Is Australia becoming the Mediocre Country?

Australia has dined out on being the ‘lucky country’ and being recession proof (ex-COVID) and with that comes a sense of both complacency and entitlement. Reading the daily press and observing this most recent reporting season provides ample evidence.

It is becoming abundantly clear that the Australian economy is in the midst of a multi-year grind:

- GDP growth is running at ~1.5% (y/y) and has been negative on a per capita basis for almost two years (the ‘luck’ might be running out).

- The post-COVID economic rally has fizzled as consumers drained the $200b+ of forced savings (courtesy of lockdowns), China re-opened to what is a ‘new normal’, immigration has been curtailed and tourism/foreign students returned to more sustainable levels.

- Employment growth is both modest and 75% of it is linked to debt funded government expenditure.

- The consumer is overwhelmed by cost-of-living pressures. And while it is yet to cause mass distress, high interest rates and energy/food/insurance inflation is definitely crowding out other parts of the economy (noting the consumer is >50% of GDP).

The mediocre economic reality is also mirrored on the ASX. Notwithstanding a solid rally in 2024 (ASX 200 +11.4%) in anticipation of better times, the February’s earnings season was simply ‘mediocre’. In our view:

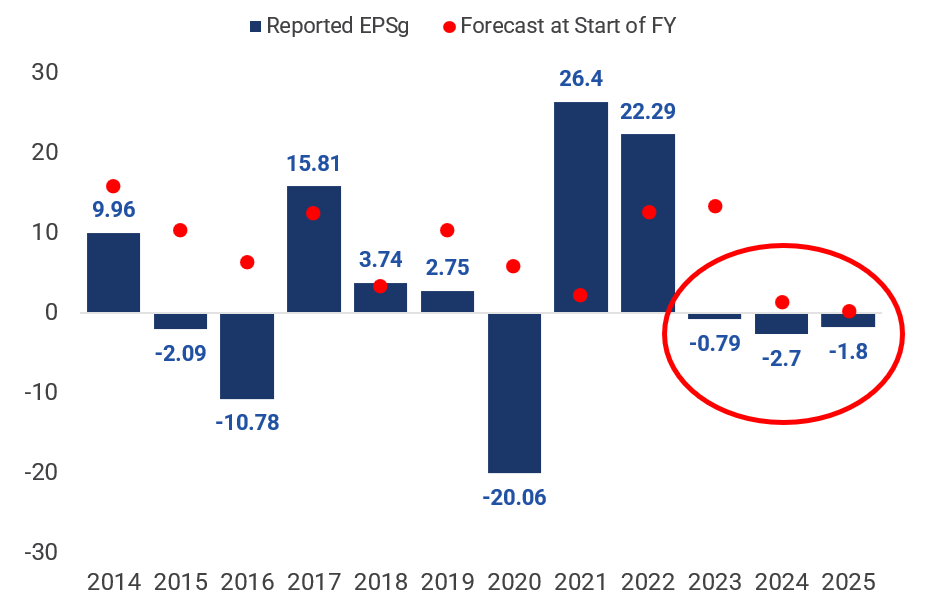

- F25 is likely to mark the third consecutive year where ASX 200 aggregate earnings decline (refer Chart 1).

- Margin pressure is apparent across most sectors. It’s now rare to find a company with positive jaws (revenue growth > cost growth), which is consistent with Ai Group’s analysis that demonstrates margins in 2024 were experiencing their steepest decline since the data commenced in 2001(1).

- Almost half the ASX 200 is ‘ex growth’, notably the banking sector (23.9% of ASX 200 market capitalisation) where earnings were higher in 2017 (almost a lost decade), the resources sector (16.7%) where commodity prices have drifted down while costs stepped up, and REITs (6.7%) which are contending with weak rental trends and higher funding costs and incentives.

Chart 1: Australian companies – Reported EPSg vs initial forecast (%YoY)

Source: Goldman Sachs.

A series of policy and economic ‘own goals’ have undermined investment and growth:

- Energy – Australia has abundant oil and gas resources, but due to regulatory bottlenecks we now have a gas shortage and surging prices. The idiocy of being both one of the world’s largest LNG exporters but now building LNG import terminals (given the shortage) is completely beyond belief.

- Productivity and Industrial Relations – these remain the Achilles heel of the economy and over time will undoubtedly erode our competitiveness and living standards.

