Dark clouds ahead: The rising risk of a US recession

Historical Context and Initial Observations

For our purposes, we take up the history of events from around two years ago. In late 2022, the US economy was rapidly slowing with nominal consumer spending growth dropping to around 3% year-over-year (y/y). Interest rates in the US had not yet peaked. Extrapolating this decline in spending, a recession forecast seemed reasonable. Nominal spending growth had plummeted from about 20% at its post-Covid peak to just 3% by late 2022.

However, a recession or outright decline in nominal spending was not imminent. Instead of continuing to decline, spending stabilised. Why? The Covid-19 pandemic forced people to stay home, and combined with massive fiscal transfers, households paid off significant credit card debt and built up larger-than-normal savings. These buffers allowed households to stabilise their spending.

This meant that, two years ago, McDonald’s could grow revenues by around 9.7% y/y, Starbucks by 12% y/y in North America and Mondelez (owner of Cadbury, Oreo, Toblerone among other brands) by 13% y/y. However, changes have since made their way through the system. Today, McDonald’s is reporting a decline in nominal revenue growth of around -1% y/y, Starbucks by -2% y/y and Mondelez by -3.5% y/y. Did Americans suddenly fall out of love with burgers, coffee and chocolate?

What we’re starting to see is a significant segment of the population experiencing a decline in their spending power. This effect has taken its time to manifest. Initially, it was the least well-off that bore the brunt of the rising cost of living. But now there is a large enough segment of the population feeling the impact of high interest rates that the revenues of large corporations are being impacted. A material segment of the population has run out of savings and credit card debt to support spending power. It’s clear that high interest rates in the US is continuing to curtail savings and spending power.

The Labour Market is Key

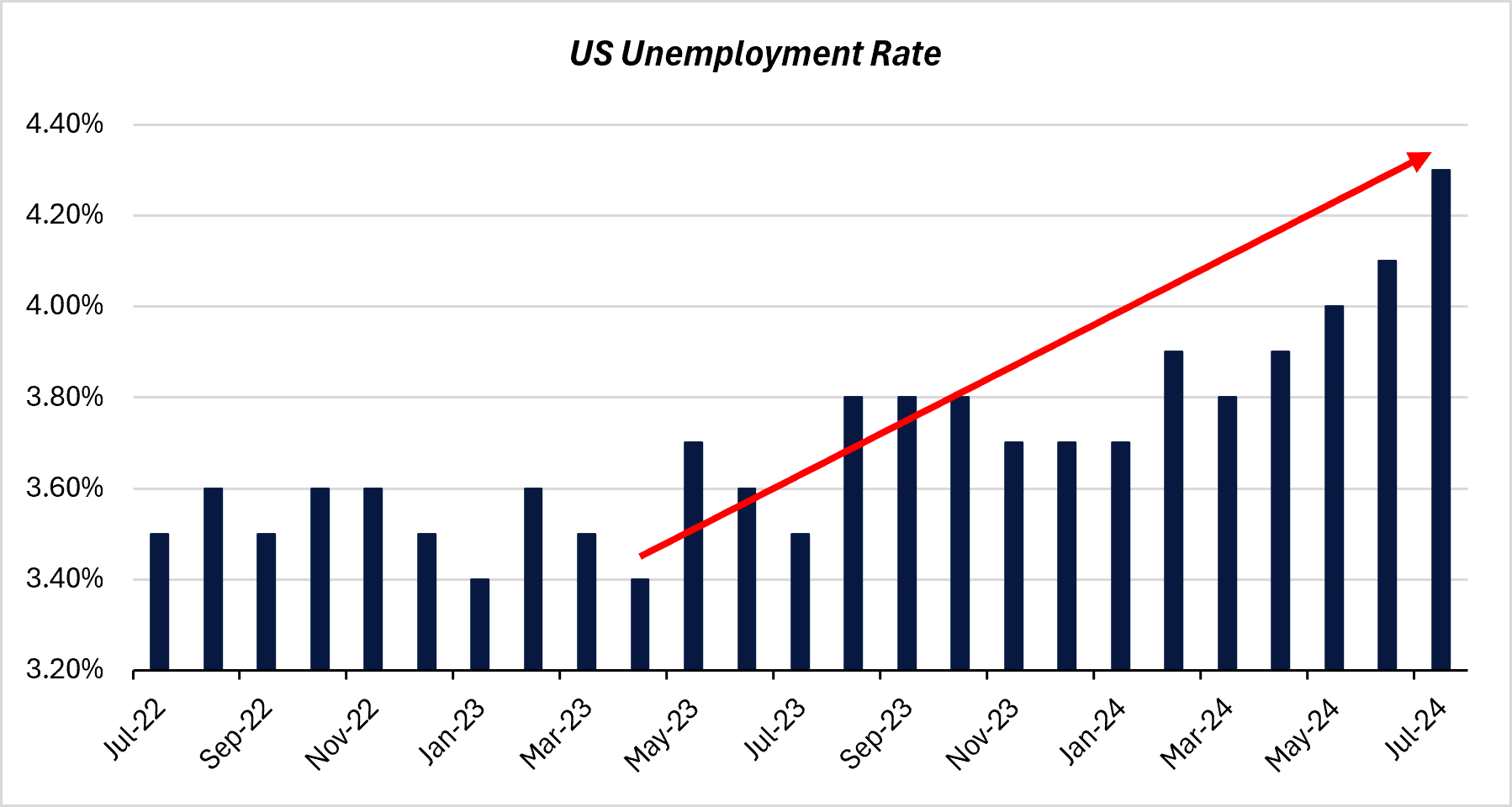

It’s developments in the US labour market that matter most in determining whether we end up in recession or not. We are beginning to see some troubling indicators, with the most concerning being the rise in the unemployment rate:

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

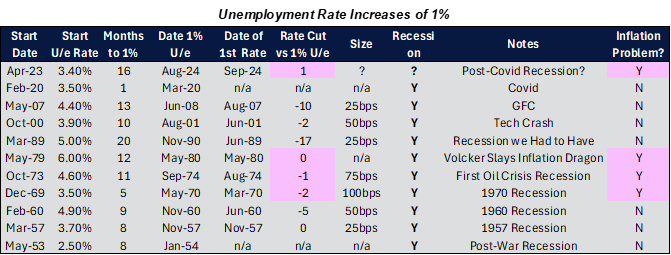

Why worry? The reason is because, historically, every time we’ve seen a rise in the unemployment rate of about 1%, a recession has followed. The table below illustrates how events transpired each time the unemployment rate increased by 1% since the end of World War II:

The US economy has experienced a recession 10 out of 10 times when the unemployment rate has risen by 1%.

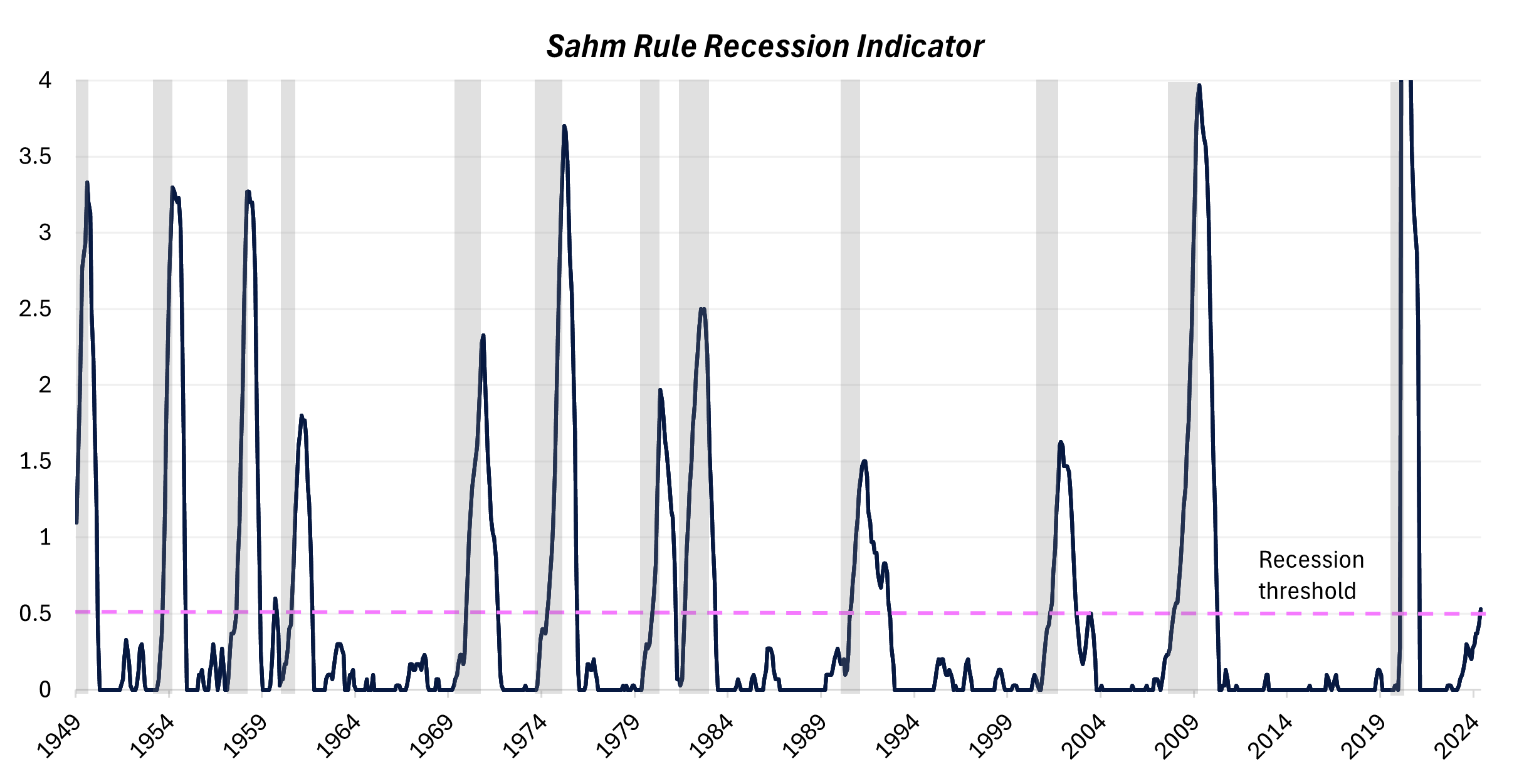

We’ve consistently maintained that the key to determining whether we face a recession lies in the stability of the labour market. The difference between a soft landing and a hard one hinges on what happens to jobs. In the chart below, we can see that we’re already at the recession threshold based on the Sahm rule, which indicates a recession has started when the three-month moving average of the US unemployment rate is 0.5 percentage points or more above its lowest during the previous 12 months.

