Could Donald Trump’s ‘endgame’ be global debt forgiveness?

Donald Trump has injected a high level of uncertainty into the global economy with the move to redefine global trade relationships. Yet the approach taken appears counterintuitive if the aim is to achieve a negotiated outcome which is more favourable to the US based on lower global tariffs. Yet lower tariffs may not be the end game that is being aimed for but rather global debt forgiveness.

Are Announced Tariffs the ‘End Game’ or the Starting Point for Negotiations?

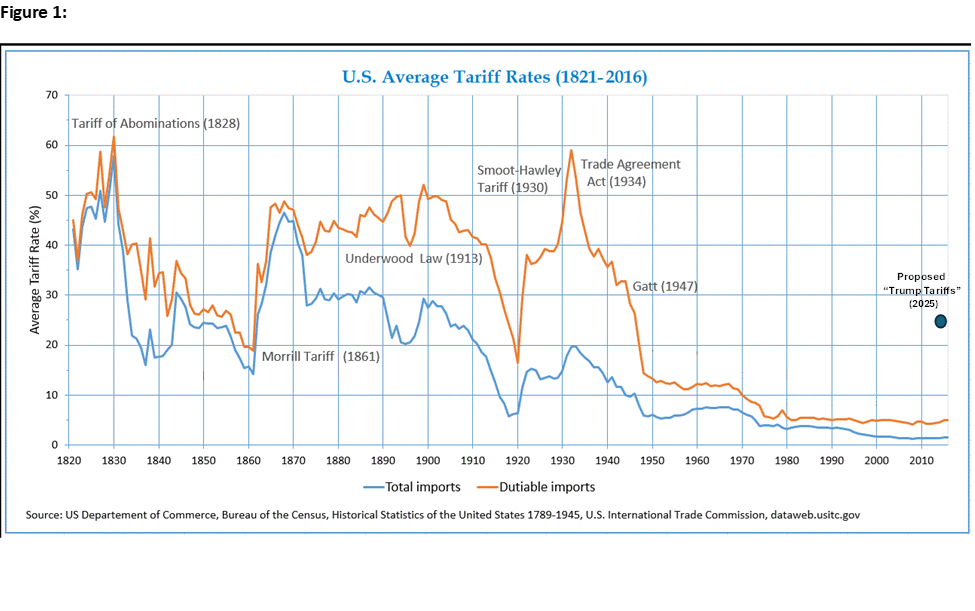

On ‘Liberation Day’ the Trump Administration (‘Administration’) announced a sweeping increase in tariffs to be applied to virtually all countries. This change in policy has taken the potential tariff rate applied in the US from 2.2% in 2023 to an average of around 25% which is the highest level since the 1930’s (See Figure 1).

The initial question is whether the announced tariffs are the ‘endgame’ or simply the start of a negotiation process which will end in the average tariff applied being closer to the 10% minimum? Here the message from the Administration has been somewhat confused with differing explanations and pronouncements which have only muddied the water. To illustrate the confusion the following is coverage of statements post Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ announcement :

[To highlight the state of communications White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told CNN that Wall Street should “trust President Trump” and that no level of negotiation by other countries would reduce or eliminate the outlined plan before the tariffs go into effect.

“The president made it clear yesterday this is not a negotiation, this is a national emergency,” she said.

White House talking points obtained by NBC News also emphasized that the tariffs were not a negotiating tool.

The message about “not a negotiation,” however, has been contradicted by Trump’s own economic advisers — who insist the move is part of a negotiating ploy to bring back what they call “fair trade” — as well as his own family and even Trump himself.

"The tariffs give us great power to negotiate. Always have," Trump told reporters Thursday on Air Force One.

Trump’s son Eric posted on X: “I wouldn’t want to be the last country that tries to negotiate a trade deal with @realDonaldTrump. The first to negotiate will win — the last will absolutely lose. I have seen this movie my entire life…”

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick also told Fox News host Sean Hannity that the tariffs would prompt negotiations by foreign trade partners.

“I’ve got to imagine that a lot of these countries are not going to like the tariffs that go into effect tonight at midnight, and they are going to want to negotiate,” he said. “You think I’m wrong?”

Source : ABC News]

So while the waters are muddied it appears likely that the Administration is open to negotiations.

What are they Negotiating?

This raises the simple question of ‘If the US is open to negotiations what is being negotiated?’. It is tempting to say that the answer is obvious : What is being negotiated is the level of tariffs applied by other countries to US imports. But there are some complications around such an interpretation. To better understand the issues it is important to consider how the reciprocal tariffs are being calculated by the Administration. The reciprocal tariffs are not being calculated based on actual tariffs applied by other countries. Rather when the Administration refers to tariffs they are referring to ‘effective tariff rates’ which other countries are supposedly imposing on the importation of goods from the US. Unlike tariffs, effective tariff rates are meant to capture a combination of tariffs and other non-tariff trade barriers (such as biosecurity measures, quotas, and inspections) and currency manipulation. The reciprocal tariffs then are the tariff rates the Trump administration will apply to imports on goods from those countries, in retaliation, to try to level the trade playing field.

