End of a golden era for profits?

Let’s step back from the daily market gyrations to consider secular trends impacting longer-term asset returns and strategic asset allocation decisions. If we assume that a prolonged period of declining and ultra-low interest rates is over, then the rate at which future corporate profits, cash flows and dividends are discounted will be higher. Higher discount rates imply lower equity valuations (lower price-to-earnings ratios). If profitability is also peaking, then the inescapable conclusion is that stock market returns will likely be lower in the years to come than we’ve come to expect in our lifetimes. Are we doomed to this fate or are there factors that could turn the tide?

What the data show

We begin with a review of the data—specifically the US national income accounts(1)—which capture economy-wide measures of profitability. National income estimates of profits include listed and unlisted firms, small businesses and sole proprietorships, and hence provide useful insights into broad drivers of overall business performance.

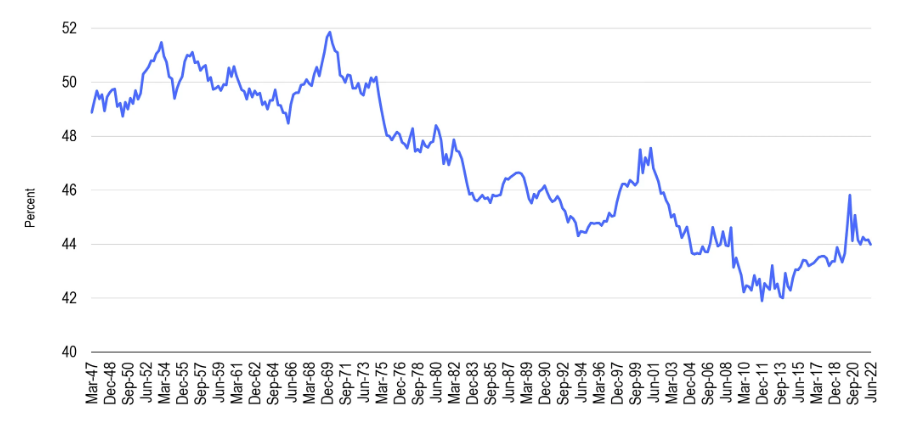

As Exhibit 1 demonstrates, the share of pre- and after-tax corporate profits in the United States has been on an upward trend over the past three decades. To be sure, periods of deep recession (e.g., 2008 and 2020) sharply interrupted that rising trend, but the unmistakable tendency since 1990 has been for corporate profits to garner an ever-larger share of the economy.

According to the most recent figures (second quarter 2022), US after-tax corporate profitability reached its highest share of gross domestic product (GDP) in nearly 70 years. Pre-tax profits as a share of GDP were also near their postwar record highs. It is also interesting to note that corporate profits after tax have grown more than pre-tax income as corporate tax rates have fallen.

Macroeconomic and listed-company definitions of profits can differ—for example when accounting changes are significant or financial stress is acute. But, in general, national income-based profit measures and those for listed companies move broadly together. For example, S&P 500 corporate profit margins have been on a multi-decade upswing that saw average margins rise from 6% in the early 1990s to a postwar record of 15% on the eve of the pandemic.(2) That bears a strong resemblance to the rise in profits as a share of GDP depicted in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Pre- and After-Tax US Corporate Profitability as a Percentage of GDP

March 31, 1947–June 30, 2022

Sources: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Macrobond.

What has been responsible for the rising share of profits in GDP?

According to a recent paper, falling borrowing costs and tax expenses have resulted in as much as one third of the increase in aggregate US corporate profitability in the past 20 years. For example, two decades ago interest and tax expense accounted for roughly 45% of S&P 500 Earnings Before Interest and Tax. Today, that figure is about 26%. Falling interest expense has been a major contributor, driven entirely by lower borrowing rates even as total borrowing has risen.(3)

The same is true for effective corporate tax rates—the actual tax paid as a share of pre-tax income. Twenty years ago, the effective corporate income tax rate was over 30%. Today it hovers just above 15%.(4)

Labour costs also matter, as they are the single biggest cost for most firms. So, it is worth delving a bit deeper into the dynamics of employment costs and why, in particular, labour has fallen behind over the past sixty years. As Exhibit 2 shows, the share of labour income in GDP has been declining in the United States over the past half century.

Exhibit 2: Labor Share of Income in GDP?

