Gradually, then suddenly

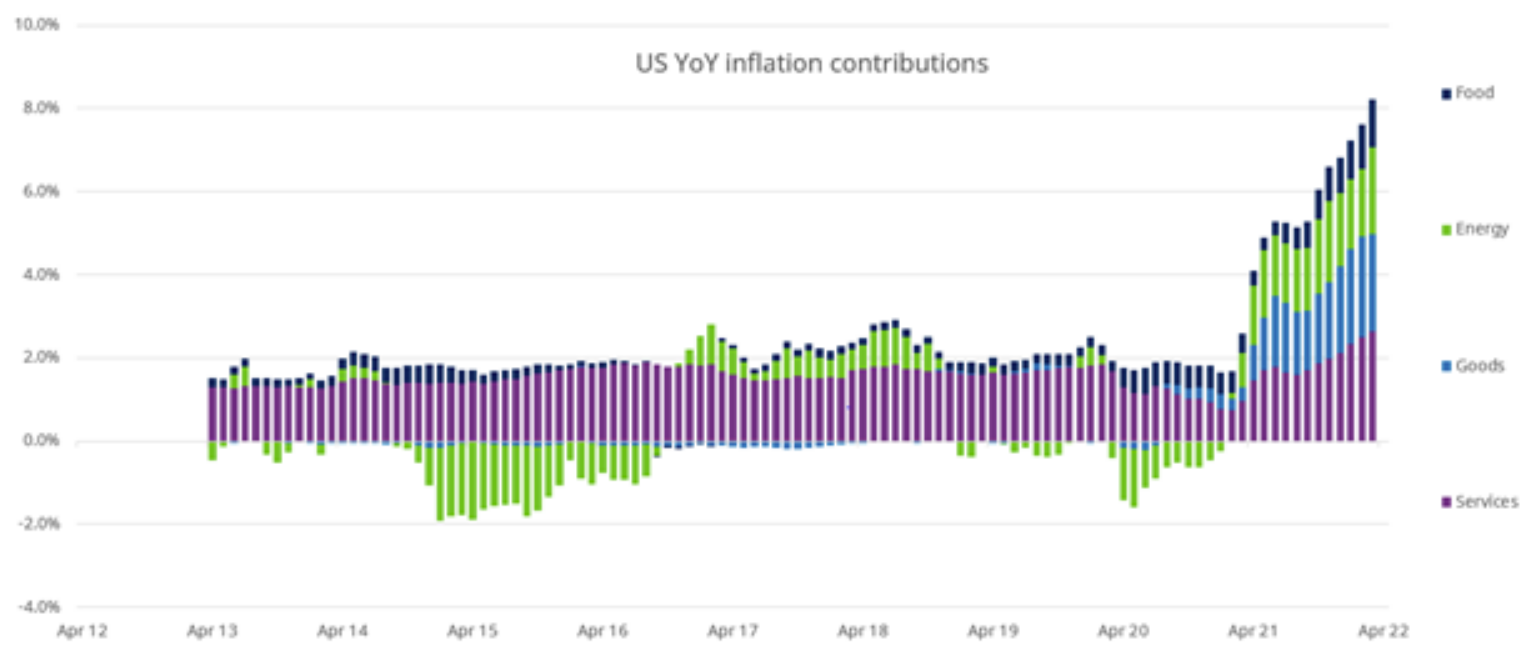

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually, then suddenly.” Hemingway’s famous line from The Sun Also Rises offers a few parallels to the changes we are seeing in global economies and markets at present. Many are expecting the current stressed market conditions – manifesting in skyrocketing European energy prices, stressed labour markets and increasing cross border tension – to revert quickly to the paradigm which has dominated markets over the past decade: easy money, low inflation, stable/rising profits and stable/rising asset prices. While this is a possible outcome, probable seems a stretch. We are all inclined to use recent history as the baseline for long-term forecasts, and the chart below on the composition of US inflation over the past decade explains why expectations see inflation reverting to the 2% mark once this ‘nuisance’ period of higher inflation passes. Unfortunately, there are other possibilities.

