Do you want to be a ‘first mover’ in the Australian ‘build to rent’ market?

The current perception is that Australia is in the grip of a housing crisis, hit by rising rents and falling vacancy rates. ‘Built-to-Rent’, a form of rental housing relatively new to Australia, is seen by many as part of the solution to the ‘housing crisis’. Indeed, several research reports have indicated that with the right support build-to-rent housing could result in an additional 150,000 homes over the next 10 years. Such potential growth will likely result in a material increase in investor interest in the sector. But what is ‘build to rent’ and how is it likely to be applied in Australia?

What is Build to Rent?

Build to Rent (‘BtR’), though more established in the UK and USA, is a relatively new model for urban housing development in Australia. BtR apartment complexes are designed and constructed by a developer who retains ownership of the building when it’s complete. The apartments are then rented out to tenants by the developer, which also manages and maintains the complex. The funding for such developments is sometimes backed by an institutional investor such as a superannuation fund. The BtR model stands in contrast to the Build to Own (‘BtO’) model. The BtO model is where a property developer will build an apartment complex and then sell the units off to individuals, who will either choose to live in them or rent them out as investment properties.

Types of Business Models

Within the BtR market there are a range of business models which developers may adopt. Accordingly, there may be multiple ways for investors to access the market which may in turn alter not only realised returns but the nature of those returns in terms of composition between income and capital gains. The two most common business models investors are likely to come across are :

Firstly, where the focus is solely on the rents yielded over the life of the building. The rental yield-only BtR business model is relatively circumscribed and specific to where the land is only leased with the BtR developer-operator obliged to hand the asset over to the landowner at lease expiry. This model is already used by not-for-profit housing providers in the development of affordable rental housing (including with a mix of market-rent and below-market apartments) as well as on-campus student accommodation This model is akin to a ‘pure infrastructure investment’ with development viability entirely dependent on operating revenues over the term of the lease.

Secondly, where the property is managed to generate both rental returns and capital gains from long-term rental use. Such a model aims to earn increases in capital values but only from the growth in rental income. In some ways the business model is similar to that of a ‘pure infrastructure investment’. The major difference being that investors will be more exposed to the broader economic impacts on rents and capital values given the acceptance of leasing risk by the developer operator. As this business model is the one investors are more likely to come across the rest of the paper assumes this to be the default model.

Two other business models are worth highlighting though both are best considered as hybrids in terms of gaining exposures to BtR. One is the ‘build to sell later’ model where rental returns are uncompetitive over the long-term. Under such a model the interim rental income earned is less significant compared to the expected increase in capital value on the eventual disposal of the underlying apartments. For such developments the ability of the buildings to be capable of strata subdivision becomes important to ensure an exit strategy to realise any increases in capital values.

The other hybrid model is that of mixed-use developments. With a mixed-use model the developer- operator makes use of ‘air rights’ over a commercial property to incorporate BtR thereby increasing the return on the overall property development. An example of this would be the introduction of a residential component above a shopping centre. The incorporation in BtR becomes particularly attractive in such a situation for a couple of reasons. Firstly, as the valuations assigned to existing commercial sites do not reflect the potential for residential development in the airspace above, BtR becomes a way to add value to developments. Secondly, BtR as a model is particularly attractive when combined with commercial assets as it does not compromise control of the whole property as a strata-subdivided residential component would. Mixing BtR with retail and other commercial developments is accordingly another approach to providing BtR solutions.

Why is Build to Rent on the Radar Screens of Investors?

Traditionally institutional support for residential housing has been limited and where it has occurred the focus has been upon specific types of projects such as student accommodation. One of the key drivers for this has been historical tax policies, such as negative gearing, which have compressed residential yields in Australia making the residential sector unfavourable to institutional investors relative to other segments of the commercial real estate market. Such biases have resulted in relatively low yields, and a market and taxation structure that favours capital gains. The result has been a bias towards BtO rather than BtR as the preferred institutional business model.