The first issue is how the ‘effective tariff rate’ is being calculated given that quantifying the impacts of non-tariff barriers and currency manipulation are highly problematic. To quantify these impacts the Administration appears to have made the simplifying assumption that any trade deficit must be the by product of tariffs and other non-tariff trade barriers (such as biosecurity measures, quotas, and inspections) and currency manipulation. Accordingly, the size of the trade deficit for each country is divided by the value of imports to derive the ‘effective tariff’ rate. For example the US has a total trade deficit with China of approx. $295bn which is divided by total US exports to China of $438bn to get to an effective tariff rate of 67%.

To this calculation is applied an ‘across the board’ minimum tariff rate of 10% so even countries with a trade deficit to the US, such as Australia, are hit with a 10% tariff rate. In effect any resulting negotiations around the ‘effective tariff rate’ does not involve ‘horse trading’ around actual tariffs but rather targeted a trade deficit outcome. The issue is that there are a broad range of factors which determine trade deficits between countries only some of which will be directly under the control of the government. Indeed, the trade deficit that the US has with other countries can often be impacted by policy decisions within the US itself. This makes not only entering bilateral negotiations but also policing such agreements versus specific targets highly problematic.

The second issue facing any attempt at negotiation is that the focus on trade deficits means that there is effectively a separate reciprocal tariff rate calculated for each country. Accordingly, negotiations would need to be undertaken on a bilateral basis between the US and each country. This is clearly a time consuming process involving around 90 countries.

Thirdly, it is clearly preferable to be able to negotiate on a global level so that a single quantifiable global outcome can be achieved. Not only does this make negotiation simpler but is also makes policing of the agreement easier as there are clearer outcomes under the control of the relevant parties. An example would be the Plaza Accord in 1985 where France, West Germany, Japan and the US agreed to depreciate the USD relative to the Japanese Yen and German Deutschmark. Here there were a small number of players and a clearly quantifiable outcome to measure success against. This type of discipline is likely to be missing with any agreements associated with the concept of targeting trade deficit outcomes across nearly 90 countries.

Could the desired outcome be debt forgiveness?

Given how difficult it would be to establish and police negotiated outcomes around the Administration’s calculation of effective tariffs what alternative offer could the rest of the world bring to the table to access the minimum tariff rate of 10%? The answer could be ‘debt forgiveness’. Debt forgiveness is the complete cancellation of a portion or all of the debt owned by a country to its creditors often in exchange for certain conditions such as policy reform etc. Normally debt forgiveness is associated with developing countries but there is no reason why it couldn’t be applied to a large developed country such as the US.

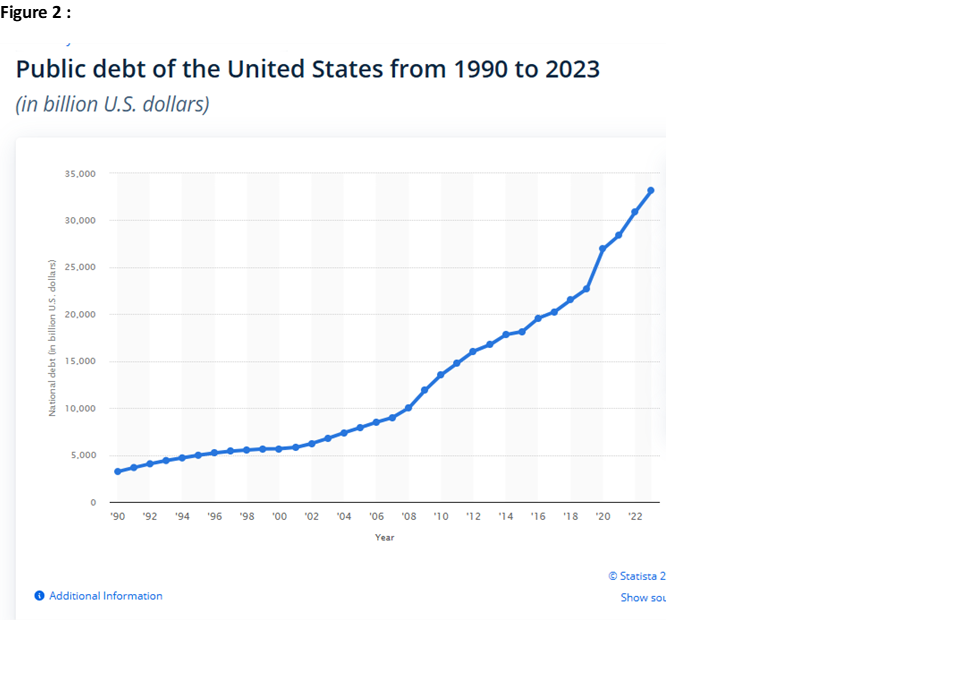

To see why a policy outcome involving debt forgiveness could be attractive to the Administration consider that as at March 2025 the total public debt was over $36trn with around 1/3 held by foreigners. With debt levels at the highest level in history there is the added problem that around 15% of the Federal budget goes in interest servicing costs (see Figure 2).

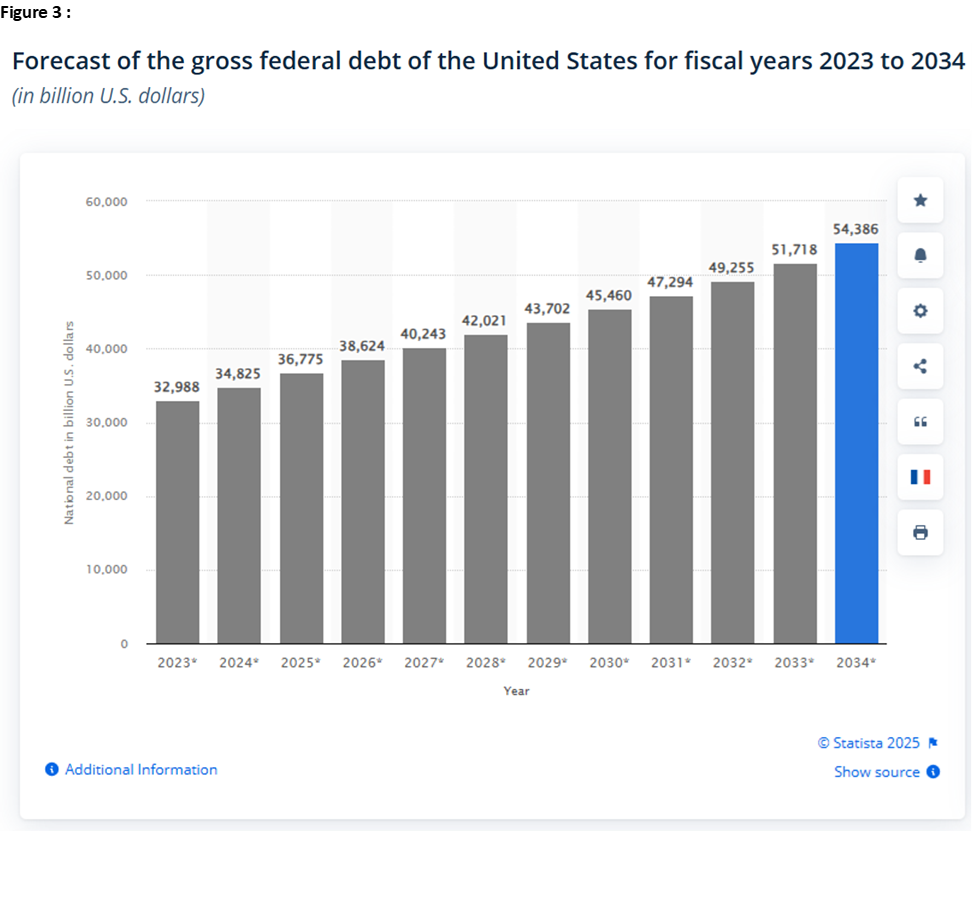

More worryingly not only has total public debt risen dramatically over the last decade but is also forecast to continue growing at a material rate over the next decade (see Figure 3).

It is not an exaggeration to say that given these debt dynamics there is little prospect that the US can stabilise, let alone repay, this much debt in the absence of material (a) cuts in government expenditure, (b) increases in taxation and/or (c) debt forgiveness. Of the three options available debt forgiveness has the added advantage that it can be selectively applied to foreign debt holders thereby limiting domestic political blowback. This points to one option for countries faced with high tariffs being to negotiate a debt forgiveness plan for the US