- Bureaucracy, red tape and green tape – there are countless examples, but a few recent highlights include:

- 49% of the value of a house and land package in Australia is now taken up by taxes/regulatory and infrastructure charges(2) and it’s a staggering 106% higher since 2019.

- The NBN – a tax funded asset (or liability?) – just spent $750m to upgrade the network and has added 100 subscribers (it would have been cheaper to give them a new home rather than a modem).

- Government largess and taxes – Australia is amongst the highest corporate tax collectors in the developed world and total taxes as a percentage of GDP are now at a record high. It’s a clear handbrake on both investment and prosperity.

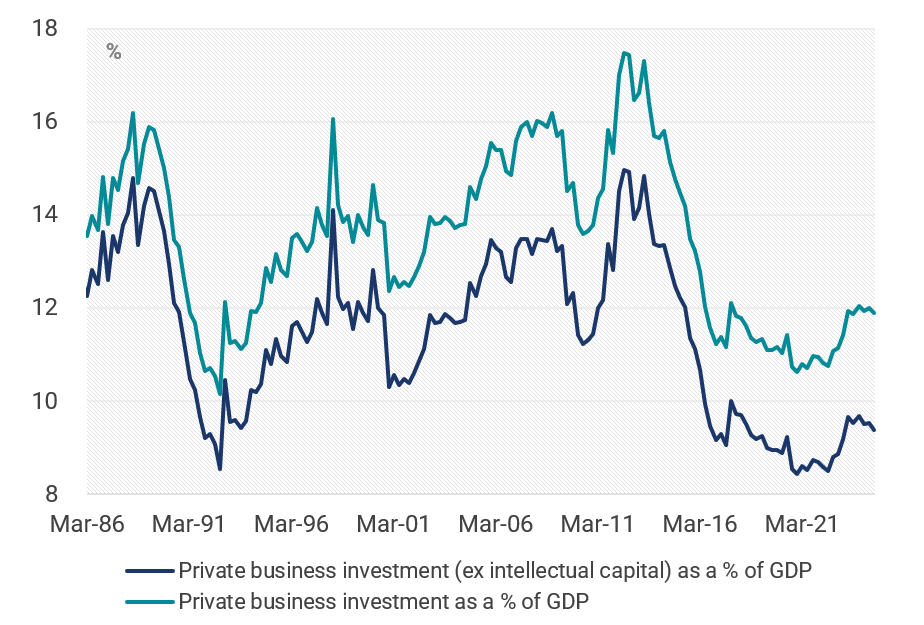

All of this results in weak confidence (business and consumer), an investment drought (refer Chart 2), risk aversion and tendency to reluctantly accept it. If you are wondering what happens if this persists, come visit Victoria!

Chart 2: Private business investment share of GDP down 30-40% since 2012

Source: ABS, YarraCM.

This risk aversion and lack of investment becomes self-fulfilling and it perpetuates the ASX 200’s lack of earnings growth (at an aggregate level, some companies are prospering). To the extent we hear about companies investing heavily it tends to be outside of Australia – take the hint Canberra, capital is mobile. We note with interest that Woodside and Orica are investing heavily in the US, Rio Tinto and BHP in Latin America and easier places to do business such as Mongolia.

Breaking out of this cycle requires vision, courage and execution. The examples are few and far between in corporate Australia, but they are there. Origin Energy’s (ASX: ORG) contrarian investment in Octopus Energy is one brave and successful example, as was Bluescope’s (ASX: BSL) investment to expand US steel capacity over the last five years. It is apparent to us in our engagements with companies that Boards and CEOs often appear overwhelmed with ASX listing guidelines, proxy advisers, ESG reporting, and peer and reputational risk. Like most investors, we would welcome a renewed focus on generating strong long-term shareholder returns.

At Yarra we are actively seeking ambitious companies that intelligently pursue growth rather than simply harvesting dividends and flying below the radar. Given the macro malaise we describe, our best ideas currently either have large offshore business interests or can benefit from micro trends and self-help. Recent additions and high conviction positions in our portfolios include Treasury Wine Estates (ASX: TWE), Woodside (ASX: WDS) and APA (ASX: APA).

Access companies offering strong growth potential

The Yarra Ex-20 Australian Equities Fund offers exposure to forward-looking companies by investing in a portfolio of stocks that sit outside the S&P/ASX 20, offering greater diversity, superior returns and strong growth potential over the medium to long term.

5 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned