How to value stocks

It’s the stock valuation special!

In this episode of What’s Not Priced In, Greg Canavan and I tackle one of the biggest questions of them all: What is a stock worth? And how do you value it?

Using three examples, Commonwealth Bank [ASX:CBA], Telstra [ASX:TLS], and Apple [NASDAQ:AAPL], we covered the following:

- Why bother with valuation methods at all?

- The advantages of Greg’s Return on Equity (ROE) valuation approach

- Why this method?

- Dividend discount valuation approach versus the ROE approach

- The limits and shortcomings of the ROE method

- The importance of conducting DuPont analysis to break down the sources of ROE

- Why valuation is more art than science

Enjoy the episode, it was packed with great information!

-MYB4yCsjNKiN

Why care about a stock’s value?

Investing in its most basic sense is buying businesses for less than what you think they are worth.

We don’t invest in stocks we expect to tank.

But to buy businesses for less than what we think they’re worth, we must come up with a value for those businesses.

As investor Brian McNiven wrote in his Concise Guide to Value Investing: How to Buy Wonderful Companies at a Fair Price:

‘Although the objective of all investors is to seek superior returns with minimal risk by acquiring stocks in wonderful businesses at a price that represents good value, if they do not know how to calculate value, the objective is achieved by chance, rather than design.’

But how do you determine the true value of a company?

Stock valuation — the science

Off the bat, Greg began the episode with a bit of a downer. There is no right way to value stocks and no such thing as true intrinsic value.

But there is approximation.

Investing is a blend of art and science. And the science lies with Return on Equity (ROE), Greg’s preferred approach to valuation.

His approach has three key inputs:

- Return on equity (obviously)

- Required rate of return (also known as the discount rate; influenced by the prevailing risk-free rate and the chosen equity risk premium)

- Dividend payout ratio (how much profit is the company reinvesting versus doling out to shareholders?)

We can begin with a simplified case (adapted from Greg’s book You, Your Brain, & the Stock Market).

Valuation in a simple world

Imagine a business that exists in a world without stock markets, where only equity capital is involved.

And let’s assume this business runs on equity capital of $10 million. With the equity capital, it generates $2 million per year in net profit. In other words, the return on equity is 20%.

The business has generated this return for more than 10 years. But the person who owns it is getting old and wants to sell. How much should they sell it for?

Since this is the simplified case, let’s assume this business pays out all earnings as dividends and the owner’s required rate of return is 8%.

Given that the business generates a return on equity of 20% and the required rate of return is 8%, the intrinsic value of this business is $25 million.

How?

If you divide the 20% return on equity by the 8% required return, you get 2.5.

What that means is that for the business owner to earn their ‘required return’ of 8%, on a business generating a 20% return on its equity capital of $10 million, they would pay no more than 2.5 times the equity value of the business.

In this example, 2.5 times the equity value is 2.5 times $10 million, or $25 million.

If the business owner (or purchaser) is dubious about this price tag, they can simply look at the net profit from the business ($2 million), divide it by the proposed purchase price ($25 million), and they’ll come up with 8%. And the deal is done.

(Relatedly, you can divide the $2 million net profit by 8% to get the $25 million).

Stock valuation the harder way

But most stocks don’t pay out all their earnings in dividends. Many retain earnings and reinvest to expand.

A business reinvesting all its profits is a much more valuable business than the one paying out all profits as dividends, provided it can maintain the rate of return on reinvested capital.

Can the ROE stock valuation method account for that?

It can, but it involves more maths. Not too much, though.

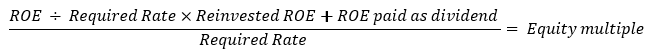

The amended way to account for reinvested profits is based on Brian McNiven’s valuation formula found in his earlier-mentioned book.

Here it is in all its glory:

What does this gibberish mean? The formula looks busy … but its appearance belies its simplicity. A worked example will help.

Let’s use the previous example but now assume the business’s payout ratio is 50%.

That means that on an ROE of 20%, the reinvested ROE is 0.50*0.20 = 0.1.

So here’s how the formula will look, deconstructed:

(0.2/0.08 x 0.1 + 0.1)/0.08 = 4.375

Let’s walk through it slowly…

0.2/0.08 = 2.5

2.5 x 0.1 = 0.25

0.25 + 0.1 = 0.35 or 35%.

In effect, what this means is that after compounding 50% of profits through reinvestment, the original 20% ROE is ‘boosted’ to 35%.

0.35/0.8 = 4.375

The intrinsic value of our company, then, is 4.375 times its equity, or book, value. In our example, that’s 4.375 times $10 million, or $43.75 million.

That’s up considerably from the $25 million intrinsic value the company had when it paid out all earnings as dividends.

For regular stocks, you’d multiply the equity multiple by a stock’s book value per share to get an estimate of intrinsic value.

So that’s the formula.

I can write more, but I shouldn’t. This piece is meant to complement the episode, not supplant it!

Greg put a lot of work into elucidating his method, so it’s best to watch the episode for the full details.

He explains the ins and outs of the formula along with its logic and then puts it to use on CommBank, Telstra, and Apple.

During the episode, I also surprised Greg by running a dividend discount model on the stocks to see if our valuations differed.

Spoiler: they were very close.

Now, if you want more detail, you can check out Greg’s book I plugged earlier.

He dedicates a few chapters to the ROE valuation method.

You can also check out Brian McNiven’s book, Concise Guide to Value Investing.

Greg came across this book in the mid-2000s and bases his valuation approach on McNiven’s.

McNiven, in turn, came up with his valuation model to mimic Warren Buffett’s.

Stock valuation — the art

The pesky thing with stock valuation is that it’s not as scientific as, say, calculating the velocity of a projectile.

An investor may strive for the physicist’s precision but never attain the physicist’s accuracy.

A few quotes bubble to the surface. First, John Maynard Keynes:

‘It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.’

And then Benjamin Graham:

‘Mathematics is ordinarily considered as producing precise and dependable results; but in the stock market the more elaborate and abstruse the mathematics the more uncertain and speculative are the conclusions we draw therefrom. In 44 years of Wall Street experience and study, I have never seen dependable calculations made about common stock values, or related investment policies, that went beyond simple arithmetic or the most elementary algebra. Whenever calculus is brought in, or higher algebra, you could take it as a warning signal that the operator was trying to substitute theory for experience.’

A valuation formula can easily lead to precise error, especially if the formula is swarming with Greek letters.

But as Greg said, his valuation methodology is quite simple and all you really need.

As he writes in his book:

‘If the inputs are logical and accurate, you can value a business using high school maths. When it comes to the stock market, simple is effective.

‘So don’t underestimate [the approach] on account of its simplicity. Warren Buffett uses this methodology to run Berkshire Hathaway, and he’s done pretty well out of it.’

In the end, having a systematic way to value a company is crucial for a serious investor.

But it’s not enough to memorise a few valuation formulas and superficially apply them from one stock to the next.

Your valuation model is only as good as your assumptions.

And that’s where the art comes in.

Enjoy the episode!

3 topics

3 stocks mentioned

1 contributor mentioned

.png)

.png)