Economists and forecasting: Why do we have different opinions?

How is it possible that looking at the same sets of data figures can yield a different outlook on the economy? In this wire, we look at the key areas of the economy that we have a different outlook on, compared to the RBA.

The “dark art” of forecasting

Humility is very much needed in forecasting, as you simply cannot get everything right. Everyone likes having a go at predicting the future and when economists get it wrong, they often get told how wrong they were (mostly because their forecasts are published!). Some people tell me that economist forecasts have a track record that’s as good as a weather person.

Data points can be lagging, coincident or leading indicators of the future but may be more or less useful at different points in the cycle and also change depending on the nature of each economic cycle. The pandemic has arguably made data interpretation more difficult because historical rules have proven to not always work and seasonal adjustment methods have been compromised. Some analysts also like to massage or manipulate the data to tell a story that fits their narrative.

We are more optimistic about the trajectory for inflation

The RBA upgraded its inflation forecasts in the August Statement on Monetary Policy. It expects headline consumer price inflation to be at 3% by December 2024 (because of the Federal and State governments' cost-of-living initiatives) but to spike back up to 3.7% a year later as these measures drop out, before returning to 2.6% year on year by December 2026 (the mid-point of the target).

Trimmed mean inflation is expected to be at 3.5% by December this year and be just under 3% in December 2025, reaching the mid-point of the target by late 2026. This forecast sees inflation back at the RBA’s midpoint around 6 months later than the last estimate. The RBA’s higher inflation assumption is based on estimates that demand will run above supply for longer than previously expected (i.e. there is excess demand) and drive higher inflation which was also reflected in the upside revisions to economic growth.

We are more optimistic about the near-term trajectory of inflation. We expect underlying inflation to be at the top end of the target band by mid-2025 and within the 2-3% target midpoint by early to mid-2026, around 6 months ahead of the RBA. The inflation profile across our major global peers indicates that further goods disinflation will continue and slow services inflation.

Wages growth in Australia is lower compared to peers (currently at 4.1% year on year versus 4.7% in the US, 4.7% in the Eurozone, 5.4% in the UK and 4.3% in NZ). Population growth will slow to 2% over the year to June 2024 from 2.5% in 2023 which will lower growth in housing demand and reduce pressure on rents and new dwelling construction costs. And we expect that administered price inflation will soften with lower headline inflation as a result of the government cost of living measures.

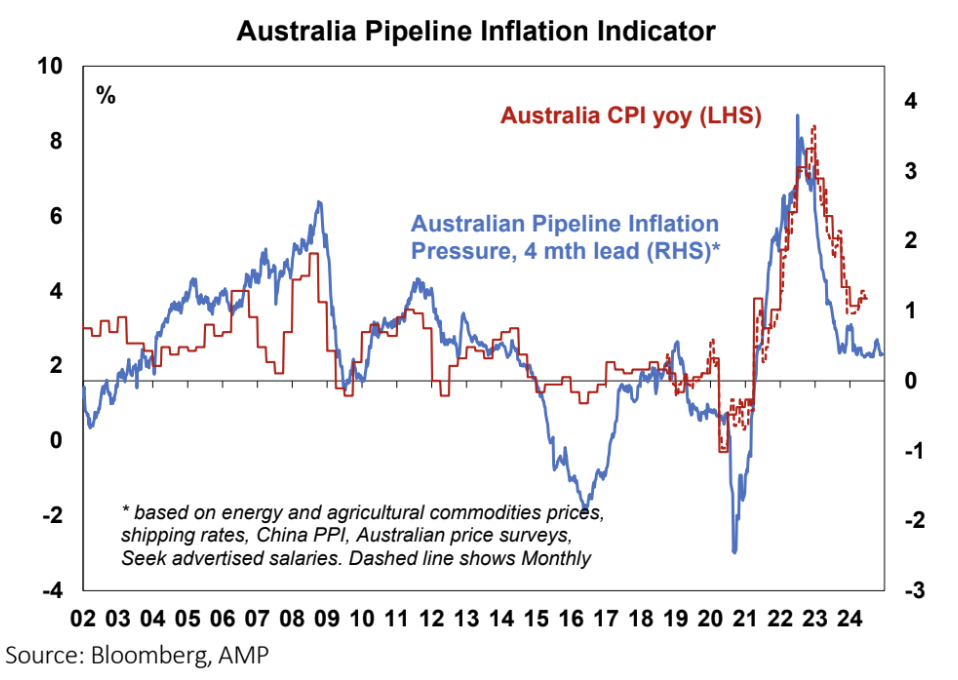

Our leading indicator of inflation (see the chart below) is based on commodity prices, shipping rates that affect Australia, the Chinese producer price index, Australian price surveys and Seek advertised salaries. It shows some further downside to inflation is expected and has been a good guide to the trends in this inflation cycle.

We are more concerned about the consumer

The RBA is forecasting better household consumption over the forecast period as household disposable income improves (from tax cuts, lower inflation and a decline in interest rates in the forecast horizon as the RBA uses market pricing for interest rates in their forecasts) and a rise in household wealth supporting consumption.

While we agree that the average consumer in Australia might be doing okay, it is the spread of outcomes across consumers that is more concerning. Older households (like Baby Boomers) are doing well because they have little to no debt and large increases in wealth. Consumer spending for those aged over 65+ has not been declining. However, younger household groups aged under 45 who have mortgages or rent have been cutting back spending and in our view have exhausted accumulated savings to draw upon. And they are the group that changes their spending more in relation to changes in their financial conditions.

We see poorer GDP growth in Australia - which means low per capita growth will persist and we are more concerned about the outlook for the US

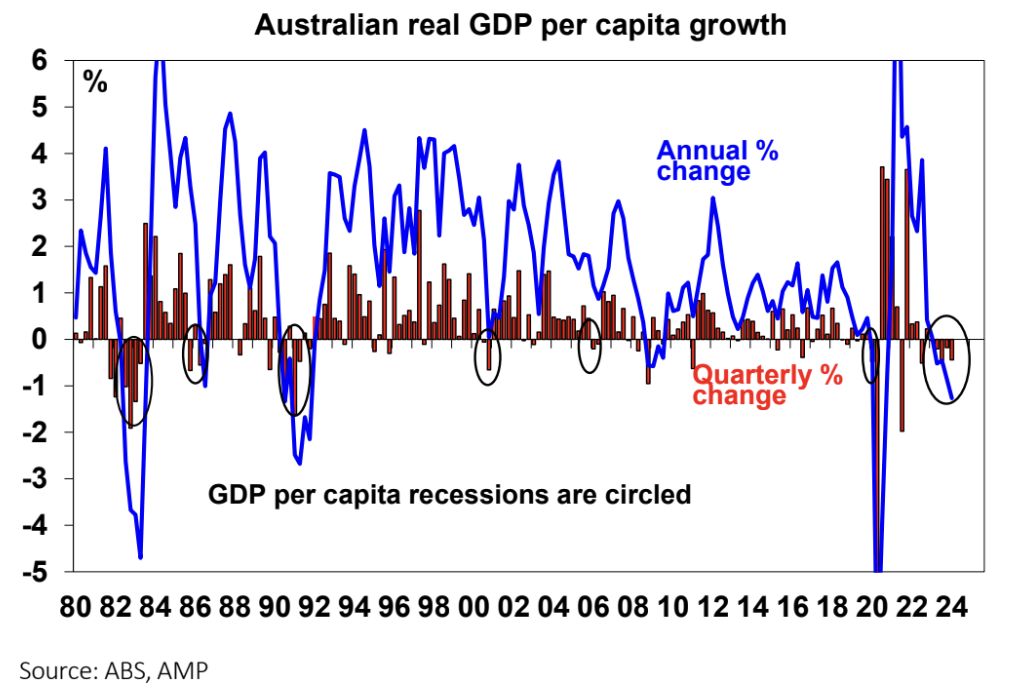

The RBA sees GDP growth of 1.7% by December 2024 and 2.6% by June 2025 while we expect 1.3% and 1.7% respectively which means that per capita GDP growth will remain negative in the near term before improving slightly in 2025. Per capita GDP growth has already been negative for the last five quarters which means that living standards are going backwards!

We expect softer consumption growth and a lower contribution from public spending relative to the RBA’s forecasts. We are also concerned that a drop in population growth in 2024 and onwards will make a larger-than-expected dent in nominal growth in the economy offsetting the boost from tax cuts.

We are also more negative about growth in the US economy (and see a 50% chance of a recession in the next 12–18 months) although the US is a small trade partner to Australia (around 4% of exports go to the US), the negative sentiment hit from weaker US GDP growth could impact Australia as would the flow on to our trading partners, particularly China.

Implications for investors

The risks around the pathway for the RBA cash rate are reflected in market pricing for interest rates which is based on the probability of cutting, holding or hiking the cash rate. Market pricing moves around a lot and is influenced by what happens in international markets (particularly the US).

We think that economic data will continue to weaken over the coming months and inflation will surprise to the downside which will allow the RBA to start cutting interest rates in early 2025. While the data may slow enough by late 2024 to justify a rate cut, given the RBA’s latest rhetoric, they do appear reluctant to cut interest rates, in case it provides a second-round tailwind to inflationary pressures.

Diana is the resident economist on Livewire's Signal or Noise.

4 topics