Does anyone really care about housing affordability?

Since I started writing about and advocating for housing affordability in 2016, the cost of renting or purchasing a home relative to incomes has become even more unaffordable, largely due to poor government policy. Australians have among the highest level of household debt in the world, as well as several of the most expensive average city home prices relative to incomes. Low income Australians are estimated to be spending more than half of their income on rent. New home buyers are estimated to be spending around half of their income on mortgage payments with insurance, rates and repairs to be added on top of that. Australia is a world leader in unaffordable housing.

As we approach a federal election, the cost of living is the preeminent issue. Unless the home is owned outright, rent or mortgage payments are typically the largest expense. Despite promises of affordable housing before the 2022 election, households have experienced soaring rents and mortgage payments. When the combination of higher inflation, modest wage growth, bracket creep and falling real disposable income is included, household budgets have become much tighter. This article looks at why Australian housing has become unaffordable and what our federal politicians can do if they want to fix the problem, instead of just talking about it.

Excess demand has driven the cost of housing higher

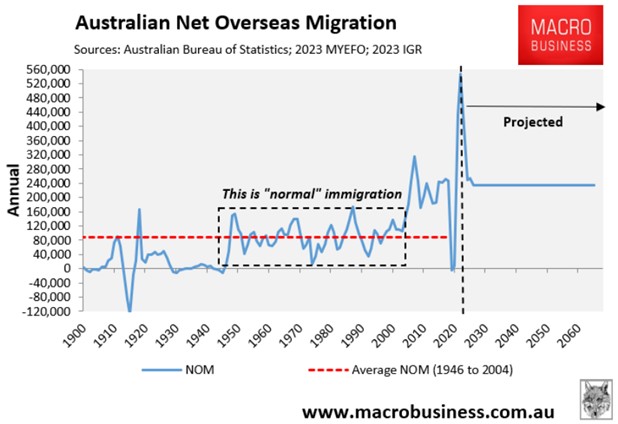

While there are many contributors to Australia’s unaffordable housing problem, by far the largest has been excessive migration. The graph below from Macrobusiness illustrates this clearly: the normal level of net migration for sixty years after the Second World War was just under 100,000 people per year. This increased to an average of over 200,000 per year in last years of the Howard government until Covid border closures commenced. Under the Albanese government, net migration has averaged 471,289 per year. Most of this is temporary migration, with a net 974,543 temporary visa holders added since 30 June 2022.

Some economists and politicians dubiously claim that increased supply is the solution, implying that the private sector can build whatever amount of housing population growth demands. The basic maths of population growth and housing are reasonably straightforward for those who care to look at the ABS data.

The basic maths of housing demand and supply

Under the current Albanese government, net migration has so far averaged 471,289 per year and natural increase (births minus deaths) 104,133 per year, together totalling 575,422. The average number of residents per dwelling is around 2.5. However, simply dividing population growth by 2.5 to calculate how much housing is needed is an error, as this ignores dwellings demolished and that we are building proportionately more units, which typically accommodate fewer people than houses. A more accurate estimate is to divide by 2.2, which indicates we need approximately 261,556 completions per year just to keep up with population growth under the Albanese government.

The Albanese government’s target to build 240,000 dwellings per year has quickly been shown to be fanciful. In Australia’s history we did get to around 90% of the target level from 2016-2018, but the average under the Albanese government has been 175,828 completions per year. Subtracting the housing needed from the recent rate of completions results in a shortfall of approximately 85,728 dwellings per year, which will be a cumulative dwelling shortfall of around 250,000 over this three-year term of the Albanese government. To lift housing completions to match population growth would require more than halving non-residential construction (infrastructure, schools, hospitals, shops, warehouses etc) and reallocating this capacity to residential construction. This isn’t feasible, a rapidly growing population needs both infrastructure and housing.

Some argue that we need to increase the supply of construction workers to increase the supply of houses. There are two simple problems with this. First, the unemployment rate is low in Australia, so we would need to attract workers away from other sectors. As the construction industry is already estimated to make up 9.5% of the workforce, there are issues with how many people would want to voluntarily switch industries without significant financial incentives and how to deal with the loss of workers elsewhere.

Second, importing construction workers should help in the long term, but it makes the problem worse in the medium term as they need somewhere to live when they arrive. Compared to peer nations on a per capita basis, Australia already has a very large construction industry that produces more new dwellings, demonstrating that the cause is excess demand, not inadequate supply.

Where to cut migration?