Source: Refinitiv, Datastream, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

As Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar recently put it in his excellent article ‘War and Industrial Policy’, “War means industry”. “Put simply…if there is trust, trade works. If trust is gone, it doesn’t”. The environment to which western economies have become accustomed is one of harmony. The passing of Mikhail Gorbachev should perhaps remind us that trust and harmony are won gradually over long periods. It can be eroded suddenly. Denuding domestic production capacity and criticising the behaviour of foreign governments, all while assuming ongoing provision of cheap goods and cheap energy to fuel economies centred upon consumption might be construed as a slightly optimistic long-run business model if one is seeking harmony. As time passes, they need you less and you need them more. Not the optimal bargaining position.

Source: Time Magazine - November, 1985 Time Magazine - June, 2022

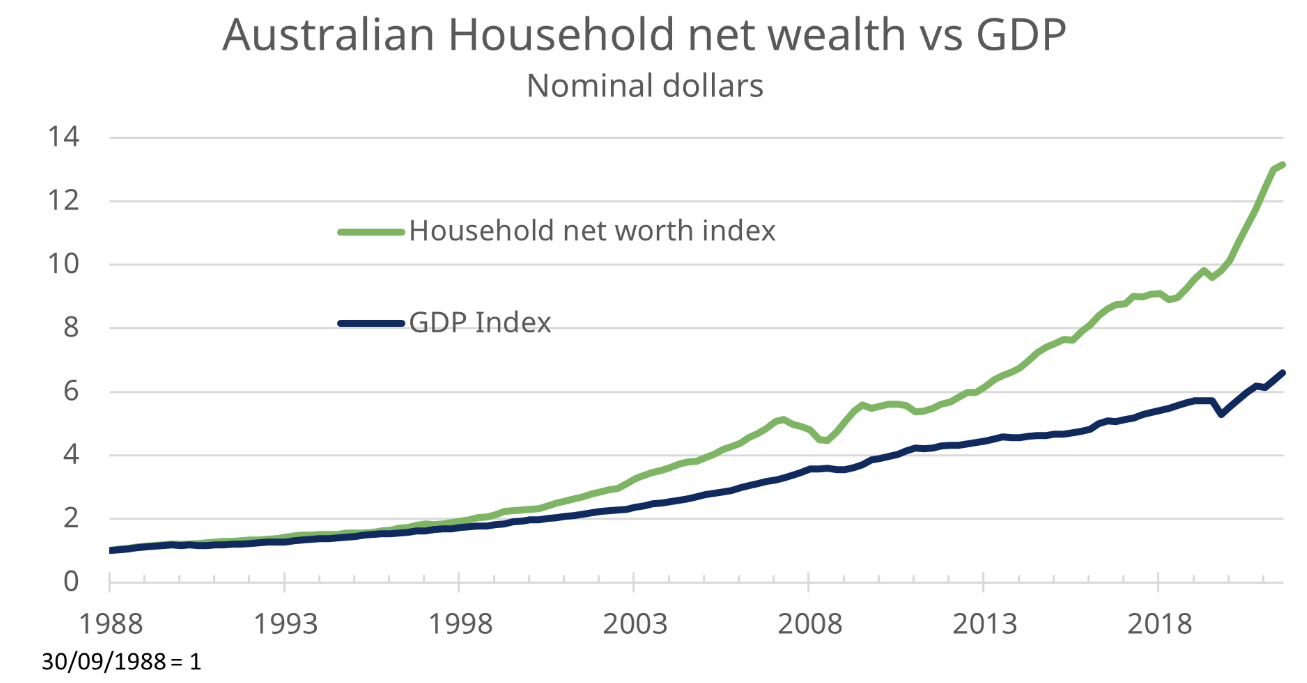

The financial system has paralleled this experience. The gradual erosion of integrity came to a head in 2008. Cardiac arrest was averted through shock therapy and has continued and grown ever since. The indirect consequences accumulate gradually, starkly evident in the separation between financial wealth and revenue (GDP) in the real economy. Some are obvious, such as growing wealth disparity and intergenerational inequity. Some are more subtle, such as diversion of resources and talent away from productive uses in science and engineering. The health of a business or an economy is often tricky to measure. It is always more important than short term results.

Rebuilding production

Courtesy of the conflict in Russia and Ukraine and associated sanctions, energy dependence has been thrust into the limelight. Europe is fragile. From lower renewable production than expected and Russian pipeline reliance, through to drought and lower water availability for nuclear, problems have tended to compound.

As the backbone of production, energy’s importance cannot be overstated. No energy, no productive capacity.

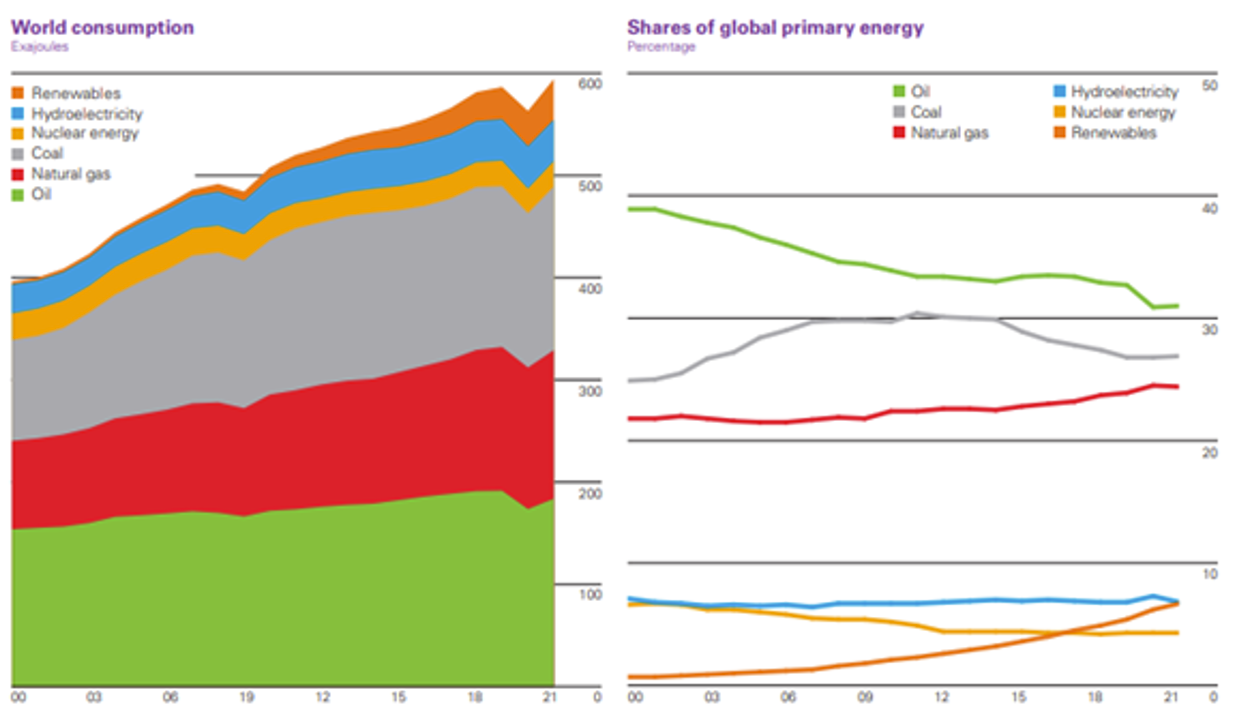

Assessing the health of the energy system is complex, however, it should be obvious that chains are only as strong as their weakest link. As evidenced in the chart below, we are some way off being able to rely on renewable energy. Physics and engineering capability limit the ability to add energy capacity exponentially, while a longstanding aversion to nuclear has eroded both capability and economies of scale, despite its obvious appeal as a zero-emission source of baseload (not intermittent) energy. We suspect the urgency of rebuilding an energy infrastructure capable of supporting a restoration of productive capacity will be an issue of dramatically escalating importance in coming years.

The fragility of the Australian energy infrastructure is also being exposed. The mismatch between an east coast market relying on ageing and deteriorating coal fired power and declining gas availability contrasts with the now prescient WA gas reservation policy, which sees both a well-supplied and low-cost domestic market and an increasing list of potential projects in areas such as fertiliser and battery materials added to an already healthy and low cost production base.

We are decades from transitioning to totally carbon free energy and failure to embrace gas as a vital step in the right direction in a very long run transition will be disastrous. As a contrarian, I’d hazard a guess the forecast revisions on population growth and prospects for Perth and WA may be a little brighter than anticipated relative to the east coast.