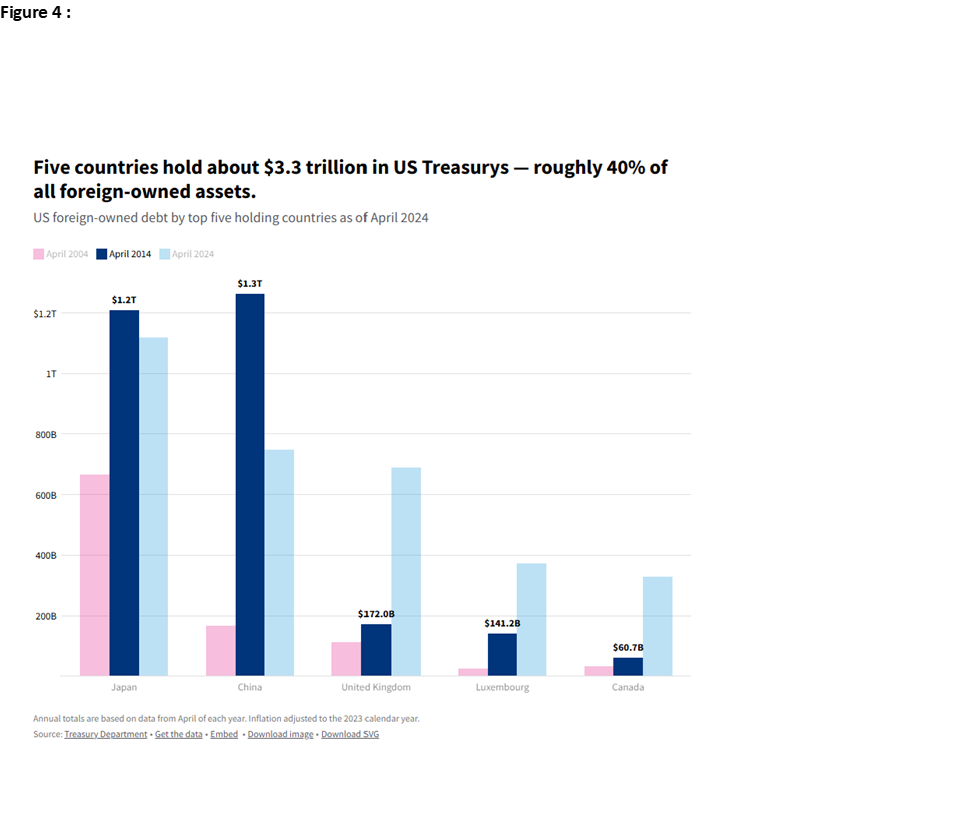

Debt forgiveness as a means for countries being able to globally ‘buy their way’ into the minimum 10% tariff rate has several advantages from a negotiation perspective. Firstly, it means that a single global deal can be struck reducing the need for large numbers of bilateral negotiations. Secondly, as the cost will be borne by foreign governments a clear target and outcome can be set by both parties. Thirdly, around 40% of foreign US debt is owned by only five major countries with the two largest holders (China and Japan) already in the Administration’s sights regarding what it views as ‘unfair trade’ practices (see Figure 4). Finally, it sets out the prospect of a clear and tangible path to a nearer term resolution which the Administration can point to as a victory.

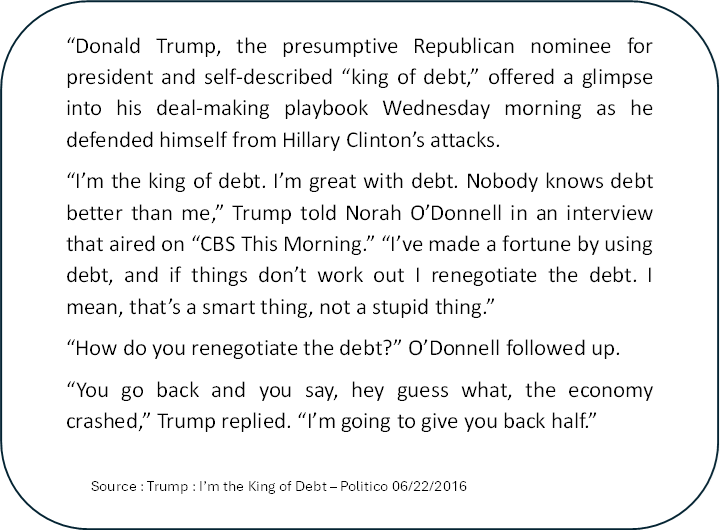

Yet it must be recognised that the very idea that the Administration would leverage reciprocal tariffs to force an agreement on global debt forgiveness does seem extremely farfetched. After all, how could the leader of a country which has been the architect of the post war economic and financial system even consider such a strategy? Well as it turns out Donald Trump may have hinted at such a strategy as this interview in 2016 highlights :

Forcing foreign holders of US government bond holders to forgive a material portion, if not all, of the US government debt they hold as the price for accessing a 10% tariff rate has clear negative implications for the US and its ability to access bond markets going forward as well as the USD as a reserve currency. Yet history shows that markets can have short memories with respect to dealing with debt restructurings by national governments. This raises the prospect that debt forgiveness may be one of the outcomes the Administration is either aiming for or will accept as the price of foreign countries being allowed access to the largest consumer market in the world. Unfortunately, whether negotiations are around effective tariff rates or debt forgiveness, the main impediment remains whether the requisite level of trust exists between the Administration and the rest of the world to reach any form of negotiated outcome.

2 topics