Given the need to reduce net migration to allow housing and infrastructure to catch up to the population surge, we need to prioritise quality over quantity. Three simple measures will deliver a much better outcome:

· Skilled migration is predominantly for internationals who have a job offer paying at least $150,000 per year

· International students are predominantly engaged in high value courses

· International students need to depart shortly after completing their courses, unless they have a job paying at least $150,000 per year

Skilled migration

For decades Australia has been importing “skilled” migrants to fill supposed skills shortages, yet the shortages never seem to stop. Net migration increases overall demand in the economy, which in turn creates demand for additional goods and services, requiring more employees. Importing a wide range of low and medium paid “skilled” workers to satisfy the demands of employers who either won’t train sufficient staff or won’t offer competitive pay is a lazy and short-sighted policy.

By requiring migrants to have high paying jobs lined up before arriving, we will largely eliminate the issue of importing migrants who have skills and qualifications not accepted by Australian employers. We already have more than enough international graduates driving taxis and working in other low skill jobs.

International students

There are well-documented concerns about some non-university education providers offering low cost, low engagement courses, primarily as visa pathways. A quick internet search finds many websites advertising the cheapest courses for migrants to satisfy visa requirements. English courses and diploma courses start at around $5,000 per year and undergraduate university degrees start at around $15,000 per year. It is bizarre that most of the attention has been focused on university enrolments when lower value and less scrupulous operators are being left alone to rapidly grow their enrolments. It should be reversed, with shonky operators closed and numbers cut at low value courses to create room for higher revenue generating university students.

Lastly, international students are well known to be visa hopping for years after completing their courses, typically working low skill jobs. While Australia’s unemployment rate appears low, there are hundreds of thousands of unemployed and underemployed citizens who could be filling these roles. International students who can obtain high paid work are welcome to stay and ultimately become permanent residents and citizens.

What would a migration cut would look like

Earlier sections in this report have noted that Australia has seen a net 974,543 temporary visa holders added since 30 June 2022 and that trend population growth implies a shortfall of around 250,000 homes during the current term of government. To address the issue efficiently, a drop of at least 500,000 temporary migrants should be targeted to provide rapid relief to renters. A drop of this size should release around 200,000 dwellings back into the market, undoing most of the damage from excessive migration that has occurred in the current term of government.

A drop of 500,000 temporary visa holders would be 17.2% of the 2.903 million current holders of temporary visas as at 28 February 2025. This is comfortably attainable by reducing low wage workers and students undertaking low cost courses, as their current visas expire. A more efficient legal process for determining the claims of former student and work visa holders who have been rejected for subsequent visas is required to help clear the backlog of cases.

There are no solutions, only trade-offs

When the logical solutions discussed above are put forward, several mostly spurious objections are raised. Reducing low paid migration comes with many benefits including higher GDP per capita, greater productivity growth, higher employment and wages - particularly for low paid Australians, lower rents and cheaper houses, less welfare spending and far less spending on infrastructure. The chief objections raised to lowering migration include inflation pressures, lower house prices and lower nominal GDP growth, usually coming from those with vested interests.

Countervailing inflation outcomes

Lower migration would put downward pressure on house prices and rents as the construction industry is able to catch up to the accumulated excess demand. This would naturally reduce a large component of the CPI. Offsetting this would be higher wages in low skill jobs as the pool of low skill workers shrinks. I see higher wages and employment for Australia’s lowest paid workers as a feature, not a bug, and likely to be a much smaller impact on CPI than the benefit from cheaper housing.

House prices will fall

The Albanese government’s position that they want affordable housing without house prices falling is nonsensical. Affordable housing means that the average family can afford to purchase the average house. If house prices were merely to remain at the same nominal level, affordable housing could be decades away given stagnant productivity and wage growth. Like ignoring productivity and tax reforms, this is government shirking its responsibility to act in the national interest.

Australia’s banks are regularly stress tested against a substantial fall in house prices, thus making arguments over a banking collapse spurious. Investors who have bought into overpriced housing should not be given favourable treatment at the expense of middle-income Australians who are being locked out of purchasing a modest home. A reversal of the excess demand for housing would also naturally lead to lower rents for low-income citizens, who are unlikely to be able to service a substantial mortgage and afford to purchase a home.

Lower nominal GDP growth

High migration has allowed Australia’s politicians to boast about avoiding a nominal recession, while a GDP per capita recession has dragged on. Ordinary citizens may not understand the economic terms, but they have experienced the reduced quality of life from falling disposable income, negative real wage growth, and infrastructure pushed beyond its intended capacity. Focusing on high paid migration would lead to higher productivity, reduced demand for government services, capital deepening and increased tax revenue on a per capita basis. All of this would help lift Australia’s abysmal productivity performance, leading to sustainable real wage growth.

What about other policies?

Having reached this point, it should be obvious that Australia’s population has been growing much faster than the construction industry can build the necessary housing and infrastructure. To achieve a rapid turnaround in rental affordability, we need to implement a reduction in Australia’s population in the short term, along with measures that restrict the rate of future net migration. Once that has been done, other policies can start to work at reducing the cost of construction and thus the cost to purchase a new dwelling. There are smart policies and dumb policies being proposed, with brief comments on the major policies below. Longer comments on most of these have been included in a previous report provided to a government inquiry.

