Inflation: an investor’s friend and foe

The data is showing it, central bankers are focusing on it and the community are feeling it at the fuel pump, the food aisle and through friendly conversations at the café. After more than two decades of ‘nothing to see here’, inflation appears well and truly set for a comeback. With ultra-low interest rates soon to be a thing of the past, how should companies and investors alike pivot their thinking around investment decisions to factor higher inflation? And amongst the doom of higher prices, are there reasons to be more positive about the prospect of inflation in equity markets?

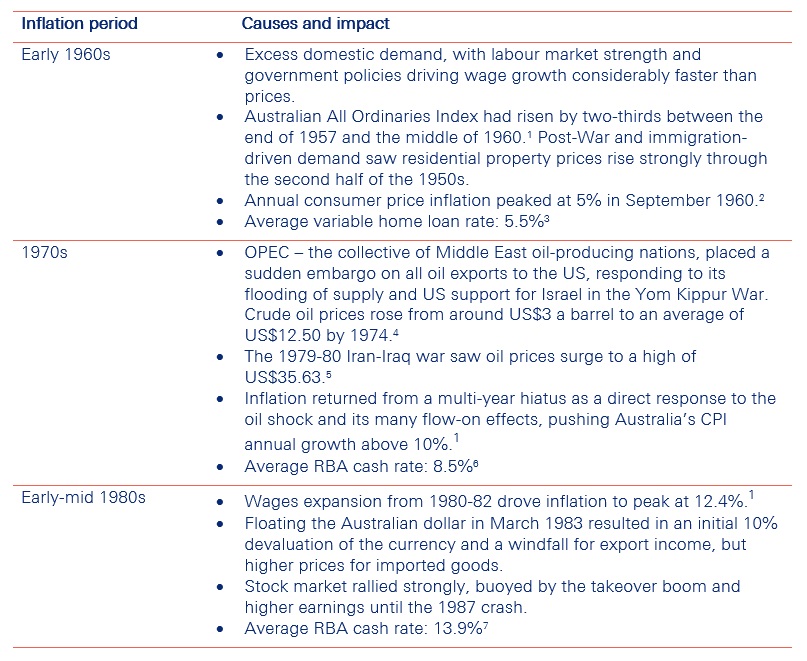

From the earliest days of high school economics classes, we were drilled on the history of inflation, why it exists and the devastating economic impact it can have if not kept in check. We were lessoned on the inflation shocks of the 1960s, 70s and 80s and their economic impacts. We were enlightened on the flow-on impacts of variables like oil prices, currencies and the intersection with geopolitical factors.

But one clearly contrasted factor in the current environment compared with prior periods is the unprecedented situation where the major economies are flush with essentially free money. Central bankers are now tackling questions on how to unwind the excesses before inflation affirms its path. No doubt they are re-examining inflation’s lessons of the past.

- Stevens, G. “Inflation and Disinflation in Australia: 1950–91”, October 1992

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Consumer Price Index (All Groups)

- Orange Mortgage & Finance Brokers, “Historical Home Loan Interest Rates Australia”

- Amadeo, K, “Oil Price History—Highs and Lows Since 1970”, March 2022

- Amadeo, K, “Oil Price History—Highs and Lows Since 1970”, March 2022

- Reserve Bank of Australia, Interbank Overnight Cash Rate – monthly average over the period

- Reserve Bank of Australia, Interbank Overnight Cash Rate – monthly average over the period

Many academics and policy makers have laboured extensively to understand inflation’s many drivers to predict its future trajectory. Esteemed Economist, Milton Freedman, was one of those who, after dedicating much of his waking hours to research, dismissively came to the view that “inflation is, always and everywhere, a phenomenon”.

Considering the early signs of inflation—both domestically and offshore—it is clear the RBA will follow through with higher interest rates. The timing of the first move and extent of the hikes is still the subject of speculation, but the RBA Board will be acutely aware of the need to address inflation while also considering the potential impact on the Australian dollar. The latter presents a delicate balance, as a stronger Aussie dollar lowers the cost of imported consumer goods like apparel, machinery and cars but weighs on our nation’s export competitiveness.