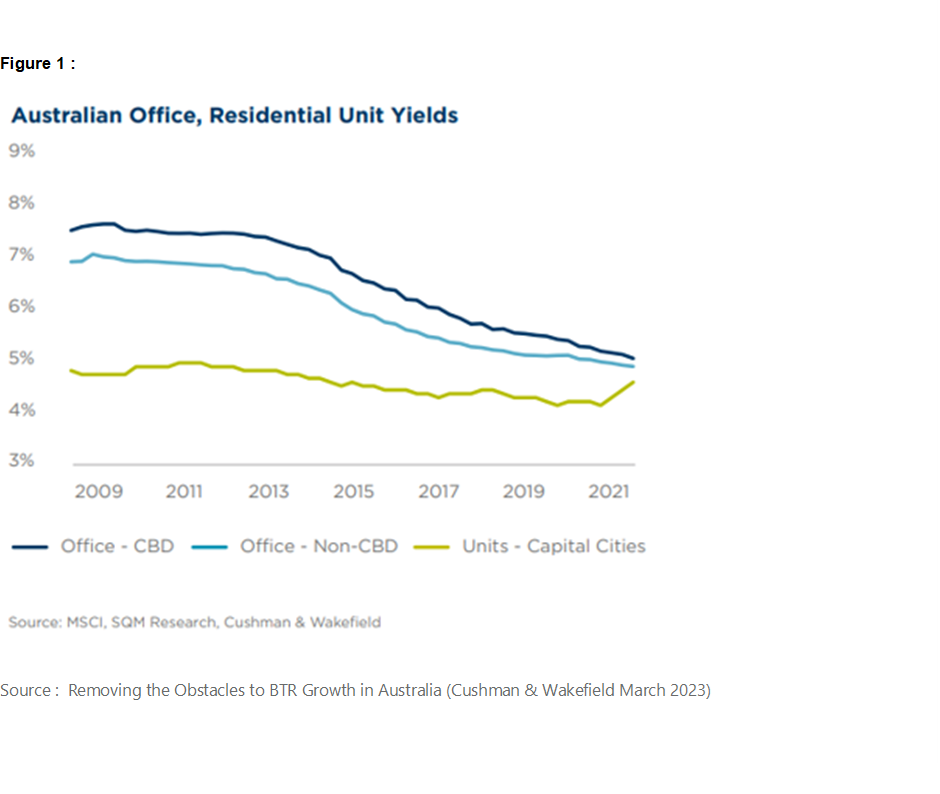

Despite these historical biases BtR sector is starting to gain increased attention as an institutional investment. Driving this increase in attention is not only the longer term favorable macro tailwinds, but also that post 2008 commercial investment yields have declined making those on residential property more attractive as the relative yield differential has contracted.

With a major contraction in the yield differential between residential (units) and commercial property, residential (units) has become a more enticing proposition as income assets for institutional investors. Whether such a contraction in the yield differential will be maintained, and hence the renewed institutional interest in residential projects, is unclear.

A further negative for residential investment from an institutional viewpoint has been the higher volatility in vacancy rates and rents compared to other types of commercial investment. Largely this has been due to the shorter term nature of residential rental agreements in Australia; i.e. normally up to 12 months. That said to the extent that work and consumer habits evolve this may prove less of a negative consideration going forward. Furthermore, an increase in institutional interest in residential property may result in an evolution of the sector and increased interest in longer term rental agreements which provide a greater level of certainty to all parties.

As interest builds in the sector so is the expected growth in the BtR development pipeline. With the usual caveat as developers face pressure on feasibilities due to rising construction and finance costs, investors and operators in the sector should benefit from the growing opportunities in the BtR space over the coming years as momentum grows. To put the potential size of the longer term opportunity in some perspective, according to the Property Council of Australia report dated 4 April 2023, BtR currently makes up just 0.2% of the total Australian residential sector compared to 5% and 12% in the UK and US respectively. If BtR grew to 3% of total residential accommodation, then this would translate to a sector worth around $290bn (currently approx. $17bn) or equivalent to approx. 350,000 apartments (currently approx. 23,000 apartments).

