How to value: Equities

Whether an investor holds equities directly as part of a core stock portfolio, or has broad exposure in the context of a multi-asset structure, knowing how to value what you own (or what you might want to own) is always a relevant skill set.

Of course, that’s a trite statement: thousands of professional investors and millions of retail investors spend time attempting to discern the value of asset prices, particularly a ubiquitous asset class like equities.

Rather than tread well-beaten ground in covering stock-picking methods, we’ll paint with a broad brush and outline what research identifies as some of the core building blocks to identifying total equity return – if you have an idea of what an investment will return to you, you have an idea of what you’ll pay for it.

The Fundamentals of Total Return

There are a few different methods that professional investors use to assess the total return of equities.

One option splits return out into more components to get granular detail:

Total Return = Revenue + Margin + Income* + Valuation*Where income itself involves dividends, placements and buybacks.

Yet another might take total return and look at the fundamental analysis that requires knowledge of both market dynamics and financial statement analysis:

Total Return = Starting Valuation + Market Expectations + Leverage

Both methods have their merit and implicitly acknowledge that there is uncertainty in any form of forecasting. To bring one final combination of building blocks into the fold, our preferred return composition for single equities involves:

Total Return = Dividend Yield + Earnings + Valuation + Currency**Currency is implicit in the other models, if relevant

Basic financial theory tells us that the price of any asset is the present value of future cashflows – meaning cash flows in the future are worth less today (because of the time value of money) and need to be ‘discounted’ back to today, giving us the present value of those cash flows – this model (known as the Discounted Cash Flow model, or DCF) takes that somewhat abstract statement and breaks it down into three basic fundamentals of any company’s value:

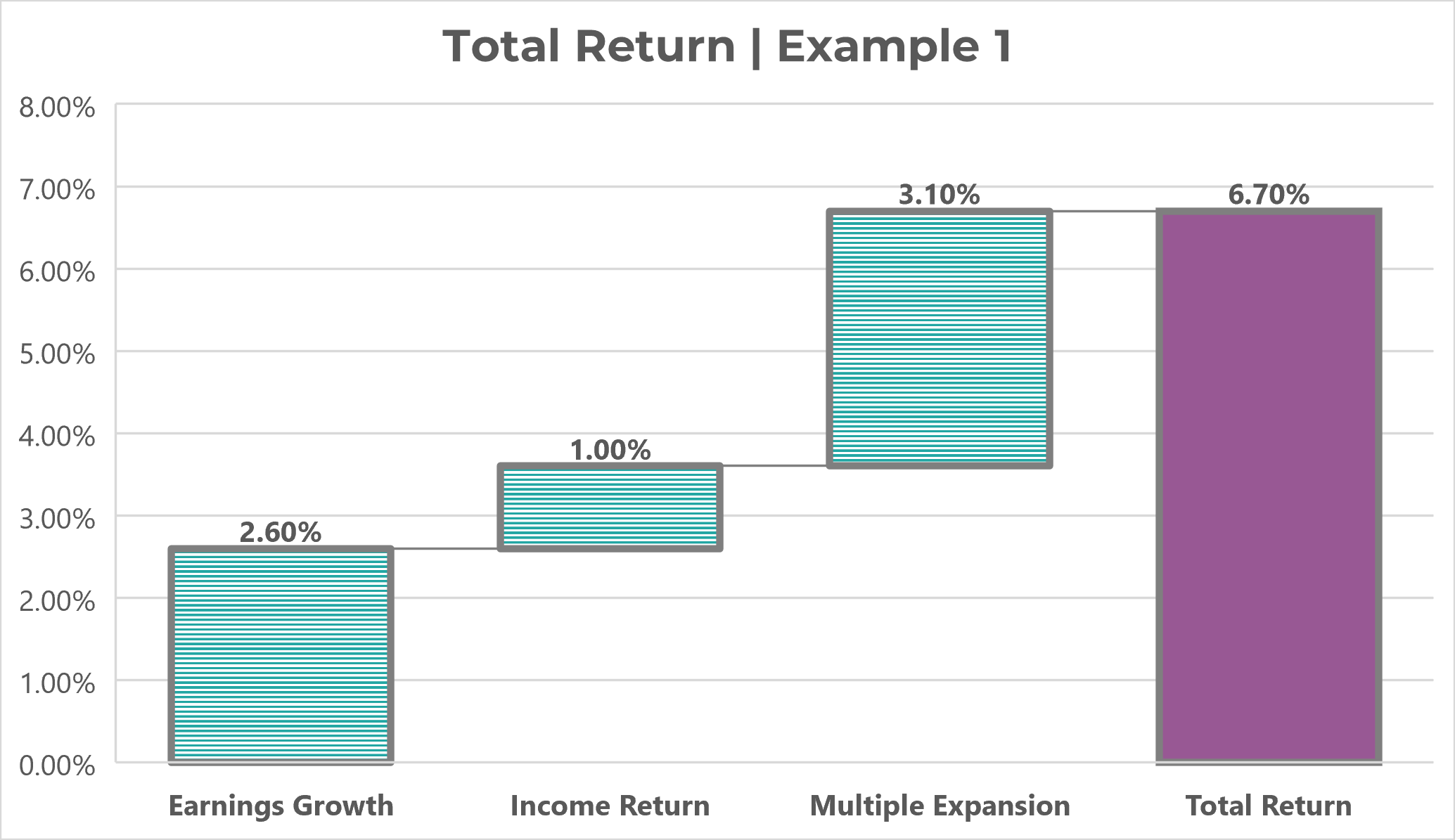

- Earnings Growth (Earnings Per Share, or EPS)

- Income Return (Dividends)

- Multiples (The price you’re prepared to pay for each dollar of those earnings, or Price/Earnings - P/E)

Earnings growth is a finicky subject to forecast, even full-time equity researchers can be off on their forecasts 3-6 months out, let alone a long-term investor attempting to identify potential EPS figures 3-5 years out.

One method is to use smoothed returns over long time horizons, taking historical earnings growth across at least one full business cycle to get a view of the trend.

Another is to simply substitute the national GDP figures of the firm: significant research has identified that for the majority of firms, over the long run their earnings trend towards the growth of the economy as a whole.

Income return is thankfully far less finicky to incorporate into a long-term view: companies are generally quite upfront and forward-looking with their dividend policies, and assuming that they can execute on said policies this should provide a solid foundation for assessing income returns.

The simplest way to consider this is to calculate the dividend yield of an equity:

Yield = Dividend (per share) / Market Price

An investor can also add complexity by accounting for potential buybacks, which are anti-dilutive and therefore act as ‘income’ increasing the proportion of future cashflows that existing investors receive.

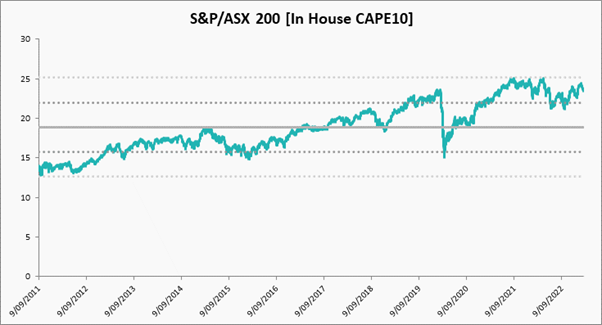

Finally, we have multiples – internally, our preferred method of viewing the multiple of market indexes is the Shiller P/E ratio, also known as the CAPE 10 (cyclically adjusted P/E) ratio. Simply, this ratio averages out the past 10 years of P/E to get a smoother profile which should control for the cyclicality in the earnings cycle.

Putting

this together, we can get a picture of how you might measure the total return

of an equity’s realised gains, or value the future earnings potential of an

equity security:

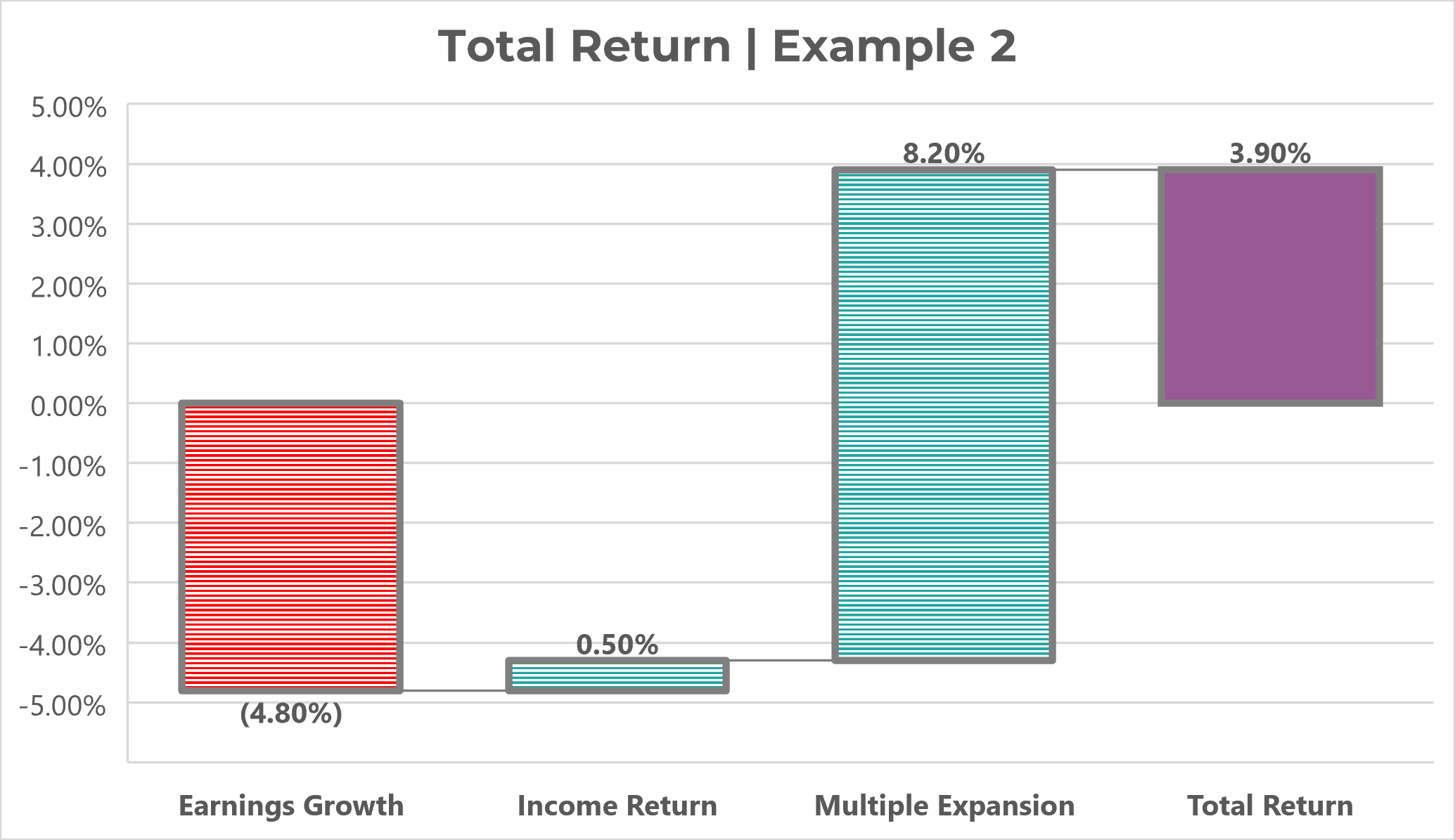

Or, if we want a more contemporary example of companies that had losses but grew in multiples throughout the bull market of 2021:

Paying Dividends

With these methods, many of the largest investment firms in the world inform their view of portfolio attribution, expected return and long-term forecasts for securities or even entire indexes.

There will always be uncertainty with forecasting, in fact, many fundamental investors will tell you there’s uncertainty in valuing a static company for its true intrinsic value – however with fundamental components like earnings, income and multiples, investors can form a more robust sense of how they might put a value on equities going forward.

Whilst we don't attempt to value individual stocks - where our greatest value to a total portfolio comes from deciding in which markets to be invested, and with how much - these methods remain relevant for understanding underlying assets. No method is ever perfect. But understanding where your returns come from and getting the balance right will allow investors to both compound wealth over time and manage risk throughout the process.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

You can follow my profile to stay up to date with other wires as they're published – don't forget to give them a “like”.

3 topics