Inflation and the bottom line

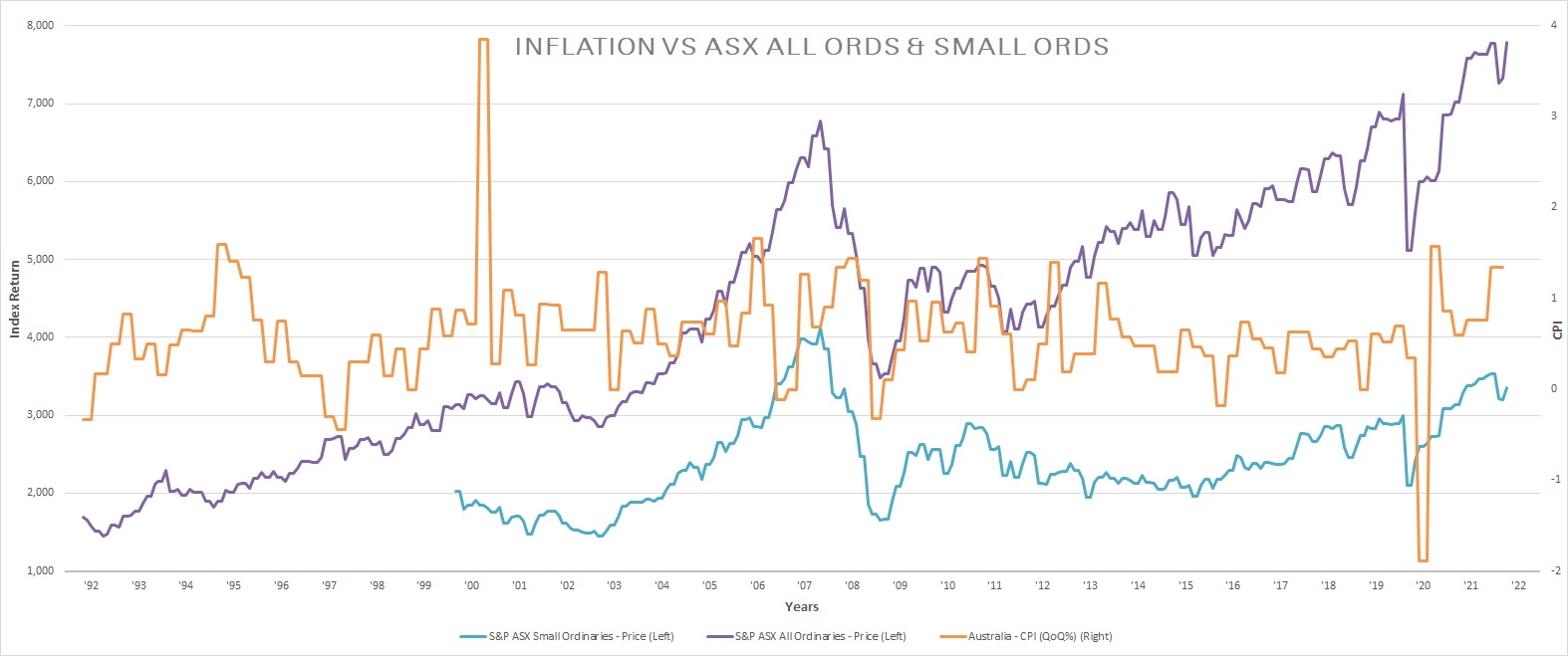

Inflation case studies and their evolution provide for interesting historical perspectives, but of greater interest to investors is how inflation impacts equity market returns. Unfortunately, when looking at the Australian equity market and inflation over the last 30 years, correlation between the two is inconclusive. There are three key events, mainly market drawdowns, which is worth examining:

- Tech wreck – Leading into the tech wreck of 2001/2001, inflation did spike, which was followed by a drawdown in equity markets, with the S&P/ASX Small Ordinaries reacting earlier than S&P ASX All Ordinaries.

- Global Financial Crisis – Heading into the financial meltdown, inflation fell away quite considerably however equity markets continued to all-time highs with inflation recovering just in time for one of the worst market falls in history. Subsequently inflation falls a second time in a matter for a few years bottoming along with equity markets.

- Covid Pandemic – A different story again, with inflation turning negative but only after dramatic falls in equity markets as Covid-19 grinded the global economies to a halt. Inflation severely declined, as lockdowns were enforced, however, this was short lived as supply chain issues and large discretionary spending drove inflation higher.

Source: Factset

Whilst we cannot correctly predict macro movements, at NAOS what matters more to us is the impact on each company’s long-term earnings prospects. Inflation makes its presence felt differently across industries and many listed companies are currently facing higher input costs associated with raw materials, transport, labour shortages and other knock-on effects which can flow through to underlying earnings. The feedback we have received tells us that these impacts vary significantly between companies and industries. The key for investors is to understand the underlying valuation drivers and how each business model is adapting. Companies that generally fare better in this regard are those which are either ahead of the curve in adjusting pricing strategies or are in a more price-resilient space with the ability to pass-through higher costs to customers.

An example of this is a company like Big River Industries (ASX: BRI), a building supplies & distribution business with a focus specialist focus towards timber products. In an inflationary environment they have the ability to pass through cost pressures with pricing increases. Add that to a significant backlog of construction demand and supply shortages, Big River Industries is benefitting from a strong demand cycle, which helps to further reinforce the price resiliency of their operations.

If we compare this to say an airline, yes they stand to benefit from the rebound in travel but offsetting this arguably one-off mean reversion, inflation will see airlines experience materially higher input costs in the form of fuel prices which may prove difficult to fully offset when you consider the airline industry has historically been fiercely competitive and ticket prices have experienced deflation over time. Staffing shortages & geared balance sheets may stand to further exacerbate the issue.