Fed rate cuts take their time to work through the system, much like how rate hikes took a significant amount of time to curtail inflation. In this cycle, the Fed has been relatively slow at cutting the cash rate relative to when the unemployment rate had risen 1% from its nadir. This delay is partly due to post-Covid inflation. As the pink highlighted rows in the table above indicate, when inflation is a concern, the Fed tends not to cut interest rates too pre-emptively.

Will History Repeat?

Will this time be different? After all, this economic cycle has behaved differently to before. We’ll be looking for signs that the US consumer may respond more vigorously to rate cuts than previously. But we’re cognisant that a large segment of the population has run out of savings and credit card juice. In other words, there’s now a lot of forced savers.

Higher income earners have more spending power in reserve, but will they spend it? As the adage goes, one can lead a horse to water, but will it drink? For the first time since the start of the economic recovery, we’re starting to see weakness in spending on airlines in Europe and the US. But we’re not seeing it in cruise lines. We’re seeing material weakness at McDonald’s, Starbucks and Mondelez, but we’re seeing reasonable results at Chipotle, Procter & Gamble and Coca-Cola. We’re seeing weakness at Visa but less so at Mastercard. We’re seeing another bout of weakness in the US housing sector. What’s clear is the direction of travel as the impact of interest rates continues to work its way through the economy. The picture was less mixed 2 years ago.

And while Big Tech is still going to spend on capex and mega projects are underway as a result of US fiscal policy, the size of these increases are likely small (though not insignificant) relative to a potential decline in US consumer spending.

Stock Market Dynamics and Consumer Spending

Consumer behaviour might be influenced by the direction of the stock market. During the tech crash, consumer spending power was closely tied to changes in the value of collateral. Could we see a similar scenario unfold again?

There are several recent developments that give us pause when thinking about where the stock market may go:

- The latest generation of NVIDIA Blackwell GPU chips have design flaws. The new Chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS-L) technology used to make them has been shown to cause warpage. On top of this, TSMC doesn’t have enough CoWoS-L capacity to ramp production of Blackwell chips at pace. TSMC plans to convert an existing CoWoS-S plant into a CoWoS-L plant, which will take time. Overall, these developments cause SemiAnalysis, a semiconductor research specialist, to conclude that “this setback [will impact NVIDIA’s] production targets for Q3/Q4 2024 as well as the first half of next year.” While the forthcoming quarter may look OK, sales growth is likely to slow.

- Under the political cover of a US election, Israel seems to be asking for a war with Iran. The skirmishes on the northern border already made for an untenable situation, and Israel’s leadership has made a decision to enforce change by confronting Iran. Now that the operations in Gaza are basically complete, Israel can pivot its army to fighting Hezbollah and Iran. Israel made its intentions clear by assassinating high-level Hamas leadership on Iranian soil. The last time high-level Iranian leadership was assassinated was when President Trump assassinated Soleimani in Baghdad. According to Australian military commanders, this event changed Iran’s strategic dynamic in the Middle East. Iran, who had previously worked with the US to fight the ISIS threat, became hostile. When Israel recently hit Iran with missiles, the Iranian leadership covered it up. This time, though, there was no cover-up of the assassination.

- We will publish a note on Japan in due course, but the recent policy change from the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is likely to lead to large amounts of foreign asset selling from Japanese pension funds and insurance companies. Initially under Prime Minister Abe, the Japanese have pursued policies that encouraged the outflow of capital to weaken the currency and kick-start the economy. Like trying to start an old lawn-mower in the dead of winter, it wasn’t until this year that Japan achieved what looks like escape velocity. Combined with a weak currency that became threatening to Prime Minister Kishida’s power, the BoJ has engineered a major pivot. This pivot is likely to force the Japanese to sell stocks and the US dollar in significant volumes.

- Warren Buffett has been selling Apple and other stocks in earnest. His Q2 sales of stocks represented the fastest rate of sales for Berkshire Hathaway ever.

A dent in the trajectory of AI growth against sky-high expectations, a possible broader war in the Middle East to improve Netanyahu’s forthcoming election pitch and a Japanese policy pivot is likely to pressure the stock market. A weaker stock market could weaken consumer spending.

Concluding Thoughts

In our judgment, the odds of a recession in the US are better than even. We’re on the close lookout, however, for signs that this time might, once again, be different. If a recession were to come to pass, it would likely be a slow one. The 2000 dotcom crash, notably though, occurred during a slow-rolling recession.

4 topics