Global capital investment in energy needs to more than double by 2030

The energy industry has been under-investing since the peak of 2014 but is expected to expand aggressively over coming years. During the last decade, world energy investment actually declined by 35%, as green spending hasn’t picked up quickly enough to offset the decline in fossil fuel investments. Further, oil and gas CAPEX had been on a declining trend until recently, as investors have been skittish about long-term demand prospects in a decarbonizing world.

“Shortages and greenflation will end the age of idealism on energy policy... a chaos of mixed signals—stigma, virtue-signaling, subsidies, legal cases and regulations—means that investment in the energy industry is running at less than half the $5 trillion annual rate needed to get to net zero by mid-century.” Sourced from The Economist, "Energy investment needs to increase - so bills and taxes must rise", 2021

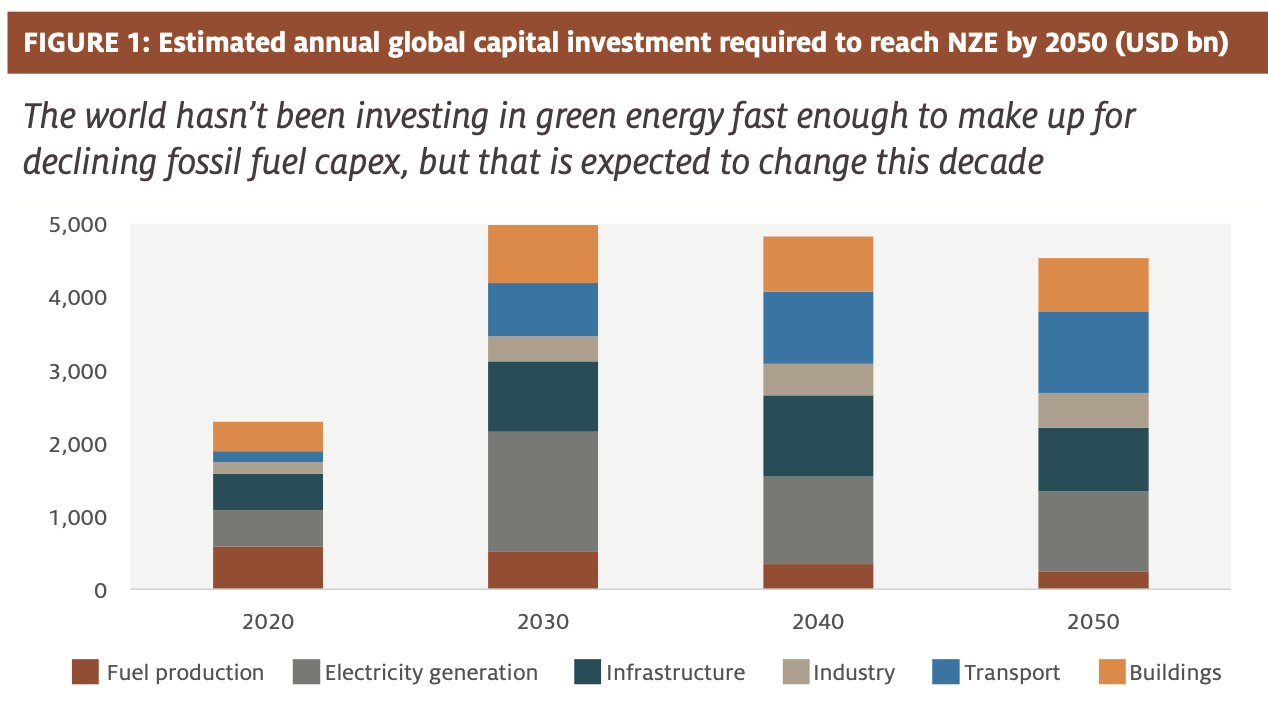

If Net Zero Emissions (NZE) aspirations are to be met, annual CAPEX needs to more than double by 2030 (Figure 1). Aside from fossil fuel production, the required investments in electricity generation and infrastructure are truly massive. Moreover, the average CAPEX intensity of low carbon energy developments is roughly twice that of hydrocarbons. While progress has been made, it is clear the required investments in green energy are daunting and, until now, have not been ramping up nearly quickly enough.

We’re going to need a bigger shovel: The transition involves enormous increases in demand for numerous commodities

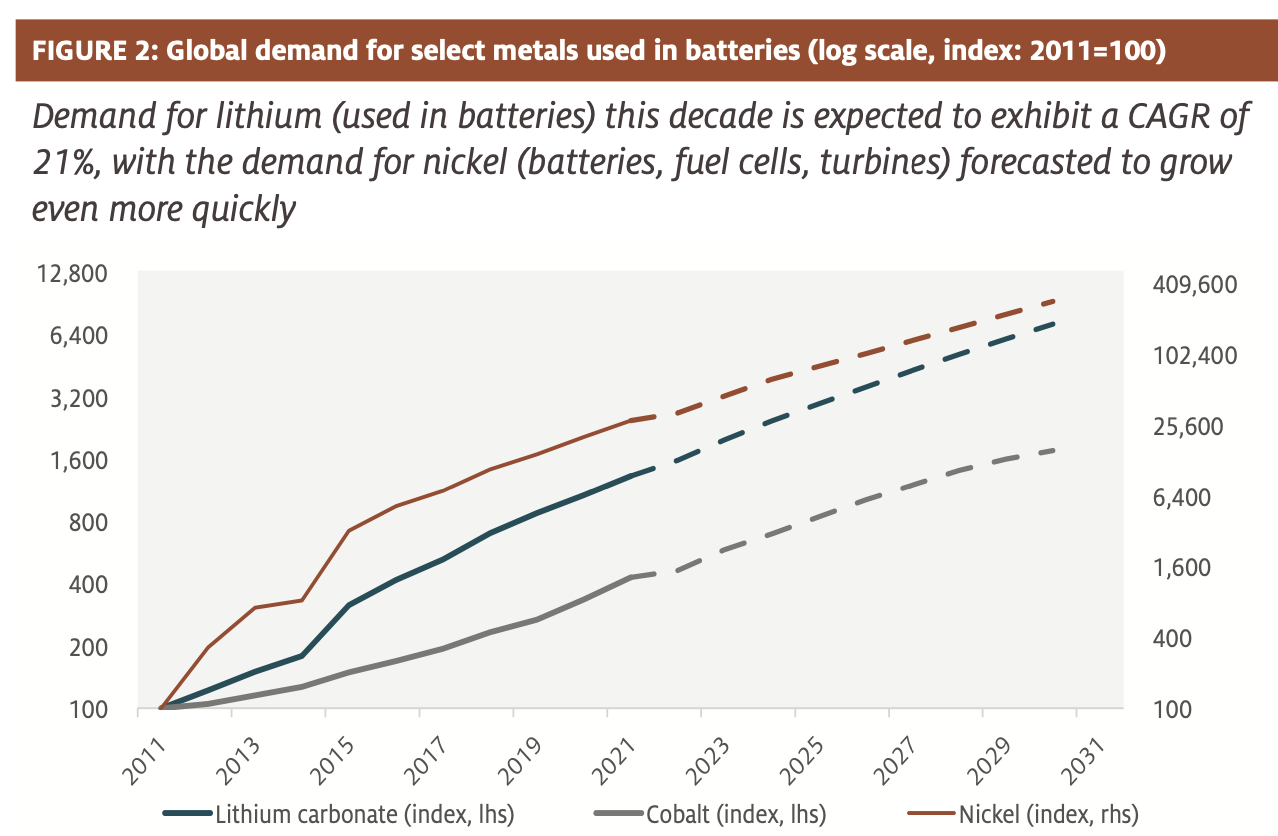

In addition to requiring enormous capital investment, the transition to NZE will also be metal-intensive, with many forecasters expecting the market size of such “green metals” to increase seven-fold by 2030 (Figure 2). To illustrate, battery production is growing exponentially and requires lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite and manganese. Similarly, fuel cells need cobalt, palladium, platinum, graphite, copper, nickel and titanium. The laundry list could be expanded to include wind turbines (nickel, zinc, molybdenum), photo-voltaic cells (silicon metal, gallium, indium, selenium), and many others.

“With the move to electric cars, demand for critical minerals will skyrocket (lithium up 4300%, cobalt and nickel up 2500%), with an electric vehicle using 6 times more minerals than a conventional car and a wind turbine using 9 times more minerals than a gas-fueled power plant.” - Daniel Yergin

Source: Bloomberg BNEF, U.S. EIA, IEA, McKinsey, “The raw-materials challenge: How the metals and mining sector will be at the core of enabling the energy transition,” Jan 2022 and “Critical Raw Materials for Strategic Technologies and Sectors in the EU,” European Commission, 2020

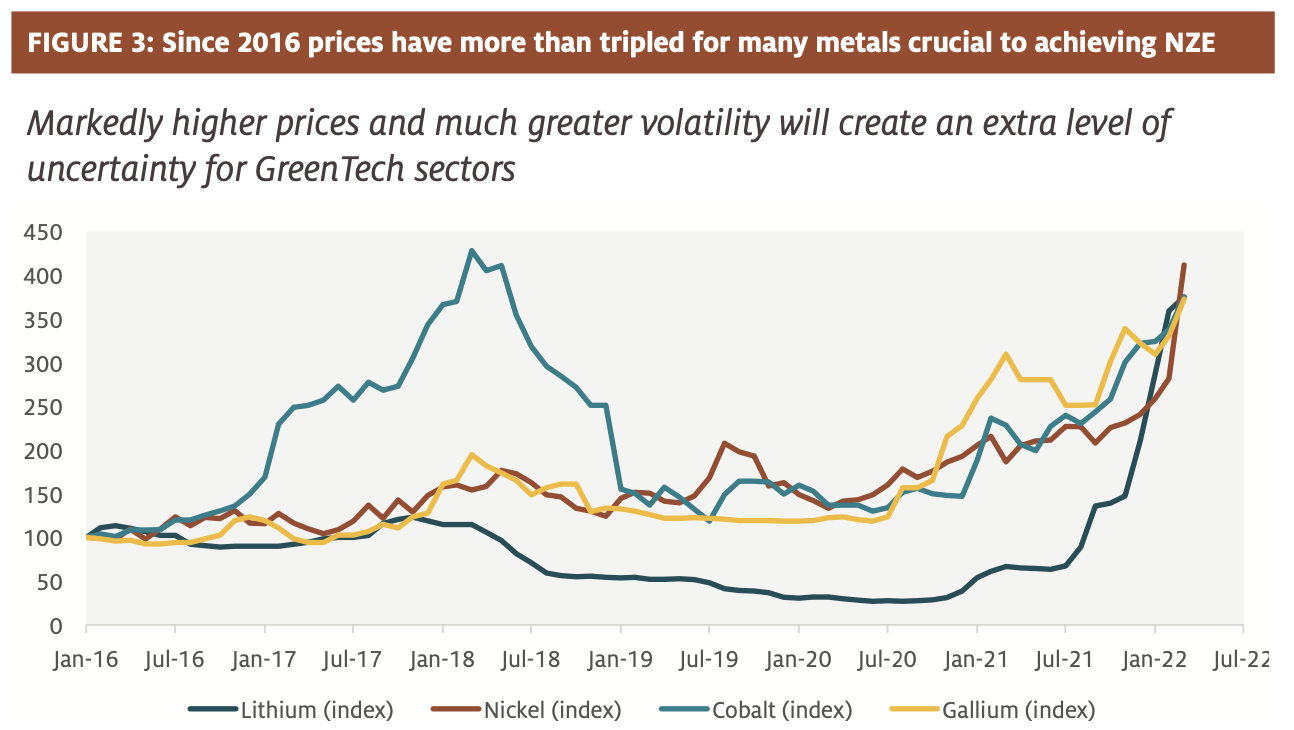

Reflecting the dramatic increase in demand, prices have already soared for most green metals (Figure 3). Further, since metals and mining is a long lead-time, highly capital-intensive sector, price surges and bottlenecks will be unavoidable.(1)

Battery producers, fuel cell manufacturers and others will need to factor in potential resource constraints, with higher and more volatile prices, into their plans to scale and grow. This leads us to the third reason we expect moderately higher inflation as a result of the transition to NZE, Green Premiums.

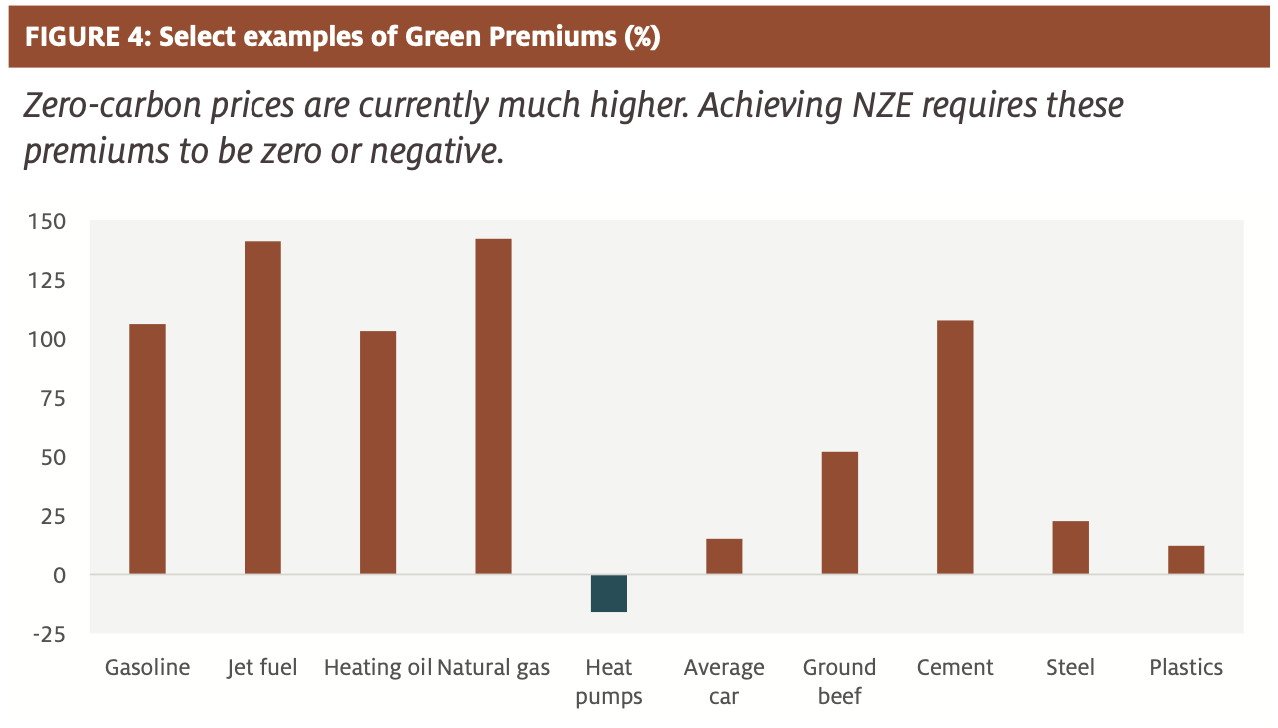

Reducing the green premium: The pivotal importance of achieving scale

The Green Premium represents the current, additional cost of choosing a clean technology over a traditional one (Figure 4). Their calculation involves a host of assumptions, so they are best treated as rough estimates. To achieve NZE, is it crucial to eliminate Green Premiums, which can be done by either making green technologies cheaper (through innovation and scale) or fossil fuels more expensive (through carbon taxes or regulations). Ultimately, premiums need to be zero or negative to incentivize consumers to choose the clean option. Until then, the transition involves higher costs and is inflationary.