Source: BP Statistical Review

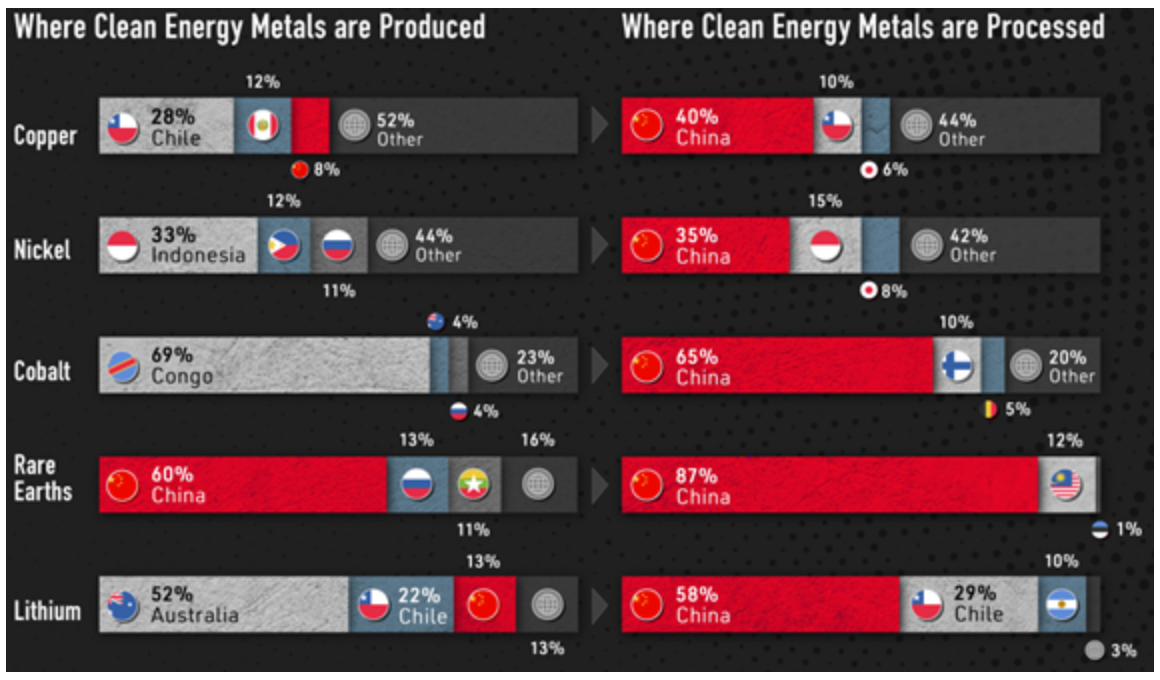

In the above light, the chart below on clean energy metals is both interesting and worrying. As is the case across a litany of consumer goods, computer chips and chemicals, China’s dominance in the production chain is concerning. As the US and western powers seek to restrain China’s dominance through constraining access to technology, the challenge to replicate China’s prowess and cost effectiveness in processing and scale manufacturing will be vast. Again, this is part of the reason we suspect inflation and disruption may be more pervasive and enduring than currently anticipated.

Source: Elements (Visual Capitalist)

This goes to the issue of commodity price volatility and the learned behaviour from cycles past. Higher interest rates in western economies are a response to higher inflation. Higher interest rates are expected to destroy demand and suppress inflation. However, as western economies produce little, consume a lot, and have become increasingly asset price and speculation driven, we suspect the assumed transmission mechanism may prove flawed. Prices of many commodities are unpredictable for good reason. Firstly, traded volumes in many areas represent a small fraction of global usage. Secondly, the levels of inventory held are usually modest. While critical, a long, harmonious period for global relations and trends towards ‘just in time’ inventory, has seen complacency develop on commodity availability. Lastly, capacity addition is usually tough and long dated. A bloated financial system will continue the pattern of transferring speculative wealth in commodities betting on short term price direction, however, only higher prices without government intervention to try and suppress them will create the investment incentive to fix the real problems.

Business health and results

As longer-term investors seeking to value businesses, we tend to see results season and the accompanying management meetings as incremental pieces in the puzzle of understanding and valuing a company rather than an opportunity to oscillate wildly between sadness and euphoria and punt our investor’s money accordingly. In any case, the dominance of quantitative investors in today’s equity markets leaves us struggling to understand the direction of most short-term price moves, let alone the quantum.