The types of complexes offered under BtR business models?

Though the macro backdrop is promising, as the sector is yet to become well established, the most contentious points regarding BtR in Australia revolve around the type of product mix, or complex design, that will generate the optimal returns for investors. There are two main aspects to complex design with the first being the optimal mix of apartment types. Obviously, the answer will depend upon the type of business model adopted for a complex. While the optimal build form of apartments may be debated there is a consensus that BtR will need to focus on high density accommodation with a minimum building size of 100 units and average size more likely 200+ apartments.

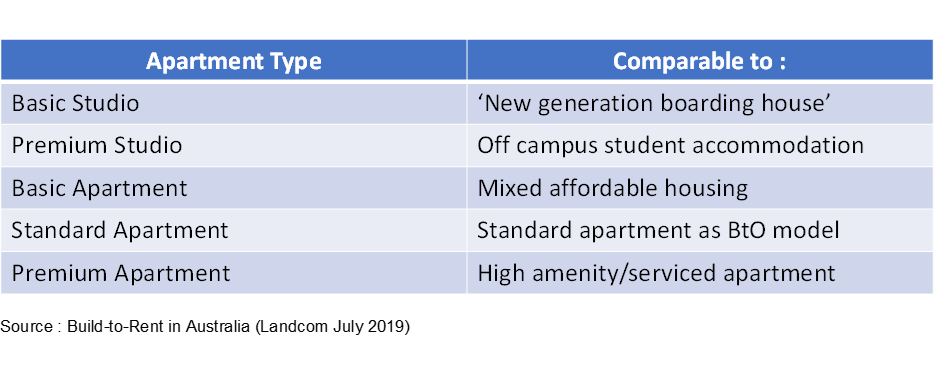

At this point it is worth going into a bit more detail why the apartment type and mix can have a material impact on the returns earned from a BtR development. When considering apartment types the emerging Australian BtR sector can be understood in terms of five types of development projects and resulting housing assets. The five types are described below :