Part of our investment process includes industry analysis, whereby the NAOS team delve into pricing dynamics and product demand potential through engagements with company management. These qualitative insights can also shape our valuation assessments.

“We are seeing probably the biggest price inflation shift that I’ve ever seen in my career coming through. We’d be out of business really quickly if we didn’t pass these prices on because they’re just so significant” Robert Giles, CEO, SPC Australia

Translating the impact to equity valuations

Most equity valuation techniques like price-earnings ratios, discounted cash flows, cost of capital or terminal value, implicitly take account of inflation. Earnings and cash flow analysis makes an assessment of future product prices and demand to assess potential sales volumes, while cost of capital measures invariably incorporate an assumed market risk-based return and risk-free rate, i.e., a close proxy to the RBA cash rate which reflects future inflation expectations.

Over the past decade where inflation has not been a major factor and the cheap money paradigm has been at play, stock relative valuations have tended to narrow in dispersion. If we now look forward and add back the constraint of a normalised risk-free rate and the prevalence of inflation, we expect to see a much greater spread across company valuations.

Regardless of valuation approaches and inflation impacts, many more fundamental factors warrant consideration when assessing value. At NAOS we consider valuations under the lens of a company’s long-term earnings potential, with a firm eye on its management quality, their alignment to success or otherwise, and the industry dynamics in which they operate. By nature, this approach also leads us towards the small-to-medium end of the market spectrum where, in our experience investors can access more singularly-focused companies and where management strategy can exert a more direct influence.

Assessing the value of inflation

The re-emergence of inflation will likely present additional influences on a company’s value, which can be nuanced at the industry level. Our thoughts on how rising prices will influence some of the major market segments are outlined below.

Financials: Higher interest rates induced by inflation can present mixed scenarios for banks and insurers. In one sense, higher interest rates provide scope for banks to increase their net interest margins – the difference between their wholesale borrowing rate and the interest rate they charge customers. All else being equal, higher margins equals higher fees, so long as it’s supported by a strengthening economy and the level of bad debts are contained. For insurers, inflation can strengthen earnings as they tend to hold significant cash in reserves. Higher interest rates drive higher yields on their investments. But financials are volume-focused businesses and at risk if inflation drives lending or premium rates down. This was evident in the 1990s when the RBA cash rate peaked at 17.5% and credit losses totalled around 8.5% of banks’ lending volumes. (Rodgers, D. “Credit Losses at Australian Banks: 1980–2013”, June 2015)

Listed real estate: Property yields tend to have a close alignment with inflation, albeit with a material lag owing to the long-term nature of leases. Commercial leases in particular tend to have multi-year tenures and pre-set review periods to provide an opportunity to lift rents. It is often at this point where rent reviews take inflation into account.

Retailers: Companies like Woolworths, Coles and Metcash operate in highly competitive markets and are subject to a range of inflation sources. Like other sectors, they seek to pass-through higher costs to customers but also face risks that consumers will respond by changing their preferences, particularly when it comes to more discretionary items.

Technology-based growth stocks: Within the Australian market, stocks in this cohort tend to exhibit a higher degree of resilience to inflation. They benefit from so called network effects, whereby they can harness the power of their distribution reach to customers without incurring significant additional costs. A stock like Xero Ltd, which holds a dominant position in the business and accounting software industry, generally has limited sensitivity to inflation, as its accounting platform tends to be regarded as a fixed cost of running a small-to-medium sized business. Xero’s revenue risk is mainly connected with the loss of customers whose business can’t compete in an inflationary environment.

Industrials: Generally speaking, industrial company shares are arguably better placed than other asset classes in terms of their ability to capture and even capitalise on higher inflation. Many industrial companies price their goods and services to reflect prevailing market demand and supply dynamics, and typically aim to pass through higher input costs to customers. Furthermore, strong businesses can potentially capture demand-pull inflation (price responses from stronger demand for their goods and services) resulting from a growing economy, more money in the system from fiscal or monetary stimulus, demand expectations and currency fluctuations, to name a few.

As long-term investors, we spend considerable time speaking with management teams to understand their business models, product markets and how they are adapting to current and emerging factors like inflation. Ultimately, the companies we find most compelling are those with the ability to generate consistent cashflow growth and maintain or grow operating margins to deliver a sustainable yield, regardless of inflation settings through time.

In our view, inflation is neither friend nor foe, but a synergistic factor that captures both risk identification and return enhancement opportunities, among other fundamental factors of success. Ultimately, for us at NAOS it comes down to the strength of conviction in a small collection of companies founded upon resilient business models that should find their place in a portfolio. As famed investor, Warren Buffett says, "A lot of great fortunes in the world have been made by owning a single wonderful business. If you understand the business, you don't need to own very many of them.”

5 topics