Cycle is not a dirty word

In a perfect world, every stock we own would be net cash, generate high returns, be run by a world-class management team, and cheap. In practice, the presence of the first three criteria usually means that the investment falls over at the last criterion. Just like we don’t tend to stumble across $500k houses in Point Piper with Sydney Harbour views, the stock market is rational: it usually bids the best businesses up to the highest price. This means we usually have to compromise on something. The one thing we never compromise on is the balance sheet – a business must have the appropriate financial structure for its business model or else we equity investors may find out exactly where we rank in the capital stack! Assuming the balance sheet is appropriate, we rely on our judgement as investors to juggle the trade-offs between business quality, management quality and valuation.

One hunting ground where we tend to find businesses with attractive valuations is when everyone is very worried about “the cycle”.

For example, with a consensus view that a recession looks likely in the US, Europe and potentially Australia, we are seeing opportunities in businesses that are leveraged to the building cycle.

The first thing to figure out when sifting through these ideas is whether the business sells a commodity. In investing it pays to have an open mind: cyclical businesses that sell commodity products can be great investments; one need look no further than BHP (ASX: BHP) to find such an example. However, we have a few requirements. Firstly, we want to see a pristine, (preferably net cash) balance sheet. Returns are outside the company’s control – typically dictated by the level of demand for a commodity and hence the price. Financial leverage combined with operating leverage can mean lights out.

Second, we look for evidence of good industry structure. This means as few players as possible. Very few things are “pure” commodities. Often there are hidden barriers to entry – start-up costs, distribution networks or captured supply chains – that keep industries rational and cosy. This seems particularly prevalent in Australia. The tyranny of distance, both from global supply chains and having a small population spread across a large country, means a fixed profit pool that often doesn’t support a third or fourth entrant. Two or three rational market players can see everyone making OK returns on their capital.

Finally, we want a compelling valuation. If there’s no intangible franchise value in a business, if it just makes bog-average products, you don’t want to pay a high price for it.

Luckily, the tendency for investors to tie themselves in knots trying to forecast where we are in a cycle tends to throw off frequent opportunities to buy cyclical businesses at good prices.

Unluckily, those opportunities usually only come around when the cycle looks particularly on the nose. As such, we find you have to be brave and also be prepared to be early (potentially very early!), and willing to add to a position if it continues to fall as the cycle deteriorates. The risk in investing in cyclical commodity businesses is that, as Howard Marks says, to be too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong. It is for this reason that we rarely make these initial investments our largest positions, preferring a smaller position size that we can add to should the leading indicators deteriorate further.

One business we feel ticks these boxes is CSR (ASX: CSR), a recent addition to the portfolio. The company manufactures and distributes plasterboard, aerated concrete, bricks, fibre cement, insulation and other products under a range of different brands. CSR also has a 25% effective interest in the Tomago aluminium smelter in Newcastle.

We are under no illusions as to the underlying quality of this business. With perhaps the exception of aerated concrete, where CSR has exclusive rights to the Hebel brand, the bulk of what CSR makes, and sells are commodity products. Returns will be cyclical, dominated by the level of residential building activity in Australia. Our thesis in owning CSR is that (a) the value of the surplus property underpins the bulk of the valuation, such that we aren’t paying a very high residual price for the building products business, and (b) this building products business is probably a shade higher quality than it has been historically; mid-cycle margins and returns for CSR’s building products should be higher this decade than the prior decade due to improving industry structure.

Throwing in a rock-solid balance sheet ($142m net cash) makes the investment proposition stack up for us, albeit this is not without risks. Our valuation is based on our assessment of mid-cycle EBIT; however, we will be wrong on this assessment if industry rationality breaks down as demand falls (that is, if we see evidence of price-cutting to chase market share).

Building products business: average quality but industry structure has improved

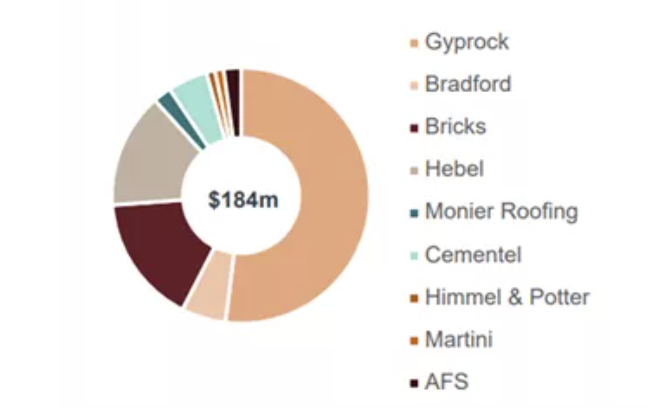

From an earnings perspective, the three most important businesses in CSR’s Building Products portfolio are plasterboard (Gyprock), Bricks and Hebel (aerated concrete), making up a combined c75% of EBIT.

CSR has a dominant market share position in each of the plasterboard, brick and aerated concrete markets as a function of recent industry consolidation (Gyprock, PGH Bricks) and product exclusivity (Hebel).