March 31, 1947–June 30, 2022

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The answer resides in diminishing labour bargaining power as rates of union membership and instances of collective bargaining have declined. In the early 1980s, for example, one in five American workers belonged to a union. Today, the figure is roughly one in 10.(5)

We believe bargaining power has also fallen as workers feel they must compete against lower cost labour from abroad (via globalization and outsourcing) and against the threat that their jobs may disappear due to automation. Explicitly or implicitly workers have responded to those threats by accepting low, stagnant or even falling real incomes in a bid to preserve job security. The consequence is that the fruits of rising productivity have flowed disproportionately to capital in the form of profits rather than to workers in the form of higher compensation. Notably, the past half decade has seen some recovery in labour share, which if sustained could begin to put pressure on corporate profit margins.

Another source of higher profits has been a greater concentration in industry (i.e., less competition), which enables higher firm price markups over costs. A 2018 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) paper documents the rise in industrial concentration (industries dominated by a few firms) and increases in markups (margins) as sources of rising profitability (notably in the United States and Japan, but less so in the eurozone).(6) Another study indicates that some three quarters of United States industries have demonstrated a rise in firm concentration (declining competition) this century.(7) Firms enjoying ”first mover advantage” are dominating industries like online retailing, software services, search engines and media.

Where to from here?

As noted, many key factors driving up profitability are now stalling or reversing. We believe effective corporate income tax rates probably cannot fall much further. Efforts are underway in many countries to establish minimum company income tax rates and to eliminate the use of multinational tax havens. Under the US Inflation Reduction Act, for example, a threshold rate of 15% will capture higher taxes from a select group of large US firms (primarily in the technology sector). In our opinion, it is also difficult to envisage further rounds of large corporate tax cuts in the years to come given the budget pressures faced by the United States and most other countries.

Interest expense is also likely to increase due to rising borrowing rates, in our opinion. Over time, as companies finance and refinance their operations at higher borrowing rates, the cost of debt servicing is likely to rise.

With labour expense being most firms’ largest cost, much attention is paid to tight labour markets and rising wages. Nominal wage growth has clearly accelerated. Firms also appear to be hoarding labour even as the economy slows. But it is also important to note that real wages (the difference between wage and price inflation) are negative. Workers are not yet making up ground in inflation-adjusted living standards. Economic anxiety remains high (witness extraordinary low levels of household confidence) and with a recession looming, worker bargaining power could remain weak.

On the other hand, globalization of labour markets may have peaked following big shocks to globalization via tariffs, trade wars, the pandemic and rising geopolitical risk. Deglobalisation could help restore worker’s bargaining power. However, bargaining power will remain constrained by the ever-rapid pace of innovation and the threat to jobs posed by automation.

What’s the bottom line for the bottom line?

By using the United States as the test, we believe a variety of factors suggest that a golden era of rising profitability is coming to an end. Cyclically, profits are at risk from a near-term slowdown or recession. Fragmentation of global markets and falling participation rates may boost labor’s bargaining power. Rising borrowing costs and budgetary pressures make it less likely that profit growth can be sustained through interest and tax expense.

Two factors may play a big role in what happens to profitability. The first is whether governments around the world will more closely scrutinize and potentially roll back the market power of dominant firms in concentrated industries. Minimum global taxation is one step already underway. Antitrust could follow. The second is productivity. We live in times of unprecedented innovation yet output per hour of work grows at paltry rates. If productivity growth accelerates then a growing pie could accommodate larger slices for both labour and capital.

The positive feedback loop of lower rates and higher profits over the past three decades has ushered in a very favourable environment for asset prices. This loop may be reversing to create a period that will require much more careful attention to asset allocation decisions, as the rising tide has lifted most types of investments toward valuations, implying that the benign conditions would continue indefinitely. While the capital/labour dynamics may be shifting, it is not the death of capital, investors will simply need to adjust to this new reality to achieve their return objectives.

Never miss an insight

Stay up to date with all my latest insights by hitting the follow button below, or visit our website for more information.

As Franklin Templeton’s Chief Market Strategist and Head of the Franklin Templeton Institute Stephen Dover leverages the knowledge of the firm’s autonomous investment teams to provide global capital market and long-term investment insights...

Expertise

As Franklin Templeton’s Chief Market Strategist and Head of the Franklin Templeton Institute Stephen Dover leverages the knowledge of the firm’s autonomous investment teams to provide global capital market and long-term investment insights...