Source: Breakthroughenergy.org, “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need,” Bill Gates, 2021, and “Speed and Scale: An Action Plan for Solving our Climate Crisis Now,” John Doerr, 2021.

The first approach to eliminating Green Premiums is by innovating and scaling up production to reduce costs. For Green Tech, the best way to think about economies of scale or experience effects is Wright’s Law. It is named after an engineer who, while studying airplane manufacturing almost a century ago, determined that costs declined by 15% with every doubling of production.(2)

The considerably more famous Moore’s Law, which predicts the number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years, can be viewed as a special case or variant of Wright’s Law.

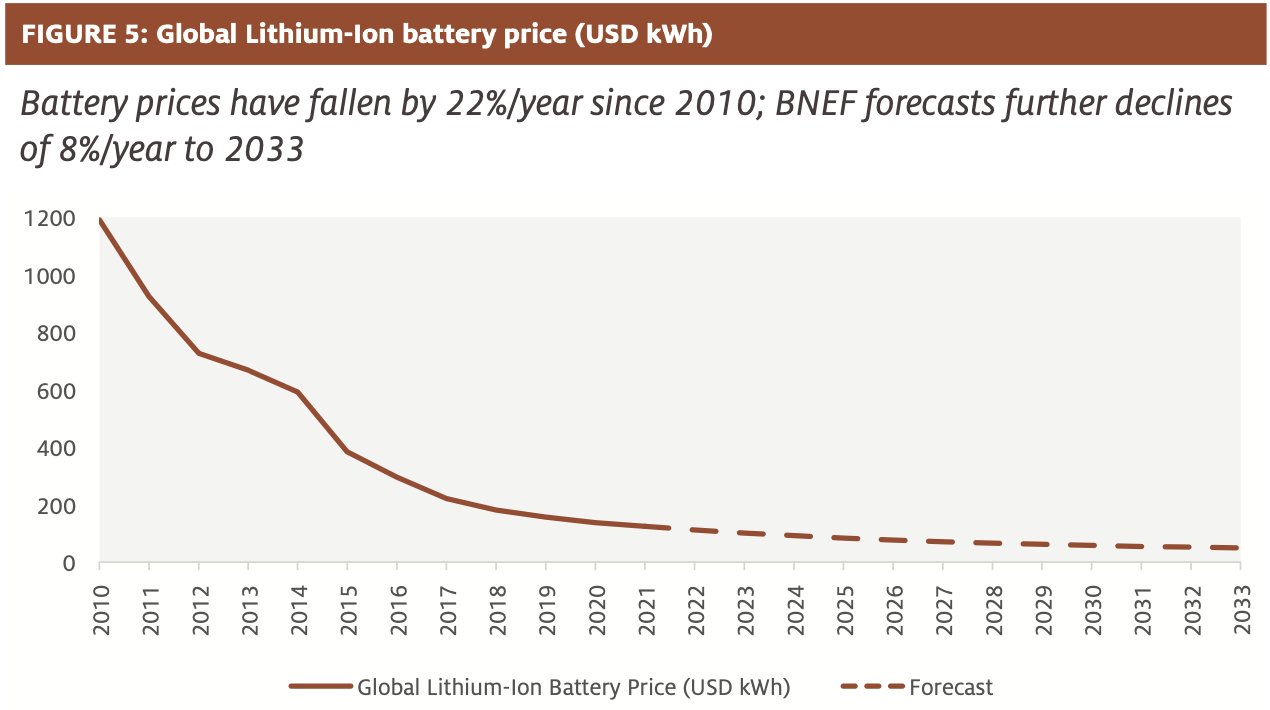

We now provide two examples of Wright’s Law, to illustrate how ramping up scale can reduce Green Premiums. The first concerns lithium-ion battery prices, which have plummeted over the last decade (Figure 5). On some estimates, the magic number that makes EVs competitive with internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles is $100/kWh. While BNEF previously expected the battery industry to reach that mark in 2023, higher commodity prices have likely pushed the date further out by a few years.