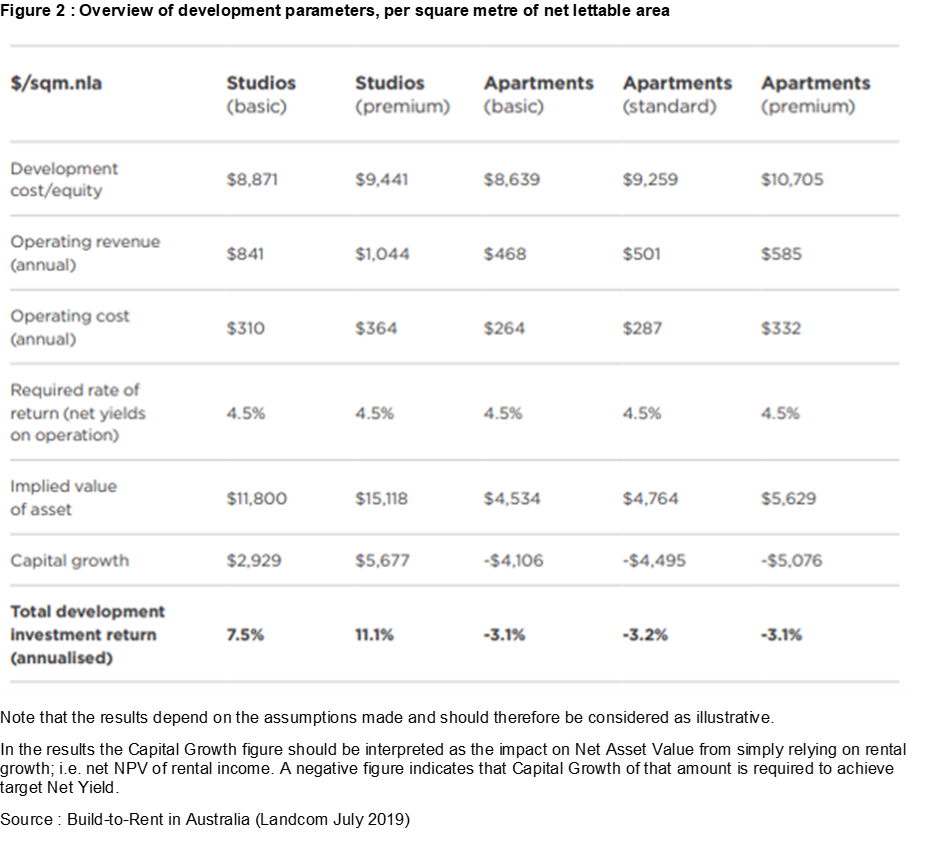

The impacts on composition of returns resulting from the apartment type mix can be better appreciated by considering the analysis undertaken by Landcom in 2019.

The analysis highlights that, based on the parameters set by Landcom, the returns earned on apartments will vary depending on type. More specifically Studio and Studio (premiums) do not require capital growth to earn the targeted return of 4.5% p.a. This becomes particularly relevant for BtR models focused upon earning rental income where the more units that can fit within a building the better. Other types of apartments rely more upon capital growth to generate the required return and so may lend themselves to other types of BtR models. This highlights that (a) the mix of apartment types can have a direct impact on the type of business model which may be preferred by the developer and (b) why much of the institutional investment to date has been in student accommodation which follows a studio type apartment layout and hence relies principally on rental income to generate the required returns.

The second aspect to the BtR model is the range of services which are to be offered to tenants. As the Landcom analysis highlights for BtR models to work most efficiently as income generators there needs, within certain constraints, to be as many apartments in a complex as possible. This implies not only higher numbers of apartments but also that BtR apartments are likely to be materially smaller than their BtO equivalents. Offsetting this is that BtR developments will need to incorporate a range of additional services to attract and maintain tenants. Importantly they need to provide modern amenities such as gyms, wellness/co-working spaces etc as well as being convenient to transport and employment nodes. The requirement for such premium services becomes more important as the unit density increases. Given the early stage of the sector in Australia the optimal mix of services and how they should be priced/provided is still something of a work in progress. Finding the right balance is particularly relevant given that the provision of additional services means that BtR will typically charge a price premium and will therefore tend to rent for more than a suburb’s median price.

Complicating the situation for investors is that most BtR projects to date incorporate material levels of development and leasing risk. Not only is the BtR sector at an early stage of its evolution as an institutional exposure but most developments are (a) more likely to be ‘green fields’ in nature, i.e. utilising the bare undeveloped land to build,’ and (b) by their nature do not lend themselves to material levels of long term pre-leasing. This is in contrast to many other types of property investments where investors can focus on income returns as the project can be derisk materially via the assets being acquired on an ‘as completed’ basis, project involving repurposing/redevelopment of existing properties and/or extensive longer term pre-leasing being undertaken. Within the BtR market investors are involved in the development of an asset from the start and as such assume materially greater risks within the project. Such additional risks should be borne in mind by investors when determining whether BtR is appropriate for them as an investment.

BtR is a new and, potentially, rapidly growing part of the property market which is likely to attract material amounts of institutional funds into residential property. For investors it is important to realise that not only the type of product mix offered but also the business model adopted will have a material impact on the types of returns earned. As with any property investment type BtR is not a panacea that offers guaranteed returns simply because there is a shortage of housing accommodation. The specifics of each project need to be carefully assessed to determine its appropriateness for the types of returns the investor may be looking for. This is particularly relevant in a new sector such as BtR where some opportunities may incorporate material amounts of development risk which may not be suitable for investors seeking more ‘income like’ return profiles. Given the risks involved in an evolving sector it may well pay to be pragmatic and avoid being among the first movers until the parameters around the optimal business model are more established; i.e. it may pay to be a second mover.

3 topics