In this spirit, we’ve tried to highlight a few companies and issues that provided food for thought.

Like other marketplace businesses, we believe the value and long-term revenue potential of the ASX is linked to the health of the marketplace it operates.

Though measuring the health of marketplaces is controversial, we tend to believe a large and fragmented pool of buyers and sellers, an attractive value proposition for existing customers and optionality of attracting new assets for exchange on its marketplace are important attributes. Our assessment of the incremental health of equity markets over recent years has been roundly negative. Increased passive ‘free riders’ are eroding market pricing efficiency, reducing the number and quality of price setting in the market and justifying the move to privatise assets as misguided perceptions of volatility and risk overwhelm the obvious advantage of listed markets, which is readily available liquidity.

Directing spending to meeting the demands of high frequency traders providing no incremental capital to the market, eroding its health by extracting rent from retail investors and convincing gullible regulators and academics they are improving market efficiency through compressing spreads, is madness. The ability to extract high fees for speed of access reflects nothing other than the quantum of profits being extracted from retail investors. Most of these indicators continue to move in the wrong direction. Offsetting this, we believe the optionality in fixed income markets is significant. Controlling the custody of fixed income assets through Austraclear, we’d observe the ASX is uniquely positioned to offer governments the ability to issue debt directly to retail investors. An environment in which banks intermediate this market in return for offering investors inferior returns with greater risk makes no sense. Futures markets price fixed income securities because fractional ownership has not been properly enabled. Hopefully the future of the ASX will embrace more improvement of the marketplace and less distraction with high-cost technology fiascos. Given the relative efficiency and immaterial cost in clearing, settling and managing the custody of listed equities, attempting to adopt a blockchain solution to replace CHESS is a solution in search of a problem if ever there was one. Adding ever more cost in regulation and bureaucracy is a global corporate pandemic. We’ll let you know when we find the first problem comprehensively solved by additional regulation. Still waiting.

Supermarkets again left us in a quandary. Woolworths (ASX: WOW) is leading the supermarket world in terms of the quantum of capital spending in the business relative to sales, raising the question of how much a company should justifiably spend diluting returns in search of revenue growth, while the ‘ecosystem’ seems borne of consultant Venn diagrams rather than any commonsense.

Despite these distractions and shareholder wealth transfers to vendors in pointless acquisitions, it is difficult to find a more passionate and genuine CEO than Brad Banducci. In balancing the interests of tens of thousands of employees with those of shareholders, not resorting to price gouging to boost short-term profits and genuinely considering the long-term health of the business, we can offer nothing but praise.

While Coles (ASX: COL) saw weaker share price performance as the expectation of future revenue growth and market share gain overshadowed the superior record of Coles in turning reported profits into cash, we similarly find limited reason to criticise a path of less aggressive store rollout and ‘sticking to the knitting’. The necessity to try and force a winner and a loser may not always be the right question.

When it comes to assessing business health and building resilience, it is tough not to pick on Qantas (ASX: QAN) as one choosing to look after short-term shareholders rather than long-term business quality. Whilst acknowledging the vast challenges of managing an airline through the pandemic, recent history evidences a business which has decimated its workforce, aged its fleet and accepted some $2.7bn of taxpayer funding.

Despite the confidence drawn from a population desperate to travel and prepared to pay almost any price in pursuit of this goal, prioritising a stock buyback funded by taxpayer money whilst simultaneously destroying customer satisfaction sat rather uncomfortably with the building of long-term franchise value.

Fortunately, they can observe one of the other airlines vying for most delayed flights and lousy service by sticking their heads out the window.