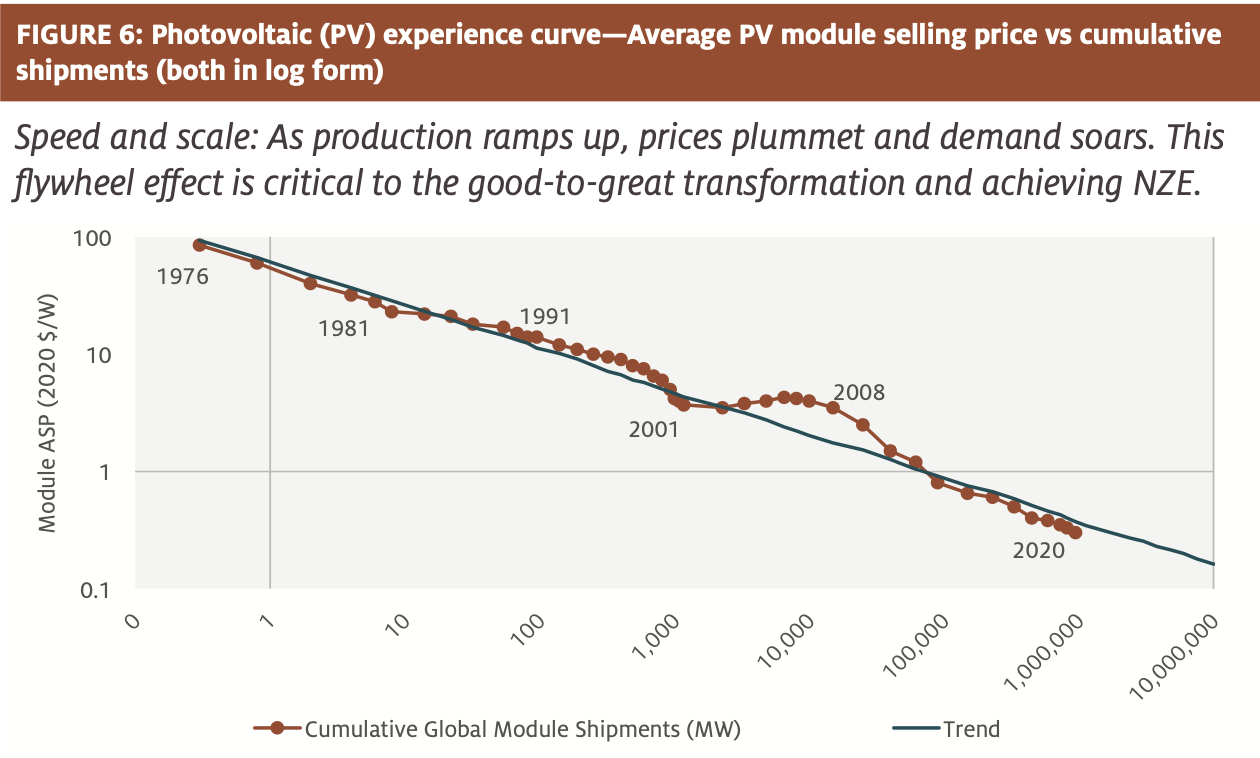

A second example of Wright’s Law concerns Photovoltaic (PV) modules. Prices have been on a declining trend, by about 10% per year and, since 1976, there’s been a 20% cost reduction for every doubling of cumulative shipments (so a bit faster than Wright’s 15%). This has driven the price down from $100/W in 1976 to $0.33/W in 2020 (Figure 6).

Source: “Solar Futures Study”, U.S. Dept of Energy, Sept 2021 and “H1 2021 Solar Industry Update”, National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Government policy can play a big role in helping innovators drive Green Premiums lower. This includes government funded R&D and infrastructure investments (e.g., of the electricity grid), as well as supply- side subsidies to incentivize production, and demand-side subsidies to encourage consumers. Unfortunately, though, today’s highly polarized environment has made it challenging to move forward on such policies. This is also the case for carbon taxes, which are crucial to leveling the playing field and ensuring fossil fuel prices fully incorporate their true social costs.

The tragedy of the Commons: Carbon pricing vs command-and-control regulation

By progressively increasing the price of carbon to reflect its true cost, governments can nudge consumers and producers toward more efficient decisions and encourage innovation that reduces Green Premiums.