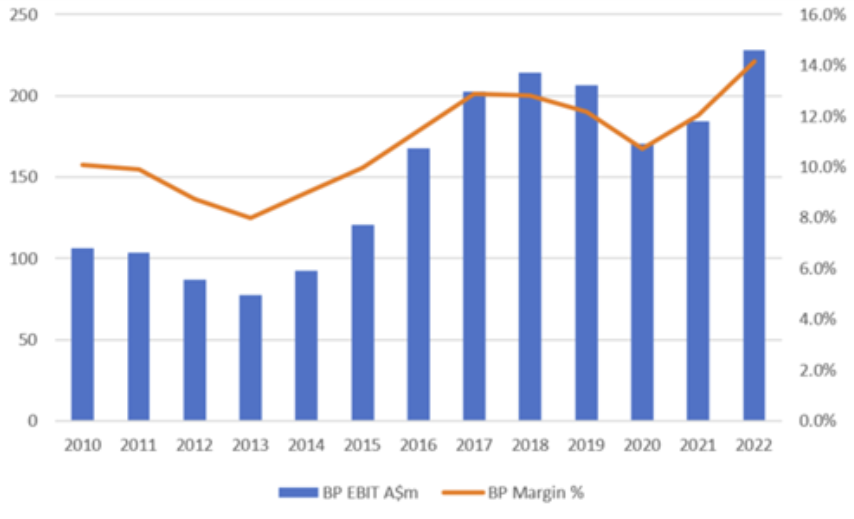

As per the below chart, EBIT margins are highly cyclical: in a great year (like FY23F) CSR is on track to make a 14% EBIT margin; in a bad year (2013) it made only 8% EBIT margins. We believe a return to these lows is unlikely for reasons we step through below. As such, we forecast trough EBIT margins of 10% rather than a historic 8%, and mid-cycle EBIT margins of 12% rather than a historic 10%.

Source: Company data, Airlie research.

Plasterboard is the most important business, accounting for over 50% of the building products’ EBIT. East-coast plasterboard is a three-player market, with CSR and Knauf enjoying c35-40% market share each, and ETEX 20%-30%. Boral (ASX: BLD) used to be the main player against which CSR competed; however, Knauf recently effectively bought Boral out of its local assets in 2021. Boral historically had a reputation as the competitor you didn’t want in any market, as it leant heavily on price to chase market share during downturns. This weighs on returns for all players. We view the exit of Boral from plasterboard as a net positive for industry rationality. While plasterboard is undoubtedly a cyclical business, our discussion with industry participants suggests plasterboard is at the lower end of cyclicality – the plasterboard cost base is fairly variable as you can pull shifts off when demand declines, protecting EBIT margins. We believe EBIT margins vary by only a few percentage points through the cycle.

The main driver of our assumption that CSR is unlikely to retest its prior EBIT margin lows is the improved industry structure in bricks. The Australian bricks market has gone from a three-player market to two after CSR bought Boral out of their joint venture in late 2016.

A bricks business has a huge fixed-cost base; a brick kiln runs 24/7, so it’s hard to pull costs out in a downturn. Conversations with industry participants suggested CSR’s bricks business was breakeven at best during the prior housing downturn of 2010-2013. Management is also proactively managing the asset base to recycle unrequired brick sites into the property portfolio for alternative uses. For example, CSR were able to close a brick manufacturing site at Darra in Queensland and push the capacity through an upgrade at their NSW site in Oxley, freeing up the Darra land to be redeveloped and sold. We estimate Darra could generate over $100m in EBIT for the business over several years via the sale of subdivided land. This network optimisation reduces the risk that high-fixed-cost brick plants will swing to EBIT or cash loss-making at the bottom of the cycle.

These improvements in industry structure lead us to an estimate of mid-cycle EBIT for building products of c$200m. (Note the building products business is on track for >$250m EBIT this year.) Deducting the full corporate costs of c$25m from this division gives mid-cycle group EBIT of $175m ex-aluminium.

Property underpins 65% of market capitalisation

CSR’s property division looks to maximise financial returns of surplus former manufacturing sites and industrial land. The bulk of the value of this division was a ‘gift from the gods’: in what was surely one of the most sizeable value transfers in recent Australian corporate history, CSR was able to acquire Boral’s 40% interest in its brick JV for $126m in 2016. Extraordinarily, this included 12 manufacturing operations and mothballed sites, including the aforementioned Darra site, as well as 140ha of developable land at Badgerys Creek in Western Sydney.

This is valuable land, located on the southern boundary of the future Western Sydney Airport. CSR recently sold a small parcel of this land at $4.5m/ha, implying the remaining site could be worth >$600m. Cheers, Boral!

This episode is another reminder of why we put a huge emphasis on the quality of a management team. It’s not always around the value creation they can achieve, but also avoiding the significant value destruction that can occur if a business is poorly run.

CSR have had their total “as is” property book independently valued at $1.5bn ($1.1bn for 450ha of Western Sydney property, and $400m for additional freehold properties), which compares to a market capitalisation of $2.3bn. While this value will be realised over the long term via redevelopment and sale of surplus land, this implies a residual value for the business of c$800m, which is cheap when set against our estimate of mid-cycle EBIT of $175m (4.5x EBIT). We note peer Fletcher Building currently trades on just under 8x arguably peak-cycle EBIT. This also ignores any earnings from aluminium.

To us, CSR is not a particularly high-quality business, and the cycle is clearly unsupportive from here. However, we believe there has been an improvement in the quality of the business as a result of favourable industry consolidation, and see compelling value in the combination of OK assets, solid property underpinning, and a net cash balance sheet that provides optionality through a downturn.

Learn more

Airlie seeks to identify Australian companies based on their financial strength, attractive durable business characteristics and the quality of their management teams.

2 topics

4 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned