higher funding costs than the banks, and a constrained ability to compete for market share, non-banks may be relaxing their lending standards to capture new clients. There have indeed been reports of non-banks reducing their interest rate buffers to as little as 1 per cent, which might be especially imprudent if central banks are required to embark on a second rate-rising cycle after the widely anticipated pause that should materialise over the next few months.

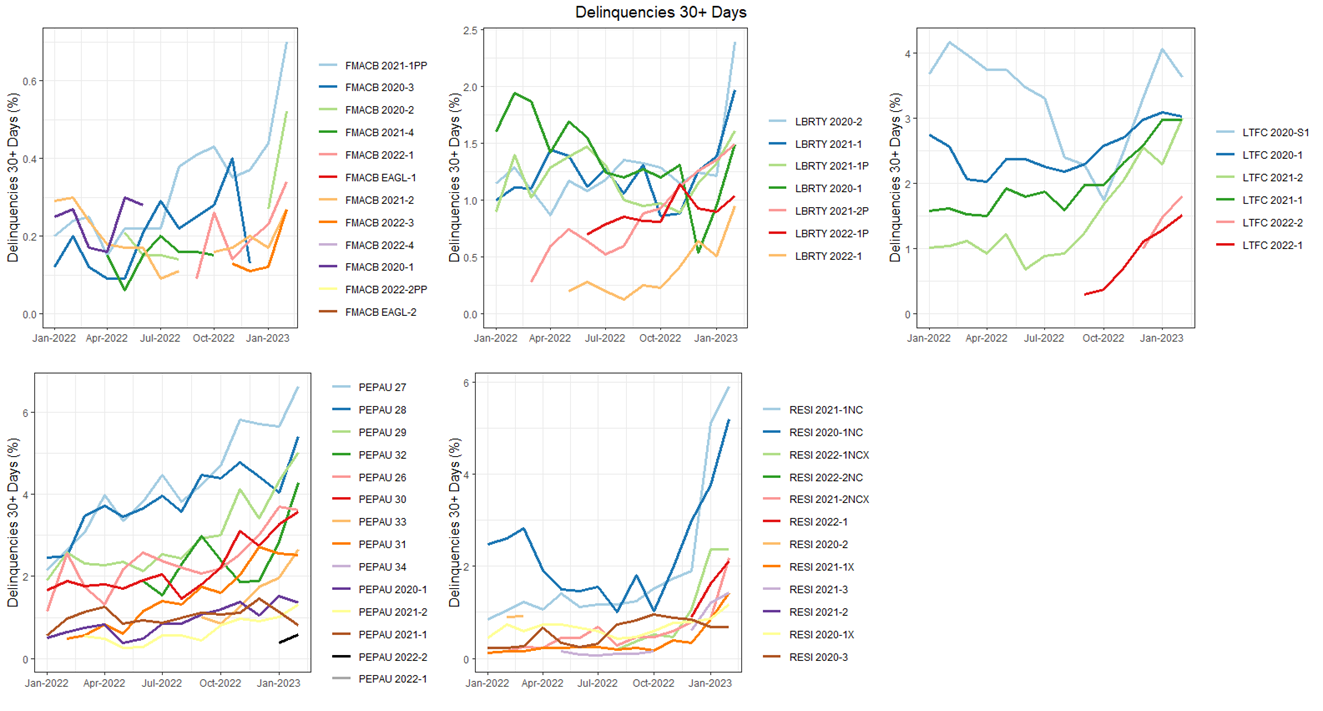

We can dive into the individual non-banks' RMBS arrears in more detail by looking at the change in their 30+ days arrears rate for different vintages of RMBS issues over time. The charts below summarise that information for FirstMac, Liberty, LaTrobe, Pepper and Resi based on data published by Bloomberg.

4 topics