Bill Gates

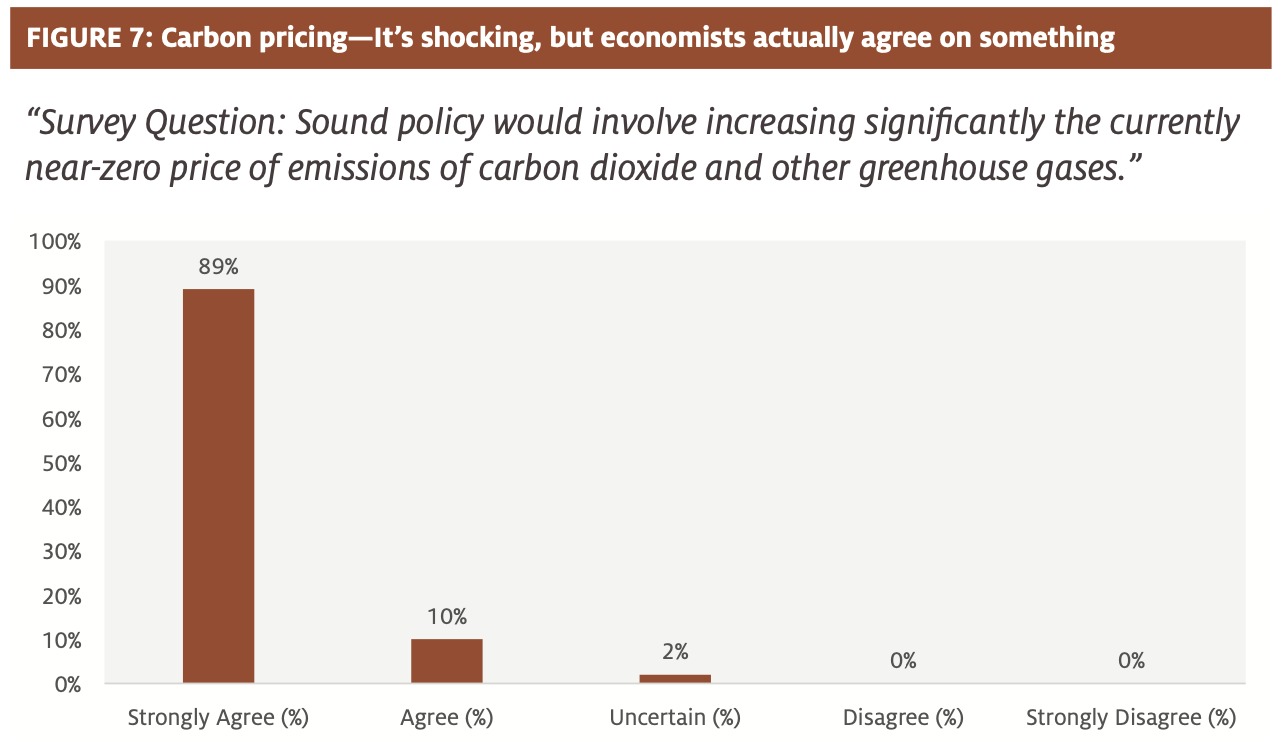

Whether it’s a carbon tax or a cap- and-trade system, putting a price on emissions is one of the most important things we can do to eliminate Green Premiums. Carbon pricing is the classic economist’s solution to climate change, and the most efficient way to incentivize the transition from fossil fuels to green energy.(3) The objective is to engage the power of market forces to “internalize the externality,” ensuring the price of carbon fully reflects both private and social costs. Given this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that economists believe, almost unanimously, that a rising carbon price is essential to achieving NZE (Figure 7).(4)

Source: University of Chicago, Panel of Economic Experts, (VIEW LINK), 2021

What is the optimal carbon price and what would be its impact on inflation? It’s a tough question, but models typically suggest beginning at a price of around $40 per ton of CO2 and then gradually increasing the price toward $200. As Nordhaus explains, “An effective policy is one that ramps up gradually - to give people time to adapt to a high-carbon-price world, to give firms a signal about the economic environment for future investments and to tighten the screws increasingly on carbon emissions.”

The estimated impact on inflation depends on a variety of assumptions, but a reasonable baseline features an increase in inflation by about 25 bps per year over the medium-term. An alternative scenario involves abruptly increasing the carbon price to $100 in one fell swoop, a policy that would likely increase inflation by 2.5% over one or two years (and result in fossil fuel demand declining by 15%).

Alternatively, if the carbon price was raised to $100 gradually, say over a decade, one study suggests energy prices would rise by 25%. There would also be a sizeable substitution away from fossil fuels, as their costs would be multiples higher. For example, Nordhaus estimates the cost of electricity generated by an existing coal plant would increase by 123% with a carbon price of $40 and by 619% with a price of $200. The corresponding percentages for natural gas are 38% and 184%, respectively.

So far, 67 jurisdictions have introduced carbon plans. This includes the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, which was introduced way back in 2005 and was followed by Japan and California in 2012, Korea in 2015 and China last year. However, these plans only cover 22% of global emissions. Moreover, the World Bank estimates the average global price in 2018 was only $2 per ton of CO2, a dismally small fraction of what is required to achieve NZE.

Congress flunks econ 101

Even though carbon pricing is a critical feature of any credible plan targeting NZE, introducing such a scheme remains politically challenging in the U.S. This is truly unfortunate, as it opens the door for command-and-control regulations, which are highly inefficient and will require enormous bureaucracies at all levels of government to implement and enforce.

Lawyers and incumbents would be the only beneficiaries. Further, overreliance on convoluted regulations greatly raises the costs of the transition relative to a market-based approach, resulting in consumers facing markedly higher energy prices.

While this paper is primarily concerned with the implications of NZE aspirations for inflation, it is worth emphasizing that green accounting also reveals some striking findings regarding national output and growth. If government statistics adequately corrected for carbon emissions, U.S. output would be about 10% lower. However, the good news is that national economic growth would be about 40 bps higher (i.e., averaging 2.45% rather than 2.03% for the post-1970 period). This rather paradoxical result occurs because the emissions of most pollutants have been declining relative to the overall economy since the Clean Air Act of 1970. As Nordhaus emphasizes, “The finding that environmental policies are adding to genuine economic growth is important for debates about environmental policy ... those who complain about the impacts of environmental regulations on economic growth are really complaining about measurement, not actual impacts.”(5)

From brown to green energy: The handoff will be messy

Having examined the four reasons to expect moderately higher inflation over the medium-term, we now discuss the transition, which is a monumental undertaking and unlikely to proceed smoothly. Fossil fuels currently satisfy 83% of global energy demand (79% in the U.S.) but to achieve NZE this needs to fall toward zero. Counterbalancing this decline, the IEA predicts solar and wind will account for 70% of power generation by 2050, up from 9% in 2020. It is difficult to exaggerate the scale and scope of this challenge.