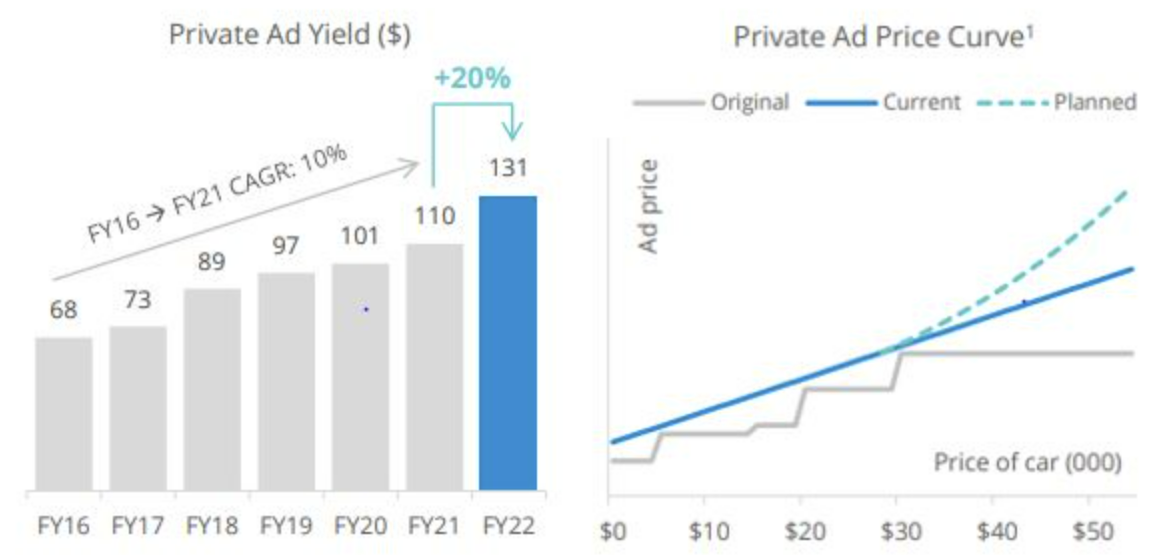

Lastly, we watch with interest the theme of ‘pricing for value’. Companies with unexercised pricing power hold an extremely valuable asset. The more it is exercised, the more this asset is extinguished and turned into the threat of future competition. Responding to an environment of income and wealth inequality, it is interesting how many companies are seeking to raise prices to those able to pay in seeking revenue growth. Unsurprisingly, as in the case of Carsales (ASX: CAR), most investors applaud it. Increased selling prices are a powerful aphrodisiac for equity investors. Ascertaining when differential pricing for undifferentiated product and service translates into imminent threat is never obvious.

Source: Carsales

Revenge of the asset owners

Perhaps one of the less obvious ramifications of increasing global tension and burgeoning inflation is the inflection point in pricing power for those with significant and difficult to replicate assets. Rising timber prices for pallets, rising construction costs for hospitals, chemical plants and buildings together with exploding costs around mine and energy developments are rapidly enhancing the future value of assets already in place. This trend is subtly attached to the trends observed earlier where past decades have seen offshoring and outsourcing of production erode the value and pricing power of local assets. Should the harmony to which we have become accustomed and priced into the distant future not transpire to be quite as smooth as planned, we feel asset owners may be decidedly better positioned than has been the case in recent years. Financing these assets in a manner which enhances their resilience will help further.

Market Outlook

The blind leading the blind

Those who have been awake recently have probably noticed a tendency towards unpredictability. Pandemics, labour shortages for which we still can’t reliably diagnose the cause (albeit not stopping the business community unanimously advocating a cure of more visas and immigration), voracious consumer spending and spiraling costs, all remain a feature of the environment.

While investors will always be keen for guidance such that they can avoid forecasting for themselves, professing much certainty in this environment smacks of overconfidence and hubris.

The number of share buybacks announced in recent times given this uncertain environment coincides with still elevated equity valuations. Increasing and uncertain debt costs is alarming. Far too many boards and management are managing their share prices rather than the company.

Stay real

The vast gap which has opened up between financial asset valuations and the revenues which support them dictate caution. To borrow from Dylan; “…the times they are a-changin”. Our preference is for companies which earn cash profits, reinvest them wisely and plan for shareholder returns to be delivered through sustainable dividends while managing their businesses with an eye to the more distant rather than near future. Market psyche remains one of investing in hot potatoes, where wildly elevated valuations versus history are justified in the hope of passing the potato. Like housing and most other assets, this psyche is borne of long experience. What has been learned gradually may change suddenly.

The gradual erosion of trust leaves the global economy far more exposed to conflict and price shocks. Investors and companies should be seeking to build resilience rather than waiting and hoping for a return to calmer times.

Learn more

For further insights from the team at Schroders Australia please visit our website.

4 stocks mentioned