Smart policies

Faster and less restrictive planning processes: Consistent, cost efficient and streamlined processes will encourage developers to acquire land and begin building denser dwellings in key transport corridors, as well as converting low value land into new housing developments.

Tax reform: Australia’s tax system discourages working, saving and investing with high tax rates on work income and low risk investments (e.g. bank deposits). Income taxes should be lowered and flattened, offset by a higher and broader GST and the removal of concessional capital gains tax. Stamp duty and development levies should be replaced by a broad-based land tax.

Clean up the building industry: Australia’s building sector is notoriously expensive and unproductive. Cracking down on criminal activity on building sites and phoenix companies stealing from workers, creditors and taxpayers would materially lower the cost of construction.

Dumb policies

Key worker housing: All Australians should have access to affordable housing, not just those in favoured industries or those who can best lobby for subsidised rents. These schemes compete with the private sector for the limited capacity of the construction sector and often involve taxpayer subsidies.

Shared equity and debt guarantee schemes: Government co-investments rarely stack up for taxpayers and residential property is unlikely to be an exception given elevated property prices. Governments guaranteeing the debt of higher risk borrowers is likely to result in taxpayers being stuck with significant losses during the next recession. These policies encourage potential home buyers to save less and borrower more, putting upward pressure on prices and creating greater systemic risk for the financial system.

Rent controls: Study after study has shown that rent controls decrease the supply of new housing and results in less maintenance on existing rental accommodation. This a good example of Walter Wriston’s quote: “Capital goes where it is welcome and stays where it is treated well.”

Rental assistance: Increasing welfare payments to selected individuals for rental accommodation raises the ability of recipients to compete for the current limited supply, pushing up rents. It leaves those who don’t receive the payments worse off, as they see their rents rise and may lose out to those who do receive assistance. These payments do almost nothing to increase housing supply, instead functioning as a handout from taxpayers to landlords.

Making interest payments on the primary residence tax deductible: Providing a tax deduction to higher income earners who borrow more is effectively a subsidy from other taxpayers, including low-income renters.

Force the RBA to cut the Cash Rate: Australia has a very high level of household debt, with low interest rates over the last decade and current tax settings (concessional capital gains tax, high income tax rates, negative gearing) encouraging Australians to borrow aggressively and purchase property. Reducing the Cash Rate encourages potential purchasers to save less, borrow more and bid up house prices. Savers have suffered low or negative real returns on low-risk investments over the last decade, there needs to be a greater incentive for saving, not borrowing.

Postscript: Why does the left oppose helping poorer Australians?

One consistent theme I’ve found in writing about housing for nine years is that governments, think tanks and media outlets that are politically left are the most unwilling to accept the facts about Australia’s housing situation. The Albanese government has had two housing ministers, both of whom have consistently denied that excessive migration is in any way responsible for Australia’s housing shortage. My direct correspondence to them and to the National Housing and Homelessness Plan inquiry, has been completely ignored. The Greens have at least been polite enough to respond, but they too openly deny that excessive migration is a contributing factor. Instead, they promote rent controls, which have a long history of worsening housing shortages worse.

The Grattan Institute (a left of centre think tank based on its long history of promoting higher government spending and higher taxation) has had much to say about housing affordability. Their reports have consistently ignored the demand created by excessive migration, focusing instead on minor contributing factors. They continue to endorse migration for workers earning below average incomes and recommend that the federal government increase rent assistance, which is effectively a handout from taxpayers to landlords that does almost nothing to increase supply.

As a point of balance, the politically right, Centre for Independent Studies has consistently focused on easing planning restrictions as their preferred solution. This too ignores the reality that the construction industry cannot keep up with excess demand. Supply reforms alone cannot fix excess demand, unless their plan is for purchasers of new blocks to live on them in tents and caravans.

While the ABC has been very good at highlighting the housing affordability problem, it has been largely unwilling to mention migration. They have consistently chosen to quote “experts” who promote supply side reforms but almost never include comments from those who call out the obvious demand side issues. The Q&A program has addressed housing affordability several times, yet they’ve not had a panellist willing to state the obvious facts about excess demand. There might be some hope for the ABC though, Alan Kohler’s article pointing to business and international student educators directing migration policy, as well as a short segment showing that supply simply can’t keep up with demand, will hopefully encourage other ABC journalists to bring some balance to their reporting.

I’ve also written to several social welfare groups that publicly advocate for greater welfare spending for low-income Australians. They are happy to write long reports highlighting the unaffordability of rental housing and appear widely across media outlets promoting their solutions. However, when I’ve written to them about reducing migration to increase the wages of low income Australians and reduce the rent they pay, they have been unwilling to respond.

3 topics