While “Electrify everything, decarbonize everything” makes for a great slogan, the actual implementation is mind-bogglingly complex. We are changing the underlying structure, the foundations of a hugely complicated and labyrinthine economy. One consequence is that a Keynesian-type “coordination failure” appears inevitable, given enormous uncertainties facing both brown and green sectors, inadequate carbon markets, mercurial public policy (changing with every election), and an almost total lack of international coordination. To be more specific, this section outlines four reasons why we expect a disorderly transition, several of which were touched on in earlier sections. The messy handover is important because it implies periodic supply shortages, disorderly markets and bouts of elevated price volatility.

First, green energy investment is not ramping up nearly quickly enough. We’ve committed to leaving fossil fuels but haven’t invested sufficiently in their zero-carbon replacements. The world has dramatically reduced its investment in oil and gas production over the past seven years, largely because investors are skittish about long-term fossil-fuel demand in a decarbonizing world. Put slightly differently, the cost of capital is rising for oil and gas producers, as non-sovereign investors endeavour to reduce their exposure to fossil fuels. However, the growth of green energy has been frustratingly slow. Last year, the world put only $755 billion into the energy transition. This is huge by historical standards but, according to the IEA, is less than one-quarter of what is necessary by the end of the decade. The net result of the world not investing in zero-carbon energy fast enough is a major risk of energy supply shortages in coming years.

Second, according to the IEA, half the technologies needed to achieve NZE by 2050 don’t yet exist on a commercial basis. Wright’s Law will certainly help with this process, and renewable electricity is getting cheaper. But this just isn’t happening quickly enough. Moreover, government policy (including R&D, infrastructure investments, subsidies and carbon pricing) continues to be underwhelming.

“It takes seven years to get a permit for an onshore wind turbine in Europe, onshore not offshore.” - Daniel Yergin

Third, energy is a highly regulated industry, and our laws and regulations are enormously outdated. As Yergin emphasizes, this is a factor that unites renewable people and oil and gas people alike, they’re all extremely frustrated by the permitting process and regulatory roadblocks. There are thousands of stories about how long it takes to get things done in

the U.S., spending far too much time in courts and moving through one regulatory agency after another. Without a thorough streamlining and modernization of permitting and regulatory processes, the NZE timeline has little chance of being met.

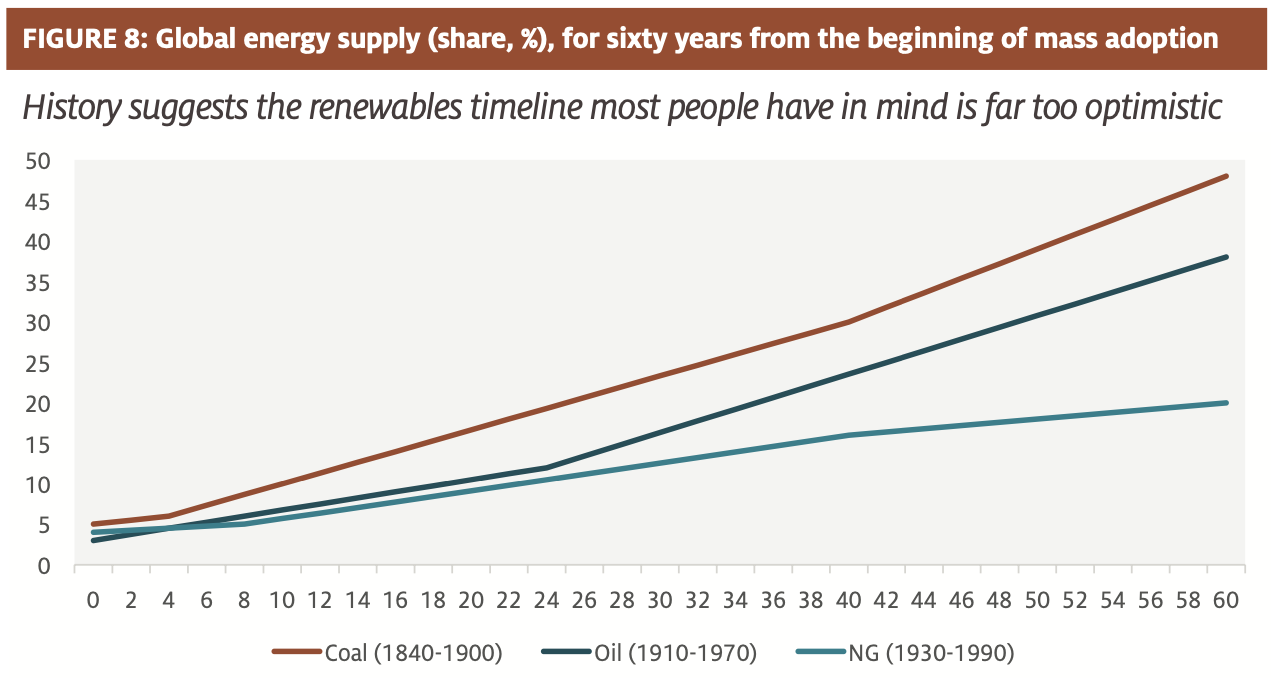

The final reason is that energy transitions always take a very long time (Figure 8). The energy industry is enormous and, in the physical world, improvements happen slowly (semiconductors, which improve according to Moore’s Law, are a notable outlier). Digital business models are built on bits and can rise to prominence in just a few years. Energy though lives in the world of atoms, where scale is built much more slowly.

Source: “Grand Transitions: How the Modern World Was Made,” Vaclav Smil, 2021 and “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need,” Bill Gates, 2021

As stressed by Bill Gates, after having read fourteen books by Vaclav Smil, “In the physical world, as Smil likes to tell us, things are very hard to change. It takes many decades to replace every cement plant in the world, every steel plant in the world.”

“We have done things like this before- -moving from relying on one energy source to another--and it has always taken decades upon decades.” - Bill Gates

The iron curtain comes down on energy: The Ukraine invasion as an accelerant for the transition

Moving on from our discussion of the messy handoff, the penultimate section of this paper represents a bit of a detour. However, it is a worthwhile one as the crisis with Russia makes it painfully clear that continued dependency on traded fossil fuels creates serious geopolitical vulnerabilities. The war in Ukraine has resulted in a renewed focus on energy security and a doubling down on the clean-energy transition. And while this is occurring globally, it is particularly acute in Europe.

Europe cuts short its holiday from history

With the advantage of hindsight, it seems almost unconscionable that the EU, over the last two decades, had actually increased its dependence on imported energy to 57.5% (this trend was especially pronounced in Germany, Netherlands, Greece and Poland). Moreover, the dependency ratio remains far too high in Italy (74%), Ireland (71%), Spain (68%), and others. Most regrettably, the EU’s biggest source of energy is Russia, which supplies 41% of imported natural gas, 27% of crude oil and 47% of coal.

“By mid-May we will come up with a proposal to phase out our dependency on Russian gas, oil and coal by 2027.” - Ursula von der Leyen, European Comission President (March 11 2022)

In response to Russia’s invasion, the EU recently announced the outlines of their new energy strategy, which envisages independence from Russian fossil fuels well before 2030—in part by finding new sources of gas, but also by tripling their renewable energy capacity. In the short-term, the EU aspires to reduce its purchases of Russian gas by two-thirds before the end of the year, largely by finding other sources, such as the U.S. Details regarding medium-term plans are still light, but France intends to construct six new nuclear power plants and is aiming for “total energy independence.” The posture of Germany has changed especially rapidly, with its finance minister, Christian Lindner, recently calling renewable energy “freedom energy.” Consequently, Germany has committed €200 billion to bring forward its goal of 100% renewable energy by more than a decade.

“(The U.S. wind and solar industries) emerged in the 1970s. And for the first 30 years, renewables were more about energy security than about climate. Climate really wasn’t an issue.” - Daniel Yergin

As Yergin has stressed for decades, climate investment has always been a matter of national security. Russia’s war on Ukraine has simply brought this back on our radar. The U.S. first learned this lesson during the energy shock of the 1970s and today is being reminded yet again. Green markets are much more local, but there still remain vulnerabilities, as Senator Manchin recently emphasized (“I don’t want to be standing in line waiting for a battery”). While decarbonization might be partially viewed as a national security policy, many of the metals, batteries and solar panels come from countries such as China, Russia and the Congo. This raises a host of vulnerabilities that need to be addressed immediately.

Implications for investors

“The 1974 oil shock resulted in the repricing of oil from $3.3 to $11.6/ barrel ... The 1974 shock was of the same order of magnitude as the one that is bound to be triggered by efforts to cut emissions in the decade ahead.” - Jean Pisani-Ferry

This article explained the four reasons why we expect higher inflation as a result of the transition to NZE. While inherently imprecise, we estimate these factors will increase trend inflation by 25 to 50 bps over the next decade. The confluence of greenflation plus the reflationary effect of deglobalization is likely to more than counterbalance the deflationary impact of tech. Consequently, inflation and nominal interest rates will probably be higher and more volatile, especially relative to the levels of the last two decades. This has not yet been priced into markets.

The reflationary impact of the green transition has profound implications for both policymakers and investors. For example, while the tech sector will likely continue to benefit from superior FCF generation, longer duration tech faces a headwind from higher discount rates. Overall, the sector composition of performance in the 2020s should prove quite different than it was last decade.

To identify investment opportunities, Epoch has always favored companies with effective capital allocation policies, including a demonstrated ability to deliver a ROIC above their WACC. We also look for companies with a record of generating FCF on a sustainable basis, and believe such companies are the most probable winners. This is true always and everywhere, including during the transition to the green economy.

Follow me for first access to my insights

I am the Managing Director & Portfolio Manager of Epoch’s Global Equity Shareholder Yield investment strategy. If you would like first access to my insights please hit the follow button.

4 topics

2 funds mentioned

John is a portfolio manager for Epoch’s Equity Shareholder Yield strategies. Prior to joining Epoch in 2012, John taught undergraduate economics as a lecturer at Fordham University. Before that he spent four years at HSBC Global Asset...

Expertise

John is a portfolio manager for Epoch’s Equity Shareholder Yield strategies. Prior to joining Epoch in 2012, John taught undergraduate economics as a lecturer at Fordham University. Before that he spent four years at HSBC Global Asset...